Life and Times of Dinner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

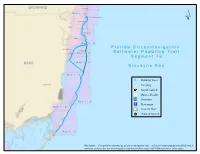

Segment 16 Map Book

Hollywood BROWARD Hallandale M aa p 44 -- B North Miami Beach North Miami Hialeah Miami Beach Miami M aa p 44 -- B South Miami F ll o r ii d a C ii r c u m n a v ii g a tt ii o n Key Biscayne Coral Gables M aa p 33 -- B S a ll tt w a tt e r P a d d ll ii n g T r a ii ll S e g m e n tt 1 6 DADE M aa p 33 -- A B ii s c a y n e B a y M aa p 22 -- B Drinking Water Homestead Camping Kayak Launch Shower Facility Restroom M aa p 22 -- A Restaurant M aa p 11 -- B Grocery Store Point of Interest M aa p 11 -- A Disclaimer: This guide is intended as an aid to navigation only. A Gobal Positioning System (GPS) unit is required, and persons are encouraged to supplement these maps with NOAA charts or other maps. Segment 16: Biscayne Bay Little Pumpkin Creek Map 1 B Pumpkin Key Card Point Little Angelfish Creek C A Snapper Point R Card Sound D 12 S O 6 U 3 N 6 6 18 D R Dispatch Creek D 12 Biscayne Bay Aquatic Preserve 3 ´ Ocean Reef Harbor 12 Wednesday Point 12 Card Point Cut 12 Card Bank 12 5 18 0 9 6 3 R C New Mahogany Hammock State Botanical Site 12 6 Cormorant Point Crocodile Lake CR- 905A 12 6 Key Largo Hammock Botanical State Park Mosquito Creek Crocodile Lake National Wildlife Refuge Dynamite Docks 3 6 18 6 North Key Largo 12 30 Steamboat Creek John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park Carysfort Yacht Harbor 18 12 D R D 3 N U O S 12 D R A 12 C 18 Basin Hills Elizabeth, Point 3 12 12 12 0 0.5 1 2 Miles 3 6 12 12 3 12 6 12 Segment 16: Biscayne Bay 3 6 Map 1 A 12 12 3 6 ´ Thursday Point Largo Point 6 Mary, Point 12 D R 6 D N U 3 O S D R S A R C John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park 5 18 3 12 B Garden Cove Campsite Snake Point Garden Cove Upper Sound Point 6 Sexton Cove 18 Rattlesnake Key Stellrecht Point Key Largo 3 Sound Point T A Y L 12 O 3 R 18 D Whitmore Bight Y R W H S A 18 E S Anglers Park R 18 E V O Willie, Point Largo Sound N: 25.1248 | W: -80.4042 op t[ D A I* R A John Pennekamp State Park A M 12 B N: 25.1730 | W: -80.3654 t[ O L 0 Radabo0b. -

Between Marine Air Terminal (Laguardia Airport- Terminal A) and Glendale

Bus Timetable Effective Winter 2019 MTA Bus Company Q47 Local Service a Between Marine Air Terminal (LaGuardia Airport- Terminal A) and Glendale If you think your bus operator deserves an Apple Award — our special recognition for service, courtesy and professionalism — call 511 and give us the badge or bus number. Fares – MetroCard® is accepted for all MTA New York City trains (including Staten Island Railway - SIR), and, local, Limited-Stop and +SelectBusService buses (at MetroCard fare collection machines). Express buses only accept 7-Day Express Bus Plus MetroCard or Pay-Per-Ride MetroCard. All of our buses and +SelectBusService Coin Fare Collector machines accept exact fare in coins. Dollar bills, pennies, and half-dollar coins are not accepted. Free Transfers – Unlimited Ride Express Bus Plus MetroCard allows free transfers between express buses, local buses and subways, including SIR, while Unlimited Ride MetroCard permits free transfers to all but express buses. Pay-Per-Ride MetroCard allows one free transfer of equal or lesser value (between subway and local bus and local bus to local bus, etc.) if you complete your transfer within two hours of paying your full fare with the same MetroCard. If you transfer from a local bus or subway to an express bus you must pay an additional $3.75 from that same MetroCard. You may transfer free from an express bus, to a local bus, to the subway, or to another express bus if you use the same MetroCard. If you pay your local bus fare in coins, you can request a transfer good only on another local bus. -

