Re-Creating the Past: Building Historical Simulations with Hypermedia to Learn History. PUB DATE 2002-04-00 NOTE 23P.; Support Provided by the James S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Must Not Be Slavery

The “Spirit of Saratoga” must not be slavery Response to the repulsive wall of “lawn jockeys” that both glorify slavery and erase the history of Black jockeys, currently installed at the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame. This is not an act of vandalism. It is a work of public art and an act of applied art criticism. This work of protest art is in solidarity with the Art Action movement and the belief that art is essential to democracy We Reject the whitewashing of Saratoga’s history. We Reject the whitewashing of our national history. This nation was founded on slavery. So was the modern sport of Thoroughbred racing. You insult us and degrade the godfathers of the sport by perpetuating, profiting from and celebrating the flagrant symbol of servitude and slavery that is now called the “lawn jockey.” Just like the confederate flag, the “lawn jockey” is a celebrated relic of the antebellum era. The evolution of the hitching post (later renamed “lawn jockey”) follows the historical national trend of racist imagery and perpetuated stereotypes about Black Americans. This iconography is not unique, and the evidence can be found in everything from postcards, napkin holders, toothpaste, key racks, cigarette lighters, tobacco jars, syrup pitchers and doorstops, to name a fraction of the products designed to maintain the ideology of slavery. The original Jockeys were born into slavery or were the sons of slaves. From its inception in the early 19th century, African-American jockeys ruled the sport of organized Thoroughbred racing for almost a century. Isaac Murphy, the greatest American jockey of all time, was the son of a former slave. -

Can She Trust You Is a Live, Interactive

Recommended Grades: 3-8 Recommended Length: 40-50 minutes Presentation Overview: Can She Trust You is a live, interactive, distance learning program through which students will interact with the residents of the 1860 Ohio Village to help Rowena, a runaway slave who is searching for assistance along her way to freedom. Students will learn about each village resident, ask questions, and listen for clues. Their objective is to discover which resident is the Underground Railroad conductor and who Rowena can trust. Presentation Outcomes: After participating in this program, students will have a better understanding of the Underground Railroad, various viewpoints on the issue of slavery, and what life was like in the mid-1800s. Standards Connections: National Standards NCTE – ELA K-12.4 Students adjust their use of spoken, written, and visual language (e.g., conventions, style, vocabulary) to communicate effectively with a variety of audiences and for different purposes. NCTE – ELA K-12.12 Students use spoken, written, and visual language to accomplish their own purposes (e.g., for learning, enjoyment, persuasion, and the exchange of information). NCSS - SS.2 Time, Continuity, and Change NCSS - SS.5 Individuals, Groups, and Institutions NCSS - SS.6 Power, Authority, and Governance NCSS - SS.8 Science, Technology, and Society Ohio Revised Standards – Social Studies Grade Four Theme: Ohio in the United States Topic: Heritage Content Statement 7: Sectional issues divided the United States after the War of 1812. Ohio played a key role in these issues, particularly with the anti-slavery movement and the Underground Railroad. 1 Topic: Human Systems Content Statement 13: The population of the United States has changed over time, becoming more diverse (e.g., racial, ethnic, linguistic, religious). -

