Big Cities Big Ideas Big Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

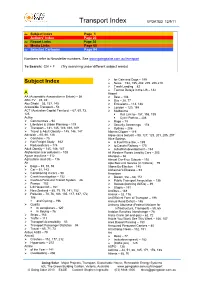

Transport Index UPDATED 12/9/11

Transport Index UPDATED 12/9/11 [ Subject Index Page 1 [ Authors’ Index Page 23 [ Report Links Page 30 [ Media Links Page 60 [ Selected Cartoons Page 94 Numbers refer to Newsletter numbers. See www.goingsolar.com.au/transport To Search: Ctrl + F (Try searching under different subject words) ¾ for Cats and Dogs – 199 Subject Index ¾ News – 192, 195, 202, 205, 206,210 ¾ Trash Landing – 82 ¾ Tarmac Delays in the US – 142 A Airport AA (Automobile Association in Britain) – 56 ¾ Best – 108 ABC-TV – 45, 49 ¾ Bus – 28, 77 Abu Dhabi – 53, 137, 145 ¾ Emissions – 113, 188 Accessible Transport – 53 ¾ London – 120, 188 ACT (Australian Capital Territory) – 67, 69, 73, ¾ Melbourne 125 Rail Link to– 157, 198, 199 Active Cycle Path to – 206 ¾ Communities – 94 ¾ Rage – 79 ¾ Lifestyles & Urban Planning – 119 ¾ Security Screenings – 178 ¾ Transport – 141, 145, 149, 168, 169 ¾ Sydney – 206 ¾ Travel & Adult Obesity – 145, 146, 147 Alberta Clipper – 119 Adelaide – 65, 66, 126 Algae (as a biofuel) – 98, 127, 129, 201, 205, 207 ¾ Carshare – 75 Alice Springs ¾ Rail Freight Study – 162 ¾ A Fuel Price like, – 199 ¾ Reduced cars – 174 ¾ to Darwin Railway – 170 Adult Obesity – 145, 146, 147 ¾ suburban development – 163 Afghanistan (car pollution) – 108 All Western Roads Lead to Cars – 203 Agave tequilana – 112 Allergies – 66 Agriculture (and Oil) – 116 Almost Car-Free Suburb – 192 Air Alps Bus Link Service (in Victoria) – 79 ¾ Bags – 89, 91, 93 Altona By-Election – 145 ¾ Car – 51, 143 Alzheimer’s Disease – 93 ¾ Conditioning in cars – 90 American ¾ Crash Investigation -

The Garden of Australian Dreams: the Moral Rights of Landscape Architects

EDWARD ELGAR THE GARDEN OF AUSTRALIAN DREAMS: THE MORAL RIGHTS OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS DR MATTHEW RIMMER SENIOR LECTURER ACIPA, FACULTY OF LAW, THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY ACIPA, Faculty Of Law, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, 0200 Work Telephone Number: (02) 61254164 E-Mail Address: [email protected] THE GARDEN OF AUSTRALIAN DREAMS: THE MORAL RIGHTS OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS DR MATTHEW RIMMER* * Matthew Rimmer, BA (Hons)/ LLB (Hons) (ANU), PhD (UNSW), is a Senior Lecturer at ACIPA, the Faculty of Law, the Australian National University. The author is grateful for the comments of Associate Professor Richard Weller, Tatum Hands, Dr Kathy Bowrey, Dr Fiona Macmillan and Kimberlee Weatherall. He is also thankful for the research assistance of Katrina Gunn. 1 Prominent projects such as National Museums are expected to be popular spectacles, educational narratives, tourist attractions, academic texts and crystallisations of contemporary design discourse. Something for everyone, they are also self-consciously set down for posterity and must at some level engage with the aesthetic and ideological risks of national edification. Richard Weller, designer of the Garden of Australian Dreams1 Introduction This article considers the moral rights controversy over plans to redesign the landscape architecture of the National Museum of Australia. The Garden of Australian Dreams is a landscaped concrete courtyard.2 The surface offers a map of Australia with interwoven layers of information. It alludes to such concepts as the Mercator Grid, parts of Horton’s Map of the linguistic boundaries of Indigenous Australia, the Dingo Fence, the 'Pope’s Line', explorers’ tracks, a fibreglass pool representing a suburban swimming pool, a map of Gallipoli, graphics common to roads, and signatures or imprinted names of historical identities.3 There are encoded references to the artistic works of iconic Australian painters such as Jeffrey Smart, Sidney Nolan, Arthur Boyd, and Gordon Bennett. -

