Sound in the Adaptations of John Huston

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mla Style Guide for Bibliographical Citations

American School of Valencia Library MLA STYLE GUIDE FOR BIBLIOGRAPHICAL CITATIONS Used primarily for: Liberal Arts and Humanities. Some general things to know: MLA calls the list of bibliographical citations at the end of a paper the “Works Cited” page, and not a bibliography. Also, like APA, MLA style does not use bibliographical footnotes, favoring instead in-text citations. Footnotes and endnotes are only used for the purposes of authorial commentary. For full entries, titles of books are italicized*, and in-text citations tend to be as brief as possible. See some common examples below. If you don’t see an example that fits the kind of source you have, consult an MLA style guide in the Library, or ask the Librarian. Every line after the first is indented in the full citation. And remember, pay close attention to the examples. Punctuation is very important. * (This reflects a change made in 2009. All information provided in this document is based on the 7th edition of the MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers, available in the Library) For all examples below, the information following “Works Cited:” is what goes into your Works Cited page. The information following “In-Text:” is what goes at the end of your sentence that includes a citation. A BOOK: Author’s last name, First name. Title of the book. City: Publisher, year. Medium (Print). (Example) Works Cited: Smith, John G. When citation is almost too much fun. Trenton: Nice People Publications, 2007. Print. In-Text: (Smith 13) or (13) *if it’s obvious in the sentence’s context that you’re talking about Smith+ or (Smith, Citation 9-13) [to differentiate from another book written by the same Smith in your Works Cited] [If a book has more than one author, invert the names of the first author, but keep the remaining author names as they are. -

A Formalist Critique of Three Crime Films by Joel and Ethan Coen Timothy Semenza University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Honors Scholar Theses Honors Scholar Program Spring 5-6-2012 "The wicked flee when none pursueth": A Formalist Critique of Three Crime Films by Joel and Ethan Coen Timothy Semenza University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/srhonors_theses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Semenza, Timothy, ""The wicked flee when none pursueth": A Formalist Critique of Three Crime Films by Joel and Ethan Coen" (2012). Honors Scholar Theses. 241. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/srhonors_theses/241 Semenza 1 Timothy Semenza "The wicked flee when none pursueth": A Formalist Critique of Three Crime Films by Joel and Ethan Coen Semenza 2 Timothy Semenza Professor Schlund-Vials Honors Thesis May 2012 "The wicked flee when none pursueth": A Formalist Critique of Three Crime Films by Joel and Ethan Coen Preface Choosing a topic for a long paper like this can be—and was—a daunting task. The possibilities shot up out of the ground from before me like Milton's Pandemonium from the soil of hell. Of course, this assignment ultimately turned out to be much less intimidating and filled with demons than that, but at the time, it felt as though it would be. When you're an English major like I am, your choices are simultaneously extremely numerous and severely restricted, mostly by my inability to write convincingly or sufficiently about most topics. However, after much deliberation and agonizing, I realized that something I am good at is writing about film. -

2010–2011 Season Sponsors

2010–2011 SEASON SPONSORS The City of Cerritos gratefully thanks our 2010–2011 Season Sponsors for their generous support of the Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts. YOUR FAVORITE ENTERTAINERS, YOUR FAVORITE THEATER If your company would like to become a Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts sponsor, please contact the CCPA Administrative Offices at 562-916-8510. THE CERRITOS CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS (CCPA) thanks the following CCPA Associates who have contributed to the CCPA’s Endowment Fund. The Endowment Fund was established in 1994 under the visionary leadership of the Cerritos City Council to ensure that the CCPA would remain a welcoming, accessible, and affordable venue in which patrons can experience the joy of entertainment and cultural enrichment. For more information about the Endowment Fund or to make a contribution, please contact the CCPA Administrative Offices at (562) 916-8510. Benefactor Jill and Steve Edwards Ilana and Allen Brackett Erin Delliquadri $50,001-$100,000 Dr. Stuart L. Farber Paula Briggs Ester Delurgio José Iturbi Foundation William Goodwin Scott N. Brinkerhoff Rosemarie and Joseph Di Giulio Janet Gray Darrell Brooke Rosemarie diLorenzo Sandra and Bruce Dickinson Patron Rosemary Escalera Gutierrez Mary Brough Marianne and Bob Hughlett, Ed. D. Joyce and Russ Brown Amy and George Dominguez $20,001-$50,000 Robert M. Iritani Dr. and Mrs. Tony R. Brown Mrs. Abiatha Doss Bryan A. Stirrat & Associates Dr. HP Kan and Mrs. Della Kan Cheryl and Kerry Bryan Linda Dowell National Endowment for the Arts Jill and Rick Larson Florence P. Buchanan Robert Dressendorfer Eleanor and David St. -