Northern Terminus: the African Canadian History Journal

orthern Terminus: N The African Canadian History Journal Mary “Granny” Taylor Born in the USA in about 1808, Taylor was a well-known Owen Sound vendor and pioneer supporter of the B.M.E. church. Vol. 17/ 2020 Northern Terminus: The African Canadian History Journal Vol. 17/ 2020 Northern Terminus 2020 This publication was enabled by volunteers. Special thanks to the authors for their time and effort. Brought to you by the Grey County Archives, as directed by the Northern Terminus Editorial Committee. This journal is a platform for the voices of the authors and the opinions expressed are their own. The goal of this annual journal is to provide readers with information about the historic Black community of Grey County. The focus is on historical events and people, and the wider national and international contexts that shaped Black history and presence in Grey County. Through essays, interviews and reviews, the journal highlights the work of area organizations, historians and published authors. © 2020 All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microreproduction, recording or otherwise – without prior written permission. For copies of the journal please contact the Archives at: Grey Roots: Museum & Archives 102599 Grey Road 18 RR#4 Owen Sound, ON N4K 5N6 [email protected] (519) 376-3690 x6113 or 1-877-473-9766 ISSN 1914-1297, Grey Roots Museum and Archives Editorial Committee: Karin Noble and Naomi Norquay Cover Image: “Owen Sound B. M. E. Church Monument to Pioneers’ Faith: Altar of Present Coloured Folk History of Congregation Goes Back Almost to Beginning of Little Village on the Sydenham When the Negros Met for Worship in Log Edifice, “Little Zion” – Anniversary Services Open on Sunday and Continue All Next Week.” Owen Sound Daily Sun Times, February 21, 1942. -

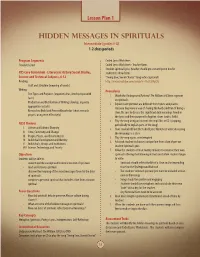

Hidden Messages in Spirituals Intermediate (Grades 6-8) 1-2 Class Periods

Lesson Plan 1 Hidden Messages in Spirituals Intermediate (grades 6-8) 1-2 class periods Program Segments Coded Lyrics Worksheet Freedom’s Land Coded Lyrics Worksheet - Teacher Notes Student Spiritual Lyrics (teacher should pre-cut and put in box for NYS Core Curriculum - Literacy in History/Social Studies, students to draw from) Science and Technical Subjects, 6-12 “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” Song video (optional) Reading http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Thz1zDAytzU • Craft and Structure (meaning of words) Writing Procedures • Test Types and Purposes (organize ideas, develop topic with 1. Watch the Underground Railroad: The William Still Story segment facts) on spirituals. • Production and Distribution of Writing (develop, organize 2. Explain how spirituals are different from hymns and psalms appropriate to task) because they were a way of sharing the hard condition of being a • Research to Build and Present Knowledge (short research slave. Be sure to discuss the significant dual meanings found in project, using term effectively) the lyrics and their purpose for fugitive slaves (codes, faith). 3. Play the song using an Internet site, mp3 file, or CD. (stopping NCSS Themes periodically to explain parts of the song) I. Culture and Cultural Diversity 4. Have students fill out the Coded Lyrics Worksheet while discussing II. Time, Continuity and Change the meanings as a class. III. People, Places, and Environments 5. Play the song again, uninterrupted. IV. Individual Development and Identity 6. Ask each student to choose a unique line from a box of pre-cut V. Individuals, Groups and Institutions VIII. Science, Technology, and Society Student Spiritual Lyrics. -

Slavery in New Jersey Lesson Plan

Elementary School | Grades 3–5 SLAVERY IN NEW JERSEY ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS What was the Underground Railroad and how did it help enslaved people gain their right of freedom? What role did the people of New Jersey play in the Underground Railroad and the struggle against slavery? OBJECTIVES Students will: → Describe the Underground Railroad and its significance in the abolition of chattel slavery. → Investigate Harriet Tubman’s role as a leader in the Underground Railroad. → Explore New Jersey’s role in the Underground Railroad and map key stops along the route. LEARNING STANDARDS See the standards alignment chart to learn how this lesson supports New Jersey State Standards. TIME NEEDED 45 minutes MATERIALS → AV equipment to show a video → On Track or Off the Rails? handout (one per student or one copy to read aloud) → On Track or Off the Rails Cards handout (copied and cut apart so each student gets one of each card) → Underground Railroad Routes in New Jersey handout (one per student or pair) → New Jersey Stops on the Underground Railroad handout (one per student) VOCABULARY abolitionist enslaver Quaker enslaved plantation Underground Railroad 72 Procedures 2 NOTE ABOUT LANGUAGE When discussing slavery with students, it is suggested the term “enslaved person” be used instead of “slave” to emphasize their humanity; that “enslaver” be used instead of “master” or “owner” to show that slavery was forced upon human beings; and that “freedom seeker” be used instead of “runaway” or “fugitive” to emphasize justice and avoid the connotation of lawbreaking. Write “Underground Railroad” on the board. Ask students if 1 they have ever heard this term and what they know about it. -