City Development World 2007 Hilton Hotel, Sydney 5 June 2007

The Centrality of Public Consciousness to Improvements in Planning, Architecture and Design P J Keating City Development World 2007 Hilton Hotel, Sydney 5 June 2007 When your conference organisers discussed with me the topic of my address today, they accepted my suggestion that it should be around ‘the centrality of public consciousness in the improvement in planning, architecture and design’. I proposed this for the reason that the only true arbiter of the value of architecture, design and the built environment is the community itself. These questions can never be left solely to the professions, architectural panels or municipal planners. Though much of what is to be built will be expressly decided by the professions, panels of the sort and by planners etc, they will be informed by the prevailing ambience of opinion and culture and by the aspirations of the community they serve. No renowned period of architecture or indeed, cities generally regarded as attractive, ever came to pass without the desire of the respective communities to lift themselves up to something better. And architecture, providing that base requirement of shelter, has often been the modality which has given expression to these new epochs. The Renaissance, with all that it brought forth in architecture, did not occur simply because a clutch of architects gathered to themselves a new regard for Roman and ancient Greek architectural forms. Rather, the inquiry and social flowering which occurred after the long middle ages, gave those architects the authority and the encouragement to create a new classical language in celebration of that renaissance. In other words, it was the aspiration of those peoples who were reaching for something better. -

Hotspot Cities

PENN: CURRENT RESEARCH ON SUSTAINABLE URBAN DEVELOPMENT Hotspot Cities Identifying Peri-Urban Conflict Zones in the World’s Biodiversity Hotspots RICHARD WELLER Martin and Margy Meyerson Chair of Urbanism Professor and Chair of Landscape Architecture, Penn School of Design CHIEH HUANG Master of Landscape Architecture (MLA) ‘15, Penn School of Design SARA PADGETT KJAERSGAARD Lecturer in Landscape Architecture, University of New South Wales Zuzanna Drozdz Master of Landscape Architecture (MLA) ‘19, Penn School of Design Naxi Dong Master of Landscape Architecture (MLA) ‘19, Penn School of Design FEBRUARY 2018 2 Penn: Current Research on Sustainable Urban Development | Hotspot Cities INTRODUCTION In the small print of the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) targets there are two statements that place biodiversity and urbanization in the same frame of reference. The first, under Goal 11, states that “…positive economic, social and environmental links [should be supported] between urban, peri-urban and rural areas by strengthening national and regional development planning” and the second, under Goal 15, states that by 2020, “…ecosystem and biodiversity values [should be integrated] into national and local planning and development processes” (UN 2015). These lines of text are important because they specifically seek to transcend a history of Manichean dualism between urban development and conservation. If we are to realize the overarching ambition of the New Urban Agenda and the SDGs then such text needs to be not only taken at its word but translated from theory into practice. Here at the University of Pennsylvania in accordance with the SDGs we are also placing urbanization and biodiversity in the same frame of reference. -

