A Landscape of Familiarity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transport Index UPDATED 12/9/11

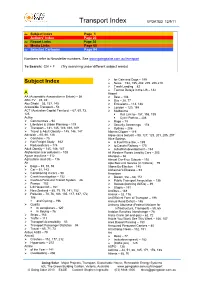

Transport Index UPDATED 12/9/11 [ Subject Index Page 1 [ Authors’ Index Page 23 [ Report Links Page 30 [ Media Links Page 60 [ Selected Cartoons Page 94 Numbers refer to Newsletter numbers. See www.goingsolar.com.au/transport To Search: Ctrl + F (Try searching under different subject words) ¾ for Cats and Dogs – 199 Subject Index ¾ News – 192, 195, 202, 205, 206,210 ¾ Trash Landing – 82 ¾ Tarmac Delays in the US – 142 A Airport AA (Automobile Association in Britain) – 56 ¾ Best – 108 ABC-TV – 45, 49 ¾ Bus – 28, 77 Abu Dhabi – 53, 137, 145 ¾ Emissions – 113, 188 Accessible Transport – 53 ¾ London – 120, 188 ACT (Australian Capital Territory) – 67, 69, 73, ¾ Melbourne 125 Rail Link to– 157, 198, 199 Active Cycle Path to – 206 ¾ Communities – 94 ¾ Rage – 79 ¾ Lifestyles & Urban Planning – 119 ¾ Security Screenings – 178 ¾ Transport – 141, 145, 149, 168, 169 ¾ Sydney – 206 ¾ Travel & Adult Obesity – 145, 146, 147 Alberta Clipper – 119 Adelaide – 65, 66, 126 Algae (as a biofuel) – 98, 127, 129, 201, 205, 207 ¾ Carshare – 75 Alice Springs ¾ Rail Freight Study – 162 ¾ A Fuel Price like, – 199 ¾ Reduced cars – 174 ¾ to Darwin Railway – 170 Adult Obesity – 145, 146, 147 ¾ suburban development – 163 Afghanistan (car pollution) – 108 All Western Roads Lead to Cars – 203 Agave tequilana – 112 Allergies – 66 Agriculture (and Oil) – 116 Almost Car-Free Suburb – 192 Air Alps Bus Link Service (in Victoria) – 79 ¾ Bags – 89, 91, 93 Altona By-Election – 145 ¾ Car – 51, 143 Alzheimer’s Disease – 93 ¾ Conditioning in cars – 90 American ¾ Crash Investigation -

Appendices 2011–12

Art GAllery of New South wAleS appendices 2011–12 Sponsorship 73 Philanthropy and bequests received 73 Art prizes, grants and scholarships 75 Gallery publications for sale 75 Visitor numbers 76 Exhibitions listing 77 Aged and disability access programs and services 78 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander programs and services 79 Multicultural policies and services plan 80 Electronic service delivery 81 Overseas travel 82 Collection – purchases 83 Collection – gifts 85 Collection – loans 88 Staff, volunteers and interns 94 Staff publications, presentations and related activities 96 Customer service delivery 101 Compliance reporting 101 Image details and credits 102 masterpieces from the Musée Grants received SPONSORSHIP National Picasso, Paris During 2011–12 the following funding was received: UBS Contemporary galleries program partner entity Project $ amount VisAsia Council of the Art Sponsors Gallery of New South Wales Nelson Meers foundation Barry Pearce curator emeritus project 75,000 as at 30 June 2012 Asian exhibition program partner CAf America Conservation work The flood in 44,292 the Darling 1890 by wC Piguenit ANZ Principal sponsor: Archibald, Japan foundation Contemporary Asia 2,273 wynne and Sulman Prizes 2012 President’s Council TOTAL 121,565 Avant Card Support sponsor: general Members of the President’s Council as at 30 June 2012 Bank of America Merill Lynch Conservation support for The flood Steven lowy AM, Westfield PHILANTHROPY AC; Kenneth r reed; Charles in the Darling 1890 by wC Piguenit Holdings, President & Denyse -

