Four Quarters Volume 207 Number 1 Four Quarters (Second Series): Spring Article 1 1993 Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2010–2011 Season Sponsors

2010–2011 SEASON SPONSORS The City of Cerritos gratefully thanks our 2010–2011 Season Sponsors for their generous support of the Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts. YOUR FAVORITE ENTERTAINERS, YOUR FAVORITE THEATER If your company would like to become a Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts sponsor, please contact the CCPA Administrative Offices at 562-916-8510. THE CERRITOS CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS (CCPA) thanks the following CCPA Associates who have contributed to the CCPA’s Endowment Fund. The Endowment Fund was established in 1994 under the visionary leadership of the Cerritos City Council to ensure that the CCPA would remain a welcoming, accessible, and affordable venue in which patrons can experience the joy of entertainment and cultural enrichment. For more information about the Endowment Fund or to make a contribution, please contact the CCPA Administrative Offices at (562) 916-8510. Benefactor Jill and Steve Edwards Ilana and Allen Brackett Erin Delliquadri $50,001-$100,000 Dr. Stuart L. Farber Paula Briggs Ester Delurgio José Iturbi Foundation William Goodwin Scott N. Brinkerhoff Rosemarie and Joseph Di Giulio Janet Gray Darrell Brooke Rosemarie diLorenzo Sandra and Bruce Dickinson Patron Rosemary Escalera Gutierrez Mary Brough Marianne and Bob Hughlett, Ed. D. Joyce and Russ Brown Amy and George Dominguez $20,001-$50,000 Robert M. Iritani Dr. and Mrs. Tony R. Brown Mrs. Abiatha Doss Bryan A. Stirrat & Associates Dr. HP Kan and Mrs. Della Kan Cheryl and Kerry Bryan Linda Dowell National Endowment for the Arts Jill and Rick Larson Florence P. Buchanan Robert Dressendorfer Eleanor and David St. -

Pathetique Symphony New York Philharmonic/Bernstein Columbia

Title Artist Label Tchaikovsky: Pathetique Symphony New York Philharmonic/Bernstein Columbia MS 6689 Prokofiev: Two Sonatas for Violin and Piano Wilkomirska and Schein Connoiseur CS 2016 Acadie and Flood by Oliver and Allbritton Monroe Symphony/Worthington United Sound 6290 Everything You Always Wanted to Hear on the Moog Kazdin and Shepard Columbia M 30383 Avant Garde Piano various Candide CE 31015 Dance Music of the Renaissance and Baroque various MHS OR 352 Dance Music of the Renaissance and Baroque various MHS OR 353 Claude Debussy Melodies Gerard Souzay/Dalton Baldwin EMI C 065 12049 Honegger: Le Roi David (2 records) various Vanguard VSD 2117/18 Beginnings: A Praise Concert by Buryl Red & Ragan Courtney various Triangle TR 107 Ravel: Quartet in F Major/ Debussy: Quartet in G minor Budapest String Quartet Columbia MS 6015 Jazz Guitar Bach Andre Benichou Nonsuch H 71069 Mozart: Four Sonatas for Piano and Violin George Szell/Rafael Druian Columbia MS 7064 MOZART: Symphony #34 / SCHUBERT: Symphony #3 Berlin Philharmonic/Markevitch Dacca DL 9810 Mozart's Greatest Hits various Columbia MS 7507 Mozart: The 2 Cassations Collegium Musicum, Zurich Turnabout TV-S 34373 Mozart: The Four Horn Concertos Philadelphia Orchestra/Ormandy Mason Jones Columbia MS 6785 Footlifters - A Century of American Marches Gunther Schuller Columbia M 33513 William Schuman Symphony No. 3 / Symphony for Strings New York Philharmonic/Bernstein Columbia MS 7442 Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 in D minor Westminster Choir/various artists Columbia ML 5200 Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 6 (Pathetique) Philadelphia Orchestra/Ormandy Columbia ML 4544 Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 5 Cleveland Orchestra/Rodzinski Columbia ML 4052 Haydn: Symphony No 104 / Mendelssohn: Symphony No 4 New York Philharmonic/Bernstein Columbia ML 5349 Porgy and Bess Symphonic Picture / Spirituals Minneapolis Symphony/Dorati Mercury MG 50016 Beethoven: Symphony No 4 and Symphony No. -