Towards a Bright Future - a Vision for Perth As a Region of 3.5 Million People

Committee for Perth Towards a Bright Future - A vision for Perth as a region of 3.5 million people - A vision for Perth as a region a Bright Future Towards Perth @ 3.5 Million Towards a Bright Future A vision for Perth as a region of 3.5 million people September 2012 Perth @ 3.5 Million Towards a bright future This shining sun symbol depicts the level of effort and input from a range of resources all dedicated to ensure Perth has a bright future when it reaches a population of 3.5 million people. More than four years in the making and involving research, consultation and leadership, this is a unique project that reflects the distinctive role of the Committee for Perth. As a bi-partisan think tank and advocacy group for the region, the Committee is focused on improving the liveability of the Perth metropolitan region by ensuring its vibrancy, cultural diversity, economic prosperity and that it is a city of world class amenity. Contents 1.0 Introduction 3 1.1 Providing Leadership on Perth’s Future 4 2.0 Perth @ 3.5 Million: Project Process 8 3.0 Project Outcomes 10 3.1 A ‘Bright Future’ Scenario for Perth 12 3.2 A ‘Business as Usual’ Scenario for Perth 13 3.3 Delivering a Bright Future – Capitalising on our Strengths & Opportunities and Addressing our Weaknesses & Challenges 16 3.4 Strategy for Action: Vision, Innovation and Collaboration 26 3.5 Recommended Actions by Government 30 3.6 Role of the Committee for Perth 32 Attachments Attachment A - Project Contributors 35 Attachment B - Summary of Perth Perceptions Survey and Perth @ 3.5 Million Workshops 40 Attachment C - Workshop Attendees 43 Attachment D - About The Committee For Perth 45 Attachment E - Committee For Perth Membership 48 Attachment F - References 50 Towards a Bright Future 1 acknowledge Committee for Perth leads and supports a range of projects that make a contribution to the way in which Perth develops 2 Committee For Perth 1.0 Introduction Perth is a city and region that sits on the edge of major opportunity. -

Chapter 11), Making the Events That Occur Within the Time and Space Of

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION: IN PRAISE OF BABBITTRY. SORT OF. SPATIAL PRACTICES IN SUBURBIA Kenneth Jackson’s Crabgrass Frontiers, one of the key histories of American suburbia, marshals a fascinating array of evidence from sociology, geography, real estate literature, union membership profiles, the popular press and census information to represent the American suburbs in terms of population density, home-ownership, and residential status. But even as it notes that “nothing over the years has succeeded in gluing this automobile-oriented civilization into any kind of cohesion – save that of individual routine,” Jackson’s comprehensive history under-analyzes one of its four key suburban traits – the journey-to-work.1 It is difficult to account for the paucity of engagements with suburban transportation and everyday experiences like commuting, even in excellent histories like Jackson’s. In 2005, the average American spent slightly more than twenty-five minutes per day commuting, a time investment that, over the course of a year, translates to more time commuting than he or she will likely spend on vacation.2 Highway-dependent suburban sprawl perpetually moves farther across the map in search of cheap available land, often moving away from both traditional central 1 In the introduction, Jackson describes journey-to-work’s place in suburbia with average travel time and distance in opposition to South America (home of siestas) and Europe, asserting that “an easier connection between work and residence is more valued and achieved in other cultures” (10). 2 One 2003 news report calculates the commuting-to-vacation ratio at 5-to-4: “Americans spend more than 100 hours commuting to work each year, according to American Community Survey (ACS) data released today by the U.S. -

Elizabeth Farrelly

Elizabeth Farrelly Columnist, author and speaker on architecture and public issues Dr Elizabeth Farrelly is a Sydney-based columnist and author and a regular commentator, broadcaster, blogger and critic on architecture and public issues. Elizabeth trained in architecture and philosophy, practiced in London and Bristol and holds a PhD in urbanism from the University of Sydney, where she is also a former Adjunct Associate Professor. As an independent Sydney City Councillor (1991-95), Elizabeth initiated Sydney’s first heritage and laneway protection policies, and was inaugural chair of the Australia Award for Urban Design (1998). She was also Manager Special Projects at the City of Sydney during the Olympic preparations (1998-2000) and is an award-winning writer and published author. Elizabeth Farrelly is a highly respected speaker and her many and varied speaking engagements include the Jack Zunz lecture at the Sydney Opera House, the Walter Burley Griffin lecture at the Science Academy in Canberra, the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects Margaret Hendry Lecture, Canberra, the Sydney, Byron Bay and Adelaide Writers Festivals, the Sydney Festival of Dangerous Ideas, the Adelaide Festival of Ideas, the Art Gallery of NSW ‘Art After Hours’ talks and Ecobuild (London). She has also addressed the Sydney Institute, the Independent Scholars Association, Politics in the Pub, the Australian Institute of Architects, the Planning Institute of Australia, the Sydney Greens, Sydney Design Week, the University of Sydney Sesquicentenary Colloquium Dinner and the Fabian Society, Sydney. Elizabeth Farrelly holds a number of national and international writing awards. As Assistant Editor of The Architectural Review (London) Elizabeth edited the August 1986 special issue ‘The New Spirit’, which won the Paris-based CICA award for architectural criticism. -

