Department of History Al Neelain University Khartoum, Sudan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: the Role of Traditional Institutions

Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria Past, Present, and Future Edited by Abdalla Uba Adamu ii Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria Past, Present, and Future Proceedings of the National Conference on Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria. Organized by the Kano State Emirate Council to commemorate the 40th anniversary of His Royal Highness, the Emir of Kano, Alhaji Ado Bayero, CFR, LLD, as the Emir of Kano (October 1963-October 2003) H.R.H. Alhaji (Dr.) Ado Bayero, CFR, LLD 40th Anniversary (1383-1424 A.H., 1963-2003) Allah Ya Kara Jan Zamanin Sarki, Amin. iii Copyright Pages © ISBN © All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the editors. iv Contents A Brief Biography of the Emir of Kano..............................................................vi Editorial Note........................................................................................................i Preface...................................................................................................................i Opening Lead Papers Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: The Role of Traditional Institutions...........1 Lt. General Aliyu Mohammed (rtd), GCON Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: A Case Study of Sarkin Kano Alhaji Ado Bayero and the Kano Emirate Council...............................................................14 Dr. Ibrahim Tahir, M.A. (Cantab) PhD (Cantab) -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

A Public Consultative Forum for Northern Sanetorial

A PUBLIC CONSULTATIVE FORUM FOR NORTHERN SANETORIAL ZONE ON THE TARABA STATE 2021 BUDGET PROCESS HELD ON THE 26TH SEPTEMBER, 2020 AT THE COUNCIL CHAMBERS ZING LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA BY 9:00AM. IN ATTENDANCE: 1. KPANTI ZING REP. 2. CHAIRMAN ZING LOCAL GOVERNMENT 3. 1 VILLAGE HEADS 4. CDOS OF ARDO KOLA, JALINGO, LAU, KARIM LAMIDO, YORRO AND ZING. 5. CSOs REPS. FROM JALINGO AND ZING 6. YOUTH LEADERS FROM ARDO KOLA, JALINGO. LAU, KARIM LAMIDO, YORRO AND ZING 7. WOMEN GROUP 8. RELIGIOUS BODIES 9. FARMERS 10. HERDERS 11. MARKET WOMEN 12. PEOPLE LIVING WITH DISABILITIES 13. TRADERS 14. DIRECTOR OF BUDGET OF ARDO KOLA, JALINGO, LAU, KARIM LAMIDO, YORRO AND ZING AGENDA: See attached INTRODUCTIONS After opening prayers (which was the second stanza) of the National Anthem, speeches and self- introductions were taken by 9:47am. I was introduced to explain why the zonal consultation with various stakeholders in the Northern Senatorial Zone. That citizens participation in the state budget process is very importance in the development of the state. It creates a partnership and agreement between the people and their elected representatives to give more and do more to the people. The involvement of the citizens in the budget process is to ensured accountability, transparency and create demands for citizens needs. Citizens participations in the budget process empowered them to determine the kind of projects they need and where to locate them. Their engagement in this process give the citizens powers of development in their hands. Since budgeting allows you to create a spending plan for your money, it ensures that you will always have enough money for the things you need and the things that are important to you. -

Distribution and Prevalence of Human Onchocerciasis in Ardo-Kola and Yorro Local Government Areas, Taraba State, Nigeria

Adamawa State University Journal of Scientific Research ISSN: 2251-0702 (P) Volume 6 Number 2, August, 2018; Article no. ADSUJSR 0602018 http://www.adsujsr.com Distribution and Prevalence of Human Onchocerciasis in Ardo-Kola and Yorro Local Government Areas, Taraba State, Nigeria 1* 2 1 2 1 3 Danladi, T ., Elkanah, S. O ., Wahedi, J. A ., Elkanah, D. S ., Elihu, A ., Akafyi, D.E . 1Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, Adamawa State University (ADSU), P.M.B. 25, Mubi, Adamawa State, Nigeria. 2Parasitology and Public Health Unit, Department of Biological Sciences, Taraba State University, P.M.B. 1167, Jalingo, Taraba State. 3Nigeria Institute of Leather and Science Technology Zaria, Kaduna State. Contact: [email protected] Phone: +2348037725303 Abstract Onchocerciasis is a chronic parasitic disease caused by the filarial nematode; Onchocerca volvulus and is transmitted by different species of blackflies. A study was carried out to assess the prevalence and distribution of human Onchocerciasis in Gonta, Shompa, Voding, Kasakuru and Kwanti-Nyavo communities of Ardo-kola and Yorro Local Government areas of Taraba State, Nigeria. Standard parasitological techniques of skin snip were used to collect data. A total of five hundred persons were examined comprising of 275(55.0%) males and 225(45.0%) females. Of these, 187(37.4%) were infected with Onchocerca volvulus. The male subjects are more infected (45.5%) than their female counterparts (27.5%) with statistically Significant difference in infection (2= 16.934, P = 0.000). Age-specific prevalence of infection was recorded in all age groups displaying a progressive increase with increase in age. Age group 41-50 shows the highest prevalence of infection 32(45.1%), Chi square analysis shows no significant difference in infection among age groups (2= 3.440, P= 0.633). -

