Enantiomer-Specific Detection of Chiral Molecules Via Microwave Spectroscopy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enantioselective Synthesis of the (1S,5R)-Enantiomer of Litseaverticillols a and B

Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem., 70 (10), 2564–2566, 2006 Note Enantioselective Synthesis of the (1S,5R)-Enantiomer of Litseaverticillols A and B y Akira MORITA, Hiromasa KIYOTA, and Shigefumi KUWAHARA Laboratory of Applied Bioorganic Chemistry, Graduate School of Agricultural Science, Tohoku University, Tsutsumidori-Amamiyamachi, Aoba-ku, Sendai 981-8555, Japan Received May 8, 2006; Accepted May 31, 2006; Online Publication, October 7, 2006 [doi:10.1271/bbb.60253] An enantioselective synthesis of the (1S,5R)-enan- which have recently culminated in the first enantiose- tiomer of litseaverticillols A and B was accomplished in lective total synthesis of (1R,5S)-(À)-1 and (1R,5S)-(À)- line with our previously reported synthetic pathway for 2.4) In this note, we describe the synthesis of their their (1R,5S)-enantiomer. The use of ‘‘EtSCeCl2’’ pre- enantiomers directed toward an evaluation of the differ- pared from EtSLi and CeCl3, instead of previously ence in biological activity between the enantiomers of employed EtSLi itself, for the formation of thiol ester litseaverticillols A and B. intermediates prevented any undesirable epimerization Our synthesis of (1S,5R)-1 and (1S,5R)-2 basically occurring in the process. followed our previous synthesis of their corresponding enantiomers, (1R,5S)-1 and (1R,5S)-2, respectively,4) Key words: litseaverticillol; enantioselective synthesis; except that (R)-4-benzyloxazolidin-2-one was employed sesquiterpenoid; anti-HIV as the source of chirality, instead of its (S)-form used in the previous synthesis. Homogeranic -

Lecture 3: Stereochemistry and Drugs Key Objectives: 1

Lecture 3: Stereochemistry and drugs Key objectives: 1. Be able to explain the role of stereochemistry in drug action or metabolism 2. Be able to identify a chiral center (or centers) in a drug 3. Be able to explain the difference between enantiomers and diastereomers Value of chirality and stereochemistry: Chirality as expressed through stereoisomers increases the specificity of molecule recognition and signaling. Like a key in a lock, or a hand in a glove. Some useful definitions: Chirality (and chiral centers): An object (such as a molecule) that is asymmetric and therefore not superimposable on its own image. Chiral centers are the most common features within molecules that give rise to chirality. Stereoisomer: A molecule that possesses at least one chiral center (or center of chirality). Enantiomers: A type of stereoisomer that exists in mirror image forms. See Figure 1. Diastereomers: A type of stereoisomer that possesses more than one chiral center. Stereospecific: A term used to describe a stereochemical property that one isomer possesses but the other does not. For example, the stereospecific metabolism of the S-enantiomer of a compound by an enzyme but the R-enantiomer is not metabolized by that enzyme. Stereoselective: A term used to describe a stereochemical property that is shared by both stereoisomers, but the property is greater in one isomer than the other. For example, the stereoselective binding of the R-enantiomer for a receptor indicates that the S-enantiomer also binds but not as avidly as the R-enantiomer. Enantiomers Figure 1: For enantiomers, many times we use the example of our left and right hands to demonstrate their asymmetry. -