The Role for the UPE Project in Australia

The role for the UPE project in Australia Dr Kathryn Davidson, Discipline of Urban and Regional Planning, University of South Australia. Abstract: This paper will reflect on the international experience of the Urban Political Ecology (UPE) project and draw insights in particular from the Australian experience. UPE is an emerging body of work responding to the increasing need for just socio-ecological conditions in our cities. UPE to date has been strong in both Europe and the USA, being driven in particular through the work of key scholars including Swyngedouw and Heynen. The UPE project has been given little attention in Australia, despite rare exceptions such as Vortex Cities by McManus and Lifeboat Cities by Gleeson. UPE is a strongly emerging international project which considers justice, nature and urban life. Its progressive thinking about the urban environment represents heightened concern about the consequences of the uneven distribution of wealth in all forms inherent in neoliberal urbanism. UPE is therefore a catalyst for a more thoughtful understanding of socio-ecological urbanisation. The nature of the social and environmental dimensions are given increased emphasis in the progressive politics of urban development, including concepts such as collective consumption and increased interest in environmental equity, protection and reparation. 1 Introduction After three decades, the impact of neoliberal economic globalisation is evident and is carrying us into natural default (Pelling et al., 2012). New sets of systemic and visible pressure have arisen, including climate change, population growth, resource constraint and their implications for the maintenance of economic growth. At the same time, more than 50 per cent of human beings now live in cities or large urban settlements and by 2050, another 25 per cent of humanity will have moved to urban settings (UNFPA, 2007). -

Sydney Opera House

Table of Contents Sydney Opera House Slide/s Part Description 1N/ATitle 2 N/A Table of Contents 3~35 1 The Spirit of Tubowgule 36~151 2 The Competition 152~196 3 The Vikings 197~284 4 The Red Book 285~331 5 The Gold Book 332~381 6 The Platform 382~477 7 The Spherical Solution 478~537 8 Phantom of the Opera House 538~621 9 Shell Game 622~705 10 Fenestration 706~786 11 Problems & Solutions 787~813 12 Making Things Right 814~831 13 Liebestraum 832~879 14 Colors of the Night Splendid Geometry 1 880~900 15 Legacy 2 Part 1 First Fleet The Spirit of Tubowgule 3 4 On January 25th 1788, Captain Arthur Phillip (left) of His Majesty’s Ship (HMS) Supply entered a vast, undiscovered and secure harbor extending inland for many miles. The next day - with the indigenous (Aboriginal) Gadigal people watching intently (from a distance), Captain Phillip went ashore and planted the Union Jack on the new found land claiming it for God, King (George III)and country. Over the next few days, the rest of the First Fleet arrived with its cargo of 730 prisoners, most convicted of petty crimes or as dbtdebtors. UdUnder armed guard, theprisoners commenced unloading provisions, clearing land and building shelters. Though prisoners in a strange, distant land of the southern oceans, the prisoners were relieved that their long sea voyage from England was at its end. A pre-fabricated canvas “Government House” was established and the convicts were housed in an area along the harbor’s shore A period oil painting of Captain Phillip’s First Fleet arriving in Sydney which came to be known as “The Rocks.” By Cove (a.k.a. -

