Ross Ellis Memorial Lecture Ross Ellis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Story of the Military Museums

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2020-02 Treasuring the Tradition: The Story of the Military Museums Bercuson, David Jay; Keshen, Jeff University of Calgary Press Bercuson, D. J., & Keshen, J. (2020). Treasuring the Tradition: The story of the Military Museums. Calgary, AB: The University of Calgary Press. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/111578 book https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca TREASURING THE TRADITION: Treasuring the Tradition THE STORY OF THE MILITARY MUSEUMS The Story of the Military Museums by Jeff Keshen and David Bercuson ISBN 978-1-77385-059-7 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please Jeff Keshen and David Bercuson support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

The Militia Gunners

Canadian Military History Volume 21 Issue 1 Article 8 2015 The Militia Gunners J.L. Granatstein Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation J.L. Granatstein "The Militia Gunners." Canadian Military History 21, 1 (2015) This Feature is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. : The Militia Gunners The Militia Gunners J.L. Granatstein y general repute, two of the best in 1926 in Edmonton as a boy soldier, Bsenior artillery officers in the Abstract: Two of the best senior got his commission in 193[2], and in Canadian Army in the Second World artillery officers in the Canadian the summer of 1938 was attached Army in the Second World War were War were William Ziegler (1911-1999) products of the militia: William to the Permanent Force [PF] as an and Stanley Todd (1898-1996), both Ziegler (1911-1999) and Stanley instructor and captain. There he products of the militia. Ziegler had Todd (1898-1996). Ziegler served mastered technical gunnery and a dozen years of militia experience as the senior artillery commander in became an expert, well-positioned before the war, was a captain, and was 1st Canadian Infantry Division in Italy to rise when the war started. He from February 1944 until the end of in his third year studying engineering the war. Todd was the senior gunner went overseas in early 1940 with at the University of Alberta when in 3rd Canadian Infantry Division the 8th Field Regiment and was sent his battery was mobilized in the and the architect of the Canadian back to Canada to be brigade major first days of the war. -

Edmund Fenning Parke. Lance Corporal. No. 654, Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry

Great War in the Villages Project Edmund Fenning Parke . Lance Corporal. No. 654, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (Eastern Ontario Regiment.) Thirty miles from its source, the River Seven passes the village of Aberhafesp, near to the town of Newtown in the Montgomeryshire (Powys) countryside. It was here on the 20 June 1892 that Edmund Fenning Parke was born. His father, Edward, worked as an Architect and Surveyor and originated from Bidford-on-Avon, Warwickshire. His mother Harriette Elizabeth(nee Dolbey) was born in Newtown. The couple had ten children all born within the surrounding area of their mother’s home town. Edmund was the younger of their two sons. The family were living at The Pentre in Aberhafesp when Edmund was baptised on the 24 th July of the year of his birth. Within a few years the family moved to Brookside in Mochdre i again, only a short distance from Newtown. Edmund attended Newtown High School and indications are that after leaving there he worked as a clerk ii . He also spent some of his free time as a member of the 1/7 th Battalion, The Royal Welsh Fusiliers, a territorial unit based in the town iii . On the September 4 th 1910 however, Edmund set sail on the RMS Empress of Britain from Liverpool bound for a new life in Canada. The incoming passenger manifest records that he was entering Canada seeking work as a Bank Clerk. In the summer of 1914, many in Canada saw the German threat of war, in Europe, as inevitable. -