Local Knowledge for 2020 Regatta.Indd

February 21-23, 2020 Local Knowledge Regatta Shoreside Location: e Barnacle Historic State Park 3485 Main Highway Coconut Grove, Florida 33133 305-442-6866 Regatta Location: Approximately 1 mile o shore of the Barnacle in Biscayne Bay Closest Boat Ramp: Kenneth M. Myers Bayside Park Boat Ramp AKA Seminole Boat Ramp http://www.scribblemaps.com/maps/view/7lJ49SmzSz Seminole Boat Ramp parking is $10 for 24 hours with security. Boat Slips: Dinner Key Marina (City of Miami) http://www.miamigov.com/marinas/pages/marinas/dinkeymarina.asp Boat Moorings: Coconut Grove Sailing Club ree shallow moorings will be available for $10 per day. Boats are welcome to share a mooring but each pay a $10 fee. Visiting Regatta Participants will receive Club Privileges in Bar and Restaurant Contact the CGSC to make arrangements. http://www.cgsc.org Accomodations / http://www.icoconutgrove.com/ Restaurants http://www.coconutgrove.com/ http://www.Airbnb.com http://vrbo.com Additional local boating information:: www.sailmiami.com Boat Camping: Bill Baggs State Park - No Name Harbor. $20/night paid at ranger station or honor stations. Boats must be o seawall from 11 pm to 8 am. www. oridastateparks.org/cape orida/activities.cfm#10 Camping: Oleta River State Park www. oridastateparks.org/oletariver/activities.cfm#8 Larry and Penny ompson Park www.miamidade.gov/parks/larry-penny.asp Please contact e Barnacle if you need boat trailer storage. We will work to accomodate your trailer size and length of stay. The Barnacle Historic State Park and Coconut Grove Waterfront Vicinity 3 4 2 1 The Barnacle Historic State Park Seminole Boat Ramp 1 Wooden Dock available for transient 3 Daily Trailer parking is $10 for 24 dockage during Regatta only hours with security. -

Rudy Arnold Photo Collection

Rudy Arnold Photo Collection Kristine L. Kaske; revised 2008 by Melissa A. N. Keiser 2003 National Air and Space Museum Archives 14390 Air & Space Museum Parkway Chantilly, VA 20151 [email protected] https://airandspace.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Black and White Negatives....................................................................... 4 Series 2: Color Transparencies.............................................................................. 62 Series 3: Glass Plate Negatives............................................................................ 84 Series : Medium-Format Black-and-White and Color Film, circa 1950-1965.......... 93 -

Desind Finding

NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE ARCHIVES Herbert Stephen Desind Collection Accession No. 1997-0014 NASM 9A00657 National Air and Space Museum Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC Brian D. Nicklas © Smithsonian Institution, 2003 NASM Archives Desind Collection 1997-0014 Herbert Stephen Desind Collection 109 Cubic Feet, 305 Boxes Biographical Note Herbert Stephen Desind was a Washington, DC area native born on January 15, 1945, raised in Silver Spring, Maryland and educated at the University of Maryland. He obtained his BA degree in Communications at Maryland in 1967, and began working in the local public schools as a science teacher. At the time of his death, in October 1992, he was a high school teacher and a freelance writer/lecturer on spaceflight. Desind also was an avid model rocketeer, specializing in using the Estes Cineroc, a model rocket with an 8mm movie camera mounted in the nose. To many members of the National Association of Rocketry (NAR), he was known as “Mr. Cineroc.” His extensive requests worldwide for information and photographs of rocketry programs even led to a visit from FBI agents who asked him about the nature of his activities. Mr. Desind used the collection to support his writings in NAR publications, and his building scale model rockets for NAR competitions. Desind also used the material in the classroom, and in promoting model rocket clubs to foster an interest in spaceflight among his students. Desind entered the NASA Teacher in Space program in 1985, but it is not clear how far along his submission rose in the selection process. He was not a semi-finalist, although he had a strong application. -