Organize Your Own: the Politics and Poetics of Self-Determination Movements © 2016 Soberscove Press and Contributing Authors and Artists

1 2 The Politics and Poetics of Self-determination Movements Curated by Daniel Tucker Catalog edited by Anthony Romero Soberscove Press Chicago 2016 Contents Acknowledgements 5 Gathering OURSELVES: A NOTE FROM THE Editor Anthony Romero 7 1 REFLECTIONS OYO: A Conclusion Daniel Tucker 10 Panthers, Patriots, and Poetries in Revolution Mark Nowak 26 Organize Your Own Temporality Rasheedah Phillips 48 Categorical Meditations Mariam Williams 55 On Amber Art Bettina Escauriza 59 Conditions Jen Hofer 64 Bobby Lee’s Hands Fred Moten 69 2 PANELS Organize Your Own? Asian Arts Initiative, Philadelphia 74 Organize Your Own? The Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago 93 Original Rainbow Coalition Slought Foundation, Philadelphia 107 Original Rainbow Coalition Columbia College, Chicago 129 Artists Talk The Leviton Gallery at Columbia College, Chicago 152 3 PROJECTS and CONTRIBUTIONS Amber Art and Design 170 Anne Braden Institute for Social Justice Research 172 Dan S. Wang 174 Dave Pabellon 178 Frank Sherlock 182 Irina Contreras 185 Keep Strong Magazine 188 Marissa Johnson-Valenzuela 192 Mary Patten 200 Matt Neff 204 Rashayla Marie Brown 206 Red76, Society Editions, and Hy Thurman 208 Robby Herbst 210 Rosten Woo 214 Salem Collo-Julin 218 The R. F. Kampfer Revolutionary Literature Archive 223 Thomas Graves and Jennifer Kidwell 225 Thread Makes Blanket 228 Works Progress with Jayanthi Kyle 230 4 CONTRIBUTORS, STAFF, ADVISORS 234 Acknowledgements Major support for Organize Your Own has been provided by The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage, with additional support from collaborating venues, including: the Averill and Bernard Leviton Gallery at Columbia College Chicago, Kelly Writers House’s Brodsky Gallery at the University of Pennsylvania, the Slought Foundation, the Asian Arts Initiative, the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, and others. -

THE POTOMAC FLYER a Publication of the Potomac Decoy Collectors Association

THE POTOMAC FLYER A Publication of the Potomac Decoy Collectors Association ISSUE # 101 SEPTEMBER 2008 Hi All, and welcome back from what I hope was a developed some new systems to make our treasury relaxing and enjoyable summer! There were several even more efficient! memorable auctions and shows these past few months, and I hope everyone was able to catch up with old Another change, the kind that’s most difficult to friends and add something special to their collection. accept, was the passing of founding member Ralph With the warm weather soon to be a distant memory Campbell. He was a great man and a great friend to so and the crisp air of fall right around the corner, we’re many of us in the club, and our thoughts and hearts about to hit another string of decoy shows, festivals continue to be with Barbara. To keep Ralph’s memory and auctions. So if you didn’t find anything to put on alive and to celebrate the qualities that made him such the shelf this summer, you’ll have plenty of a wonderful part of the decoy collecting community, I opportunities to do so soon enough. am proud to announce that beginning next year, the PDCA will bestow an annual award in his name. The And so we begin another year for the Potomac Decoy Ralph Campbell Memorial Award for Goodwill and Collectors Association. 2008 has certainly been a year Ambassadorship in the Decoy Collecting Community of great change for our club. After 11 years at the will recognize people who share Ralph’s passion for helm, founding president Tom East decided the time our hobby, his willingness to share all he knew about was right to hand things over to someone else. -