City Development World 2007 Hilton Hotel, Sydney 5 June 2007

The Centrality of Public Consciousness to Improvements in Planning, Architecture and Design P J Keating City Development World 2007 Hilton Hotel, Sydney 5 June 2007 When your conference organisers discussed with me the topic of my address today, they accepted my suggestion that it should be around ‘the centrality of public consciousness in the improvement in planning, architecture and design’. I proposed this for the reason that the only true arbiter of the value of architecture, design and the built environment is the community itself. These questions can never be left solely to the professions, architectural panels or municipal planners. Though much of what is to be built will be expressly decided by the professions, panels of the sort and by planners etc, they will be informed by the prevailing ambience of opinion and culture and by the aspirations of the community they serve. No renowned period of architecture or indeed, cities generally regarded as attractive, ever came to pass without the desire of the respective communities to lift themselves up to something better. And architecture, providing that base requirement of shelter, has often been the modality which has given expression to these new epochs. The Renaissance, with all that it brought forth in architecture, did not occur simply because a clutch of architects gathered to themselves a new regard for Roman and ancient Greek architectural forms. Rather, the inquiry and social flowering which occurred after the long middle ages, gave those architects the authority and the encouragement to create a new classical language in celebration of that renaissance. In other words, it was the aspiration of those peoples who were reaching for something better. -

Making 18 01–20 05

artonview art o n v i ew ISSUE No.49 I ssue A U n T U o.49 autumn 2007 M N 2007 N AT ION A L G A LLERY OF LLERY A US T R A LI A The 6th Australian print The story of Australian symposium printmaking 18 01–20 05 National Gallery of Australia, Canberra John Lewin Spotted grossbeak 1803–05 from Birds of New South Wales 1813 (detail) hand-coloured etching National Gallery of Australia, Canberra nga.gov.au InternatIonal GallerIes • australIan prIntmakInG • modern poster 29 June – 16 September 2007 23 December 2006 – 6 May 2007 National Gallery of Australia, Canberra National Gallery of Australia, Canberra George Lambert The white glove 1921 (detail) Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney purchased 1922 photograph: Jenni Carter for AGNSW Grace Crowley Painting 1951 oil on composition board National Gallery of Australia, Canberra Purchased 1969 nga.gov.au nga.gov.au artonview contents 2 Director’s foreword Publisher National Gallery of Australia nga.gov.au 5 Development office Editor Jeanie Watson 6 Masterpieces for the Nation appeal 2007 Designer MA@D Communication 8 International Galleries Photography 14 The story of Australian printmaking 1801–2005 Eleni Kypridis Barry Le Lievre Brenton McGeachie 24 Conservation: print soup Steve Nebauer John Tassie 28 Birth of the modern poster Designed and produced in Australia by the National Gallery of Australia 34 George Lambert retrospective: heroes and icons Printed in Australia by Pirion Printers, Canberra 37 Travelling exhibitions artonview ISSN 1323-4552 38 New acquisitions Published quarterly: Issue no. 49, Autumn 2007 © National Gallery of Australia 50 Children’s gallery: Tools and techniques of printmaking Print Post Approved 53 Sculpture Garden Sunday pp255003/00078 All rights reserved. -

A Thousand Encores: the Ballets Russes in Australia

PUBLICITY MATERIAL A Thousand Encores: The Ballets Russes in Australia CONTACT PRODUCTION COMPANY flaming star films 7/32 George Street East Melbourne 3002 Tel: +61 3 9419 8097 Mob: +61 (0)417 107 516 Email: [email protected] EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Sharyn Prentice WRITER / DIRECTOR Mandy Chang PRODUCERS Marianne Latham / Lavinia Riachi EDITOR Karin Steininger Ballets Russes dancer Anna Volkova as the Golden Cockerel in Fokine's Le Coq d'Or A Thousand Encores: The Ballets Russes in Australia SHORT SYNOPSIS A Thousand Encores is the story of how the greatest ballet company of the 20th Century - the celebrated Ballets Russes, came to Australia and awoke a nation, transforming the cultural landscape of conservative 30’s Australia, leaving a rich legacy that lasts to this day. EXTENDED SYNOPSIS A Thousand Encores tells the surprising and little known story of how, over 70 years ago, an extraordinary company of dancers made a deep impact on our cultural heritage. In 1936, the celebrated Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo stepped off a boat into the bright Australian sunlight. With exotic sets and costumes designed by cutting edge-artists and avant-garde music by great composers like Stravinsky, the Ballets Russes inspired a nation and transformed our cultural landscape. Over five years from 1936 to 1940 they came to Australia three times, winning the hearts and minds of Australian audiences, inspiring a generation of our greatest artists - Grace Cossington Smith, Jeffrey Smart and Sidney Nolan - and ultimately sowing the seeds for Australian ballet today. The story is bought alive using a rich archival resource. Australia has the biggest collection of Ballets Russes footage in the world and an impressive photographic record - the most famous pictures taken by a young Max Dupain. -

