Calgary Highlanders and the Walcheren Causeway Battle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dynamic Control of Salt Intrusion in the Mark-Vliet River System, the Netherlands

Water Resour Manage (2011) 25:1005–1020 DOI 10.1007/s11269-010-9738-1 Dynamic Control of Salt Intrusion in the Mark-Vliet River System, The Netherlands Denie C. M. Augustijn · Marcel van den Berg · Erik de Bruine · Hans Korving Received: 11 January 2010 / Accepted: 8 November 2010 / Published online: 11 January 2011 © The Author(s) 2011. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract The Volkerak-Zoom Lake is an enclosed part of the estuarine delta in the southwest of the Netherlands and exists as such since 1987. The current freshwater lake experienced a deterioration in water and ecological quality. Espe- cially cyanobacteria are a serious problem. To solve this problem it is proposed to reintroduce salt water and tidal dynamics in the Volkerak-Zoom Lake. However, this will affect the water quality of the Mark-Vliet River system that drains into the lake. Each of the two branches of the Mark-Vliet River system is separated from the Volkerak-Zoom Lake by a lock and drainage sluice. Salt intrusion via the locks may hamper the intake of freshwater by the surrounding polders. Salt intrusion can be reduced by increasing the discharge in the river system. In this study we used the hydrodynamic SOBEK model to run different strategies with the aim to minimize the additional discharge needed to reduce chloride concentrations. Dynamic control of the sluices downstream and a water inlet upstream based on real-time chloride concentrations is able to generate the desired discharges required to maintain the chloride concentrations at the polder intake locations below the threshold level and D. -

The Story of the Military Museums

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2020-02 Treasuring the Tradition: The Story of the Military Museums Bercuson, David Jay; Keshen, Jeff University of Calgary Press Bercuson, D. J., & Keshen, J. (2020). Treasuring the Tradition: The story of the Military Museums. Calgary, AB: The University of Calgary Press. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/111578 book https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca TREASURING THE TRADITION: Treasuring the Tradition THE STORY OF THE MILITARY MUSEUMS The Story of the Military Museums by Jeff Keshen and David Bercuson ISBN 978-1-77385-059-7 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please Jeff Keshen and David Bercuson support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

The Quandary of Allied Logistics from D-Day to the Rhine

THE QUANDARY OF ALLIED LOGISTICS FROM D-DAY TO THE RHINE By Parker Andrew Roberson November, 2018 Director: Dr. Wade G. Dudley Program in American History, Department of History This thesis analyzes the Allied campaign in Europe from the D-Day landings to the crossing of the Rhine to argue that, had American and British forces given the port of Antwerp priority over Operation Market Garden, the war may have ended sooner. This study analyzes the logistical system and the strategic decisions of the Allied forces in order to explore the possibility of a shortened European campaign. Three overall ideas are covered: logistics and the broad-front strategy, the importance of ports to military campaigns, and the consequences of the decisions of the Allied commanders at Antwerp. The analysis of these points will enforce the theory that, had Antwerp been given priority, the war in Europe may have ended sooner. THE QUANDARY OF ALLIED LOGISTICS FROM D-DAY TO THE RHINE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Department of History East Carolina University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in History By Parker Andrew Roberson November, 2018 © Parker Roberson, 2018 THE QUANDARY OF ALLIED LOGISTICS FROM D-DAY TO THE RHINE By Parker Andrew Roberson APPROVED BY: DIRECTOR OF THESIS: Dr. Wade G. Dudley, Ph.D. COMMITTEE MEMBER: Dr. Gerald J. Prokopowicz, Ph.D. COMMITTEE MEMBER: Dr. Michael T. Bennett, Ph.D. CHAIR OF THE DEP ARTMENT OF HISTORY: Dr. Christopher Oakley, Ph.D. DEAN OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL: Dr. Paul J. -

Canadian Infantry Combat Training During the Second World War

SHARPENING THE SABRE: CANADIAN INFANTRY COMBAT TRAINING DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR By R. DANIEL PELLERIN BBA (Honours), Wilfrid Laurier University, 2007 BA (Honours), Wilfrid Laurier University, 2008 MA, University of Waterloo, 2009 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in History University of Ottawa Ottawa, Ontario, Canada © Raymond Daniel Ryan Pellerin, Ottawa, Canada, 2016 ii ABSTRACT “Sharpening the Sabre: Canadian Infantry Combat Training during the Second World War” Author: R. Daniel Pellerin Supervisor: Serge Marc Durflinger 2016 During the Second World War, training was the Canadian Army’s longest sustained activity. Aside from isolated engagements at Hong Kong and Dieppe, the Canadians did not fight in a protracted campaign until the invasion of Sicily in July 1943. The years that Canadian infantry units spent training in the United Kingdom were formative in the history of the Canadian Army. Despite what much of the historical literature has suggested, training succeeded in making the Canadian infantry capable of succeeding in battle against German forces. Canadian infantry training showed a definite progression towards professionalism and away from a pervasive prewar mentality that the infantry was a largely unskilled arm and that training infantrymen did not require special expertise. From 1939 to 1941, Canadian infantry training suffered from problems ranging from equipment shortages to poor senior leadership. In late 1941, the Canadians were introduced to a new method of training called “battle drill,” which broke tactical manoeuvres into simple movements, encouraged initiative among junior leaders, and greatly boosted the men’s morale. -

