For Lack of Wanting: Discourses of Desire in Ukrainian Opiate Substitution Therapy Programs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LINKING INFECTIOUS and NARCOLOGY CARE) Evidence-Based for Engagement in HIV Care

COMPENDIUM OF EVIDENCE-BASED INTERVENTIONS AND BEST PRACTICES FOR HIV PREVENTION LINC (LINKING INFECTIOUS AND NARCOLOGY CARE) Evidence-Based for Engagement in HIV Care INTERVENTION DESCRIPTION Goal of Intervention • Improve engagement in HIV care • Improve retention in HIV care • Improve CD4+ cell count • Reduce self-reported hospitalizations Target Population • HIV-positive injecting drug users in treatment Brief Description LINC (Linking Infectious and Narcology Care) is an individual-level, strengths-based case management intervention for HIV-positive persons who inject drugs (PWID). It is adapted from the Antiretroviral Treatment Access Study (ARTAS). LINC involves coordination between the HIV and narcology systems of care to reduce barriers to HIV care and help motivate HIV-positive PWID to engage in care by supporting recognition of one’s strengths to make positive life changes. The initial session is delivered in a narcology hospital (e.g., in-patient addiction treatment setting) and includes provision of CD4 test results to increase engagement in HIV medical care. After discharge, subsequent sessions are conducted in community or clinic locations over six months. LINC aims to build self-efficacy, enable self-management, and increase outcome expectancies regarding engaging in HIV care via education and social support. Theoretical Basis • Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) • Psychological Empowerment Theory (PET) Intervention Duration • Five sessions delivered over six months Intervention Settings • Narcology hospital • Community or clinic locations • Phone Deliverer • Peer case managers (i.e., HIV-infected men and women in recovery from addiction) LRC Chapter – LINC (Linking Infectious and Narcology Care) Last updated March 17, 2020 COMPENDIUM OF EVIDENCE-BASED INTERVENTIONS AND BEST PRACTICES FOR HIV PREVENTION Delivery Methods • Case management • Printed materials • Discussion • Video • Goal setting Structural Components There are no reported structural components reported for this study. -

Boletin De Documentación Nº 37, Marzo De 2009

Su elaboración en formato electrónico, iniciada en julio de 2002, ha supuesto importantes ventajas de cara a ampliar y agilizar su difusión entre los profesionales del sector, permitiendo asimismo la localización de documentación relevante por parte de cualquier ciudadano interesado en el campo de las drogodependencias. Como en los números anteriores, en el boletín de marzo se recogen las principales novedades bibliográficas que, sobre los distintos aspectos relacionados con las adicciones, han tenido entrada en el Centro de Documentación e Información de la Delegación del Gobierno para el Plan Nacional sobre Drogas en los tres últimos meses. El contenido del Boletín está estructurado en tres grandes epígrafes: Novedades bibliográficas (clasificadas por su temática y con indicación de su ruta en el caso de que estén disponibles a texto completo en Internet), Legislación y Sumarios de revistas. Esperamos que el Boletín, cuya difusión se realiza a través de listas de distribución de correo electrónico y de su presencia permanente en la página web de la Delegación del Gobierno para el Plan Nacional sobre Drogas, sea de interés y quedamos a la espera de cualquier sugerencia y/o consulta que sobre el mismo queráis formular. Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo. Delegación del Gobierno para el Plan Nacional sobre Drogas José del Val – E-correo: [email protected] Jefe de Servicio del Centro de Documentación e Información 1 Aspectos Generales ........................................................................ 4 Aspectos Sociales ............................................................................ -