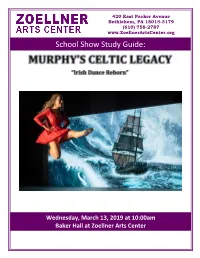

School Show Study Guide

420 East Packer Avenue Bethlehem, PA 18015-3179 (610) 758-2787 www.ZoellnerArtsCenter.org School Show Study Guide: Wednesday, March 13, 2019 at 10:00am Baker Hall at Zoellner Arts Center USING THIS STUDY GUIDE Dear Educator, On Wednesday, March 13, your class will attend a performance by Murphy’s Celtic Legacy, at Lehigh University’s Zoellner Arts Center in Baker Hall. You can use this study guide to engage your students and enrich their Zoellner Arts Center field trip. Materials in this guide include information about the performance, what you need to know about coming to a show at Zoellner Arts Center and interesting and engaging activities to use in your classroom prior to and following the performance. These activities are designed to go beyond the performance and connect the arts to other disciplines and skills including: Dance Culture Expression Social Sciences Teamwork Choreography Before attending the performance, we encourage you to: Review the Know before You Go items on page 3 and Terms to Know on pages 9. Learn About the Show on pages 4. Help your students understand Ireland on pages 11, the Irish dance on pages 17 and St. Patrick’s Day on pages 23. Engage your class the activity on pages 25. At the performance, we encourage you to: Encourage your students to stay focused on the performance. Encourage your students to make connections with what they already know about rhythm, music, and Irish culture. Ask students to observe how various show components, like costumes, lights, and sound impact their experience at the theatre. After the show, we encourage you to: Look through this study guide for activities, resources and integrated projects to use in your classroom. -

John Mccormack 1843-1997 IM.M035.1998

Frederick M. Manning Collection of John McCormack 1843-1997 IM.M035.1998 http://hdl.handle.net/2345/956 Irish Music Archives John J. Burns Library Boston College 140 Commonwealth Avenue Chestnut Hill 02467 library.bc.edu/burns/contact URL: http://www.bc.edu/burns Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Biographical Note: John McCormack ........................................................................................................... 5 Biographical Note: Frederick M. Manning ................................................................................................... 5 Scope and Contents ........................................................................................................................................ 6 Arrangement ................................................................................................................................................... 6 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 7 I: Correspondence ........................................................................................................................................ 7 II: Manuscripts and Typescripts by John McCormack -

Carlow H1scor1cal Ant> Archaeolo51ca L Soc1ecy

caRlow h1scoR1cal ant> aRchaeolo51ca l soc1ecy cumonn sco1Re 05us seonoa lofochco cheochoRloch 2006 EDITION dmhly um("' 'I, J'lu:, I ,, u, 11,r(f, /. Heritage Week 2006 Local History and On-Line Sources Winter Lectures Series For the Bookshelves Carlow Remembers Michael O'Hanrahan St. Laserian's Cathedral, Old Leighlin The 1841 Census Ballon Hill and The Lecky Collection The O'Meara's of Carlow Music in Carlow A Most Peculiar Carlow Murder Trial 60th Anniversary Dinner Carlow's Most Famous Benefactor Opening of Carlow Railway Station Old Carlow Society, Carlow Historical & Bishop Foley and Two Crises Archaeological Society 1946 - 2006 Memories and Musings Mid Carlow Words of the 1950's The Holy Wells of County Carlow SPONSORS CARBERY CONSTRUCTION LTD. HOSEYS BUILDING CONTRACTORS RETAIL STORES AND WHOLESALE FRUIT MERCHANT Green Road, Carlow. Staplestown Road, Carlow. Tel: 059 9143252. Fax: 059 9132291. Tel: 059 9131562 SHAW & SONS LTD. GAELSCOIL EOGHAIN UI THUAIRISC SHAW~ TULLOW STREET, CARLOW. BOTHAR POLLERTON Tel: (059) 9131509 Guthan 059 9131634 Faics 059 9140861 Almost Nationwide Fax: (059) 9141522 www.iol.ie/-cgscoil MATT D. DOYLE A.I.B. MONUMENTAL WORKS 36-37 TULLOW STREET, CARLOW. Pembroke, Carlow. Serving Carlow since late 1880s Tel: 059 9142048. Mobile: 087 2453413. Fax: 059 9142048 Branch Manager: Eddie Deegan. Manager: Barry Hickey. Email: [email protected] Web: www.mattdoyle.com Tel: 059 9131758 R. HEALY & SON KNOCKBEG COLLEGE, CARLOW FUNERAL DIRECTORS BOARDING AND DAY SCHOOL FOR BOYS Phone: 059 9142127. Fax: 059 9143705. Pollerton Castle, Carlow. Email: [email protected] Web: www.knockbegcollege.ie Phone: 059/9131286 O'NEILL & CO. -