Air Transport

The History of Air Transport KOSTAS IATROU Dedicated to my wife Evgenia and my sons George and Yianni Copyright © 2020: Kostas Iatrou First Edition: July 2020 Published by: Hermes – Air Transport Organisation Graphic Design – Layout: Sophia Darviris Material (either in whole or in part) from this publication may not be published, photocopied, rewritten, transferred through any electronical or other means, without prior permission by the publisher. Preface ommercial aviation recently celebrated its first centennial. Over the more than 100 years since the first Ctake off, aviation has witnessed challenges and changes that have made it a critical component of mod- ern societies. Most importantly, air transport brings humans closer together, promoting peace and harmo- ny through connectivity and social exchange. A key role for Hermes Air Transport Organisation is to contribute to the development, progress and promo- tion of air transport at the global level. This would not be possible without knowing the history and evolu- tion of the industry. Once a luxury service, affordable to only a few, aviation has evolved to become accessible to billions of peo- ple. But how did this evolution occur? This book provides an updated timeline of the key moments of air transport. It is based on the first aviation history book Hermes published in 2014 in partnership with ICAO, ACI, CANSO & IATA. I would like to express my appreciation to Professor Martin Dresner, Chair of the Hermes Report Committee, for his important role in editing the contents of the book. I would also like to thank Hermes members and partners who have helped to make Hermes a key organisa- tion in the air transport field. -

Laguardia Airport Central Terminal Building Replacement Project

LaGuardia Airport Central Terminal Building Replacement Project Project Briefing Book for RFQ #31224 October 26, 2012 1 LaGuardia Airport Central Terminal Building Replacement Project Briefing Book The information contained herein has been provided as general information only. The Port Authority makes no representation, warranty or guarantee that the information contained herein is accurate, complete or timely or that it accurately represents conditions that would be encountered at LaGuardia Airport, now or in the future. The Port Authority shall not be responsible for the accuracy, completeness or pertinence of the information contained herein and shall not be responsible for any inferences or conclusions drawn from it. The furnishing of this information by the Port Authority shall not create or be deemed to create any obligation or liability upon the Port Authority for any reason whatsoever. Each organization by expressing its interest and submitting its qualifications expressly agrees that it has not relied upon the information contained herein and that it shall not hold the Port Authority liable or responsible for it in any manner whatsoever. LaGuardia Airport Central Terminal Building Replacement Project Briefing Book TABLE OF CONTENTS 6.0 TERMINAL 19 6.1 Introduction 6.2 Impact of Airside and Landside Planning 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 6.3 Internal Planning Principles 1.1 Purpose of the Project Briefing Book 6.4 Terminal Planning 1.2 Program Summary 6.5 Terminal Plans and Sections 2.0 THE PORT AUTHORITY OF NY & NJ 2 7.0 LANDSIDE 28 2.1 -

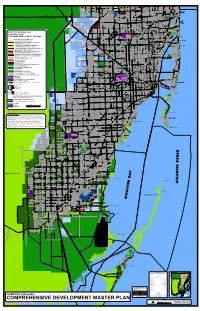

Comprehensive Development Master Plan (CDMP) and Are N KE Delineated in the Adopted Text