Pathetique Symphony New York Philharmonic/Bernstein Columbia

Title Artist Label Tchaikovsky: Pathetique Symphony New York Philharmonic/Bernstein Columbia MS 6689 Prokofiev: Two Sonatas for Violin and Piano Wilkomirska and Schein Connoiseur CS 2016 Acadie and Flood by Oliver and Allbritton Monroe Symphony/Worthington United Sound 6290 Everything You Always Wanted to Hear on the Moog Kazdin and Shepard Columbia M 30383 Avant Garde Piano various Candide CE 31015 Dance Music of the Renaissance and Baroque various MHS OR 352 Dance Music of the Renaissance and Baroque various MHS OR 353 Claude Debussy Melodies Gerard Souzay/Dalton Baldwin EMI C 065 12049 Honegger: Le Roi David (2 records) various Vanguard VSD 2117/18 Beginnings: A Praise Concert by Buryl Red & Ragan Courtney various Triangle TR 107 Ravel: Quartet in F Major/ Debussy: Quartet in G minor Budapest String Quartet Columbia MS 6015 Jazz Guitar Bach Andre Benichou Nonsuch H 71069 Mozart: Four Sonatas for Piano and Violin George Szell/Rafael Druian Columbia MS 7064 MOZART: Symphony #34 / SCHUBERT: Symphony #3 Berlin Philharmonic/Markevitch Dacca DL 9810 Mozart's Greatest Hits various Columbia MS 7507 Mozart: The 2 Cassations Collegium Musicum, Zurich Turnabout TV-S 34373 Mozart: The Four Horn Concertos Philadelphia Orchestra/Ormandy Mason Jones Columbia MS 6785 Footlifters - A Century of American Marches Gunther Schuller Columbia M 33513 William Schuman Symphony No. 3 / Symphony for Strings New York Philharmonic/Bernstein Columbia MS 7442 Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 in D minor Westminster Choir/various artists Columbia ML 5200 Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 6 (Pathetique) Philadelphia Orchestra/Ormandy Columbia ML 4544 Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 5 Cleveland Orchestra/Rodzinski Columbia ML 4052 Haydn: Symphony No 104 / Mendelssohn: Symphony No 4 New York Philharmonic/Bernstein Columbia ML 5349 Porgy and Bess Symphonic Picture / Spirituals Minneapolis Symphony/Dorati Mercury MG 50016 Beethoven: Symphony No 4 and Symphony No. -

The Role of Irish-Language Film in Irish National Cinema Heather

Finding a Voice: The Role of Irish-Language Film in Irish National Cinema Heather Macdougall A Thesis in the PhD Humanities Program Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada August 2012 © Heather Macdougall, 2012 ABSTRACT Finding a Voice: The Role of Irish-Language Film in Irish National Cinema Heather Macdougall, Ph.D. Concordia University, 2012 This dissertation investigates the history of film production in the minority language of Irish Gaelic. The objective is to determine what this history reveals about the changing roles of both the national language and national cinema in Ireland. The study of Irish- language film provides an illustrative and significant example of the participation of a minority perspective within a small national cinema. It is also illustrates the potential role of cinema in language maintenance and revitalization. Research is focused on policies and practices of filmmaking, with additional consideration given to film distribution, exhibition, and reception. Furthermore, films are analysed based on the strategies used by filmmakers to integrate the traditional Irish language with the modern medium of film, as well as their motivations for doing so. Research methods included archival work, textual analysis, personal interviews, and review of scholarly, popular, and trade publications. Case studies are offered on three movements in Irish-language film. First, the Irish- language organization Gael Linn produced documentaries in the 1950s and 1960s that promoted a strongly nationalist version of Irish history while also exacerbating the view of Irish as a “private discourse” of nationalism. Second, independent filmmaker Bob Quinn operated in the Irish-speaking area of Connemara in the 1970s; his fiction films from that era situated the regional affiliations of the language within the national context. -