Chapter 11), Making the Events That Occur Within the Time and Space Of

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION: IN PRAISE OF BABBITTRY. SORT OF. SPATIAL PRACTICES IN SUBURBIA Kenneth Jackson’s Crabgrass Frontiers, one of the key histories of American suburbia, marshals a fascinating array of evidence from sociology, geography, real estate literature, union membership profiles, the popular press and census information to represent the American suburbs in terms of population density, home-ownership, and residential status. But even as it notes that “nothing over the years has succeeded in gluing this automobile-oriented civilization into any kind of cohesion – save that of individual routine,” Jackson’s comprehensive history under-analyzes one of its four key suburban traits – the journey-to-work.1 It is difficult to account for the paucity of engagements with suburban transportation and everyday experiences like commuting, even in excellent histories like Jackson’s. In 2005, the average American spent slightly more than twenty-five minutes per day commuting, a time investment that, over the course of a year, translates to more time commuting than he or she will likely spend on vacation.2 Highway-dependent suburban sprawl perpetually moves farther across the map in search of cheap available land, often moving away from both traditional central 1 In the introduction, Jackson describes journey-to-work’s place in suburbia with average travel time and distance in opposition to South America (home of siestas) and Europe, asserting that “an easier connection between work and residence is more valued and achieved in other cultures” (10). 2 One 2003 news report calculates the commuting-to-vacation ratio at 5-to-4: “Americans spend more than 100 hours commuting to work each year, according to American Community Survey (ACS) data released today by the U.S. -

Mr Jeffrey Smart

Mr Jeffrey Smart The degree of Doctor of the University was conferred upon Australian artist Jeffrey Smart by Chancellor Dame Leonie Kramer at a ceremony held on 2 September 1999. Jeffrey Smart receiving his honorary degree from Chancellor Dame Leonie Kramer, photo G77_4, University of Sydney Archives. Jeffrey Smart and David Malouf at the ceremony, photo, Karen Mork, 'The University of Sydney News', 9 September 1999, University of Sydney Archives. Citation Chancellor I have the honour to present to you Jeffrey Smart for admission to the degree of Doctor of the University. Jeffrey Smart is one of the leading artists of his time. In 1976, the University acquired nineteen of his paintings through a bequest from the estate of A R Renshaw. Jeffrey Smart was born in Adelaide in 1921, and studied at the South Australian School of Arts and Crafts, in Paris with Fernand Leger at the Academie Monmartre, and at La Grande Chaumiere. During his early career, he was art critic for the Daily Telegraph, broadcaster for "Current Art Review" on the ABC, and Phidias, on the children's programme, "The Argonauts". He also taught drawing at the National Art School. Fellow artist, Judy Cassab, recalls Jeffrey Smart in the 1950s as an artist who knew exactly what he wanted. On a trip to La Perouse, he admired the gasworks, while she admired the sea. When asked by him to criticise his work, she said, '''Your contours are so sharp. Can't you make them a bit blurred?' And he replied, 'I don't want them blurred.' He knew where he was going." He was creating the interplay between clearly delineated shapes, structures, space and the human figure. -

Annual Report 2001–2002 Annual Report 2001–2002 NATIONAL GALLERY of AUSTRALIA Annual Report 2001–2002 © National Gallery of Australia