Canberra, Australia 27–30 October 2016

2016 INTERNATIONAL FESTIVAL OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE CANBERRA, AUSTRALIA 27–30 OCTOBER 2016 ******************** **FESTIVAL PROGRAM** ******************** 4 DAYS + 7 CURATORS 7 BIG THEMES 35 SPEAKERS 50 YEARS 1 PROGRAM #NIMBY2016 PRINCIPAL CORPORATE PARTNER MAJOR CORPORATE PARTNERS SUPPORTING CORPORATE PARTNERS EVENT PARTNERS MEDIA INTERNATIONAL AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE OF PARTNER PARTNER LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS aila.org.au/notinmybackyard IMAGE Shaun Gladwell. Image still from Approach to Mundi Mundi: Silverton Road/Mundi Mundi, 2007. c-type print, 120 x 120 cm, Edition of 5, © Shaun Gladwell. Courtesy Anna Schwartz Gallery. 2 ———–NOT IN MY BACKYARD Table of Contents p04 Welcome p08 Calendar p18 Events p50 Conference Speakers p118 Acknowledgements 3 PROGRAM #NIMBY2016 Welcome Prof Richard Weller 2016 International Festival Creative Director At the same time that the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects (AILA) celebrates its 50th anniversary in 2016, the International Commission on Stratigraphy is expected to formally announce the dawn of the Anthropocene Epoch: a new geological period defined by the fact that the earth’s systems are now fundamentally determined by human activity. The philosophical and practical consequences couldn’t be greater: in short, nature is no longer that ever- providing thing ‘out there’, it is, for better or worse, some- thing we are creating. The landscape of the Anthropocene is a cultural landscape and therefore a question of design. The underlying proposition of this conference is that the major dynamics of the Anthropocene—global urbanisation and climate change—are, at root, landscape architectural in nature. They are interrelated issues to which landscape architects can in theory, and increasing- ly in practice, uniquely apply both scientific knowledge and artistic imagination. -

Today's News - May 22, 2006 Arcspace Brings Us Two Hot L.A

Home Yesterday's News Calendar Contact Us Subscribe Today's News - May 22, 2006 ArcSpace brings us two hot L.A. projects. -- A Frenchman in Spain takes International High-Rise Prize (commendations not too shabby either). -- NYT Sunday Magazine totally devoted to architecture (plan to spend some time with this one!). -- Farrelly not just a bit suspicious of two new books extolling the virtues of suburbanism. -- Thumbs-up and thumbs-down on New Urbanist communities (visiting local "villages" is a "great deal less expensive that visiting movie studios in Los Angeles" is one way to look at them). -- Does "quirky" architecture make a town tacky or welcoming? -- Big plans for U.K.'s Cowgate (make that the much more hip "SoCo"). -- Some out-of-the-box thinking for a green Olympics could give Chicago the edge. -- Foster wins big with school contracts - but not everyone is convinced it's the right way to go. -- A piece of "fleshy, juicy fruit" of a new store for Apple is drawing the crowds. -- Vision for Orange County Great Park is complex with a simple intention. -- Montréal is first city in North America to be designated part of UNESCO's Creative Cities Network. -- Some "fantastically futuristic hotel designs" await visitors to the World Cup in Germany. -- Demand for Ando everywhere. -- Barbican exhibit of futuristic cities imagined between 1956-2006, but truly radical visions are found in films. -- Fuller/Noguchi show "explores their rapport." -- Three winners in AIA/HUD Housing and Design Awards. -- Once we couldn't resist: a report on Libeskind's 60th birthday bash (be sure to check out NYT Mag to find out why he wears those glasses). -

Based Procurement at the National Museum of Australia

Reframing the Dynamics: A Case Study of the Interaction between Architectural Computing and Relationship- Based Procurement at the National Museum of Australia. A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. John Paul Swift School of Architecture, Landscape Architecture and Urban Design University of Adelaide, South Australia. Table of Contents LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................... III LIST OF TABLES..........................................................................................................V ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................VII DECLARATION............................................................................................................IX ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................XI DEDICATIONS ...........................................................................................................XIII PREFACE....................................................................................................................XV 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 1 2 CONTEXTUALISING THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AUSTRALIA ................. 11 2.1 POLITICAL CONTEXT....................................................................................... 11 2.2 INSPIRATIONS