Use of the Communication Checklist

Psychiatria Danubina, 2020; Vol. 32, Suppl. 1, pp 88-92 Conference paper © Medicinska naklada - Zagreb, Croatia USE OF THE COMMUNICATION CHECKLIST - SELF REPORT (CC-SR) IN SCHIZOPHRENIA: LANGUAGE IMPAIRMENTS CORRELATE WITH POOR PREMORBID SOCIAL ADJUSTMENT Daria Smirnova1,2, Svetlana Zhukova3, Olga Izmailova4, Ilya Fedotov5, Yurii Osadshiy6, Alexander Shustov7, Anna Spikina8, Dmitriy Ubeikon9, Anna Yashikhina2, Natalia Petrova10, Johanna Badcock1, Vera Morgan1 & Assen Jablensky1 1Centre for Clinical Research in Neuropsychiatry, University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia 2Department of Psychiatry, Narcology, Psychotherapy and Clinical Psychology, Samara State Medical University, Samara, Russia 3Department of Psychiatry, Narcology and Psychology, Ivanovo State Medical Academy, Ivanovo, Russia 4Samara District Clinical Psychiatric Hospital, Samara, Russia 5Department of Psychiatry, Ryazan State Medical University n.a. academician I.P. Pavlov, Ryazan, Russia 6Department of Psychiatry, Narcology and Medical Psychology, Rostov State Medical University, Rostov-on-Don, Russia 7National Medical Research Centre of Psychiatry and Narcology n.a. V.P. Serbsky, Moscow, Russia 8Psychoneurological dispensary ʋ2, Saint Petersburg, Russia 9Department of Psychiatry, Narcology and Psychotherapy with the course of General and Medical psychology, S.I. Georgievsky Medical Academy, V.I. Vernadsky Crimean Federal University, Simferopol, Republic of Crimea, Russia 10Department of Psychiatry and Narcology, Saint Petersburg State University, Saint Petersburg, -

Workbook Psychiatry and Narcology

Kharkiv National Medical University Department of Psychiatry, Narcology and Medical Psychology WORKBOOK MANUAL FOR INDIVIDUAL WORK FOR MEDICAL STUDENTS PSYCHIATRY AND NARCOLOGY (Part 2) Student ___________________________________________________________ Faculty _________________________________________________________ Course _________________ Group _____________________________________ Kharkiv 2019 Затверджено вченою радою ХНМУ Протокол №5 від 23.05.2019 р. Psychiatry (Part 2) : workbook manual for individual work of students / I. Strelnikova, G. Samardacova, К. Zelenska – Kharkiv, 2019. – 103 p. Копіювання для розповсюдження в будь-якому вигляді частин або повністю можливо тільки з дозволу авторів навчального посібника. CLASS 7. NEUROTIC DISORDERS. CLINICAL FORMS. TREATMENT AND REHABILITATION. POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER. TREATMENT AND REHABILITATION. Psychogenic diseases are a large and clinically varied group of diseases resulting from an effect of acute or long-term psychic traumas, which manifest themselves by both mental and somatoneurological disorders and, as a rule, are reversible. Psychogenic diseases are caused by a psychic trauma, i.e. some events which affect significant aspects of existence of the human being and result in deep psychological feelings. These may be subjectively significant events, i.e. those which are pathogenic for the majority of people. Besides, the psyche may be traumatized by conventionally pathogenic events, which cause feelings in an individual because of his peculiar hierarchy of values. Unfavorable psychogenic effects on the human being cause stress in him, i.e. a nonspecific reaction at the physiological, psychological and behavioural levels. Stress may exert some positive, mobilizing influence, but may result in disorganization of the organism activity. The stress, which exerts a negative influence and causes various disturbances and even diseases, is termed distress. Classification of neurotic disorders I. -

Young Psychiatrists' Network Meeting “Stigma from the Yps' Perspective: Hopes and Challenges”, September 27-29 2012, Minsk, Belarus