Ross Ellis Memorial Lecture Ross Ellis

Journal of Military and Strategic VOLUME 19, ISSUE 3 Studies Ross Ellis Memorial Lecture Ross Ellis: A Canadian Temperate Hero Geoffrey Hayes Lieutenant-Colonel Ross Ellis was a remarkable soldier who led the Calgary Highlanders, and later his community and province with distinction. Ellis had those powerful but elusive qualities of a leader, defined by a British doctor in 1945: the technical knowledge to lead, but also the moral equipment to inspire.1 This article has two purposes. First it explores briefly what kind of man the wartime Canadian Army sought for its commissioned leadership. It then draws upon the correspondence between Ross Ellis and his wife Marjorie to see how one remarkable soldier negotiated his first weeks in battle in the summer of 1944. These letters reveal how, with Marjorie’s encouragement, Ross Ellis sustained his own morale and nurtured 1 Emanuel Miller, “Psychiatric Casualties Among Officers and Men from Normandy: Distribution of Aetiological Factors.” The Lancet 245, no. 6343 (March 1945): pp. 364–66. ©Centre of Military and Strategic Studies, 2019 ISSN : 1488-559X VOLUME 19, ISSUE 3 a leadership style that would become legendary within the Calgary Highlanders community. Like so many others, Ross Ellis practiced a kind of temperate heroism2 a reaction not only to the idealized, heroic vision of officership in the First World War, but also to British and especially German representations of wartime leadership. The First World War cast a wide shadow over Ross Ellis’ generation. And although much changed between the two wars, there were still remarkable similarities in the way in which soldiers understood and endured the war. -

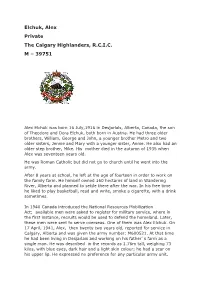

Elchuk, Alex Private the Calgary Highlanders, R.C.I.C. M – 39751

Elchuk, Alex Private The Calgary Highlanders, R.C.I.C. M – 39751 Alex Elchuk was born 16 July,1916 in Desjarlais, Alberta, Canada, the son of Theodore and Dora Elchuk, both born in Austria. He had three older brothers, William, George and John, a younger brother Metro and two older sisters, Jennie and Mary with a younger sister, Annie. He also had an older step brother, Mike. His mother died in the autumn of 1935 when Alex was seventeen years old. He was Roman Catholic but did not go to church until he went into the army. After 8 years at school, he left at the age of fourteen in order to work on the family farm. He himself owned 160 hectares of land in Wandering River, Alberta and planned to settle there after the war. In his free time he liked to play basketball, read and write, smoke a cigarette, with a drink sometimes. In 1940 Canada introduced the National Resources Mobilization Act; available men were asked to register for military service, where in the first instance, recruits would be used to defend the homeland. Later, these men were sent to serve overseas. One of them was Alex Elchuk. On 17 April, 1941, Alex, then twenty two years old, reported for service in Calgary, Alberta and was given the army number: M600521. At that time he had been living in Desjarlais and working on his father’ s farm as a single man. He was described in the records as 1.76m tall, weighing 73 kilos, with blue eyes, dark hair and a light skin colour; he had a scar on his upper lip. -

Making Lifelines from Frontlines; 1

The Rhine and European Security in the Long Nineteenth Century Throughout history rivers have always been a source of life and of conflict. This book investigates the Central Commission for the Navigation of the Rhine’s (CCNR) efforts to secure the principle of freedom of navigation on Europe’s prime river. The book explores how the most fundamental change in the history of international river governance arose from European security concerns. It examines how the CCNR functioned as an ongoing experiment in reconciling national and common interests that contributed to the emergence of Eur- opean prosperity in the course of the long nineteenth century. In so doing, it shows that modern conceptions and practices of security cannot be under- stood without accounting for prosperity considerations and prosperity poli- cies. Incorporating research from archives in Great Britain, Germany, and the Netherlands, as well as the recently opened CCNR archives in France, this study operationalises a truly transnational perspective that effectively opens the black box of the oldest and still existing international organisation in the world in its first centenary. In showing how security-prosperity considerations were a driving force in the unfolding of Europe’s prime river in the nineteenth century, it is of interest to scholars of politics and history, including the history of international rela- tions, European history, transnational history and the history of security, as well as those with an interest in current themes and debates about transboundary water governance. Joep Schenk is lecturer at the History of International Relations section at Utrecht University, Netherlands. He worked as a post-doctoral fellow within an ERC-funded project on the making of a security culture in Europe in the nineteenth century and is currently researching international environmental cooperation and competition in historical perspective. -

