Lives on Hold Making Sure No Child Is Left Behind in Myanmar LIVES on HOLD UNICEF – CHILD ALERT MAY 2017 2 MAKING SURE NO CHILD IS LEFT BEHIND in MYANMAR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BURMA (MYANMAR) COUNTRY of ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service

BURMA (MYANMAR) COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service 17 June 2011 BURMA (MYANMAR) 17 JUNE 2011 Contents Preface Latest News EVENTS IN BURMA FROM 16 MAY TO 17 JUNE 2011 Useful news sources for further information REPORTS ON BURMA PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED BETWEEN 16 MAY AND 17 JUNE 2011 Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................ 1.01 Map ........................................................................................................................ 1.07 2. ECONOMY ................................................................................................................ 2.01 3. HISTORY (INDEPENDENCE (1948) – NOVEMBER 2010) ................................................ 3.01 Constitutional referendum – 2008....................................................................... 3.03 Build up to 2010 elections ................................................................................... 3.05 4. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS (NOVEMBER 2010 – MARCH 2011)....................................... 4.01 November 2010 elections .................................................................................... 4.01 Release of Aung San Suu Kyi ............................................................................. 4.13 Opening of Parliament ......................................................................................... 4.16 5. CONSTITUTION......................................................................................................... -

Ethnic Armed Actors and Justice Provision in Myanmar

Ethnic Armed Actors and Justice Provision in Myanmar Brian McCartan and Kim Jolliffe October 2016 Preface As a result of decades of ongoing civil war, large areas of Myanmar remain outside government rule, or are subject to mixed control and governance by the government and an array of ethnic armed actors (EAAs). These included ethnic armed organizations, with ceasefires or in conflict with the state, as well as state-backed ethnic paramilitary organizations, such as the Border Guard Forces and People’s Militia Forces. Despite this complexity, order has been created in these areas, in large part through customary justice mechanisms at the community level, and as a result of justice systems administered by EAAs. Though the rule of law and the workings of Myanmar’s justice system are receiving increasing attention, the role and structure of EAA justice systems and village justice remain little known and therefore, poorly understood. As such, The Asia Foundation is pleased to present this research on justice provision and ethnic armed actors in Myanmar, as part of the Foundation’s Social Services in Contested Areas in Myanmar series. The study details how the village, and village-based mechanisms, are the foundation of stability and order for civilians in most of these areas. These systems have then been built through EAA justice systems, which maintain a hierarchy of courts above the village level. Understanding the continuity and stability of these village systems, and the heterogeneity of the EAA justice systems which work alongside them, is essential for understanding civilians’ experiences of justice and security across Myanmar, as well as the opportunities for positive change that exist in Myanmar’s ongoing peace process and governance reforms. -

Sold to Be Soldiers the Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers in Burma

October 2007 Volume 19, No. 15(C) Sold to be Soldiers The Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers in Burma Map of Burma........................................................................................................... 1 Terminology and Abbreviations................................................................................2 I. Summary...............................................................................................................5 The Government of Burma’s Armed Forces: The Tatmadaw ..................................6 Government Failure to Address Child Recruitment ...............................................9 Non-state Armed Groups....................................................................................11 The Local and International Response ............................................................... 12 II. Recommendations ............................................................................................. 14 To the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) ........................................ 14 To All Non-state Armed Groups.......................................................................... 17 To the Governments of Thailand, Laos, Bangladesh, India, and China ............... 18 To the Government of Thailand.......................................................................... 18 To the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)....................... 18 To UNICEF ........................................................................................................ -