Canadian Infantry Combat Training During the Second World War

SHARPENING THE SABRE: CANADIAN INFANTRY COMBAT TRAINING DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR By R. DANIEL PELLERIN BBA (Honours), Wilfrid Laurier University, 2007 BA (Honours), Wilfrid Laurier University, 2008 MA, University of Waterloo, 2009 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in History University of Ottawa Ottawa, Ontario, Canada © Raymond Daniel Ryan Pellerin, Ottawa, Canada, 2016 ii ABSTRACT “Sharpening the Sabre: Canadian Infantry Combat Training during the Second World War” Author: R. Daniel Pellerin Supervisor: Serge Marc Durflinger 2016 During the Second World War, training was the Canadian Army’s longest sustained activity. Aside from isolated engagements at Hong Kong and Dieppe, the Canadians did not fight in a protracted campaign until the invasion of Sicily in July 1943. The years that Canadian infantry units spent training in the United Kingdom were formative in the history of the Canadian Army. Despite what much of the historical literature has suggested, training succeeded in making the Canadian infantry capable of succeeding in battle against German forces. Canadian infantry training showed a definite progression towards professionalism and away from a pervasive prewar mentality that the infantry was a largely unskilled arm and that training infantrymen did not require special expertise. From 1939 to 1941, Canadian infantry training suffered from problems ranging from equipment shortages to poor senior leadership. In late 1941, the Canadians were introduced to a new method of training called “battle drill,” which broke tactical manoeuvres into simple movements, encouraged initiative among junior leaders, and greatly boosted the men’s morale. -

CANDAU, Marcolino Gomes, Brazilian Physician and Second Director

1 CANDAU, Marcolino Gomes, Brazilian physician and second Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO) 1953-1973, was born 30 May 1911 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil and died 23 January 1983 in Geneva, Switzerland. He was the son of Julio Candau and Augusta Gomes Pereira. On 30 May 1936 he married Ena de Carvalho, with whom he had two sons. After their divorce he married Sîtâ Reelfs in 1973. Source: www.who.int/features/history/1940_1959/en/index7.html Candau’s family was of French-Portuguese ancestry. Candau studied at the School of Medicine of the State of Rio de Janeiro, where he earned his living by tutoring his fellow students on anatomy, and completed his medical training in 1933. Shortly after finishing his studies he decided to work in public health and demonstrated administrative skills in his first job as head of a provincial health unit in São João Marcos. A state scholarship allowed him to take a special course in public health at the University of Brazil in 1936. He also worked in the city health departments of Santana de Japuiba and Nova Iguaçu. In 1938 he was promoted to Assistant Director-General of the Department of Health of the State of Rio de Janeiro and appointed assistant professor of hygiene at the School of Medicine. In the same year Fred L. Soper, representative of the Rio de Janeiro-based Rockefeller Foundation in Brazil, asked Candau to work under his direction in a major eradication campaign against a malaria outbreak produced by the Anopheles gambiae mosquito, which resulted in Candau’s fieldwork as a medical officer in the Northeast Malaria Service. -

The Canadian Militia in the Interwar Years, 1919-39

THE POLICY OF NEGLECT: THE CANADIAN MILITIA IN THE INTERWAR YEARS, 1919-39 ___________________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board ___________________________________________________________ in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY __________________________________________________________ by Britton Wade MacDonald January, 2009 iii © Copyright 2008 by Britton W. MacDonald iv ABSTRACT The Policy of Neglect: The Canadian Militia in the Interwar Years, 1919-1939 Britton W. MacDonald Doctor of Philosophy Temple University, 2008 Dr. Gregory J. W. Urwin The Canadian Militia, since its beginning, has been underfunded and under-supported by the government, no matter which political party was in power. This trend continued throughout the interwar years of 1919 to 1939. During these years, the Militia’s members had to improvise a great deal of the time in their efforts to attain military effectiveness. This included much of their training, which they often funded with their own pay. They created their own training apparatuses, such as mock tanks, so that their preparations had a hint of realism. Officers designed interesting and unique exercises to challenge their personnel. All these actions helped create esprit de corps in the Militia, particularly the half composed of citizen soldiers, the Non- Permanent Active Militia. The regulars, the Permanent Active Militia (or Permanent Force), also relied on their own efforts to improve themselves as soldiers. They found intellectual nourishment in an excellent service journal, the Canadian Defence Quarterly, and British schools. The Militia learned to endure in these years because of all the trials its members faced. The interwar years are important for their impact on how the Canadian Army (as it was known after 1940) would fight the Second World War. -

Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry

1 PRINCESS PATRICIA’S CANADIAN LIGHT INFANTRY (Thierens Family Archives) WWAARR DDIIAARRIIEESS11991144 --11991199 Transcribed by Michael Thierens, 1914, 1915 and part of 1916 proofread and commented on by Donna Walker & Ross Toms. The complete War Diary was proofread by Stephen K. Newman, who also made valuable suggestions regarding lay-out and provided much additional information on individual soldiers and diligently researched and pin pointed the locations of the Regiment. [email protected] © Michael Thierens 2008. Introduction The P.P.C.L.I. was an unique regiment in that it was raised and financed by business man A. Hamilton Gault in August 1914 and saw action in France under British command from January 1915 onwards. It was the first Canadian regiment in the field, even though initially only 10 % of the men was Canadian born. More than 5.000 men served with the regiment in France and Flanders, 1300 never returned to Canada. In November 1915 the P.P.C.L.I., together with the Royal Canadian Regiment and the 42nd and 49th Canadian Infantry Battalions, became part of the 7th Canadian Infantry Brigade, 3rd Canadian Division. This War Diary has been transcribed in order that military and family historians and future generations can study the history of the regiment. To preserve the historical significance of these documents, typographical errors in the original documents have been maintained. 1 2 Square brackets [ ] surround information using italics added by the transcriber where it was felt that clarification was required, or where names and/or service numbers were misspelled. Question marks ? were used where the characters/words could not be discerned. -

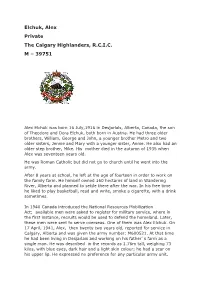

Elchuk, Alex Private the Calgary Highlanders, R.C.I.C. M – 39751

Elchuk, Alex Private The Calgary Highlanders, R.C.I.C. M – 39751 Alex Elchuk was born 16 July,1916 in Desjarlais, Alberta, Canada, the son of Theodore and Dora Elchuk, both born in Austria. He had three older brothers, William, George and John, a younger brother Metro and two older sisters, Jennie and Mary with a younger sister, Annie. He also had an older step brother, Mike. His mother died in the autumn of 1935 when Alex was seventeen years old. He was Roman Catholic but did not go to church until he went into the army. After 8 years at school, he left at the age of fourteen in order to work on the family farm. He himself owned 160 hectares of land in Wandering River, Alberta and planned to settle there after the war. In his free time he liked to play basketball, read and write, smoke a cigarette, with a drink sometimes. In 1940 Canada introduced the National Resources Mobilization Act; available men were asked to register for military service, where in the first instance, recruits would be used to defend the homeland. Later, these men were sent to serve overseas. One of them was Alex Elchuk. On 17 April, 1941, Alex, then twenty two years old, reported for service in Calgary, Alberta and was given the army number: M600521. At that time he had been living in Desjarlais and working on his father’ s farm as a single man. He was described in the records as 1.76m tall, weighing 73 kilos, with blue eyes, dark hair and a light skin colour; he had a scar on his upper lip. -

Yankees Who Fought for the Maple Leaf: a History of the American Citizens

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 12-1-1997 Yankees who fought for the maple leaf: A history of the American citizens who enlisted voluntarily and served with the Canadian Expeditionary Force before the United States of America entered the First World War, 1914-1917 T J. Harris University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Recommended Citation Harris, T J., "Yankees who fought for the maple leaf: A history of the American citizens who enlisted voluntarily and served with the Canadian Expeditionary Force before the United States of America entered the First World War, 1914-1917" (1997). Student Work. 364. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/364 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Yankees Who Fought For The Maple Leaf’ A History of the American Citizens Who Enlisted Voluntarily and Served with the Canadian Expeditionary Force Before the United States of America Entered the First World War, 1914-1917. A Thesis Presented to the Department of History and the Faculty of the Graduate College University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts University of Nebraska at Omaha by T. J. Harris December 1997 UMI Number: EP73002 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Qua~Er Thought and Life Today