Cleijenborchse Courant

Zomereditie Cleijenborchse Courant 2019 Inhoud Voorwoord ......................................................................................................................................... 2 Brandveiligheid ................................................................................................................................... 3 Puzzel ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Kerkdiensten ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Kerkauto ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Van de Cliëntenraad ............................................................................................................................ 5 Zomermarkt ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Zomerfeest ........................................................................................................................................ 9 Oproep ............................................................................................................................................ 10 Algemene informatie ......................................................................................................................... 10 Voorwoord Wandelen -

Defensie- En Oorlogsschade in Kaart Gebracht (1939-1945)

Defensie- en oorlogsschade IN KAART GEBRACHT (1939-1945) Elisabeth van Blankenstein MEI 2006/ZEIST In opdracht van het Projectteam Wederopbouw van de Rijksdienst voor de Monumentenzorg 2 Inhoudsopgave Inhoudsopgave 3 Ten geleide 5 Inleiding 7 A. Toelichting gebruikte bronnen 9 B. Voorkomende begrippen en termen 11 Deel 1 13 Algemene overzichten defensie-, oorlogsgeweld- en bezettingschade 1) Woningen 14 2) Boerderijen 18 3) Schadecijfers woningen, boerderijen, bedrijven, kerken, scholen, enzovoort 22 4) Spoorweggebouwen 24 5) Spoor- en verkeersbruggen 25 6) Vaarwegen, sluizen, stuwen en havens 29 7) Molens 31 8) Bossen 33 9) Schade door inundaties 35 10) Schade door Duitse V-wapens 41 11) Schadeoverzichten per gemeente 42 12) Stagnerende woningbouw en huisvestingsproblematiek 1940 - 1945 49 13) Industriële schade door leegroof en verwoesting 50 14) Omvang totale oorlogsschade in guldens 51 Deel 2 53 Alfabetisch overzicht van defensie-, oorlogs en bezettingsschade in provincies, regio’s, steden en dorpen in Nederland Bijlage 1 Chronologisch overzicht van luchtaanvallen op Nederland 1940-1945 219 Colofon 308 3 4 Ten geleide In 2002 werd door het Projectteam Wederopbouw van de Rijksdienst voor de Monumentenzorg (RDMZ) een eerste aanzet gegeven tot een onderzoek naar de oorlogsschade in het buitengebied. Het uiteindelijke doel was het opstellen van een kaart van Nederland met de belangrijkste wederopgebouwde en heringerichte gebieden van Nederland. Belangrijkste (eerste) bron voor het verkennend onderzoek was uiteraard Een geruisloze doorbraak. De ge- schiedenis van architectuur en stedebouw tijdens de bezetting en wederopbouw van Nederland (1995) onder redactie van Koos Bosma en Cor Wagenaar. Tijdens het verkennend onderzoek door stagiaire Suzanne de Laat bleek dat diverse archieven niet bij elkaar aansloten, met betrekking tot oorlogsschade slecht ontsloten waren, verschillende cijfers hanteerden en niet altijd eenduidig waren. -

The Semi-Enclosed Tidal Bay Eastern Scheldt in the Netherlands: Porpoise Heaven Or Porpoise Prison?

The semi-enclosed tidal bay Eastern Scheldt in the Netherlands: porpoise heaven or porpoise prison? Simone van Dam1, Liliane Solé1,2, Lonneke L. IJsseldijk3, Lineke Begeman3,4 & Mardik F. Leopold1 1 Wageningen Marine Research, Ankerpark 27, NL-1781 AG Den Helder, the Netherlands, e-mail: [email protected] 2 HZ University of Applied Sciences, Edisonweg 4, NL-4382 NW Vlissingen, the Netherlands 3 Department of Pathobiology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Utrecht University, Yalelaan 1, NL-3584 CL Utrecht, the Netherlands 4 Department of Viroscience, Erasmus MC, Wytemaweg 80, NL-3015 CN Rotterdam, the Netherlands Abstract: Harbour porpoises (Phocoena phocoena), the smallest of cetaceans, need to consume quantities of prey that amount to ca. 10% of their own body mass per day. They mostly feed on small fish, with the main prey spe- cies differing geographically. The δ¹³C muscle signature of harbour porpoises sampled in the Eastern Scheldt, SW Netherlands, has indicated that animals tend to stay here for some time after they entered this semi-enclosed basin, and that they thus must feed on local prey. A relatively low primary production and low local fish biomass raises the question what there is for harbour porpoises to feed on in the Eastern Scheldt. This study reveals that there are no big differences between biological or stranding parameters of harbour porpoises found dead in the Eastern Scheldt compared with the adjacent North Sea (the “Voordelta”), but some differences in diet were found. Still, despite the low fish biomass in the Eastern Scheldt, no evidence of excessive harbour porpoise starvation was found. -