2012–2013 Season Sponsors

2012–2013 SEASON SPONSORS The City of Cerritos gratefully thanks our 2012–2013 Season Sponsors for their generous support of the Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts. YOUR FAVORITE ENTERTAINERS, YOUR FAVORITE THEATER If your company would like to become a Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts sponsor, please contact the CCPA Administrative Offices at 562-916-8510. THE CERRITOS CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS (CCPA) thanks the following CCPA Associates who have contributed to the CCPA’s Endowment Fund. The Endowment Fund was established in 1994 under the visionary leadership of the Cerritos City Council to ensure that the CCPA would remain a welcoming, accessible, and affordable venue in which patrons can experience the joy of entertainment and cultural enrichment. For more information about the Endowment Fund or to make a contribution, please contact the CCPA Administrative Offices at (562) 916-8510. ENCORE Terry Bales Patricia and Mitchell Childs Bryan A. Stirrat & Associates Sallie Barnett Drs. Frances and Philip Chinn The Capital Group Companies Alan Barry Nancy and Lance Chontos Charitable Foundation Cynthia Bates Patricia Christie Jose Iturbi Foundation Dennis Becker Richard “Dick” Christy National Endowment for the Arts Barbara S. Behrens Rozanne and James Churchill Eleanor and David St. Clair Aldenise Belcer Neal Clyde Yvette Belcher Mark Cochrane HEADLINER Peggy Bell Michael Cohn Chamber Music Society of Detroit Morris Bernstein Claire Coleman The Gettys Family Norman Blanco Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Consani II Los Cerritos Center James Blevins Patricia Cookus Preserved TreeScapes International, Michael Bley Christina and Robert Copella Dennis E. Gabrick Kathleen Blomo Nancy Corralejo Marilynn and Art Segal Karen Bloom Virginia Correa Triangle Distributing Company Marilyn Bogenschutz Ron Cowan United Parcel Service Linda and Sergio Bonetti Patricia Cozzini Yamaha Patricia Bongeorno Pamela and John Crawley Gloria and Lester Boston, Jr. -

Music As of SCN Media Center Catalog 10/20/2014

SCN Media Center Catalog Music as of 10/20/2014 Music A Love So Strong Sherman, Kathy, CSJ CD 1 42:37 2011 Thirteen songs sung by Kathy Sherman. I Come to Know You Singing Bird Love So Strong Come Walk with Us What If We Believe In the Becoming I Give Thanks to God It's3:23 in the Morning Peace Prints on the World Love Bears All Things Tell It Like It Is Now Is All You Need Let Your Light All Is One Sherman, Kathy, CSJ CD 1 69 min. 2006 Twenty songs for rituals, gatherings justice, liturgy and meditation. All My Days: Instrumental Music for Quiet Reflection Schutte, Dan CD 1 55 min. 2006 All My Days, the latest collection of instrumental tracks from Dan Schutte, provides over 50 minutes of gentle, quiet reflective music for background for personal prayer. This CD includes piano, oboe, flute, cello, violin and other strings. All the Seasons of George Winston Winston, George CD 1 63 min. 1998 Piano solos of radio hits of the 50's and 60's. Page 1 of 103 Music All Time Great Rags Joplin, Scott CD 1 71 min. 2000 Eighteen selections from the best known of all ragtime composers. Allegri Miserere Phillips, Peter, Director CD 1 69 min. 1980 orig. 1990 Finest music from the Golden Age that has more performances than any other sacred music selections. Always With You Sherman, Kathy, CSJ Cassette Tape 2003 Eight spiritual hymns. Always With You Sherman, Kathy, CSJ CD 1 56 min. 2003 Slection of meditative songs for your own personal reflection. -

