Shaped by Function: Boston's Historic Warehouses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Heart of Boston Stunning Waterfront Location

IN THE HEART OF BOSTON STUNNING WATERFRONT LOCATION OWNED BY CSREFI INDEPENDENCE WHARF BOSTON INC. independence wharf 470 atlantic avenue • Boston, MA Combining a Financial District address with a waterfront location and unparalleled harbor views, Independence Wharf offers tenants statement-making, first-class office space in a landmark property in downtown Boston. The property is institutionally owned by CSREFI INDEPENDENCE WHARF BOSTON INC., a Delaware Corporation, which is wholly owned by the Credit Suisse Real Estate Fund International. Designed to take advantage of its unique location on the historic Fort Point Channel, the building has extremely generous window lines that provide tenants with breathtaking water and sky line views and spaces flooded with natural light. Independence Wharf’s inviting entrance connects to the Harborwalk, a publicly accessible wharf and walkway that provides easy pedestrian access to the harbor and all its attractions and amenities. Amenities abound inside the building as well, including “Best of Class” property management services, on-site conference center and public function space, on-site parking, state-of-the-art technical capabilities, and a top-notch valet service. OM R R C AR URPHY o HE R C N HI IS CI ASNEY el CT ST v LL R TI AL ST CT L De ST ESTO ST THAT CHER AY N N. ST WY Thomas P. O’Neill CA NORTH END CLAR ST BENN K NA ST E Union Wharf L T Federal Building CAUSEW N N WASH ET D ST MA LY P I ST C T NN RG FR O IE T IN T ND ST ST S FL IN PR PO ST T EE IN T RT GT CE ST LAND ST P ON OPER ST ST CO -

The Boston Tea Party Grade 4

Sample Item Set The Boston Tea Party Grade 4 Standard 7 – Government and Political Systems Students explain the structure and purposes of government and the foundations of the United States’ democratic system using primary and secondary sources. 4.7.2 Explain the significance of key ideas contained in the Declaration of Independence, the United States Constitution, and the Bill of Rights SOCIAL STUDIES SAMPLE ITEM SET GRADE 4 1 Sample Item Set The Boston Tea Party Grade 4 Use the three sources and your knowledge of social studies to answer questions 1–3. Source 1 Boston Tea Party Engraving This engraving from 1789 shows the events of December 16, 1773. Dressed as American Indians, colonists dumped nearly 90,000 pounds of British East India Company tea into Boston Harbor in protest against the Tea Act. SOCIAL STUDIES SAMPLE ITEM SET GRADE 4 2 Sample Item Set The Boston Tea Party Grade 4 Source 2 Writing of the Declaration of Independence This picture shows Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson writing the Declaration of Independence in 1776. Thomas Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence with help from other members of the Continental Congress. SOCIAL STUDIES SAMPLE ITEM SET GRADE 4 3 Sample Item Set The Boston Tea Party Grade 4 Source 3 Timeline of Events Leading to American Revolution Year Event 1764 Britian passes the Sugar Act on Colonists. 1765 Britian passes the Stamp Act on Colonists. 1767 Britian passes Townshend Acts on Colonists. 1770 Boston Massacre occurs when the British Army kills five Colonists. 1773 Colonists protest at the Boston Tea Party. -

Boston Harbor National Park Service Sites Alternative Transportation Systems Evaluation Report

U.S. Department of Transportation Boston Harbor National Park Service Research and Special Programs Sites Alternative Transportation Administration Systems Evaluation Report Final Report Prepared for: National Park Service Boston, Massachusetts Northeast Region Prepared by: John A. Volpe National Transportation Systems Center Cambridge, Massachusetts in association with Cambridge Systematics, Inc. Norris and Norris Architects Childs Engineering EG&G June 2001 Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing the burden, to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (From - To) 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER 5b. GRANT NUMBER 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER 5e. TASK NUMBER 5f. WORK UNIT NUMBER 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER 9. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. -

State of the Park Report, Salem Maritime National Historic Site

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior STATE OF THE PARK REPORT Salem Maritime National Historic Site Salem, Massachusetts April 2013 National Park Service 2013 State of the Park Report for Salem Maritime National Historic Site State of the Park Series No. 7. National Park Service, Washington, D.C. On the cover: The tall ship, Friendship of Salem, the Custom House, Hawkes House, and historic wharves at Salem Maritime Na- tional Historic Site. (NPS) Disclaimer. This State of the Park report summarizes the current condition of park resources, visitor experience, and park infra- structure as assessed by a combination of available factual information and the expert opinion and professional judgment of park staff and subject matter experts. The internet version of this report provides the associated workshop summary report and additional details and sources of information about the findings summarized in the report, including references, accounts on the origin and quality of the data, and the methods and analytic approaches used in data collection and assessments of condition. This report provides evaluations of status and trends based on interpretation by NPS scientists and managers of both quantitative and non-quantitative assessments and observations. Future condition ratings may differ from findings in this report as new data and knowledge become available. The park superintendent approved the publication of this report. SALEM MARITIME NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE CONTENTS Executive Summary 1 State of the Park Summary Table 3 Summary of Stewardship Activities and Key Accomplishments to Maintain or Improve Priority Resource Condition: 5 Key Issues and Challenges for Consideration in Management Planning 6 Chapter 1. -

