The Role for the UPE Project in Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

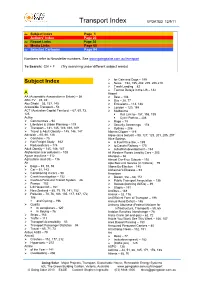

Transport Index UPDATED 12/9/11

Transport Index UPDATED 12/9/11 [ Subject Index Page 1 [ Authors’ Index Page 23 [ Report Links Page 30 [ Media Links Page 60 [ Selected Cartoons Page 94 Numbers refer to Newsletter numbers. See www.goingsolar.com.au/transport To Search: Ctrl + F (Try searching under different subject words) ¾ for Cats and Dogs – 199 Subject Index ¾ News – 192, 195, 202, 205, 206,210 ¾ Trash Landing – 82 ¾ Tarmac Delays in the US – 142 A Airport AA (Automobile Association in Britain) – 56 ¾ Best – 108 ABC-TV – 45, 49 ¾ Bus – 28, 77 Abu Dhabi – 53, 137, 145 ¾ Emissions – 113, 188 Accessible Transport – 53 ¾ London – 120, 188 ACT (Australian Capital Territory) – 67, 69, 73, ¾ Melbourne 125 Rail Link to– 157, 198, 199 Active Cycle Path to – 206 ¾ Communities – 94 ¾ Rage – 79 ¾ Lifestyles & Urban Planning – 119 ¾ Security Screenings – 178 ¾ Transport – 141, 145, 149, 168, 169 ¾ Sydney – 206 ¾ Travel & Adult Obesity – 145, 146, 147 Alberta Clipper – 119 Adelaide – 65, 66, 126 Algae (as a biofuel) – 98, 127, 129, 201, 205, 207 ¾ Carshare – 75 Alice Springs ¾ Rail Freight Study – 162 ¾ A Fuel Price like, – 199 ¾ Reduced cars – 174 ¾ to Darwin Railway – 170 Adult Obesity – 145, 146, 147 ¾ suburban development – 163 Afghanistan (car pollution) – 108 All Western Roads Lead to Cars – 203 Agave tequilana – 112 Allergies – 66 Agriculture (and Oil) – 116 Almost Car-Free Suburb – 192 Air Alps Bus Link Service (in Victoria) – 79 ¾ Bags – 89, 91, 93 Altona By-Election – 145 ¾ Car – 51, 143 Alzheimer’s Disease – 93 ¾ Conditioning in cars – 90 American ¾ Crash Investigation -

City Development World 2007 Hilton Hotel, Sydney 5 June 2007

The Centrality of Public Consciousness to Improvements in Planning, Architecture and Design P J Keating City Development World 2007 Hilton Hotel, Sydney 5 June 2007 When your conference organisers discussed with me the topic of my address today, they accepted my suggestion that it should be around ‘the centrality of public consciousness in the improvement in planning, architecture and design’. I proposed this for the reason that the only true arbiter of the value of architecture, design and the built environment is the community itself. These questions can never be left solely to the professions, architectural panels or municipal planners. Though much of what is to be built will be expressly decided by the professions, panels of the sort and by planners etc, they will be informed by the prevailing ambience of opinion and culture and by the aspirations of the community they serve. No renowned period of architecture or indeed, cities generally regarded as attractive, ever came to pass without the desire of the respective communities to lift themselves up to something better. And architecture, providing that base requirement of shelter, has often been the modality which has given expression to these new epochs. The Renaissance, with all that it brought forth in architecture, did not occur simply because a clutch of architects gathered to themselves a new regard for Roman and ancient Greek architectural forms. Rather, the inquiry and social flowering which occurred after the long middle ages, gave those architects the authority and the encouragement to create a new classical language in celebration of that renaissance. In other words, it was the aspiration of those peoples who were reaching for something better. -

Chapter 11), Making the Events That Occur Within the Time and Space Of

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION: IN PRAISE OF BABBITTRY. SORT OF. SPATIAL PRACTICES IN SUBURBIA Kenneth Jackson’s Crabgrass Frontiers, one of the key histories of American suburbia, marshals a fascinating array of evidence from sociology, geography, real estate literature, union membership profiles, the popular press and census information to represent the American suburbs in terms of population density, home-ownership, and residential status. But even as it notes that “nothing over the years has succeeded in gluing this automobile-oriented civilization into any kind of cohesion – save that of individual routine,” Jackson’s comprehensive history under-analyzes one of its four key suburban traits – the journey-to-work.1 It is difficult to account for the paucity of engagements with suburban transportation and everyday experiences like commuting, even in excellent histories like Jackson’s. In 2005, the average American spent slightly more than twenty-five minutes per day commuting, a time investment that, over the course of a year, translates to more time commuting than he or she will likely spend on vacation.2 Highway-dependent suburban sprawl perpetually moves farther across the map in search of cheap available land, often moving away from both traditional central 1 In the introduction, Jackson describes journey-to-work’s place in suburbia with average travel time and distance in opposition to South America (home of siestas) and Europe, asserting that “an easier connection between work and residence is more valued and achieved in other cultures” (10). 2 One 2003 news report calculates the commuting-to-vacation ratio at 5-to-4: “Americans spend more than 100 hours commuting to work each year, according to American Community Survey (ACS) data released today by the U.S. -