Lifetime in Jewelry Finish Talks by MATTHEW LEE and MARK THIESSE Associated Press ANCHORAGE, Alaska — Top U.S

Saturday, March 20, 2021 The Commercial Review Portland, Indiana 47371 www.thecr.com $1 U.S., China Lifetime in jewelry finish talks By MATTHEW LEE and MARK THIESSE Associated Press ANCHORAGE, Alaska — Top U.S. and Chinese offi - cials wrapped up two days of contentious talks in Alaska on Friday after trad - ing sharp and unusually public barbs over vastly dif - ferent views of each other and the world in their first face-to-face meeting since President Joe Biden took office. The two sides finished the meetings after an open - ing session in which they attacked each other in an unusually public way. The U.S. accused the Chinese delegation of “grandstand - ing” and Beijing fired back, saying there was a “strong smell of gunpowder and drama” that was entirely the fault of the Americans. The meetings in Anchor - age were a new test in increasingly troubled rela - tions between the two coun - tries, which are at odds over a range of issues from The Commercial Review/Bailey Cline trade to human rights in Tibet, Hong Kong and Jim Brewster opened his new business, James Brewster Jewelry, in January. The store at 1221 N. Meridian St. in China’s western Xinjiang Portland has a variety of accessories for sale and offers repair work. All repairs are done in-house, Brewster noted. region, as well as over Tai - wan, China’s assertiveness in the South China Sea and the coronavirus pandemic. “We got a defensive Brewster has opened Portland store response,” Secretary of By BAILEY CLINE he’s back to running a Portland ding rings and bridal sets. -

The Unquiet Dead: Race and Violence in the “Post-Racial” United States

The Unquiet Dead: Race and Violence in the “Post-Racial” United States J.E. Jed Murr A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: Dr. Eva Cherniavsky, Chair Dr. Habiba Ibrahim Dr. Chandan Reddy Program Authorized to Offer Degree: English ©Copyright 2014 J.E. Jed Murr University of Washington Abstract The Unquiet Dead: Race and Violence in the “Post-Racial” United States J.E. Jed Murr Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Eva Cherniavksy English This dissertation project investigates some of the ways histories of racial violence work to (de)form dominant and oppositional forms of common sense in the allegedly “post-racial” United States. Centering “culture” as a terrain of contestation over common sense racial meaning, The Unquiet Dead focuses in particular on popular cultural repertoires of narrative, visual, and sonic enunciation to read how histories of racialized and gendered violence circulate, (dis)appear, and congeal in and as “common sense” in a period in which the uneven dispensation of value and violence afforded different bodies is purported to no longer break down along the same old racial lines. Much of the project is grounded in particular in the emergent cultural politics of race of the early to mid-1990s, a period I understand as the beginnings of the US “post-racial moment.” The ongoing, though deeply and contested and contradictory, “post-racial moment” is one in which the socio-cultural valorization of racial categories in their articulations to other modalities of difference and oppression is alleged to have undergone significant transformation such that, among other things, processes of racialization are understood as decisively delinked from racial violence. -

