Inaugural Issue Editorial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

October 2019

1 A FREE PUBLICATION FOR THE HOBART MUNICIPALITY Proudly owned and published by Corporate Communicati ons (Tas) Pty Ltd OCTOBER 2019 BUILDING SMART FOR A CONNECTED HOBART DRONES that warn of approaching bushfi res, automated language translators to assist international visitors, and driverless public transport networks are part of a vision to make Hobart CITY TECHNOLOGY one of Australia’s most connected cities. The City of Hobart’s ‘Connected Hobart Framework’ and associat- ed action plan will HITS NEW HEIGHTS STORY CONTINUES PAGE 2 CROON RETURNS TO REVAMPED THEATRE ROYAL From left , CROON members John X, Andrew Colrain and Colin Dean with Croonett e dancer Kirsty Anderton. FULL STORY PAGE 6 2 2 Hobart Observer October 2019 Community News Time has fl own Building smart for a average is 359 mm, and Nearly one year since this refl ects an increasing the election – Time has rainfall defi cit since 2017. fl own since I had the I am confi dent that honour of being elected the City of Hobart has as Lord Mayor of Hobart. been working hard to The past year has connected Hobart prepare us for the inevi- been busy and produc- FROM FRONT PAGE table big fi re. tive, and I have enjoyed guide the implementation We have created 50 getting to know many of of smart technologies hectares of new green you as we enact positive and initiatives in the city By Anna Reynolds fi re breaks between changes in our city. across the next decade. Hobart Lord Mayor every property that In recognition of this “We are working to neighbours our bushland fi rst year, I am continuing position Hobart as Aus- THANKS to all members and upgraded more than my theme of connecting tralia’s most economically, of the Hobart community 100 kilometres of fi re with the community and socially and environmen- who joined the millions trails. -

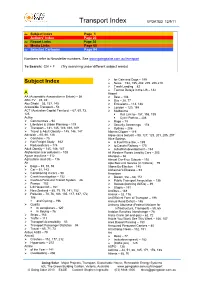

Transport Index UPDATED 12/9/11

Transport Index UPDATED 12/9/11 [ Subject Index Page 1 [ Authors’ Index Page 23 [ Report Links Page 30 [ Media Links Page 60 [ Selected Cartoons Page 94 Numbers refer to Newsletter numbers. See www.goingsolar.com.au/transport To Search: Ctrl + F (Try searching under different subject words) ¾ for Cats and Dogs – 199 Subject Index ¾ News – 192, 195, 202, 205, 206,210 ¾ Trash Landing – 82 ¾ Tarmac Delays in the US – 142 A Airport AA (Automobile Association in Britain) – 56 ¾ Best – 108 ABC-TV – 45, 49 ¾ Bus – 28, 77 Abu Dhabi – 53, 137, 145 ¾ Emissions – 113, 188 Accessible Transport – 53 ¾ London – 120, 188 ACT (Australian Capital Territory) – 67, 69, 73, ¾ Melbourne 125 Rail Link to– 157, 198, 199 Active Cycle Path to – 206 ¾ Communities – 94 ¾ Rage – 79 ¾ Lifestyles & Urban Planning – 119 ¾ Security Screenings – 178 ¾ Transport – 141, 145, 149, 168, 169 ¾ Sydney – 206 ¾ Travel & Adult Obesity – 145, 146, 147 Alberta Clipper – 119 Adelaide – 65, 66, 126 Algae (as a biofuel) – 98, 127, 129, 201, 205, 207 ¾ Carshare – 75 Alice Springs ¾ Rail Freight Study – 162 ¾ A Fuel Price like, – 199 ¾ Reduced cars – 174 ¾ to Darwin Railway – 170 Adult Obesity – 145, 146, 147 ¾ suburban development – 163 Afghanistan (car pollution) – 108 All Western Roads Lead to Cars – 203 Agave tequilana – 112 Allergies – 66 Agriculture (and Oil) – 116 Almost Car-Free Suburb – 192 Air Alps Bus Link Service (in Victoria) – 79 ¾ Bags – 89, 91, 93 Altona By-Election – 145 ¾ Car – 51, 143 Alzheimer’s Disease – 93 ¾ Conditioning in cars – 90 American ¾ Crash Investigation -