Elizabeth Farrelly

Elizabeth Farrelly Columnist, author and speaker on architecture and public issues Dr Elizabeth Farrelly is a Sydney-based columnist and author and a regular commentator, broadcaster, blogger and critic on architecture and public issues. Elizabeth trained in architecture and philosophy, practiced in London and Bristol and holds a PhD in urbanism from the University of Sydney, where she is also a former Adjunct Associate Professor. As an independent Sydney City Councillor (1991-95), Elizabeth initiated Sydney’s first heritage and laneway protection policies, and was inaugural chair of the Australia Award for Urban Design (1998). She was also Manager Special Projects at the City of Sydney during the Olympic preparations (1998-2000) and is an award-winning writer and published author. Elizabeth Farrelly is a highly respected speaker and her many and varied speaking engagements include the Jack Zunz lecture at the Sydney Opera House, the Walter Burley Griffin lecture at the Science Academy in Canberra, the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects Margaret Hendry Lecture, Canberra, the Sydney, Byron Bay and Adelaide Writers Festivals, the Sydney Festival of Dangerous Ideas, the Adelaide Festival of Ideas, the Art Gallery of NSW ‘Art After Hours’ talks and Ecobuild (London). She has also addressed the Sydney Institute, the Independent Scholars Association, Politics in the Pub, the Australian Institute of Architects, the Planning Institute of Australia, the Sydney Greens, Sydney Design Week, the University of Sydney Sesquicentenary Colloquium Dinner and the Fabian Society, Sydney. Elizabeth Farrelly holds a number of national and international writing awards. As Assistant Editor of The Architectural Review (London) Elizabeth edited the August 1986 special issue ‘The New Spirit’, which won the Paris-based CICA award for architectural criticism. -

Sydney Opera House

Table of Contents Sydney Opera House Slide/s Part Description 1N/ATitle 2 N/A Table of Contents 3~35 1 The Spirit of Tubowgule 36~151 2 The Competition 152~196 3 The Vikings 197~284 4 The Red Book 285~331 5 The Gold Book 332~381 6 The Platform 382~477 7 The Spherical Solution 478~537 8 Phantom of the Opera House 538~621 9 Shell Game 622~705 10 Fenestration 706~786 11 Problems & Solutions 787~813 12 Making Things Right 814~831 13 Liebestraum 832~879 14 Colors of the Night Splendid Geometry 1 880~900 15 Legacy 2 Part 1 First Fleet The Spirit of Tubowgule 3 4 On January 25th 1788, Captain Arthur Phillip (left) of His Majesty’s Ship (HMS) Supply entered a vast, undiscovered and secure harbor extending inland for many miles. The next day - with the indigenous (Aboriginal) Gadigal people watching intently (from a distance), Captain Phillip went ashore and planted the Union Jack on the new found land claiming it for God, King (George III)and country. Over the next few days, the rest of the First Fleet arrived with its cargo of 730 prisoners, most convicted of petty crimes or as dbtdebtors. UdUnder armed guard, theprisoners commenced unloading provisions, clearing land and building shelters. Though prisoners in a strange, distant land of the southern oceans, the prisoners were relieved that their long sea voyage from England was at its end. A pre-fabricated canvas “Government House” was established and the convicts were housed in an area along the harbor’s shore A period oil painting of Captain Phillip’s First Fleet arriving in Sydney which came to be known as “The Rocks.” By Cove (a.k.a. -