Diastereomers Diastereomers

Diastereomers Diastereomers: Stereoisomers that are not mirror images. enantiomer (R) (S) (S) (R) diastereomers diastereomer diastereomer enantiomer (R) (S) (R) (S) Diastereomers Diastereomers: Stereoisomers that are not mirror images. (R) enantiomer (S) (S) (R) diastereomer To draw the enantiomer of a molecule with chiral centers, invert stereochemistry at all chiral centers. (R) To draw a diastereomer of a molecule (R) with chiral centers, invert stereochemistry at only some chiral centers. Meso Compounds Meso: A molecule that contains chiral centers, but is achiral. 3 Are these molecules chiral? (R) (S) (These are diff eren t f rom th e 3 molecules I just showed; they have 2 -Cl’s, rather than 1 -Cl & 1 -OH. enantiomer (R) (S) (R) (S) These molecules are chiral mirror images of one another. (R,R) and (S,S) are not the same. Meso Compounds Meso: A molecule that contains chiral centers, but is achiral. 3 enantiomer ? (R) (S) (S) (R) no! 3 same molecule! enantiomer (R) (S) (R) (S) Meso Compounds Meso: A molecule that contains chiral centers, but is achiral. 3 enantiomer ? (R) (S) (S) (R) no! 3 same molecule! If a molecule • contains the same number of (R) and (S) stereocenters, and • those stereocenters have identical groups attached, then the molecule is achiral and meso. Meso Compounds Meso: A molecule that contains chiral centers, but is achiral. 3 same molecule (R) (S) (S) (R) 3 meso diastereomers meso diastereomer diastereomer enantiomer (R) (S) (R) (S) chiral chiral Properties of Enantiomers Most physical properties of enantiomers are identical. diethyl-(R,R)-tartrate diethyl-(S,S)-tartrate boiling point 280 °C 280 °C melting point 19 °C 19 °C density 1.204 g/mL 1.204 g/mL refractive index 1.447 1.447 i.e., chirality does not affect most physical properties. -

Enantiomers & Diastereomers

Chapter 5 Stereochemistry Chiral Molecules Ch. 5 - 1 1. Chirality & Stereochemistry An object is achiral (not chiral) if the object and its mirror image are identical Ch. 5 - 2 A chiral object is one that cannot be superposed on its mirror image Ch. 5 - 3 1A. The Biological Significance of Chirality Chiral molecules are molecules that cannot be superimposable with their mirror images O O ● One enantiomer NH causes birth defects, N O the other cures morning sickness O Thalidomide Ch. 5 - 4 HO NH HO OMe Tretoquinol OMe OMe ● One enantiomer is a bronchodilator, the other inhibits platelet aggregation Ch. 5 - 5 66% of all drugs in development are chiral, 51% are being studied as a single enantiomer Of the $475 billion in world-wide sales of formulated pharmaceutical products in 2008, $205 billion was attributable to single enantiomer drugs Ch. 5 - 6 2. Isomerisom: Constitutional Isomers & Stereoisomers 2A. Constitutional Isomers Isomers: different compounds that have the same molecular formula ● Constitutional isomers: isomers that have the same molecular formula but different connectivity – their atoms are connected in a different order Ch. 5 - 7 Examples Molecular Constitutional Formula Isomers C4H10 and Butane 2-Methylpropane Cl Cl C3H7Cl and 1-Chloropropane 2-Chloropropane Ch. 5 - 8 Examples Molecular Constitutional Formula Isomers CH O CH C H O OH and 3 3 2 6 Ethanol Methoxymethane O OCH and 3 C H O OH 4 8 2 O Butanoic acid Methyl propanoate Ch. 5 - 9 2B. Stereoisomers Stereoisomers are NOT constitutional isomers Stereoisomers have their atoms connected in the same sequence but they differ in the arrangement of their atoms in space. -

Chapter 4: Stereochemistry Introduction to Stereochemistry

Chapter 4: Stereochemistry Introduction To Stereochemistry Consider two of the compounds we produced while finding all the isomers of C7H16: CH3 CH3 2-methylhexane 3-methylhexane Me Me Me C Me H Bu Bu Me Me 2-methylhexane H H mirror Me rotate Bu Me H 2-methylhexame is superimposable with its mirror image Introduction To Stereochemistry Consider two of the compounds we produced while finding all the isomers of C7H16: CH3 CH3 2-methylhexane 3-methylhexane H C Et Et Me Pr Pr 3-methylhexane Me Me H H mirror Et rotate H Me Pr 2-methylhexame is superimposable with its mirror image Introduction To Stereochemistry Consider two of the compounds we produced while finding all the isomers of C7H16: CH3 CH3 2-methylhexane 3-methylhexane .Compounds that are not superimposable with their mirror image are called chiral (in Greek, chiral means "handed") 3-methylhexane is a chiral molecule. .Compounds that are superimposable with their mirror image are called achiral. 2-methylhexane is an achiral molecule. .An atom (usually carbon) with 4 different substituents is called a stereogenic center or stereocenter. Enantiomers Et Et Pr Pr Me CH3 Me H H 3-methylhexane mirror enantiomers Et Et Pr Pr Me Me Me H H Me H H Two compounds that are non-superimposable mirror images (the two "hands") are called enantiomers. Introduction To Stereochemistry Structural (constitutional) Isomers - Compounds of the same molecular formula with different connectivity (structure, constitution) 2-methylpentane 3-methylpentane Conformational Isomers - Compounds of the same structure that differ in rotation around one or more single bonds Me Me H H H Me H H H H Me H Configurational Isomers or Stereoisomers - Compounds of the same structure that differ in one or more aspects of stereochemistry (how groups are oriented in space - enantiomers or diastereomers) We need a a way to describe the stereochemistry! Me H H Me 3-methylhexane 3-methylhexane The CIP System Revisited 1. -