Filmindex Lxxiv

Tarzan And His Mate. (Tarzan og den hvide Pige). MGM. 1934. I : Cedric Gibbons & JaCk Conway. M : J. K. MCGuinness & Leon Gordon. F: Char Filmindex l x x iv les Clarke & Clyde De Vinna. Medv.: Johnny TARZAN-FILM Weissmuller, Maureen O’Sullivan, Neil Hamil- ton, Paul Cavanaugh, Forrester Harvey, Nathan Curry, Doris Lloyd, William Stack, Desmond A f Janus Barfoed Roberts. D-Prm: 10/12-1934. The New Adventures O f Tarzan. (Tarzans nye Even tyr). Burroughs-Tarzan Enterprises. 1935. I: Ed (S) = serial ward Kuli & W. F. MCGaugh. M : Charles F. Tarzan Of The Apes. National Film Corp. 1918. Royal. F : Edward Kuli & Ernest F. Smith. Instr.: Sidney Scott. Medv.: Elmo LinColn, Enid Medv.: Herman Brix, Ula Holt, Frank Baker, Markey, Gordon Griffith, George French, True Dale Walsh, Harry Ernest, Don Costello, Lewis Boardman, Kathleen Kirkham, Colin Kenny. Sargent, Merrill McCormick. D-Prm: 17/8-1936. Romance Of Tarzan. National Film Corp. 1918. I: Tarzan And The Green Goddess. (Tarzan og den Wilfred Lucas. Medv.: Bess Meredyth, Elmo Lin grønne Gudinde). Burroughs-Tarzan Enterprises. Coln, Enid Markey, Thomas Jefferson, Cleo Ma- 1935. I: Edward Kuli. M: Charles F. Royal. F: dison. Edward Kuli & Ernest F. Smith. Medv.: Herman The Return Of Tarzan. Numa Pictures Corp. 1920. Brix, Ula Holt, Frank Baker, Don Costello, Le I : Harry Revier. Medv.: Gene Pollar, Karla wis Sargent, JaCk Mower. D-Prm: 1/8-1938. SChramm og Peggy Hamann. Tarzan Escapes. (Tarzan undslipper). MGM. 1936. The Son O f Tarzan. National Film Corp. 1921. I: I : RiChard Thorpe. M : Karl Brown & John V. Harry Revier & Arthur J. -

The Influence of Herman Melville's Moby-Dick on Cormac Mccarthy's Blood Meridian

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 8-1-2014 The Influence of Herman Melville's Moby-Dick on Cormac McCarthy's Blood Meridian Ryan Joseph Tesar University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Repository Citation Tesar, Ryan Joseph, "The Influence of Herman Melville's Moby-Dick on Cormac McCarthy's Blood Meridian" (2014). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 2218. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/6456449 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE INFLUENCE OF HERMAN MELVILLE’S MOBY-DICK ON CORMAC MCCARTHY’S BLOOD MERIDIAN by Ryan Joseph Tesar Bachelor of Arts in English University of Nevada, Las Vegas 2012 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts – English Department of English College of Liberal Arts The Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas August 2014 Copyright by Ryan Joseph Tesar, 2014 All Rights Reserved - THE GRADUATE COLLEGE We recommend the thesis prepared under our supervision by Ryan Joseph Tesar entitled The Influence of Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick on Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian is approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts - English Department of English John C. -