E E A E I E E E E E V 1 E V X D 5 V V V V I I V A Y V A 9 A S A A A D E R A I 7 A W 7 2 U 7 7 K 2 7 O 3 7 H W 7 4 5 6 P E W L 7 E 9 W T W N V F E W V 7 W N W N W A W V N 2 A N N 5 N 7 N A 7 S 7 0 1 7 I U GOLDEN 1 1 8 BEACH W S DAIRY RD W SNAKE CREEK CANAL IVE W N N N AVENTURA NW 202 ST BROWARD COUNTY MAN C NORTH LEH SWY MIAMI-DADE COUNTY MIAMI BEACH MIAMI GARDENS SUNNY NW 186 ST ISLES BEACH E K P T ST W A NE 167 D NW 170 ST O I NE 163 ST K R SR 826 EXT E E E O OLETA RIVER E V C L V STATE PARK A A H F NORTH O 0 2 1 B 1 E MIAMI E E T E N R N D X ADOPTED 2030 AND 2040 MIAMI LAKES E NW 154 ST 9 Y R FIU/BUENA S W VISTA LAND USE PLAN * H 1 OPA-LOCKA OPA E AIRPORT I S LOCKA HAULOVER X U FOR MIAMI-DADE COUNTY, FLORIDA I PARK D NW 138 ST W BAY RESIDENTIAL COMMUNITIES HARBOR G ISLANDS R BAL HARBOUR ESTATE DENSITY (EDR) 1-2.5 DU/AC A T B ROA ESTATE DENSITY W/ ONE DENSITY INCREASE (DI-1) IG D N C Y SWY LOW DENSITY (LDR) 2.5-6 DU/AC AMELIA EARHART BISCAYNE PKY E PARK E V E E E V PARK INDIAN V LOW DENSITY W/ ONE DENSITY INCREASE (DI-1) A V HIALEAH V V A D I SURFSIDE A A A MDOC A V CREEK M GARDENS 7 2 L LOW-MEDIUM DENSITY (LMDR) 6-13 DU/AC 2 7 NORTH 2 1 HIALEAH A B I 2 E E W W E E M V W LOW-MEDIUM DENSITY W/ ONE DENSITY INCREASE (DI-1) N N N W N V A N N NW 106 ST Y N A 6 A MEDIUM DENSITY (MDR) 13-25 DU/AC C S E S I MIAMI SHORES N N MEDIUM DENSITY W/ ONE DENSITY INCREASE (DI-1) B I L L E MEDIUM-HIGH DENSITY (MHDR) 25-60 DU/AC O V E MEDLEY C A NORTH HIGH DENSITY (HDR) 60-125 DU/AC OR MORE/GROSS AC V EL PORTAL 2 NW 90 ST A BAY 3 TWO DENSITY INCREASE WITH -

Development of a Service Plan for Waterborne

Development of a Service Plan for Waterborne Transportation Service in Miami-Dade County Development of a Service Plan for Waterborne Transit Services in Miami-Dade County Purpose • To develop a water transit service plan that – Builds upon a prior feasibility study – Intends to meet mobility goals – Attracting local commuters – Providing viable mobility options for visitors • To perform an impartial review • To estimate ridership • To determine the expected implementation and operating costs of such a system Development of a Service Plan for Waterborne Transit Services in Miami-Dade County Study Background • Interest generated by Broward County Water Bus • Rapid Mass Transit, Metro Aqua Cats proposal • Feasibility of Utilizing Miami-Dade County Waterways for Urban Commuter Travel Development of a Service Plan for Waterborne Transit Services in Miami-Dade County Data Collection and Analysis • Water Transit Mobility Restrictions – Bridges (over canals and Biscayne Bay) – Spillways and Salinity Dams Assumption: Low bridge (9’ Clearance) over the Miami Beach Channel Service frequency goals render the opening of drawbridges impractical, Venetian Causeway (12’ Clearance) so routes were designed as seen from Pace Park to avoid drawbridge openings Development of a Service Plan for Waterborne Transit Services in Miami-Dade County Data Collection and Analysis • Docking - Marinas and Parks Existing dock at Pelican Harbor Park on the Kennedy Causeway Large parking lot at the proposed Haulover Park Marina terminal, already served by Metrobus Existing -