The Theme Park As "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," the Gatherer and Teller of Stories

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2018 Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories Carissa Baker University of Central Florida, [email protected] Part of the Rhetoric Commons, and the Tourism and Travel Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Baker, Carissa, "Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5795. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5795 EXPLORING A THREE-DIMENSIONAL NARRATIVE MEDIUM: THE THEME PARK AS “DE SPROOKJESSPROKKELAAR,” THE GATHERER AND TELLER OF STORIES by CARISSA ANN BAKER B.A. Chapman University, 2006 M.A. University of Central Florida, 2008 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, FL Spring Term 2018 Major Professor: Rudy McDaniel © 2018 Carissa Ann Baker ii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the pervasiveness of storytelling in theme parks and establishes the theme park as a distinct narrative medium. It traces the characteristics of theme park storytelling, how it has changed over time, and what makes the medium unique. -

Annual Meeting of Stockholders Letter to Our Stockholders

2020 Proxy Statement Annual Meeting of Stockholders Letter to Our Stockholders Dear Fellow Stockholders: For nearly 25 years, shared values of transparency, responsibility and performance have supported eBay’s mission to empower people and create economic opportunity. As your Board of Directors, we are focused on creating value for you – our stockholders – in increasingly competitive markets, against regulatory headwinds and during unsettled times. Drawing heavily on your input, as well as fresh perspectives from our new directors, we are realizing the vision for the next-generation eBay, a marketplace that can compete and win for the next 25 years. Driving Transformation The last 18 months have been a transformative time for eBay, reflecting the Board’s intense focus on driving the strategic direction of the company. With the assistance and support of executive management, the Board is actively engaged in guiding business strategy and key operational priorities for the company and rigorously exploring and developing opportunities for value creation. The company’s approach to capital allocation, strategic priorities and thought leadership has evolved since the beginning of 2019 as part of this process. Recent value-creating actions approved by the Board include: • Conducted a strategic review of portfolio assets resulting • Enhanced stock buybacks, including $5 billion in 2019 and in the $4 billion sale of StubHub and an ongoing process $4.5 billion planned for 2020 for our Classifieds business • Committed to increased operating efficiency through a • Paid eBay’s first ever quarterly dividend in March 2019 and 3-year plan for at least 2 points of margin accretion, net of increased the rate by 14% in March 2020 reinvestment in critical growth initiatives We also evolved our management team through the recent CEO transition, as well as the reorganization of the senior leadership team to align with our most critical priorities. -

The Immersive Theme Park

THE IMMERSIVE THEME PARK Analyzing the Immersive World of the Magic Kingdom Theme Park JOOST TER BEEK (S4155491) MASTERTHESIS CREATIVE INDUSTRIES Radboud University Nijmegen Supervisor: C.C.J. van Eecke 22 July 2018 Summary The aim of this graduation thesis The Immersive Theme Park: Analyzing the Immersive World of the Magic Kingdom Theme Park is to try and understand how the Magic Kingdom theme park works in an immersive sense, using theories and concepts by Lukas (2013) on the immersive world and Ndalianis (2004) on neo-baroque aesthetics as its theoretical framework. While theme parks are a growing sector in the creative industries landscape (as attendance numbers seem to be growing and growing (TEA, 2016)), research on these parks seems to stay underdeveloped in contrast to the somewhat more accepted forms of art, and almost no attention was given to them during the writer’s Master’s courses, making it seem an interesting choice to delve deeper into this subject. Trying to reveal some of the core reasons of why the Disney theme parks are the most visited theme parks in the world, and especially, what makes them so immersive, a profound analysis of the structure, strategies, and design of the Magic Kingdom theme park using concepts associated with the neo-baroque, the immersive world and the theme park is presented through this thesis, written from the perspective of a creative master student who has visited these theme parks frequently over the past few years, using further literature, research, and critical thinking on the subject by others to underly his arguments. -