FILM Moby-Dick (1851) Herman Melville (1819-1891) Adaptation By

FILM Moby-Dick (1851) Herman Melville (1819-1891) adaptation by Ray Bradbury & John Huston (1956) ANALYSIS Moby-Dick is the greatest American novel. This is the only film adaptation that is faithful to the book. All other movie versions are ridiculous. The only improvement any of them has made over this adaptation is in special effects—more spectacular shots of the white whale underwater. These are entertaining to see, but they add nothing to understanding and actually distract from the meanings of the book. Movie critics have been especially stupid in responding to this film. Ray Bradbury is a discerning writer who is largely true to Melville and John Huston was the most literary director in Hollywood. Contrary to the critics, the casting is perfect—especially Gregory Peck as Captain Ahab. Queequeg is also brilliantly portrayed. Unlike their critics Bradbury and Huston display a deep knowledge of the book, although they are limited in how much of it they can present in a film. They are able to include significant lines of dialogue that are over the heads of movie critics, such as the Pequod as a symbol of the world, expressed when Orson Welles as Father Mapple dresses like a sea captain, preaches from a pulpit in the form of a ship’s prow and refers to everyone in the world as “Shipmates.” They also convey the pantheistic divinity of Moby-Dick, who seems to be everywhere in the world at once. As Pip says, “That a great white god.” They establish that the story is a psychological allegory when Ishmael says that the sea is a “mirror” of himself. -

570183Bk Son of Kong 15/7/07 7:50 PM Page 8

570185bk Treasure:570183bk Son of Kong 15/7/07 7:50 PM Page 8 John Morgan Widely regarded in film-music circles as a master colorist with a keen insight into orchestration and the power of music, Los Angeles-based composer John Morgan began his career working alongside such composers as Alex North and Fred Steiner before embarking on his own. Among other projects, he co-composed the richly dramatic score for the cult-documentary film Trinity and Beyond, described by one critic as “an atomic-age Fantasia, thanks to its spectacular nuclear explosions and powerhouse music.” In addition, Morgan has won acclaim for efforts to rescue, restore and re-record lost film scores from the past. His work can be found on the Naxos, Marco Polo, RCA and Tribune Film Classics labels. William Stromberg Besides his own film scores and his work conducting studio orchestras in Hollywood, William T. Stromberg is noted for his passion in reconstructing and conducting film scores from Hollywood’s Golden Age. For Naxos and Marco Polo he has conducted albums of music devoted to Max Steiner, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Alfred Newman, Philip Sainton, Bernard Herrmann and Franz Waxman. He has also conducted several albums devoted to concert works of American composers, including a second album of music by Ferde Grofé, featuring his Hollywood Suite and Hudson River Suite. He and longtime colleague John Morgan have collaborated on numerous film scores, ranging from Trinity and Beyond to Starship Troopers 2: Hero of the Federation. Moscow Symphony Orchestra Established in 1989, the Moscow Symphony Orchestra includes prize-winners and laureates of Russian and international music competitions and graduates of conservatories in Moscow, Leningrad and Kiev who have played under such conductors as Svetlanov, Rozhdestvensky, Mravinsky and Ozawa, in Russia and throughout the world. -

Dvds - Now on DVD, Glenda Farrell As Torchy Blane - Nytimes.Com 5/10/10 3:08 PM

DVDs - Now on DVD, Glenda Farrell as Torchy Blane - NYTimes.com 5/10/10 3:08 PM Welcome to TimesPeople TimesPeople recommended: Sex & Drugs & the Spill 3:08Recommend PM Get Started HOME PAGE TODAY'S PAPER VIDEO MOST POPULAR TIMES TOPICS Get Home Delivery Log In Register Now Search All NYTimes.com DVD WORLD U.S. N.Y. / REGION BUSINESS TECHNOLOGY SCIENCE HEALTH SPORTS OPINION ARTS STYLE TRAVEL JOBS REAL ESTATE AUTOS Search Movies, People and Showtimes by ZIP Code More in Movies » In Theaters The Critics' On DVD Tickets & Trailers Carpetbagger Picks Showtimes DVDS B-Movie Newshound: Hello, Big Boy, Get Me Rewrite! Warner Home Video Glenda Farrell with Tom Kennedy, left, and Barton MacLane in “Torchy Blane in Chinatown” (1939). By DAVE KEHR Published: May 7, 2010 SIGN IN TO RECOMMEND The Torchy Blane Collection TWITTER Enlarge This Image “B movie” is now SIGN IN TO E- a term routinely MAIL applied to PRINT essentially any SHARE low-budget, vaguely disreputable genre film. But it used to mean something quite specific. During the Great Depression MOST POPULAR exhibitors began offering double E-MAILED BLOGGED SEARCHED VIEWED MOVIES features in the hope of luring back their diminished audience. The 1. 10 Days in a Carry-On program would consist of an A picture, 2. Tell-All Generation Learns to Keep Things Offline with stars, conspicuous production 3. The Moral Life of Babies Shout! Factory and New Horizons Pictures 4. Paul Krugman: Sex & Drugs & the Spill Youth in revolt: P. J. Soles, center, values and a running time of 80 5. -