NATIONAL GALLERY OF AUSTRALIA GALLERY NATIONAL NATIONAL GALLERY OF AUSTRALIA Annual Report 2001–2002 Annual Report 2001–2002 Annual Report NATIONAL GALLERY OF AUSTRALIA Annual Report 2001–2002 © National Gallery of Australia ISSN 1323-5192 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Produced by the Publications Department of the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. Printed by Paragon Printers, Canberra, ACT National Gallery of Australia GPO Box 1150, Canberra ACT 2601 www.nga.gov.au cover and left: Paminggir people Lampung, Sumatra, Indonesia Ceremonial textile [tampan] 19th century Cotton, gold thread, dyes; supplement weft Acquired through gift and purchase from the Collection of Robert J. Holmgren and Anita E. Spertus, New York, 2000 iii Contents Letter of Transmittal iii Chairman’s Foreword 1 Director’s Report 3 Performance Report 2001–2002 Outcome and Outputs 7 Corporate Overview 9 Report against Strategic Plan 2001–2004 15 National Gallery of Australia Financial Reports 2001–2002 Independent audit report 54 Statement by Directors 56 Statement of Financial Performance 57 Notes to the Financial Statement 62 Appendixes 1. Council of the National Gallery of Australia 86 2. Management structure at 30 June 2002 88 3. Staff of the National Gallery of Australia at 30 June 2002 89 4. Acquisitions 2001–2002 92 5. Acquisitions including purchases and gifts 1945–2002 116 6. Exhibitions held at the National Gallery of Australia 117 7. Attendance at the National Gallery of Australia 1982–2002 119 8. -

Elizabeth Farrelly

Elizabeth Farrelly Columnist, author and speaker on architecture and public issues Dr Elizabeth Farrelly is a Sydney-based columnist and author and a regular commentator, broadcaster, blogger and critic on architecture and public issues. Elizabeth trained in architecture and philosophy, practiced in London and Bristol and holds a PhD in urbanism from the University of Sydney, where she is also a former Adjunct Associate Professor. As an independent Sydney City Councillor (1991-95), Elizabeth initiated Sydney’s first heritage and laneway protection policies, and was inaugural chair of the Australia Award for Urban Design (1998). She was also Manager Special Projects at the City of Sydney during the Olympic preparations (1998-2000) and is an award-winning writer and published author. Elizabeth Farrelly is a highly respected speaker and her many and varied speaking engagements include the Jack Zunz lecture at the Sydney Opera House, the Walter Burley Griffin lecture at the Science Academy in Canberra, the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects Margaret Hendry Lecture, Canberra, the Sydney, Byron Bay and Adelaide Writers Festivals, the Sydney Festival of Dangerous Ideas, the Adelaide Festival of Ideas, the Art Gallery of NSW ‘Art After Hours’ talks and Ecobuild (London). She has also addressed the Sydney Institute, the Independent Scholars Association, Politics in the Pub, the Australian Institute of Architects, the Planning Institute of Australia, the Sydney Greens, Sydney Design Week, the University of Sydney Sesquicentenary Colloquium Dinner and the Fabian Society, Sydney. Elizabeth Farrelly holds a number of national and international writing awards. As Assistant Editor of The Architectural Review (London) Elizabeth edited the August 1986 special issue ‘The New Spirit’, which won the Paris-based CICA award for architectural criticism. -