2008 CORPORATE RESPONSIBILITY REPORT 2 2008 CORPORATE RESPONSIBILITY REPORT Table of Contents

2008 CORPORATE RESPONSIBILITY REPORT 2 2008 CORPORATE RESPONSIBILITY REPORT Table of Contents Message from Our CEO .........................................5 Product Safety .................................................34 Food Safety ......................................................36 Overview of The Walt Disney Company ...............7 Labor Standards ..............................................36 Media Networks .................................................8 Parks and Resorts .............................................8 Experiences .........................................................36 Studio Entertainment .........................................8 Park Safety .......................................................37 Consumer Products ...........................................8 Accessibility at Disney Parks ...........................37 Interactive Media ..............................................8 Environment ..........................................................39 Governance ...........................................................9 Legacy of Action .................................................40 Public Policy ......................................................9 Environmental Policy ...........................................41 Corporate Responsibility .....................................10 Key Focus Areas ..............................................41 Our Vision.........................................................10 Our Commitments ...............................................42 Corporate -

Tasmanian College of English

Australian National Education Pty Ltd College Of English -Tasmanian- -Sydney NSW- Sydney Hobart 1 TASMANIAN COLLEGE OF ENGLISH Welcoming you to College of English Tasmanian&Sydney NSW Contents 01 About Tasmania 02 About Tasmanian College 04Why choose Tasmania 05 Services and Support 06Working Holiday Course 07How to apply coe.tas.edu.au | English College 0 TASMANIAN COLLEGE OF ENGLISH Tasmania – The State Tasmania is an island approximately the same size as Ireland. Similar Latitude to Madrid, Spain Easy access from Melbourne by air or sea (overnight ferry). Australia’s wilderness state, 2/3 of Tasmania consists of protected national parks, world heritage areas or state forests. Spectacular unspoilt areas provide unlimited scope to experience nature, from the sea to alpine mountain areas, Eco-tourism paradise – World Heritage Park walks and camping treks, white water rafting, rock climbing, abseiling, sea kayaking among dolphins, diving in Tasmania’s famed kelp forests and underwater caves. Tasmania has an extensive network of youth hostels and backpacker hostel providing economical and friendly Hobart – The City accommodation around Tasmania. Walking and biking paradise. Hobart, capital of Australia’s island state of Tasmania. Popular approximately 200,000 and Australia’s second oldest city. Located at the base of Mount Wellington where the Derwent River meets the sea. Hobart surrounds a large harbour which overflows with yachts from all over the world each January at the conclusion of the Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race. Warm summers (average 23°C) and winters (13°C). Hobart’s charm remains untouched by tourism. A perfect destination for students who do not want to be with a crowd of tourists, would like to enjoy an authentic Australian city with access to unspoilt and unpopulated beaches and countryside. -

City Development World 2007 Hilton Hotel, Sydney 5 June 2007

The Centrality of Public Consciousness to Improvements in Planning, Architecture and Design P J Keating City Development World 2007 Hilton Hotel, Sydney 5 June 2007 When your conference organisers discussed with me the topic of my address today, they accepted my suggestion that it should be around ‘the centrality of public consciousness in the improvement in planning, architecture and design’. I proposed this for the reason that the only true arbiter of the value of architecture, design and the built environment is the community itself. These questions can never be left solely to the professions, architectural panels or municipal planners. Though much of what is to be built will be expressly decided by the professions, panels of the sort and by planners etc, they will be informed by the prevailing ambience of opinion and culture and by the aspirations of the community they serve. No renowned period of architecture or indeed, cities generally regarded as attractive, ever came to pass without the desire of the respective communities to lift themselves up to something better. And architecture, providing that base requirement of shelter, has often been the modality which has given expression to these new epochs. The Renaissance, with all that it brought forth in architecture, did not occur simply because a clutch of architects gathered to themselves a new regard for Roman and ancient Greek architectural forms. Rather, the inquiry and social flowering which occurred after the long middle ages, gave those architects the authority and the encouragement to create a new classical language in celebration of that renaissance. In other words, it was the aspiration of those peoples who were reaching for something better. -