Distinction of Enantiomers by NMR

REVIEWS Disinction of enantiomers by NMR spectroscopy using chiral orienting media Burkhard Luy Abstract | NMR spectroscopy is a very important analytical tool in modern organic and inorganic chemistry. Next to the identification of molecules and their structure determination, it is also used for the distinction of enantiomers and the measurement of enantiomeric purity. This article gives a brief review of the techniques being developed for enantiomeric differentiation by virtue of chiral alignment media and their induction of enantiomerically dependent anisotropic NMR parameters like residual dipolar couplings. An overview of existing chiral alignment media, a brief introduction into the basic theory and measurement of the various anisotropic parameters, and several example applications are given. 1. Introduction valuable compounds one doesn’t necessarily want to NMR spectroscopy is one of the most important irreversibly modify the substance. analytical tools in modern organic and inorganic Another possibility for the distinction of chemistry as it is the only tool that allows the enantiomers is the orientation of the molecule of determination of molecular structures at atomic interest in a so-called chiral alignment medium. resolution in solution. It is used to identify the In this case, the molecule is partially aligned constitution, conformation and configuration and anisotropic NMR parameters like residual of countless molecules every day. However, the quadrupolar couplings, residual dipolar couplings magnetic field used for the induction of the Zeeman and residual chemical shift anisotropy can be splitting is per se achiral so that enantiomers measured2–4. As the orientation in a chiral have identical properties and therefore identical alignment medium is different for the two NMR spectra. -

Biocatalysis at Extreme Temperatures: Enantioselective Synthesis of Both Enantiomers of Mandelic Acid by Transesterification

catalysts Article Biocatalysis at Extreme Temperatures: Enantioselective Synthesis of both Enantiomers of Mandelic Acid by Transesterification Catalyzed by a ◦ Thermophilic Lipase in Ionic Liquids at 120 C Jesús Ramos-Martín, Oussama Khiari, Andrés R. Alcántara * and Jose María Sánchez-Montero * Department of Chemistry in Pharmaceutical Sciences, Pharmacy Faculty, Complutense University of Madrid (UCM), Ciudad Universitaria, Plaza de Ramon y Cajal, s/n., 28040 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] (J.R.-M.); [email protected] (O.K.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (A.R.A.); [email protected] (J.M.S.-M.); Tel.: +34-91-394-1820 (A.R.A.); +34-91-394-1839 (J.M.S.-M.) Received: 15 August 2020; Accepted: 11 September 2020; Published: 14 September 2020 Abstract: The use of biocatalysts in organic chemistry for catalyzing chemo-, regio- and stereoselective transformations has become an usual tool in the last years, both at lab and industrial scale. This is not only because of their exquisite precision, but also due to the inherent increase in the process sustainability. Nevertheless, most of the interesting industrial reactions involve water-insoluble substrates, so the use of (generally not green) organic solvents is generally required. Although lipases are capable of maintaining their catalytic precision working in those solvents, reactions are usually very slow and consequently not very appropriate for industrial purposes. Increasing reaction temperature would accelerate the reaction rate, but this should require the use of lipases from thermophiles, which tend to be more enantioselective at lower temperatures, as they are more rigid than those from mesophiles. Therefore, the ideal scenario would require a thermophilic lipase capable of retaining high enantioselectivity at high temperatures. -