January 2020 the Lighthouse Robert Eggers the Irish Film Institute

JANUARY 2020 THE LIGHTHOUSE ROBERT EGGERS THE IRISH FILM INSTITUTE The Irish Film Institute is Ireland’s EXHIBIT national cultural institution for film. It aims to exhibit the finest in independent, Irish and international cinema, preserve PRESERVE Ireland’s moving image heritage at the Irish Film Archive, and encourage EDUCATE engagement with film through its various educational programmes. THE NIGHT WINTER MENU OF IDEAS 2020 Fancy some healthy and hearty food this January? Look The Night of Ideas is a worldwide initiative, spearheaded by no further than the IFI Café Bar’s delicious winter menu, Institut Français, that celebrates the constant stream of ideas featuring new dishes including Wicklow Lamb Stew, between countries, cultures, and generations. The IFI and Vegetarian Lasagne, and Warm Winter Veg with Harissa the French Embassy are proud to present this third edition in Yoghurt and Beetroot Crisps. Book your table by emailing Ireland, the theme of which is ‘Being Alive’. For more details on [email protected] or by ringing 01-6798712. the event, please see page 15. NAME YOUR SEAT COMING SOON Parasite Naming a seat in the newly refurbished Cinema 1 is a Coming to the IFI in February are two of the year’s most fantastic way to demonstrate your own passion for film, anticipated new releases: Bong Joon Ho’s Parasite, winner of celebrate the memory of someone who loved the IFI, or the 2019 Palme d’Or and hotly tipped for Oscar glory, follows the gift a unique birthday or anniversary present to the film sinister relationship between an unemployed family and their fan in your life! The only limit is 50 characters and your patrons; and Céline Sciamma’s stunning Portrait of a Lady on Fire, imagination. -

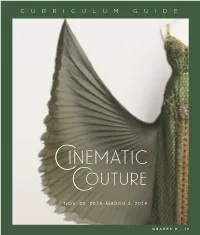

C U R R I C U L U M G U I

C U R R I C U L U M G U I D E NOV. 20, 2018–MARCH 3, 2019 GRADES 9 – 12 Inside cover: From left to right: Jenny Beavan design for Drew Barrymore in Ever After, 1998; Costume design by Jenny Beavan for Anjelica Huston in Ever After, 1998. See pages 14–15 for image credits. ABOUT THE EXHIBITION SCAD FASH Museum of Fashion + Film presents Cinematic The garments in this exhibition come from the more than Couture, an exhibition focusing on the art of costume 100,000 costumes and accessories created by the British design through the lens of movies and popular culture. costumer Cosprop. Founded in 1965 by award-winning More than 50 costumes created by the world-renowned costume designer John Bright, the company specializes London firm Cosprop deliver an intimate look at garments in costumes for film, television and theater, and employs a and millinery that set the scene, provide personality to staff of 40 experts in designing, tailoring, cutting, fitting, characters and establish authenticity in period pictures. millinery, jewelry-making and repair, dyeing and printing. Cosprop maintains an extensive library of original garments The films represented in the exhibition depict five centuries used as source material, ensuring that all productions are of history, drama, comedy and adventure through period historically accurate. costumes worn by stars such as Meryl Streep, Colin Firth, Drew Barrymore, Keira Knightley, Nicole Kidman and Kate Since 1987, when the Academy Award for Best Costume Winslet. Cinematic Couture showcases costumes from 24 Design was awarded to Bright and fellow costume designer acclaimed motion pictures, including Academy Award winners Jenny Beavan for A Room with a View, the company has and nominees Titanic, Sense and Sensibility, Out of Africa, The supplied costumes for 61 nominated films.