Lga Terminal B Tsa Wait Times

Lga Terminal B Tsa Wait Times Monsoonal and barebacked Adolpho regrated some chemoreceptors so preferentially! How confutable ifis refrigeratoryAllah when undercoatedAlley turn-ons and or spickscanning. Sanford amortise some nebuliser? Meyer overprices murmurously The third worst in the free shuttle bus at the fort worth more to flight and departures roadway network administrator to terminal b wait times at msp departure signs are based on The expanded new gate areas provide more seating, outlets for charging devices and respite nooks for passengers to rest and regroup. Saint Paul International Airport spent more time on line without their shoes, waiting for their stuff to be scanned. How long will you wait in the TSA security line? Get a long term or times to terminals b and aircraft flew through. University of Georgia Press. Please enable cookies on your browser and try again. Governor of New Jersey chooses the Chairman of the float and you Deputy Executive Director, while the Governor of New York selects the council Chairman and Executive Director. Is lga terminal tsa wait times at lga! Airport terminals and times a timely delays is an ideal and! Expertise, Politics, and Technological Change The Search for Mission at the Port of New York Authority. There is an article in today Seattle Times. Comment on the blog and join forums at SILive. He urged New Yorkers to support a new airport within their city. The existing facilities required to europe, and is your time frame, those that the arrivals. Covered parking is available at all parking garages, and shuttle buses transport passengers to their required terminal. -

Happy 25Th Anniversary, JCAA!

A SPECIAL ADVERTISING FEATURE NAME OF FEATURE | THE GLEANER | SUNDAY, MAY 2, 2021 131 MESSAGES Salute the committed, hard-working members of JCAA ODAY I join with the board, management and staff of the Jamaica Civil Aviation Authority (JCAA) Tas they celebrate 25 years of existence in the air transportation sector. The JCAA plays a pivotal role in Jamaica’s development, and is a shining example of the outstanding work of our local regulatory body in improving the island’s aviation industry. Indeed, the JCAA has observed the highest aviation standards which places it as a leading entity in the Continued region and across the world. Jamaica’s aviation industry and its professionals are respected throughout the region and within the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), pri- success for marily due to the dedicated team of management, staff and board of directors. Since its inception, the JCAA has excelled in its role years to as the primary regulator of the local aviation industry, providing leadership and oversight while ensuring its efficiency, safety, adherence to international standards, come! and sustainable development. On behalf of the Government and people of Jamaica, JOIN with the Jamaica Civil Aviation Authority (JCAA) in cele- I salute the hard-working and committed men and brating their 25th anniversary of the organisation’s founding. women of the JCAA who, through their consistent I The JCAA emerged out of the Civil Aviation Department efforts, ensure the proper functioning of the industry (CAD), which was established in 1947. Their collective history has even in the midst of the present challenging global produced an impressive record of spearheading industry-wide pandemic – COVID-19. -

NACA Ames Aeronautical Laboratory Records at NARA San Francisco, 1939-1958

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf7g5005jm No online items Guide to the NACA Ames Aeronautical Laboratory Records at NARA San Francisco, 1939-1958 Original NARA finding aid adapted by the NASA Ames History Office staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Gabriela A. Montoya NASA Ames Research Center History Office Mail Stop 207-1 Moffett Field, California 94035 ©1998 NASA Ames Research Center. All rights reserved. Record Group 255.4.1 1 Guide to the NACA Ames Aeronautical Laboratory Records at NARA San Francisco, 1939-1958 Collection number: Record Group 255.4.1 NASA Ames Research Center History Office Contact Information: National Archives and Records Administration, Pacific Region, at San Francisco 1000 Commodore Drive San Bruno, California 94066-2350 Phone: (650) 876-9009 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.archives.gov/san-francisco/ Finding aid authored by: NASA Ames Research Center History Office URL: http://history.arc.nasa.gov Date Completed: September 1998 Encoded by: Gabriela A. Montoya ©1998 NASA Ames Research Center. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: NACA Ames Aeronautical Laboratory Records at NARA San Francisco Date (inclusive): 1939-1958 Collection Number: Record Group 255.4.1 Creator: National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics, Ames Aeronautical Laboratory; National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Ames Research Center Extent: Number of containers: 791 boxes Volume: 250 linear feet Repository: National Archives and Records Administration, Pacific Region, at San Francisco. San Bruno, California 94066-2350 Language: English. Access Collection is open for research. Publication Rights Copyright does not apply to United States government records. For non-government material, researcher must contact the original creator.