International conference 3rd Young Psychiatrists’ Network Meeting “Stigma From The YPs' perspective: Hopes and Challenges” September 27-29, 2012 Programme and abstract booklet Ministry of Health of the Republic Of Belarus State Educational Establishment “Belarusian Medical Academy of Post-Graduate Education” Supported by Rotary club “Minsk” International conference 3rd Young Psychiatrists’ Network Meeting “Stigma From The YPs' perspective: Hopes and Challenges” September 27-29, 2012 Programme and abstract booklet Ltd “Magic” Minsk 2012 UDC (УДК) 61 LCN (ББК) 56.14 Scientific edition 3rd Young Psychiatrists' Network Meeting “Stigma From The YPs' perspective: Hopes and Challenges”, September 27-29 2012, Minsk, Belarus. International conference: Programme and abstract booklet. – Minsk: Publishing house “Magic“, 2012. - 84 p. ISBN 978 – 985-6473-81-7 Supported by European Federation of Psychiatrists’ Trainees (EFPT) Supported by Belarusian Medical Academy of Post-Graduate Education (BelMAPGE) Supported by Belarusian Psychiatric Association (BPA) Supported by Rotary club “Minsk” Editorial Board: J. Hanson, MD, PhD, Assoc. Prof., Sweden; D. Krupchanka, MD, PhD student, Belarusian Medical Academy of Postgraduate Education, Minsk, Belarus; N. Bezborodovs, MD, Riga Stradins University, Riga Centre of Psychiatry and Addiction Disorders, Latvia; M. Bendix, MD, Dr. Med., Karolinska University Hospital Huddinge, Sweden; S. Jauhar, MD, MBChB, BSc (Hons), MRCPsych, Department of Psychosis Studies, Institute of Psychiatry, United Kingdom; D. Smirnova, MD, PhD, Samara State Medical University, Russian Federation. ISBN 978 – 985-6473-81-7 © State Educational Establishment “Belarusian Medical Academy of Post- Graduate Education” Anyone who keeps learning stays young. The greatest thing in life is to keep your mind young. (c) There is a story of our meetings. -

Bioethical Differences Between Drug Addiction Treatment Professionals Inside and Outside the Russian Federation Mendelevich

Bioethical differences between drug addiction treatment professionals inside and outside the Russian Federation Mendelevich Mendelevich Harm Reduction Journal 2011, 8:15 http://www.harmreductionjournal.com/content/8/1/15 (10 June 2011) Mendelevich Harm Reduction Journal 2011, 8:15 http://www.harmreductionjournal.com/content/8/1/15 RESEARCH Open Access Bioethical differences between drug addiction treatment professionals inside and outside the Russian Federation Vladimir D Mendelevich Abstract This article provides an overview of a sociological study of the views of 338 drug addiction treatment professionals. A comparison is drawn between the bioethical approaches of Russian and foreign experts from 18 countries. It is concluded that the bioethical priorities of Russian and foreign experts differ significantly. Differences involve attitudes toward confidentiality, informed consent, compulsory treatment, opioid agonist therapy, mandatory testing of students for psychoactive substances, the prevention of mental patients from having children, harm reduction programs (needle and syringe exchange), euthanasia, and abortion. It is proposed that the cardinal dissimilarity between models for providing drug treatment in the Russian Federation versus the majority of the countries of the world stems from differing bioethical attitudes among drug addiction treatment experts. Introduction deontological norms [6,10]. Although there have been Russian and international narcology (addiction medi- calls for adherence to the principles of medical ethics, cine) began to develop along divergent paths during the the procedures put into practicecontinuetobeincom- second half of the twentieth century. Indeed, Russian patible with these principles. Drug addicts still have narcology has ceased to be a part of international nar- even fewer patient rights than the mentally ill. -

Exam Questions Year 5 Psychiatry and Narcology General Medicine Faculty BSMU (2019/2020)

Exam questions Year 5 Psychiatry and narcology General medicine faculty BSMU (2019/2020) Part 1 1. Object and task of psychiatry and narcology, their place among other medical disciplines. 2. History of psychiatry: middle ages, 19th century, modern psychiatry. 3. Stigma of mental Illness. Central anti-psychiatry beliefs. 4. Frame of psychiatry: general psychopathology, age psychiatry, organizational psychiatry, judicial, psychopharmacotherapy, addictology (narcology), trans-cultural psychiatry, sexology, suicidology. 5. The methods of investigations in psychiatry. 6. The criteria of mental health. Criteria of normality (Rosenhan and Seligman, 1984). 7. Biases that affect diagnoses: racial/ethnic, confirmation bias, institutionalization, reporting bias, cultural differences. 8. Classification in psychiatry, the most important classification categories. 9. Organic and functional disorders in psychiatry. Concepts of neurosis and psychosis. 10. Epidemiology of mental disorders. Prevalence of major psychiatric conditions. 11. Psychiatry examination. 12. Disturbances of perception: hallucinations, types of hallucinations. Pseudo-hallucinations. Circumstances and disorders associated with hallucinations. 13. Disturbances of perception: illusions, types of illusions. 14. Psycho-sensorial disturbances of perception: derealisation, dismorphophobia, methamorphopsias, and depersonalisation. 15. Disorders of mood (emotions): pathological affect, depression, mania, anhedonia, flattened affect, euphoria, emotional lability, inappropriate affect, phobias. -