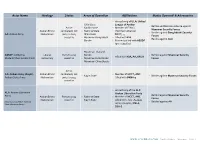

ACLED – Myanmar Conflict Update – Table 1

Actor Name Ideology Status Areas of Operation Affiliations Modus Operandi & Adversaries - Armed wing of ULA: United - Chin State League of Arakan - Battles and Remote violence against Active - Kachin State - Member of FPNCC Myanmar Security Forces Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Rakhine State (Northern Alliance) - Battles against Bangladeshi Security AA: Arakan Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Shan State - NCCT, , , Forces ceasefire - Myanmar-Bangladesh - Allied with KIA - Battles against ALA Border - Formerly allied with ABSDF (pre-ceasefire) - Myanmar-Thailand ABSDF: All Burma Liberal Party to 2015 Border - Battled against Myanmar Security - Allied with KIA, AA, KNLA Students’ Democratic Front democracy ceasefire - Myanmar-India Border Forces - Myanmar-China Border Active AA: Arakan Army (Kayin): Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Member of NCCT, ANC - Kayin State - Battles against Myanmar Security Forces Arakan State Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Allied with DKBA-5 ceasefire - Armed wing of the ALP: ALA: Arakan Liberation Arakan Liberation Party - Battled against Myanmar Security Army Arakan Ethnic Party to 2015 - Rakhine State - Member of NCCT, ANC Forces Nationalism ceasefire - Kayin State - Allied with AA: Arakan (Also known as RSLP: Rakhine - Battled against AA State Liberation Party) Army (Kayin), KNLA, SSA-S WWW.ACLEDDATA.COM | Conflict Update – Myanmar – Table 1 Rohingya Ethnic Active ARSA: Arakan Rohingya - Rakhine State Nationalism; combatant; not Salvation Army - Myanmar-Bangladesh UNKNOWN - Battles against Myanmar Security -

No More Denial: Children Affected by Armed Conflict in Myanmar (Burma)

No More Denial: Children Affected by Armed Conflict in Myanmar (Burma) May 2009 Watchlist Mission Statement The Watchlist on Children and Armed Conflict strives to end violations against children in armed conflicts and to guarantee their rights. As a global network, Watchlist builds partnerships among local, national and international nongovernmental organizations, enhancing mutual capacities and strengths. Working together, we strategically collect and disseminate information on violations against children in conflicts in order to influence key decision-makers to create and implement programs and policies that effectively protect children. Watchlist works within the framework of the provisions adopted in Security Council Resolutions 1261, 1314, 1379, 1460, 1539 and 1612, the principles of the Convention on the Rights of the Child and its protocols and other internationally adopted human rights and humanitarian standards. General supervision of Watchlist is provided by a Steering Committee of international nongovernmental organizations known for their work with children and human rights. The views presented in this report do not represent the views of any one organization in the network or the Steering Committee. For further information about Watchlist or specific reports, or to share information about children in a particular conflict situation, please contact: [email protected] www.watchlist.org Photo Credits Cover Photo: UNICEF/NYHQ2006- 1870/Robert Few Please Note: The people represented in the photos in this report are not necessarily themselves victims or survivors of human rights violations or other abuses. No More Denial: Children Affected by Armed Conflict in Myanmar (Burma) May 2009 Notes on Methodology . Information contained in this report is current through January 1, 2009. -

The Environmental Effects of Forced Displacement in Burma's Karenni State

1 The Environmental Effects of Forced Displacement in Burma's Karenni State Brandon MacDonald Student Number: 996 401 086 B.Sc. International Developmental Studies Co-op email: [email protected] Thesis Supervisor: Professor M. Isaac Personnel Number: 1042359 Department of Physical and Environmental Sciences & International Developmental Studies email: [email protected] Submission Date: April 18, 2012 2 Acknowledgements This thesis was a collaborative eFfort. My co-workers at Karenni Evergreen stimulated and challenged my thinking on issues surrounding the displacement of the Karenni people and the impact that this has had on environmental issues. They helped me find direction in my research and guided my data gathering process. They played an integral role in identifying the participants for my research. I am especially indebted to my good friend, roommate and co- worker Khu Kyi Reh who acted as a translator during many of the interviews. The participants gave generously of their time and their thoughts. Throughout this process Professor Marney Isaac was an engaged and thoughtful supporter. I am grateful for her input through both the research and the writing phases of this thesis. Lastly, I wish to acknowledge the help of my good friend Taskin Shiraze and my parents for their feedback on my written work. 3 Table of Contents List of Acronyms ............................................................................................................... 4 Abstract ............................................................................................................................. -