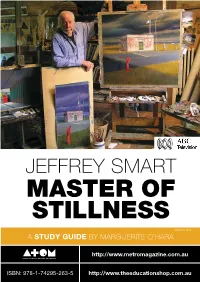

Jeffrey Smart Master of Stillness

JEFFREY SMART MASTER OF STILLNESS © ATOM 2012 A STUDY GUIDE BY MArguerite o’hARA http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-263-5 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au I find it funny that perhaps in 100 years time, if people look at paintings done by the artists of this century, of our century, that the most ubiquitous things, like motor cars and television sets and telephones, don’t appear in any of the pictures. We should paint the things around us. Motor cars are very beautiful. I’m a great admirer of Giorgio Morandi; we all love Morandi, and he had all his props, his different bottles and his things. See, my props are petrol stations and trucks If a good painting comes off, it has a stillness, it has and it’s just the same a perfection, and that’s as great as anything that a thing. It’s a different musician or a poet can do. – Jeffrey Smart range of things. Introduction Jeffrey Smart Jeffrey Smart: Master of Stillness (Catherine Hunter, 2012) sheds light on the early influences of one of our greatest painters. Born in Adelaide in 1921, Smart’s early years were spent discovering the back lanes of the city’s inner suburbs. Now retired from painting, his last work Labyrinth (2011) evokes those memories. It is also a kind of arrival at the painting he was always chasing, never satisfied, hoping the next one on the easel would be the elusive masterpiece, the one that said it all. In this sense, Labyrinth brings a full stop to his career, and at the same time makes for a full, perpetual circle within his life. -

Peter Kingston

PETER KINGSTON Born 1943 Sydney, Australia 2017 State Liberal Government banishes historic Lady class ferries from Sydney Harbour, Sydneysider Walter Reeks (1861 – 1925) originated the design of Sydney double ended ferries, the Lady class ferries, it was Sydney gift to the world, influencing the design of the famous Hong Kong Star ferries 2015 Expedition to Honk Kong with Ann Tompson to see the heritage star ferries and electric trams and work with the Nock Foundation 2012 Launch of Sharknett Seahorses of Balmoral by Charles Waterstreet at the State Library NSW Travel to Italy with Zane Buschman to Rome then onto Arezzo and Sansopulcro to see work of Piero Della Francesca Visit to Jeffrey Smart at the Villa Posticcia Nuova, Arezzo, Italy 2014 Art expedition to Broken Hill with Kevin Conner, Dan Kyle, Ann Tompson, Luke Sciberras, Guy Warren, Euan McLeod, Huy Warren, culminating in an exhibition at the Broken Hill Gallery 2013 Death of Jeffrey Smart Death of Martin Sharp 2010 Expedition to St Petersburg with Jan Cork visiting the Hermitage, Pushkin Museum, the Idiot restaurant and the Nabokov House and Mariinsky Theatre. Then travelling onto Riga, Latvia visiting the Rumble forest holocaust monuments, going onto Tallim to see the Kumu Art Museum with Jon and Tanya Crothers. Stranded in Riga when the volcano in Iceland erupted. Back in Sydney joined artists expedition to stay at Mount Murchison station on the darling river with Chic Gorden, Elisabeth Cummings, Judy Lane, Ian Marr, Luke Sciberras and Ann & Sophie Cape Birthday celebrations -

MUSE Issue 7, March 2014

issue no. 07 MAR 2014 S AU M ST U R ART . CULTURE . ANTIQUITIES . NATURAL HISTORY E A S L U I A M WINNER Best magazine and newsletter A W (Level B) 3 A 01 RDS 2 In recent years, Hollywood has released several big‑budget SYDNEY films set in antiquity, such as Gladiator (2000), Clash of the CONTENTS UNIVERSITY Titans (2010), The Eagle (2011) and, coming in 3D to a cinema MUSEUMS SWORDS, near you in 2014, Pompeii. O1 SWORDS, SANDALS AND THE 19 MUSEUM ENHANCES LIFE Comprising the Macleay However, ever since it emerged as a new technology more Museum, Nicholson Museum SILVER SCREEN AS A STUDENT than a century ago, cinema has been fascinated with the and University Art Gallery SANDALS ancient world. Within a few months of the first public 03 THE VILLAGE AND ELSEWHERE 20 INTO THE FUTURE Open Monday to Friday, 10am to showings of moving images in 1896, the Roman Emperor Nero 4.30pm and the first Saturday of 06 DRAWN FROM EXPERIENCE 22 HEART OF THE COMMUNITY every month 12 to 4pm was brought to life on the screen trying out poisons on his Closed on public holidays. slaves. By the time sound was introduced into movies in the 08 ‘LIKE’ A COCKATOO 24 AROUND THE WORLD General admission is free. AND THE late 1920s, more than 800 films had been made that drew 27 THERE IS A BURIED DRAGON Become a fan on Facebook and inspiration from ancient Greece, Rome, Egypt or the Bible. 10 A GENTLEMAN AND A SCHOLAR follow us on Twitter.