Newsbulletin Vol. 21, No. 5

Salve Regina University Digital Commons @ Salve Regina Newsbulletin Archives and Special Collections Summer 1990 Newsbulletin vol. 21, no. 5 Salve Regina College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/newsbulletin Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Salve Regina College, "Newsbulletin vol. 21, no. 5" (1990). Newsbulletin. 429. https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/newsbulletin/429 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Special Collections at Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. It has been accepted for inclusion in Newsbulletin by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE VOL. 21 NO. 5 Summer 1990 SAL VE REGINA COLLEGE Salve Regina Holds Fortieth Commencement Exercises Students Receive Awards at Annual Salve Regina College held its fortieth commencement exercises Honors Convocation Sunday, May 20 at 10 a.m. on the Salve Regina College held its east lawn of the O'Hare Academic annual Honors Convocation on Center. Six hundred and fifty-nine Saturday, April 27 in the Spruance degrees were conferred under a tent Auditorium at the Naval War standing adjacent to Newport's College. The event recognizes and scenic Cliff Walk. honors students who have excelled Dr. Lucille McKillop, R.S.M., in scholarship, campus leadership President of Salve Regina, addressed and community service. Over 230 this year's graduating class with the .. students received honors. Commencement Message, and Dr. Among the most prestigious M. Therese Antone, R.S.M., Vice honors is the valedictory award . President for Institutional - Samir Uberoi, a financial Advancement, inducted the 1990 • management major from Bombay, graduates into the College's Alumni India, the College valedictorian this Association. -

American Irish Newsletter the Ri Ish American Community Collections

Sacred Heart University DigitalCommons@SHU American Irish Newsletter The rI ish American Community Collections 11-1989 American Irish Newsletter - November 1989 American Ireland Education Foundation - PEC Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/irish_ainews Part of the European Languages and Societies Commons, Other American Studies Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation American Ireland Education Foundation - PEC, "American Irish Newsletter - November 1989" (1989). American Irish Newsletter. Paper 141. http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/irish_ainews/141 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by the The rI ish American Community Collections at DigitalCommons@SHU. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Irish Newsletter by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@SHU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AMERICAN IRISH NEWSLEHER AMERICAN Irish Political Education Committee_______________________________________ Volume 14, Number 11 November 1989 NEWS BITS by Kathy Regan MEMBERSHIP RENEWAL NOTICE APPEARS In an interview with MP Ken Livingstone, Albert Baker, a ON PAGE 6 JUST BELOW YOUR ADDRESS convicted Protestant assassin, has made detailed allegations of LABEL. direct involvement by the RUC and British intelligence in sectarian murders in Northern Ireland in the early seventies. He alleges that the vice-chairman of the UDA Tommy Herron VOLUNTEERS TO LOBBY CONGRESS was directly contacted through a “cut out” by a senior army intelligence officer codenamed “Bunty”...He details incidents The PEC wants to organize a select group of men and in which RUC officers allege providing weapons to the UDA [a women for the purpose of lobbying our issues in the nation’s pro-British para-military organization alleged to be respon Capitol. -