Child Soldiers in Myanmar: Role of Myanmar Government and Limitations of International Law

Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs Volume 6 Issue 1 June 2018 Child Soldiers in Myanmar: Role of Myanmar Government and Limitations of International Law Prajakta Gupte Follow this and additional works at: https://elibrary.law.psu.edu/jlia Part of the International and Area Studies Commons, International Law Commons, International Trade Law Commons, and the Law and Politics Commons ISSN: 2168-7951 Recommended Citation Prajakta Gupte, Child Soldiers in Myanmar: Role of Myanmar Government and Limitations of International Law, 6 PENN. ST. J.L. & INT'L AFF. (2018). Available at: https://elibrary.law.psu.edu/jlia/vol6/iss1/15 The Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs is a joint publication of Penn State’s School of Law and School of International Affairs. Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs 2018 VOLUME 6 NO. 1 CHILD SOLDIERS IN MYANMAR: ROLE OF MYANMAR GOVERNMENT AND LIMITATIONS OF INTERNATIONAL LAW Prajakta Gupte* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... 372 II. BACKGROUND AND HISTORY .................................................... 374 A. Major Political Actors ......................................................... 374 B. Definitions ............................................................................ 376 C. Development of Myanmar’s Society ................................. 377 III. ANALYSIS ...................................................................................... 382 A. Political Stability .................................................................. -

Report of the Secretary-General on Children and Armed Conflict in Myanmar

United Nations S/2017/1099 Security Council Distr.: General 22 December 2017 Original: English Report of the Secretary-General on children and armed conflict in Myanmar Summary The present report, submitted pursuant to Security Council resolution 1612 (2005) and subsequent resolutions, covers the period from 1 February 2013 to 30 June 2017 and is the fourth report on children and armed conflict in Myanmar to be submitted to the Security Council and its Working Group on Children and Armed Conflict. The report provides information on grave violations against children in Myanmar and identifies parties to the conflict responsible for such violations. During the reporting period, armed clashes in conflict-affected areas of the country continued to put children at risk and the country task force on monitoring and reporting documented and verified grave violations against children by the Myanmar Armed Forces (Tatmadaw) and other parties to the conflict, including all seven armed groups listed in the annual report of the Secretary-General on children and armed conflict. Grave violations against children increased in some areas owing to military operations and intensified clashes in several areas of the country, notably in Shan, Kachin and Rakhine States. Following the signing of a Joint Action Plan to end and prevent the recruitment and use of children by the Tatmadaw between the Government of Myanmar and the United Nations in June 2012, more than 849 children were released from the ranks of the Myanmar Armed Forces. Progress towards the implementation of the Joint Action Plan resulted in an annual decrease in the number of verified child recruitment cases. -

Non-State Armed Groups in the Myanmar Peace Process: What Are the Future Options?

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Kyed, Helene Maria; Gravers, Mikael Working Paper Non-state armed groups in the Myanmar peace process: What are the future options? DIIS Working Paper, No. 2014:07 Provided in Cooperation with: Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS), Copenhagen Suggested Citation: Kyed, Helene Maria; Gravers, Mikael (2014) : Non-state armed groups in the Myanmar peace process: What are the future options?, DIIS Working Paper, No. 2014:07, ISBN 978-87-7605-702-2, Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS), Copenhagen This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/122295 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten -

Monland Restoration Army

ANALYSIS PREFACE The Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Treaty (APMBT), signed in Ottawa in 1997, intends to eliminate a whole class of conventional weapons. The fact that over 140 countries have consented to be bound by the Treaty constitutes a remarkable achievement. The progress registered with the putting the Treaty into effect is of great credit to all those involved – governments, civil society and international organizations. Nevertheless, in some of the most seriously mine-affected countries progress has been delayed or even com- promised altogether by the fact that rebel groups that use anti-personnel mines do not consider themselves bound by the commitments of the government in power. Such groups, or non-state actors (NSAs), cannot them- selves become parties to an international Treaty, even if they are willing to agree to its terms. Faced with this potential “show-stopper”, Geneva Call came forward with a revolutionary new approach to engaging NSAs in committing themselves to the substance of the APMBT. Geneva Call designed a Deed of Commitment, to be deposited with the authorities of the Republic and Canton of Geneva, which NSAs can formally adhere to. This Deed of Commitment contains the same obligations as the APMBT. It allows the lead- ers of rebel groups to assume formal obligations and to accept that their performance in implementing those obligations will be monitored by an international body. The success of this approach is illustrated by the case of Sudan. In October 2001, the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A) agreed to give up their AP mines and signed the Deed of Commitment. -

Non-State Armed Groups in the Myanmar Peace Process: What Are the Future Options? Helene Maria Kyed and Mikael Gravers

DIIS WORKINGDIIS WORKING PAPER 2014:07PAPER Non-State Armed Groups in the Myanmar Peace Process: What are the Future Options? Helene Maria Kyed and Mikael Gravers DIIS Working Paper 2014:07 WORKING PAPER WORKING 1 DIIS WORKING PAPER 2014:07 HELENE MARIA KYED Seniorforsker, forskningsområdet Fred, Risiko & Vold, DIIS [email protected] MIKAEL GRAVERS Lektor i antropologi, Aarhus Universitet [email protected] DIIS Working Papers make available DIIS researchers’ and DIIS project partners’ work in progress towards proper publishing. They may include important documentation which is not necessarily published elsewhere. DIIS Working Papers are published under the responsibility of the author alone. DIIS Working Papers should not be quoted without the express permission of the author. DIIS WORKING PAPER 2014:07 © The authors and DIIS, Copenhagen 2014 DIIS • Danish Institute for International Studies Østbanegade 117, DK-2100, Copenhagen, Denmark Ph: +45 32 69 87 87 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.diis.dk Layout: Allan Lind Jørgensen Printed in Denmark by Vesterkopi AS ISBN: 978-87-7605-701-5 (print) ISBN: 978-87-7605-702-2 (pdf) Price: DKK 25.00 (VAT included) DIIS publications can be downloaded free of charge from www.diis.dk 2 DIIS WORKING PAPER 2014:07 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract 5 Introduction 7 The armed conflict in Myanmar – in brief 9 Colonialism and the ensuing ethnic divide 9 Conflicts after Independence and previous ceasefires 10 The ethnic NSAGs: The examples of Karen and Mon 12 The Karen 13 The Mon 15 The challenging peace negotiations (2012–2014) -

Armed Non-State Actors and Landmines Profiles

ANALYSIS PREFACE The Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Treaty (APMBT), signed in Ottawa in 1997, intends to eliminate a whole class of conventional weapons. The fact that over 140 countries have consented to be bound by the Treaty constitutes a remarkable achievement. The progress registered with the putting the Treaty into effect is of great credit to all those involved – governments, civil society and international organizations. Nevertheless, in some of the most seriously mine-affected countries progress has been delayed or even com- promised altogether by the fact that rebel groups that use anti-personnel mines do not consider themselves bound by the commitments of the government in power. Such groups, or non-state actors (NSAs), cannot them- selves become parties to an international Treaty, even if they are willing to agree to its terms. Faced with this potential “show-stopper”, Geneva Call came forward with a revolutionary new approach to engaging NSAs in committing themselves to the substance of the APMBT. Geneva Call designed a Deed of Commitment, to be deposited with the authorities of the Republic and Canton of Geneva, which NSAs can formally adhere to. This Deed of Commitment contains the same obligations as the APMBT. It allows the lead- ers of rebel groups to assume formal obligations and to accept that their performance in implementing those obligations will be monitored by an international body. The success of this approach is illustrated by the case of Sudan. In October 2001, the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A) agreed to give up their AP mines and signed the Deed of Commitment.