V. Inland Ports Planningand Cargos Handling Opera Tion*

V. INLAND PORTS PLANNINGAND CARGOS HANDLING OPERA TION* Inland Ports Planning General The term inland waterway port or an inland waterway terminal conveys the idea of an end point. Indeed, traditionally, ports were perceived as end points of the transport system whereby water transport of cargoeswas either originated or terminated. However, from a broader point of view, the one encompassingthe so-called "c~ain of transport", ports or terminals are neither starting nor ending points; they are simply the intermediate points where cargoesare transferred between the links in the transport chain. The emphasis on the transfer function in this introductory section is made since: (a) Ports' main function is to move the cargo and to avoid accumulating and damaging it; (b) In order to efficiently fulfill their transfer function, ports or terminals have to possess convenient access(rail and road) to the connecting modes of transport. broader definition ora port seems especially appropriate for our discussion on inland waterway transportation (IWT). IWT is part of the domestic transportation system which also includes rail and road transpiration. IWT, unlike rail and road transportation, can oQly connectpoints which are locatea on the waterway network. Consequently, in most caSes othercomplementary land transportation modes are required for the entire origin-to-destinationtransport. In other words, since in most casesthe IWT cargo does not originate or terminate atthe port site itself, the main function of the inland port is to transfer the cargo between IWTvessels, trains, and trucks. The inland ports are important for the economic development of a country. The inland port, therail, the road and the seaport are equally important. -

Potomac River Transporation Plan.Indd

Potomac River Transportation Framework Plan Washington DC, Virginia, Maryland Water transportation is the most economical, energy effi cient and environmentally friendly transportation that exists for major cities today. The vast river network that was the original lifeblood of the Washington, DC region remains underutilized. The Potomac River Transportation Framework Plan is a comprehensive master plan outlining a water based transportation network on the Potomac and Anacostia Rivers in Washington, DC, Maryland and Virginia, for commuters, tourists and the federal government (defense and civilian evacuations). This plan outlines an enormous opportunity to expand the transportation network at a fraction of the cost (both in dollars and environmental impact) of other transportation modes. The plan includes intermodal connections to the existing land based public transportation system. See Detail Plan GEORGETOWN REGIONAL PLAN KENNEDY CENTER RFK STADIUM NATIONAL MALL THE WHARF BASEBALL The plan to the left GEORGETOWN STADIUM NAVY YARD PENTAGON BUZZARD POINT/ SOCCER STADIUM POPLAR POINT illustrates the reach of FORT MCNAIR JBAB the transporation plan KENNEDY CENTER that includes Virginia, NATIONAL AIRPORT RFK STADIUM JBAB / ST. ELIZABETHS SOUTH Maryland, and the DAINGERFIELD ISLAND NATIONAL MALL GENON SITE District of Columbia, CANAL CENTER ROBINSON TERMINAL NORTH fully integrated with THE OLD TOWN- KING STREET existing land based WHARF ROBINSON TERMINAL SOUTH BASEBALL PENTAGON STADIUM NAVY YARD JONES POINT transporation. NATIONAL HARBOR POPLAR POINT BUZZARD POINT/SOCCER STADIUM FORT MCNAIR JBAB A TERMINAL ‘A’ Both Plans illustrate B TERMINAL ‘B’ C TERMINAL ‘C’ potential routes and landings for D TERMINAL ‘D’ MOUNT VERNON FORT WASHINGTON Commuters, Tourists NATIONAL AIRPORT and the Federal JBAB / ST. -