NGO Directory

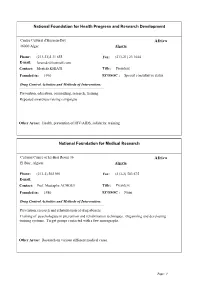

National Foundation for Health Progress and Research Development Centre Culturel d'Hussein-Day Africa 16000 Alger Algeria Phone: (213-21)2 31 655 Fax: (213-21) 23 1644 E-mail: [email protected] Contact: Mostefa KHIATI Title: President Founded in: 1990 ECOSOC : Special consultative status Drug Control Activities and Methods of Intervention: Prevention, education, counselling, research, training Repeated awareness raising campaigns Other Areas: Health, prevention of HIV/AIDS, solidarity, training National Foundation for Medical Research Cultural Centre of El-Biar Room 36 Africa El Biar, Algiers Algeria Phone: (213-2) 502 991 Fax: (213-2) 503 675 E-mail: Contact: Prof. Mustapha ACHOUI Title: President Founded in: 1980 ECOSOC : None Drug Control Activities and Methods of Intervention: Prevention, research and rehabilitation of drug abusers. Training of psychologists in prevention and rehabilitation techniques. Organizing and developing training systems. Target groups contacted with a few monographs. Other Areas: Research on various different medical cases. Page: 1 Movimento Nacional Vida Livre M.N.V.L. Av. Comandante Valodia No. 283, 2. And.P.24. Africa C.P. 3969 Angola, Rep. Of Luanda Phone: (244-2) 443 887 Fax: E-mail: Contact: Dr. Celestino Samuel Miezi Title: National Director, Professor Founded in: 1989 ECOSOC : Drug Control Activities and Methods of Intervention: Prevention, education, treatment, counselling, rehabilitation, training, and criminology To combat drugs and its consequences through specialized psychotherapy and detoxification Other Areas: Health, psychotherapy, ergo therapy Maison Blanche (CERMA) 03 BP 1718 Africa Cotonou Benin Phone: (229) 300850/302816 Fax: (229) 30 04 26 E-mail: Contact: Prof. Rene Gilbert AHYI Title: President Founded in: 1988 ECOSOC : None Drug Control Activities and Methods of Intervention: Prevention, treatment, training and education. -

Abuse Treatment and Rehabilitation

Drug Abuse Treatment Toolkit Printed in Austria V.02-59610—July 2003—1,150 DRUG ABUSE GUIDE PRACTICAL PLANNING AND IMPLEMENTATION AND REHABILITATION—A TREATMENT Back to navigation page Drug Abuse Treatment and Rehabilitation A Practical Planning and Implementation Guide United Nations publication Sales No. E.03.XI.II B ISBN 92-1-148160-0 UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna Drug Abuse Treatment and Rehabilitation: a Practical Planning and Implementation Guide UNITED NATIONS New York, 2003 The Office for Drug Control and Crime Prevention became the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime on 1 October 2002. UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No. E.03.XI.II ISBN 92-1-148160-0 The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expres- sion of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or the delimitation of any frontiers or boundaries. ii Acknowledgements The present text of Drug Abuse Treatment and Rehabilitation: a Practical Planning and Implementation Guide was commissioned by the Demand Reduction Section of the United Nations International Drug Control Programme (UNDCP). For their contributions to the preparation of the Guide, UNDCP would like to express its gratitude to the following: • The consultant project team: Dr. John Marsden, National Addiction Centre, Institute of Psychiatry, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland; Dr. Robert Ali, Drug and Alcohol Services Council, Adelaide, South Australia; Dr. Michael Farrell, National Addiction Centre, Institute of Psychiatry, United Kingdom; and Dr. -