Qua~er Thought and Life Today VOLUME 10 JUNE 15, 1964 NUMBER 12 @uR period h"' dedded Painter of Peaceable Kingdoms for a secular world. That was by Walter Teller a great and much-needed deci sion . .. It gave consecration and holiness to our daily life and work. Yet it excluded those deep things for which UN Experiments in Peacekeeping religion stands: the feeling for by Robert H. Cory, Jr. the inexhaustible mystery of life, the grip of an ultimate meaning of existence, and the invincible power of an uncon A Fable for Friends drtional devotion. These things cannot be excluded. If by James J. Pinney we try to expel them in their divine images, they re-emerge in demonic images. - PAUL TILLICH What About Irish Friends? by Helen F. Campbell Civil DisobediJence: A Student View THIRTY CENTS $5.00 A YEAR Letter from England 266 · FRIENDS JOURNAL June 15, 1964 Civil Disobedience-A Student View FRIENDS JOURNAL (A report by Friends' Select School seniors) N three occasions early this spring, Friends' Select School 0 in Philadelphia was presented with the gentle challenge of George Lakey, secretary of the Friends' Peace Committee. A most effective speaker, he was immediately popular, even with those who radically disapproved of his viewpoint. He attempted an explanation and defense of nonviolent civil dis obedience, both as a social tactic and as an individual ethic, illustrating his talks with such profound examples as his own Published semimonthly, on the first and fifteenth of each recent experiences in Albany, Georgia. month, at 1515 Cherry Street, Philadelphia, PennSYlvania 19102, by Friends Publishing Corporation (LO 3-7669). -

This Week in New Brunswick History

This Week in New Brunswick History In Fredericton, Lieutenant-Governor Sir Howard Douglas officially opens Kings January 1, 1829 College (University of New Brunswick), and the Old Arts building (Sir Howard Douglas Hall) – Canada’s oldest university building. The first Baptist seminary in New Brunswick is opened on York Street in January 1, 1836 Fredericton, with the Rev. Frederick W. Miles appointed Principal. Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) becomes responsible for all lines formerly January 1, 1912 operated by the Dominion Atlantic Railway (DAR) - according to a 999 year lease arrangement. January 1, 1952 The town of Dieppe is incorporated. January 1, 1958 The city of Campbellton and town of Shippagan become incorporated January 1, 1966 The city of Bathurst and town of Tracadie become incorporated. Louis B. Mayer, one of the founders of MGM Studios (Hollywood, California), January 2, 1904 leaves his family home in Saint John, destined for Boston (Massachusetts). New Brunswick is officially divided into eight counties of Saint John, Westmorland, Charlotte, Northumberland, King’s, Queen’s, York and Sunbury. January 3, 1786 Within each county a Shire Town is designated, and civil parishes are also established. The first meeting of the New Brunswick Legislature is held at the Mallard House January 3, 1786 on King Street in Saint John. The historic opening marks the official business of developing the new province of New Brunswick. Lévite Thériault is elected to the House of Assembly representing Victoria January 3, 1868 County. In 1871 he is appointed a Minister without Portfolio in the administration of the Honourable George L. Hatheway. -

Cholera in Egypt and the Origins of WHO, 1947

CholeraCholera inin EgyptEgypt andand thethe OriginsOrigins ofof WHO,WHO, 19471947 Marcos Cueto Professor Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia Part of a larger study on the history of WHO, Global Health Histories initiative, E. Fee, T. Brown et al. GeneralGeneral themetheme andand questions:questions: In 1947 the organizers of WHO planned to hold the 1st World Health Assembly within a few months but the process took longer and faced urgent problems such as a cholera outbreak Tension between the need to respond to emergencies and institution building processes How to combine relief with prevention? How to modernize quarantine regulations? How to work in a conflictive region and period? (Palestine refugees, the creation of Israel, the beginning of the Cold War) John Lennon “Life is what happens to you while you are busy making other plans” BackgroundBackground Between 1882-1920s part of the British Empire but never officially a colony In 1922 the UK unilaterally declared independence However, British influence continued (maintaining its control over the Suez canal) Occupied by the Germans during most of the WWII In the early 20th century an export economy: cotton In 1947 the total population of the country over 19 million British soldiers at the piramid of Giza, c. 1899 www.artehistoria.com H.M. Farouk I, King of Egypt and of Sudan. ruled Egypt between 1936 and 1952. Undermined by accusations of a lavish royal lifestyle in a poor country, corruption and pick-pocketing In 1945 Egypt became a member of the Arab League with headquarters in Cairo; against UN plan for partition of Palestine into an Arab and a Jewish state Egypt was defeated during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War but maintained control of a strip of territory around Gaza A country on the threshold of a revolution A military coup in 1952, directed by Gamal A.