Marinas of Anne Arundel County

Marina Inventory Of Anne Arundel County 2018 Office of Planning & Zoning Long Range Planning Division Marina Inventory Of Anne Arundel County July 2018 Anne Arundel County Office of Planning and Zoning Long Range Planning Division ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Office of Planning and Zoning Philip R. Hager, Planning and Zoning Officer Lynn Miller, Assistant Planning and Zoning Officer Project Team Long Range Planning Division Cindy Carrier, Planning Administrator Mark Wildonger, Senior Planner Patrick Hughes, Senior Planner Andrea Gerhard, Planner II Special Thanks to VisitAnnapolis.org for the use of the cover photo showing Herrington Harbor. Table of Contents Background Marinas Commercial Marinas Community Marinas Impacts of Marinas Direct Benefit Census Data and Economic Impact Other Waterfront Sites in the County Appendix A – Listing of Marinas in Anne Arundel County, 2018 Appendix B – Location Maps of Marinas in Anne Arundel County, 2018 Office of Planning & Zoning Long Range Planning Division Marinas of Anne Arundel County Background Anne Arundel County has approximately 533 miles of shoreline along the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries. This resource provides the opportunity for the marine industry to flourish, providing services to the commercial and recreational boaters. In 1980, the first Boating and Marina Study was completed in the County. At that time, the County had 57 marinas and 1,767 boat slips.1 Since that time the County has experienced significant growth in all aspects of its economy including the marine industry. As of June 2018, there are a total of 303 marinas containing at total of 12,035 boat slips (Table 1). This report was prepared as an update to the 1997 and 2010 marina inventories2 and includes an updated inventory and mapping of marinas in the County. -

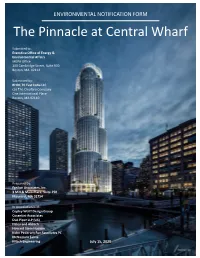

Mepa Environmental Notification Form

ENVIRONMENTAL NOTIFICATION FORM The Pinnacle at Central Wharf Submitted to: Executive Office of Energy & Environmental Affairs MEPA Office 100 Cambridge Street, Suite 900 Boston, MA 02114 Submitted by: RHDC 70 East India LLC c/o The Chiofaro Company One International Place Boston, MA 02110 Prepared by: Epsilon Associates, Inc. 3 Mill & Main Place, Suite 250 Maynard, MA 01754 In Association with: Copley Wolff Design Group Cosentini Associates DLA Piper LLP (US) Haley and Aldrich Howard Stein Hudson Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates PC McNamara Salvia Nitsch Engineering July 15, 2020 July 15, 2020 PRINCIPALS Subject: The Pinnacle at Central Wharf Theodore A Barten, PE Environmental Notification Form Margaret B Briggs Massachusetts Environmental Policy Act (MEPA) Dale T Raczynski, PE Cindy Schlessinger Dear Interested Party: Lester B Smith, Jr Robert D O’Neal, CCM, INCE On behalf of the Proponent, RHDC 70 East India LLC, I am pleased to send you the Michael D Howard, PWS enclosed Environmental Notification Form (ENF) for the redevelopment of the 1.32-acre Douglas J Kelleher Boston Harbor Garage site in Boston’s Downtown Waterfront District. The project is AJ Jablonowski, PE located at 70 East India Row (a/k/a 270 Atlantic Avenue) in the City of Boston. Stephen H Slocomb, PE The Proponent expects that the ENF will be noticed in the Environmental Monitor on July David E Hewett, LEED AP 22, 2020 and that comments will be due by August 11, 2020. Comments can be submitted Dwight R Dunk, LPD online at: David C Klinch, PWS, PMP Maria B Hartnett https://eeaonline.eea.state.ma.us/EEA/PublicComment/Landing/ or sent to: ASSOCIATES Secretary Kathleen A. -

Boston Nps Map A5282872-8D05

t t E S S G t t B S B d u t D t a n n I S r S r k t l t e e R North S l o r e s To 95 t e o t c H B l o t m i t S m t S n l f b t t n l a le h S S u S u R t c o o t s a S n t E n S C T a R m n t o g V e u l S I s U D e M n n R l s E t M i e o F B V o e T p r s S n x e in t t P p s u r e l h H i L m e r u S C IE G o a S i u I C h u q e L t n n r R E L P H r r u n o T a i el a t S S k e S 1 R S w t gh C r S re t t 0 R 0 0.1 Kilometer 0.3 F t S t e M S Y a n t O r r E e M d u M k t t T R Phipps n S a S S e r H H l c i t Bunker Hill em a Forge Shop V D e l n t C o i o d S nt ll I 0 0.1 Mile 0.3 Street o o Monument S w h o n t e P R c e P S p Cemetery S W e M t IE S o M r o e R Bunker Hill t r t n o v C A t u R A s G S m t s y 9 C S h p a V e t q e t Community u n V I e e s E W THOMPSON S a t W 1 r e e s c y T s College e t r t e SQUARE i S v n n n d t Gate 4 t o S S P r A u w Y n S W t o i IE t a t n t o a lla L e R W c 5 S s t n e Boston Marine Society M C C S t i y n e t t o 8 r a a y h a r t e f e e e m t S L in t re l l A S o S S u C t S a em n P m o d t Massachusetts f h t w S S n a 1 i COMMUNITY u o t m S p r n S s h b e Commandant’s Korean War o M S i u COLLEGE t n t S t p S O S t b il c M TRAIN ING FIELD House Veterans Memorial d R l e D u d i n C R il n ti W p P t d s R o o S Y g u a u m u d USS Constitution i A sh t M r o D n W O in on h t th m t o SHIPYARD g g i er s S a n n lw Museum O P a M n i o a l W t U f n t n i E C PARK y B O Ly o o e n IE s n r v S t m D K a n H W d R N d e S S R y 2 S e t 2 a t 7 s R IG D t Y r Building -