CASE 2 1 the Not-So-Wonderful World of Eurodisney

CASE 21 The Not-So-Wonderful World of EuroDisney * —Things Are Better Now at Disneyland Resort Paris BONJOUR, MICKEY! Spills and Thrills Disney had projected that the new theme park would attract 11 million visitors and generate over In April 1992, EuroDisney SCA opened its doors to European visi- $100 million in operating earnings during the fi rst year of opera- tors. Located by the river Marne some 20 miles east of Paris, it was tion. By summer 1994, EuroDisney had lost more than $900 mil- designed to be the biggest and most lavish theme park that Walt lion since opening. Attendance reached only 9.2 million in 1992, Disney Company (Disney) had built to date—bigger than Disney- and visitors spent 12 percent less on purchases than the estimated land in Anaheim, California; Disneyworld in Orlando, Florida; $33 per head. and Tokyo Disneyland in Japan. If tourists were not fl ocking to taste the thrills of the new Euro- Much to Disney management’s surprise, Europeans failed to Disney, where were they going for their summer vacations in 1992? “go goofy” over Mickey, unlike their Japanese counterparts. Be- Ironically enough, an unforeseen combination of transatlantic air- tween 1990 and early 1992, some 14 million people had visited fare wars and currency movements resulted in a trip to Disneyworld Tokyo Disneyland, with three-quarters being repeat visitors. A fam- in Orlando being cheaper than a trip to Paris, with guaranteed good ily of four staying overnight at a nearby hotel would easily spend weather and beautiful Florida beaches within easy reach. -

Creating an Inclusive Community

Spring 2018 l No. 39 No. Sergio Rebia leads a drawing demonstration on Application Day at Cal State Fullerton. 51 students from 45 high schools attended, and 75% of them later applied to Ryman Arts Creating an Inclusive Community “I encourage my students to apply [to Ryman Arts] because it forces them out of their bubble of comfort and complacency. Students are exposed to quality art supplies and instruction they may not be able to afford on their own,” says L’lia Thomas (Ms. T) from La Tijera K-8 Academy of Excellence Charter School. Every year, Ryman Arts connects with over 2,000 Ms. T is an exemplary model of the community students through school presentations, community champions we count on to learn about student fairs, and Application Days. These efforts combat needs in our communities. Because of her the challenges that some students experience in initiative, we have continued to build our learning about and completing the application to relationship with La Tijera Charter School and Ms. T (second from left) and students from La Tijera our highly competitive program. Through strong recently added a special in-school workshop for Charter School relationships with public school teachers like her students. Ms. T, we have made great strides in “It was incredible having Miss Robin come out increasing access to Ryman Arts. to my classroom to facilitate a two-day workshop Application Days have been successful for students who are applying. Her approach in in creating a supportive environment my classroom gave students a real taste of what it where prospective students can take an would be like [at Ryman Arts].” introductory drawing class led by one of Ensuring broad access to Ryman Arts remains our faculty and work on a still life that an important part of our efforts because of the can be included in their application. -