SYMBOLISM in AFRO-AMERICAN SLAVE SONGS THESIS Presented

3 4 I SYMBOLISM IN AFRO-AMERICAN SLAVE SONGS IN THE PRE-CIVIL WAR SOUTH THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE By Jeannie Chaney Sebastian, B. S. Denton, Texas December, 1976 Sebastian, Jeannie C., Symbolism in Afro-American Slave Songs in the Pre-Civil War South. Master of Science (Speech Communication and Drama), December, 1976. This thesis examines the symbolism of thirty-five slave songs that existed in the pre-Civil War South in the United States in order to gain a more profound insight into the values of the slaves. The songs chosen were representative of the 300 songs reviewed. The methodology used in the analysis was adapted from Ralph K. White's Value Analysis: The Nature and Use of the Method. The slave songs provided the slaves with an opportunity to express their feelings on matters they deemed important, often by using Biblical symbols to "mask" the true meanings of their songs from whites. The major values of the slaves as found in their songs were independence, justice, determination, religion, hope, family love, and group unity. 1976 LINDA JEAN CHANEY SEBASTIAN ALL RIGHTS RESERVED TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES . iv Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . 0 . 1 II. THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF SLAVERY AND SLAVE SONGS . .. 26 III. VALUE ANALYSIS OF THE SLAVE SONGS . 64 IV. THE CONCLUSION . 0 . 91 APPENDIX . 0 0 0 . 98 BIBLIOGRAPHY . S. 0 0 0 .114 iii LIST OF TABLES Table Page I. Frequency Charts . -

Signal Songs of the Underground Railroad | 1

SIGNAL SONGS OF THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD | 1 SIGNAL SONGS OF THE UNDEGROUND RAILROAD with Dr. Phyllis Wade Recommended for Ages 7-14 Grades 2 to 8 A Reproducible Learning Guide for Educators This guide is designed to help educators prepare for, enjoy, and discuss Signal Songs of the Underground Railroad It contains background, discussion questions and activities appropriate for ages 7 to 14. Programs Are Made Possible, In Part, By Generous Gifts From: The Nora Roberts Foundation Siewchin Yong Sommer Discovery Theater ● P.O. Box 23293, Washington, DC ● www.discoverytheater.org Like our Facebook Page ● Follow us on Twitter: Smithsonian Kids ● Follow us on Instagram: SmithsonianAssociates SIGNAL SONGS OF THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD | 2 ABOUT THE ARTIST How do you describe a former banker who has performed for a U.S. president, been a member of one of the first Christian rock bands in America, and earned a master’s degree in education while raising two teenagers and serving as the dean of students at the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York? Dr. Wade provides a partial answer by saying that she “crammed a four-year college education into eight years,” a boast that speaks to the unconventional approach taken to her life’s work. Guided by an insatiable curiosity and driven by a passionate love of music, Dr. Wade completed a bachelor’s degree in voice at Roberts Wesleyan College while taking the occasional semester off to tour with her rock group, The Sons of Thunder. This thirst for travel subsequently took her to Kenya where she sang for church groups in and around he city of Nairobi. -

Steal Away May 2020 Arr

For the West Side Singers Steal Away May 2020 arr. E. Hofacker African American Spiritual molto legato, appasionato 60 solo on melody then m1 Steal a-way steal a-way, steal a-way to Je - su - s. Steal a-way, Sop/Alto Steal a way, steal a way, steal a way to Je su s. Steal a way, Steal a-way, steal a-way, steal a - way to Je su s. Steal a-way, Ten/Bass Steal a-way, steal a-way, steal a - way to Je su s. Steal a-way, 2 6 oo - - - - - - steal a-way home. I ain't got long to stay here. SA. steal a-way home. I ain't got long to stay here. oo - - - - - - TB steal a-way home. I ain't got long to stay here. Steal a-way, steal a-way, steal a-way home. I ain't got long to stay here. Steal a-way, steal a-way, 11 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - SA. Steal a-way, steal a-way home. - - - - - - - - - Steal a way, steal a way home. steal a - way to Je su s. oo - - - - - - - - - TB steal a - way to Je su s. oo - - - - - - - - - 3 Like thunder 15 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - I ain't got long to stay here. - - - - - - - My Lord He SA. Like thunder I ain't got long to stay My Lord He Like thunder - - - - - - I ain't got long to stay here. My Lord He TB Like thunder - - - - - - I ain't got long to stay here. My Lord He 19 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - SA. calls me, He calls me by the thunder. The trum-pets sound wi - calls me, He calls me by the thu nder.