Today's News - May 22, 2006 Arcspace Brings Us Two Hot L.A

Home Yesterday's News Calendar Contact Us Subscribe Today's News - May 22, 2006 ArcSpace brings us two hot L.A. projects. -- A Frenchman in Spain takes International High-Rise Prize (commendations not too shabby either). -- NYT Sunday Magazine totally devoted to architecture (plan to spend some time with this one!). -- Farrelly not just a bit suspicious of two new books extolling the virtues of suburbanism. -- Thumbs-up and thumbs-down on New Urbanist communities (visiting local "villages" is a "great deal less expensive that visiting movie studios in Los Angeles" is one way to look at them). -- Does "quirky" architecture make a town tacky or welcoming? -- Big plans for U.K.'s Cowgate (make that the much more hip "SoCo"). -- Some out-of-the-box thinking for a green Olympics could give Chicago the edge. -- Foster wins big with school contracts - but not everyone is convinced it's the right way to go. -- A piece of "fleshy, juicy fruit" of a new store for Apple is drawing the crowds. -- Vision for Orange County Great Park is complex with a simple intention. -- Montréal is first city in North America to be designated part of UNESCO's Creative Cities Network. -- Some "fantastically futuristic hotel designs" await visitors to the World Cup in Germany. -- Demand for Ando everywhere. -- Barbican exhibit of futuristic cities imagined between 1956-2006, but truly radical visions are found in films. -- Fuller/Noguchi show "explores their rapport." -- Three winners in AIA/HUD Housing and Design Awards. -- Once we couldn't resist: a report on Libeskind's 60th birthday bash (be sure to check out NYT Mag to find out why he wears those glasses). -

PROOF COPY – Not for Distribution

PROOF COPY – Not For Distribution 216 PROOF COPY – Not For Distribution Aesthetics of Sustainable Architecture Edited by Sang Lee Published by 010 Publishers, Rotterdam, Netherlnads Table of Contents Words 01 Foreword 355 02 Acknowledgements 141 03 Introduction 9 751 04 The Aesthetics of Architectural Consumption (No images) 9 318 Glen Hill 05 What Does Sustainability Look Like? (No images) 4 552 Matthias Sauerbruch & Louisa Hutton 06 Solar Aesthetic (19 images) 7 103 Ralph L. Knowles 07 The Architecture of the Passively Tempered Environment (11 images) 6 522 Keith N. Bothwell 08 Qualitative and Quantitative Traditions in Sustainable Design (12 images) 8 294 John Brennan 09 Urbanization and Discontents: Megaform and Sustainability (8 images) 5 016 Kenneth Frampton 10 Landscape Aesthetics for Sustainable Architecture (10 images) 5 528 Daniel Jauslin 11 Building Envelope as Surface (No images) 7 167 Sang Lee & Stefanie Holzheu 12 The Sustainable Indigenous Vernacular: Interrogating a Myth (8 images) 8 434 Nezar AlSayyad & Gabriel Arboleda 1 PROOF COPY – Not For Distribution 13 The Qanats in Yazd: The Dilemmas of Sustainability & Conservation (16 images) 7 299 Vinayak Bharne 14 The Vernacular, the Iconic and the Fake (4 images) 4 613 Harald N. Røstivk 15 Natural Architecture (8 images) 2 664 Kengo Kuma 16 The Concept and Aesthetics of Sustainable Building in Japan (14 images) 5 605 Minna Sunikka-Blank 17 Durability in Housing – The Aesthetics of the Ordinary (6 images) 8 229 Marie Antoinette Glaser 18 Environmental Issues as Context (8 images) -

Big Cities Big Ideas Big Australia

BIG CITIES BIG IDEAS BIG AUSTRALIA Danica May Camacho, the world’s seven billionth person. (Getty Images) INTRODUCTION ‘There will be no sustainable world without 1 sustainable cities.’ Herbert Giradet On 31 October 2011, the United Nations awarded newborn Danica May Camacho of the 1 Girardet, H., Creating Sustainable Cities, Green Books, Devon, 2006. Philippines the somewhat dubious honour of being the seven billionth human being. Like 2 Lynas, M., (Jan 2012) The Smart Way the majority of the world’s population in the 21st century, Danica May Camacho will in all to Play God with Earth’s Limited Land, Scientific American, p. 5. <http:// likelihood live out her life in a big city aspiring to better material conditions. She will be part of www.scientificamerican.com/article. the greatest surge of urbanisation ever to occur in human history: every year, 13 cities of over cfm?id=smart-way-to-play-god-with- five million citizens each will need to built to absorb the flow.2 By the time Danica celebrates limited-land>. 3 United Nations, Department of her 40th birthday in 2051, the global population will have reached nine billion, and 10 billion economic and social affairs, World as she celebrates her 80th.3 Shortly thereafter however the global population is expected to population prospects, <http://esa. un.org/unpd/wpp/Other-Information/ stabilise. Why? faq.htm#q1>. The UN’s latest figures Because of cities. (2010 Revision) indicate a total population of 9.3 billion in 2050 and By this century’s end as the majority of the world’s population comes to live in cities – 10 billion in 2083, see press release: gaining greater access to education and experiencing congestion, competition and <http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/ Documentation/pdf/WPP2010_Press_ consumerism – overall population growth is expected to stagnate and thereafter decline. -