Sacred Smoking

FLORIDA’SBANNER INDIAN BANNER HERITAGE BANNER TRAIL •• BANNERPALEO-INDIAN BANNER ROCK BANNER ART? • • THE BANNER IMPORTANCE BANNER OF SALT american archaeologySUMMER 2014 a quarterly publication of The Archaeological Conservancy Vol. 18 No. 2 SACRED SMOKING $3.95 $3.95 SUMMER 2014 americana quarterly publication of The Archaeological archaeology Conservancy Vol. 18 No. 2 COVER FEATURE 12 HOLY SMOKE ON BY DAVID MALAKOFF M A H Archaeologists are examining the pivitol role tobacco has played in Native American culture. HLEE AS 19 THE SIGNIFICANCE OF SALT BY TAMARA STEWART , PHOTO BY BY , PHOTO M By considering ethnographic evidence, researchers EU S have arrived at a new interpretation of archaeological data from the Verde Salt Mine, which speaks of the importance of salt to Native Americans. 25 ON THE TRAIL OF FLORIDA’S INDIAN HERITAGE TION, SOUTH FLORIDA MU TION, SOUTH FLORIDA C BY SUSAN LADIKA A trip through the Tampa Bay area reveals some of Florida’s rich history. ALLANT COLLE ALLANT T 25 33 ROCK ART REVELATIONS? BY ALEXANDRA WITZE Can rock art tell us as much about the first Americans as stone tools? 38 THE HERO TWINS IN THE MIMBRES REGION BY MARC THOMPSON, PATRICIA A. GILMAN, AND KRISTINA C. WYCKOFF Researchers believe the Mimbres people of the Southwest painted images from a Mesoamerican creation story on their pottery. 44 new acquisition A PRESERVATION COLLABORATION The Conservancy joins forces with several other preservation groups to save an ancient earthwork complex. 46 new acquisition SAVING UTAH’S PAST The Conservancy obtains two preserves in southern Utah. 48 point acquisition A TIME OF CONFLICT The Parkin phase of the Mississippian period was marked by warfare. -

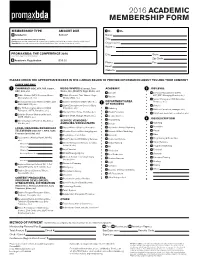

2016 Academic Membership Form

2016 ACADEMIC MEMBERSHIP FORM MEMBERSHIP TYPE AMOUNT DUE Mr. Ms. Academic $49.00* Name: *Must be a full time faculty staff or student. Title: Faculty: must provide current staff ID or other form of teaching verification at a college, university or high school. Student: Must proovide current student ID card and full time class schedule (minumum of 9 units). Organization: Address: PROMAXBDA: THE CONFERENCE 2016 City: State: June 14-16, New York Hilton Midtown Zip Code: Academic Registration $99.00 Phone: Fax: Email: Website: PLEASE CHECK THE APPROPRIATE BOXES IN THE 4 AREAS BELOW TO PROVIDE INFORMATION ABOUT YOU AND YOUR COMPANY CHECK ONE ONLY 1 CHANNELS (NBC, MTV, FOX, Canal+, MSOS/MVPDS (Comcast, Time ACADEMIC 3 JOB LEVEL BBC, A+E, etc) Warner, Star, DIRECTV, Virgin Media, etc.) Educator Executive Management (CMO, Cable Channel (MTV, Discovery, Bravo, Cable (Comcast, Time Warner, Virgin EVP, SVP, Managing Director, etc.) Student Disney Channel, etc.) Media, ONO, etc.) Senior Management (VP, Executive Broadcast/Terrestrial Network (NBC, ZDF, Satellite (DIRECTV, DISH, SKY, etc.) 2 DEPARTMENT/AREA Producer, etc.) CBS, BBC, DR, etc.) OF BUSINESS Game/Entertainment Console (Xbox, Director Pay TV/Subscription Channel (HBO, Playstation, etc) Marketing Mid-Level (producer, manager, etc.) Eurosport, LAPTV, Showtime, etc.) Internet (Hulu, iTunes, Youtube, etc.) On-Air Promotion Entry Level (assistant, coordinator, etc.) Satellite Channel (Audience Network, Mobile (AT&T, Orange, Verizon, etc.) Creative Services ARTE, DW-TV, etc.) Programming 4 JOB