Chirality: the Handedness of Molecules

06 Chirality: The Handedness of Molecules Tartaric acid is found in grapes and other fruits, both free and as its salts (see Section 6.4B). Inset: A model of tartaric acid. (© fatihhoca/iStockphoto) KEY QUESTIONS 6.1 What Are Stereoisomers? 6.9 What Is the Significance of Chirality in the 6.2 What Are Enantiomers? Biological World? 6.3 How Do We Designate the Configuration of a 6.10 How Can Enantiomers Be Resolved? Stereocenter? HOW TO 6.4 What Is the 2n Rule? 6.1 How to Draw Enantiomers 6.5 How Do We Describe the Chirality of 6.2 How to Determine the R & S Configuration Cyclic Molecules with Two Stereocenters? without Rotating the Molecule 6.6 How Do We Describe the Chirality 6.3 How to Determine Whether Two Compounds Are of Molecules with Three or More the Same, Enantiomers, or Diastereomers without Stereocenters? the Need to Spatially Manipulate the Molecule 6.7 What Are the Properties of Stereoisomers? 6.8 How Is Chirality Detected in the CHEMICAL CONNECTIONS Laboratory? 6A Chiral Drugs IN THIS CHAPTER, we will explore the relationships between three-dimensional ob- jects and their mirror images. When you look in a mirror, you see a reflection, or mirror Mirror image The reflection image, of yourself. Now, suppose your mirror image becomes a three-dimensional object. of an object in a mirror. 167 168 CHAPTER 6 Chirality: The Handedness of Molecules We could then ask, “What is the relationship between you and your mirror image?” By relationship, we mean “Can your reflection be superposed on the original ‘you’ in such a way that every detail of the reflection corresponds exactly to the original?” The answer is that you and your mirror image are not superposable. -

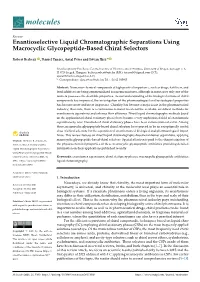

Enantioselective Liquid Chromatographic Separations Using Macrocyclic Glycopeptide-Based Chiral Selectors

molecules Review Enantioselective Liquid Chromatographic Separations Using Macrocyclic Glycopeptide-Based Chiral Selectors Róbert Berkecz ,Dániel Tanács, Antal Péter and István Ilisz * Interdisciplinary Excellence Centre, Institute of Pharmaceutical Analysis, University of Szeged, Somogyi u. 4, H-6720 Szeged, Hungary; [email protected] (R.B.); [email protected] (D.T.); [email protected] (A.P.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +36-62-545805 Abstract: Numerous chemical compounds of high practical importance, such as drugs, fertilizers, and food additives are being commercialized as racemic mixtures, although in most cases only one of the isomers possesses the desirable properties. As our understanding of the biological actions of chiral compounds has improved, the investigation of the pharmacological and toxicological properties has become more and more important. Chirality has become a major issue in the pharmaceutical industry; therefore, there is a continuous demand to extend the available analytical methods for enantiomeric separations and enhance their efficiency. Direct liquid chromatography methods based on the application of chiral stationary phases have become a very sophisticated field of enantiomeric separations by now. Hundreds of chiral stationary phases have been commercialized so far. Among these, macrocyclic glycopeptide-based chiral selectors have proved to be an exceptionally useful class of chiral selectors for the separation of enantiomers of biological and pharmacological impor- tance. This review focuses on direct liquid chromatography-based enantiomer separations, applying Citation: Berkecz, R.; Tanács, D.; macrocyclic glycopeptide-based chiral selectors. Special attention is paid to the characterization of Péter, A.; Ilisz, I. Enantioselective the physico-chemical properties of these macrocyclic glycopeptide antibiotics providing detailed Liquid Chromatographic Separations information on their applications published recently. -

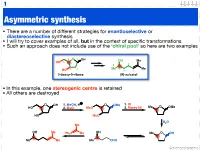

Asymmetric Synthesis

1 Asymmetric synthesis • There are a number of different strategies for enantioselective or diastereoselective synthesis • I will try to cover examples of all, but in the context of specific transformations • Such an approach does not include use of the ‘chiral pool’ so here are two examples 4 O 1 OH OH Me HO 5 5 2 3 2 Me 4 Me HO 3 1 2-deoxy-D-ribose (R)-sulcatol • In this example, one stereogenic centre is retained • All others are destroyed O OH 1. MeOH, H O OMe 1. KI HO 2. MsCl MsO 2. Raney Ni Me O OMe HO MsO H2O Me OH Me OH Ph3P Me Me O OH Me Me Me CHO Advanced organic 2 ‘Chiral pool’ II Me Me remove OH Me Me stereogenic 3 steps O O centre HO 2 4 OH PCC 3 O OH O O 6 OH HO 1 O 5 OTBDPS OTBDPS D-mannose BnO O BnO O addition of 1. NaBH protecting groups overall retention of 4 stereochemistry 2. Tf2O stereoselective Me 1. TBAF Me Me reduction Me 2. PCC Me Me O O O 3. Ph P=CHCHO NaN O 3 O 3 O N3 N3 OTf OTBDPS OTBDPS BnO O CHO BnO O BnO O Pd / C hydrogenolysis of benzyl (Bn) group & H reductive amination of resultant 2 aldehyde Me HO two step reversal of Me O 2 1 stereogenic centre reduction 1. H2, Pd / C, H of alkene & H H 3 O N 2. TFAA azide HO 4 N followed by reductive H 6 amination BnO O 5 H HO swainsonine • In this example three stereogenic centres are retained • One stereogenic centre undergoes multiple inversion -- but overall it is retained Advanced organic 3 Stereoselective reactions of alkenes • Alkenes are versatile functional groups that, as we shall see, present plenty of scope for the introduction of stereochemistry • Hydroboration permits the selective introduction of boron (surprise), which itself can undergo a wide-range of stereospecific reactions Substrate control Me H H Me H H Me 1. -