Identification of Massachusetts Freight Issues and Priorities

Identification of Massachusetts Freight Issues and Priorities Prepared for the Massachusetts Freight Advisory Council By Massachusetts Highway Department Argeo Paul Cellucci Jane Swift Kevin J. Sullivan Matthew J. Amorello Governor Lieutenant Governor Secretary Commissioner And Louis Berger and Associates Identification of Massachusetts Freight Issues and Priorities Massachusetts Freight Advisory Council Chairman Robert Williams Project Manager and Report Author Mark Berger, AICP Project Support (Consultant) Adel Foz Wendy Fearing Chris Orphanides Rajesh Salem The preparation of this document was supported and funded by the Massachusetts Highway Department and Federal Highway Administration through Agreement SPR 97379. November 1999 Identification of Massachusetts Freight Issues and Priorities Table of Contents CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................................1-1 Purpose...........................................................................................................................................................1-1 Massachusetts Freight Advisory Council.........................................................................................................1-1 Contents of Report..........................................................................................................................................1-1 CHAPTER 2: SOLICITATION OF FREIGHT ISSUES..................................................................................2-1 -

Maritime Transportation Research and Education Center Tier 1 University Transportation Center U.S. Department of Transportation

MARITIME TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH AND EDUCATION CENTER TIER 1 UNIVERSITY TRANSPORTATION CENTER U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION Transit-Oriented Development and Ports: National Analysis across the United States and a Case Study of New Orleans Project Start Date: October 2013 Project End Date: September 2017 Principal Investigator: John L. Renne, Ph.D., AICP Director and Associate Professor, Center for Urban and Environmental Solutions School of Urban and Regional Planning Florida Atlantic University Building 44, Room 284 777 Glades Road Boca Raton, Florida 33431 561-297-4281 [email protected] Honorary Research Associate Transport Studies Unit, School of Geography and the Environment University of Oxford Final Report Date: November 2017 FINAL RESEARCH REPORT Prepared for: Maritime Transportation Research and Education Center University of Arkansas 4190 Bell Engineering Center Fayetteville, AR 72701 479-575-6021 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This material is based upon work supported by the U.S. Department of Transportation under Grant Award Number DTRT13-G-UTC50. The work was conducted through the Maritime Transportation Research and Education Center (MarTREC) at the University of Arkansas. In partnership with and as a member of the MarTREC consortium, this project was funded through the University of New Orleans Transportation Institute, where Dr. John L. Renne was employed until the end of 2015. Dr. Renne would like to acknowledge Tara Tolford and Estefania Mayorga for their efforts on the data analysis and assistance with the report. He is grateful to all of the interviewees who donated their time for the benefit of this study. Finally, Dr. Renne wishes to thank James Amdal for his expertise and assistance on this project. -

Director of Airline Route Development

About Massport The Massachusetts Port Authority (Massport) is an independent public authority in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts that is governed by a seven member Board. Massport is financially self-sustaining and contributes to the regional economy through the operation of three airports—Boston Logan International Airport, Hanscom Field and Worcester Regional Airport; the Port of Boston’s cargo and cruise facilities; and property management/real estate development in Boston. Massport’s mission is to connect Massachusetts and New England to the world, safely, securely and efficiently, never forgetting our commitment to our neighbors who live and work around our ports and facilities. Massport is an integral component of a national and worldwide transportation network, operating New England’s most important air and sea transportation facilities that connect passengers and cargo with hundreds of markets around the globe. Massport continually works to modernize its infrastructure to enhance customer service, improve operations and optimize land use, and has invested more than $4 billion over the past decade in coordination with its transportation partners. Massport also strives to be a good neighbor closer to home. Working in concert with government, community and civic leaders throughout Massachusetts and New England, Massport is an active participant in efforts that improve the quality of life for residents living near Massport’s facilities and who make sacrifices every day so that Massport can deliver important transportation services to families and businesses throughout New England. Boston Logan International Airport Boston Logan International Airport (BOS) is New England’s largest transportation center and an economic engine that generates $13.3 billion in economic activity each year.