Everything You Should Know About Zeeland Provincie Zeeland 2

Provincie Zeeland History Geography Population Government Nature and landscape Everything you should know about Zeeland Economy Zeeland Industry and services Agriculture and the countryside Fishing Recreation and tourism Connections Public transport Shipping Water Education and cultural activities Town and country planning Housing Health care Environment Provincie Everything you should know about Zeeland Provincie Zeeland 2 Contents History 3 Geography 6 Population 8 Government 10 Nature and landscape 12 Economy 14 Industry and services 16 Agriculture and the countryside 18 Fishing 20 Recreation and tourism 22 Connections 24 Public transport 26 Shipping 28 Water 30 Education and cultural activities 34 Town and country planning 37 Housing 40 Health care 42 Environment 44 Publications 47 3 History The history of man in Zeeland goes back about 150,000 brought in from potteries in the Rhine area (around present-day years. A Stone Age axe found on the beach at Cadzand in Cologne) and Lotharingen (on the border of France and Zeeuwsch-Vlaanderen is proof of this. The land there lies for Germany). the most part somewhat higher than the rest of Zeeland. Many Roman artefacts have been found in Aardenburg in A long, sandy ridge runs from east to west. Many finds have Zeeuwsch-Vlaanderen. The Romans came to the Netherlands been made on that sandy ridge. So, you see, people have about the beginning of the 1st century AD and left about a been coming to Zeeland from very, very early times. At Nieuw- hundred years later. At that time, Domburg on Walcheren was Namen, in Oost- Zeeuwsch-Vlaanderen, Stone Age arrowheads an important town. -

Toekomstbestendige Mark-Dintel-Vliet Boezem (PDF)

Toekomstbestendige Mark- Dintel-Vliet boezem ROBAMCI Fase 4 (2018-2019) Risk and Opportunity Based Asset Management for Critical Infrastructures Toekomstbestendige Mark-Dintel- Vliet boezem ROBAMCI Fase 4 (2018-2019) Wouter van der Wiel (IV-Infra) Karolina Wojciechowska (Deltares) Jasper Bink (BZIM) Klaas-Jan Douben (Waterschap Brabantse Delta) Peter Voortman (IV-Infra) Dana Stuparu (Deltares) Frank den Heijer (Deltares) © Deltares, 2019, B Titel Toekomstbestendige Mark-Dintel-Vliet boezem Opdrachtgever Project Kenmerk Pagina's Waterschap Brabantse 11201843-007 11201843-007-ZWS-0008 27 Delta, BREDA Trefwoorden ROBAMCI, Mark-Dintel-Vliet boezem, klimaatverandering, life-cycle management, baggeren, dijkversterking, RTC-model, Probabilistic Toolkit Samenvatting Deze studie is uitgevoerd binnen fase 4 van het ROBAMCI project. Dit rapport geeft beschrijving en resultaten van casus "Toekomstbestendige Mark-Dintel-Vliet boezem". In deze casus is gekeken of de ROBAMCI aanpak geschikt is voor een verkenning van de wisselwerking tussen vaarwegbeheer en het beheer van regionale keringen in de Mark-Dintel• Vliet boezem. Vier verschillende strategieën zijn beschouwd: 1 Niets doen 2 Alleen baggeren 3 Alleen dijken ophogen 4 Dijken ophogen en baggeren Uit de analyses blijkt dat over het gehele systeem bekeken strategie 3 het voordeligst is, gevolgd door strategie 4. Als echter per dijkvak beschouwd wordt welke strategie het voordeligst is, dan is een kenmerkende ruimtelijke verdeling zichtbaar. In het westen, waar de minimale dijkhoogtes het hoogst zijn vanwege de aanwezigheid van oude zeedijken, is de strategie. 'niets doen' het voordeligst. In het oosten is de voorkeursstrategie echter 'dijken ophogen en baggeren'. Deze strategie 4 is hier voordeliger dan stra_tegie3, aangezien het baggeren zorgt voor een kleinere toename in faalkans, waardoor pas op een later moment de duurdere investering van het dijkophogen nodig is.