Separation of Stereoisomers Resolution of Racemic Mixtures the Separation of a Racemic Mixture Into the Individual Pure Enantiomers Is Called Resolution

Separation of Stereoisomers Resolution of Racemic Mixtures The separation of a racemic mixture into the individual pure enantiomers is called resolution. Since enantiomers have identical physical properties, such as solubility, boiling point and chromatographic retention time, they can not be resolved by common physical techniques such as crystallization, distillation or basic chromatography. However, diastereomers have different physical properties and can be separated by conventional physical techniques, a difference commonly exploited in resolution of racemic mixtures by placing the racemate in a chiral environment to 11:06 AM initiate diastereomeric interactions. 1 Resolution of Racemic Mixtures Conversion of enantiomers to diastereomers 11:06 AM 2 Separation of Stereoisomers Resolution of Racemic Mixtures All methods for separating or characterizing enantiomers exploit the formation of diastereomeric interactions. Although the interactions that create diastereomers out of enantiomers are commonly: (i) Ionic interactions or (ii) Covalent interactions, However, this is not a strict requirement for separations. Weaker, non-covalent complexes or interactions based on van Der Waal or hydrogen bonding interactions are often 11:06 AM discriminating enough to allow separation of enantiomers. 3 Methods of Resolving Racemic Mixtures Summary The four general strategies that take advantage of the formation of diastereomeric interactions to separate a racemic mixture or enantiomerically enriched mixture are: a) Formation of diastereomeric salts with an enantiopure resolving agent. b) Formation of diastereomeric compounds with an enantiopure resolving agent. c) Enzymatic resolution using an appropriate enzyme. d) Use of chiral stationary phases for chromatographic resolution of racemic mixtures. 11:06 AM 4 Resolution of Racemic Mixtures Diastereomeric Salt Formation In 1849, Louis Pasteur, in his pioneering work, was able to isolate the enantiomers of tartaric acid because they crystallize from solution as crystals with differing symmetry and shape. -

Stereochemistry Three-Dimensional Arrangement of Atoms (Groups) in Space

Chapter 9: Stereochemistry three-dimensional arrangement of atoms (groups) in space Stereoisomers: molecules with the same connectivity but different arrangement of atoms (groups) in space H C CH 3 3 H3C H H H H CH3 cis-1,2-dimethylcyclopropane trans-1,2-dimethylcyclopropane H H H CH3 H3C CH3 H3C H cis-2-butene trans-2-butene geometric isomers (diastereomers) 1 Enantiomers: non-superimposable mirror image isomers. Enantiomers are related to each other much like a right hand is related to a left hand Enantiomers have identical physical properties, i.e., bp, mp, etc. Chirality (from the Greek word for hand). Enantiomers are said to be chiral. Molecules are not chiral if they contain a plane of symmetry: a plane that cuts a molecule in half so that one half is the mirror image of the other half. Molecules (or objects) that possess a mirror plane of symmetry are superimposable on their mirror image and are termed achiral. A carbon with four different groups results in a chiral molecule and is refered to as a chiral or asymmetric or stereogenic center. 2 symmetry plane O H H H C O C C H Achiral H H O Not a symmetry plane O H H OH CH3 Chiral H C O C C H H H O Chiral center (stereogenic, asymmetric) Optical Rotation: molecules enriched in an enantiomer will rotate plane polarized light are are said to be optiically active. The optical rotation is dependent upon the substance, the concentration, the path length through the sample and the wavelength of light.