A Landscape of Familiarity

A Landscape of Familiarity Tina Barahanos Submitted for the degree of Masters of Fine Arts College of Fine Arts University of New South Wales 2010 ORIGINALITY STATEMENT ‘I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged.’ Signed Date COPYRIGHT STATEMENT ‘I hereby grant the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or dissertation in whole or part in the University libraries in all forms of media, now or here after known, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I retain all proprietary rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. I also authorise University Microfilms to use the 350 word abstract of my thesis in Dissertation Abstract International (this is applicable to doctoral theses only). -

Today's News - November 11, 2005 Urban Land Institute Conference Tackles Less Standard - but Very Timely - Concerns

Home Yesterday's News Contact Us Subscribe Today's News - November 11, 2005 Urban Land Institute conference tackles less standard - but very timely - concerns. -- Mostly thumbs-down for new architecture in the 2005 European Capital of Culture. -- Thumbs-up and thumbs-down for Denver projects and exhibit. -- Malaysian mindset too concerned with how they look on the outside. -- Big plans to resurrect Bethlehem Steel plant, the nation's largest abandoned industrial site. -- Will Manhattan follow London's example with midtown tolls? -- A Delaware factory/office is a "spunky little building...proof that corporate architecture can be intimate and individual." -- An extremely planned community for Nevada. -- Giddy over a Madison, WI, redevelopment project. -- Vancouver International Film Centre is high-tech and high design. -- A small Australian practice with a big presence. To subscribe to the free daily newsletter click here It's in the Water: At the Urban Land Institute's annual meeting...familiar themes of increasing sprawl and shrinking margins melded with less standard discussions...such as emerging demographic trends and natural resource and land management...right now is the moment to squarely face these concerns.- The Slatin Report Little to show for year as European Capital of Culture: Accolades for the Glucksman Gallery have obscured the humdrum quality of much of what's being built in Cork. By Frank McDonald -- Project Architects; Cashman and Associates; Reddy O'Riordan Staehli; Conroy Architecture; Derek Tynan Architects; Scott -

CTBUH Research Paper Title: Debating Tall: Is Australian High

CTBUH Research Paper ctbuh.org/papers Title: Debating Tall: Is Australian High-Rise Housing On the Right Track? Authors: Chris Johnson, CEO, Urban Taskforce Elizabeth Farrelly, Associate Professor, Australian School of Urbanism Subjects: Social Issues Urban Design Keywords: Comfort Connectivity Residential Publication Date: 2017 Original Publication: CTBUH Journal, 2017 Issue IV Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / Chris Johnson; Elizabeth Farrelly Debating Tall Is Australian High-Rise Housing On the Right Track? Australia is at a critical decision point about how to manage projected growth. Historically, the response has been to build suburban sprawl, but this is no longer considered sustainable. Today the question is; how to densify and maintain the high quality of life for which Australian cities are famous? We ask, “Is multifamily high-rouse housing in urban Australia on the right track?” YES right track with high-rise housing in mouthing the words written for them by Chris Johnson, CEO, Urban Taskforce Australian cities – so long as we are locating the development lobby. them near the metro. Sydney’s population has reached five Most egregious of all, developer-led million people, and over the next 40 years is planning has no concern whatsoever for heading to eight million people. The big NO public amenity or space, and little for the change will be in density, in public Elizabeth Farrelly, Associate Professor, private amenity it should in theory transport and in the form of the city. -

About the Course Course Design Aims Approach Outcomes

Built Environment Learning and Teaching Showcase 2016 Re-Enchanting the City: Designing the Human Habitat Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) Central Park Sydney One Central Park heliostat & light show Irving Street Brewery adaptive reuse About the course Course design Approach Re-Enchanting the City: Designing the Human aims The material was structured in 3 layers: Habitat MOOC is an introduction to the 1. Academic – video discussions by academics of the Built interdisciplinary nature of city making, through The course was created with Environment. a cutting-edge, high-density urban infill project intensions to: as case study: Sydney’s Central Park. 2. Profession and stakeholders – interviews with those Develop expertise in fully online involved with Central Park Sydney. The case study is used to explore the course delivery for a large audience. 3. Narrative – Associate Professor (Practice) Elizabeth Farrelly interdependencies of the various built Promote the Faculty and the giving a perspective on Central Park and weekly themes. environment professions, including urban design, programs to potential students. architecture, construction management, planning, Each week had a Built Environment academic lead that sustainable development, landscape architecture, Test and explore a course that could introduced the themes as well as its specific discipline focus. interior architecture and industrial design. form a common experience for first Videos were supplFNFOUed with external resources, year students in the Faculty. Since the course was designed to be including infographics illustrating elements of Central introductory, it is also suitable for high school Park and the built environment disciplines. students, and the learning activity is primarily Social Learning included discussions around focused through rich discussions - promoting a social questions and sharing of participants own images related to engagement amongst participants.