This Year 2017 in Aperplexing World

sph this year 2017 in a perplexing world. in aperplexing THOUGHT “ Our core purpose commits us to redouble our eort to ensure that we narrow these divides to produce the science and scholarship that contributes to a better, healthier world for all.” DEAR COLLEAGUES: WELCOME TO SPH THIS YEAR, our School’s us to always ask what the role of public health is in annual report. these changing times. To that end, while in this issue Our School’s core purpose is “Think. Teach. Do. of SPH This Year we feature the work of the School, For the health of all.” This aims to describe and we also feature 23 deans and program directors of animate what we do: we generate ideas through our other schools and programs talking about the role scholarship and research, think; we transmit this of public health in these times—their comments knowledge to the next generation, teach; and we work are captured on pages 46 to 49 of this issue and on to communicate these ideas and be a part of the the web at bu.edu/sph/thisyear17—who create a action that contributes to a healthier world, do. This compelling portrait of the central role that academic issue of SPH This Year focuses on our scholarship at public health stands to play in the years ahead. Thank a time when thought and science have become more you to all of our colleagues who participated in these important than ever. interviews; we learned from all your comments and Over the past year, we have seen the country— are excited to work together in the coming years. -

{FREE} the Psychiatric Interview Kindle

THE PSYCHIATRIC INTERVIEW PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Daniel J. Carlat | 348 pages | 01 Oct 2016 | Lippincott Williams and Wilkins | 9781496327710 | English | Philadelphia, United States The Psychiatric Interview | SIMPLY PSYCH EDU Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Helen Swick Perry Editor ,. Otto Allen Will Introduction. This is a book for all those working in the field of psychiatric disorder. It will be invaluable to medical students and doctors training in general practice, emergency medicine and psychiatry. At a time when the assessment of psychiatric patients is the responsibility of a range of clinicians, The Psychiatric Interview will also be of assistance to clinical psychologists, This is a book for all those working in the field of psychiatric disorder. At a time when the assessment of psychiatric patients is the responsibility of a range of clinicians, The Psychiatric Interview will also be of assistance to clinical psychologists, social workers and psychiatric nurses. It will also have a place as a reference book for police and security officers. Get A Copy. Paperback , pages. Published February 17th by W. Norton Company first published February More Details Original Title. Other Editions 2. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about The Psychiatric Interview , please sign up. Be the first to ask a question about The Psychiatric Interview. Lists with This Book. -

Drugs and New Potentially Dangerous Chemical Substances, with a Brief Review of the Problem

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ENVIRONMENTAL & SCIENCE EDUCATION 2016, VOL. 11, NO. 14, 6697-6703 OPEN ACCESS Approach to Classifying “Design” Drugs and New Potentially Dangerous Chemical Substances, With a Brief Review of the Problem Azat R. Asadullina, Elena Kh. Galeevab, Elvina A. Achmetovaa and Ivan V. Nikolaevb aBashkir State Medical University of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Ufa, RUSSIA; bRepublican Narcological Dispensary No.1 of the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Bashkortostan, Ufa, RUSSIA ABSTRACT The urgency of this study has become vivid in the light of the growing problem of prevalence and bBPHFuse Republican of new synthetic Narcological drug types. DispensaryLately there has No.1 been of a thetendency Ministry of expanding of Health the rangeof the of psychologically active substances (PAS) used by addicts with the purpose of their illegal taking. RepublicThe aim of Bashkortostan,of this research is anPushkin attempt str.,of systematizing 119/1, Ufa, and RB. classifying “design” drugs according to their chemical structure, neurochemical mechanisms of action and clinical manifestations. As a result, we have found that they can be divided into ten big groups. This classification will allow to better arrange new clinical phenomenology in modern addictology. This paper would be useful for psychiatrists, experts in narcology, as well as for personnel of institutions and agencies engaged in anti-drug activity. KEYWORDS ARTICLE HISTORY Opiates, cannabinoids, cathinones, tryptamine, Received 20 April 2016 cocaine, pregabalin, new “design” drugs, Revised 28 May 2016 classification Accepted 29 Мау 2016 Introduction Urgency of the problem Recently, the sphere of illegal turnover of narcotic substances has shown an apparent trend of producing the so-called “design drugs” (DN): new potentially dangerous psychologically active substances (NPDPAS) obtained by means of chemical synthesis, possessing a high narcotic effect and manufactured with the CORRESPONDENCE Azat R.