October 1942) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 10-1-1942 Volume 60, Number 10 (October 1942) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 60, Number 10 (October 1942)." , (1942). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/234 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. P / * i Mr' ium \ 1 r ml 1 taM$££{ S i STAMPS c ” conduct DR. WALTER DAMROSCH will opera, the world premiere of his new “The Opera Cloak,” when it is presented York by the New Opera Company of New which City during its second season, directoi opens on November 3. The stage £uentiJ produc- . Q. Succeii Brentano and the . , ,/)/ a will be Felix I’lanruru} B. “Jjvance tion will be designed by Eugene M " Dunkel. ss PB0™ NICOLAI MALKO, conductor of the Chi- Cini,s™ and former fob tm cago Woman’s Symphony JLMUclJJLue , guest conductor at Ravinia, is announced mm c^- Rapids (Mich- "o» ~ as conductor of the Grand r z 1942- c— f° •r&izrt&ii igan) Symphony Orchestra for the See Them a Offerings SHEPHERDS WATCHED 43 season. -

2011–2012 Season Sponsors

SEASON CERRITOS CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS 2011–2012 SEASON SPONSORS The City of Cerritos gratefully thanks our 2011–2012 Season Sponsors for their generous support of the Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts. SEASON YOUR FAVORITE ENTERTAINERS, YOUR FAVORITE THEATER If your company would like to become a Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts sponsor, please contact the CCPA Administrative Offices at 562-916-8510. SEASON CERRITOS CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS THE CERRITOS CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS (CCPA) thanks the following CCPA Associates who have contributed to the CCPA’s Endowment Fund. The Endowment Fund was established in 1994 under the visionary leadership of the Cerritos City Council to ensure that the CCPA would remain a welcoming, accessible, and affordable venue in which patrons can experience the joy of entertainment and cultural enrichment. For more information about the Endowment Fund or to make a contribution, please contact the CCPA Administrative Offices at (562) 916-8510. ENCORE Beth Anderson Rodolfo Chavez Bryan A. Stirrat & Associates Hedy Harrison-Anduha and Liming Chen Jose Iturbi Foundation Larry Anduha Wanda Chen National Endowment for the Susan and Clifford Asai Margie and Ned Cherry Arts Larry Baggs Frances and Philip Chinn Eleanor and David St. Clair Marilyn Baker Nancy and Lance Chontos Terry Bales Patricia Christie HEADLINER Sallie Barnett Richard Christy The Capital Group Companies Alan Barry Rozanne and James Churchill Charitable Foundation Cynthia Bates Neal Clyde Chamber Music Society of Dennis Becker Mark Cochrane Detroit Barbara S. Behrens Michael Cohn The Gettys Family Aldenise Belcer Claire Coleman Los Cerritos Center Yvette Belcher Mr. -

Newsbulletin Vol. 16, No. 15

Salve Regina University Digital Commons @ Salve Regina Newsbulletin Archives and Special Collections 5-1-1986 Newsbulletin vol. 16, no. 15 Salve Regina College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/newsbulletin Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Salve Regina College, "Newsbulletin vol. 16, no. 15" (1986). Newsbulletin. 373. https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/newsbulletin/373 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Special Collections at Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. It has been accepted for inclusion in Newsbulletin by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SALVE REGINA C) THE NEWPORT COLLEGE NEWSBULLETIN Published by the Office of Public Relations, Ext. 208 ' Vol. 16 No. 15 May 1, 1986 SALVE REGINA WILL PRESENT FRANK PATTERSON CONCERT AT ROGERS Salve Regi na's Irish Festival Committee will present Frank Patters on i n ~oncer t a t the Rogers High School auditorium in Newpor t on Sunday, {\~ay 4. Patter son is widely recognized as Ireland's greatest tenor. In 1981 h e performed in Ne w York at President Reagan's acceptance of the Amer ican Irish Soc iety's gold medal. Patterson has sold out Carnegie Hall and has g i ven other U. S. performances at Heinz Hall, Li ncoln Cente r and the Sm ithsonian Institution. The popular tenor is much in demand throughout Europe for oratorio, concert recitals, and radio and television appearances. He has completed four coast-to-coast tout s of the United States and has also given concerts in the West Indies , the Middle East and Australia.