Ningi Raids and Slavery in Nineteenth Century Sokoto Caliphate

SLAVERY AND ABOLITION A Journal of Comparative Studies Edilorial Advisory Boord · RogerT. Anstey (Kent) Ralph A. Austen (Chicago) Claude Meillassoux (Paris) David Brion Davis (Yale) Domiltique de Menil (Menil ~O'LIlmllllllll Carl N. Degler (Stanford) Suzanne Miers (Ohio) M.1. Finley (Cambridge) Joseph C. Miller (Virginia) Jan Hogendorn (Colby) Orlando Patterson (Harvard) A. G. Hopkins (Birmingham) Edwin Wolf 2nd (Library Co. of Winthrop D. Jordan (Berkeley) Philadelphia) Ion Kenneth Maxwell (Columbia) Edit"': Associate Ediwr: John Ralph Willis (Princeton) C. Duncan Rice (Hamilton) Volume 2 Number 2 September 1981 .( deceased) Manusc ripts and all editorial correspondence and books for review should be Tuareg Slavery and the Slave Trade Priscill a Elle n Starrett 83 (0 Professor John Ralph Willis, Near Eastern Studies Department, Prince. University , Princeton, New Jersey 08540. ~in gi Raids and Slave ry in Nineteenth Articles submiued [0 Slavery and Abolilion are considered 0t:\ the understanding Centu ry Sokoto Ca liphate Adell Patton, Jr. 114 they are not being offered for publication elsewhere , without the exp ressed cO losenll the Editor. Slavery: Annual Bibliographical Advertisement and SUbscription enquiries should be sent to Slavery and IIbol"'", Supplement (198 1) Joseph C. Miller 146 Frank Cass & Co. Ltd., Gainsborough House, II Gainsborough London Ell IRS. The Medallion on the COVel" is reproduced by kind perm.ission of Josiah W"dgwoocU Sons Ltd. © Frank Cass & Co. Ltd. 1981 All rigllt! ,eseroed. No parr of his publication may be reprodU4ed. siored in 0 retrieval sysu.. lJ'anmliJt~d in anyfarm. or by any ,"eal'lJ. eUclJ'onic. rMchonicoJ. phalocopying. recording. or without tlu pn·or permissicm of Frank Call & Co. -

Jesus, the Sw, and Christian-Muslim Relations in Nigeria

Conflicting Christologies in a Context of Conflicts: Jesus, the sw, and Christian-Muslim Relations in Nigeria Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doctor rerum religionum (Dr. rer. rel.) der Theologischen Fakultät der Universität Rostock vorgelegt von Nguvugher, Chentu Dauda, geb. am 10.10.1970 in Gwakshesh, Mangun (Nigeria) aus Mangun Rostock, 21.04.2010 Supervisor Prof. Dr. Klaus Hock Chair: History of Religions-Religion and Society Faculty of Theology, University of Rostock, Germany Examiners Dr. Sigvard von Sicard Honorary Senior Research Fellow Department of Theology and Religion University of Birmingham, UK Prof. Dr. Frieder Ludwig Seminarleiter Missionsseminar Hermannsburg/ University of Goettingen, Germany Date of Examination (Viva) 21.04.2010 urn:nbn:de:gbv:28-diss2010-0082-2 Selbständigkeitserklärung Ich erkläre, dass ich die eingereichte Dissertation selbständig und ohne fremde Hilfe verfasst, andere als die von mir angegebenen Quellen und Hilfsmittel nicht benutzt und die den benutzten Werken wörtlich oder inhaltlich entnommenen Stellen als solche kenntlich gemacht habe. Statement of Primary Authorship I hereby declare that I have written the submitted thesis independently and without help from others, that I have not used other sources and resources than those indicated by me, and that I have properly marked those passages which were taken either literally or in regard to content from the sources used. ii CURRICULUM VITAE CHENTU DAUDA NGUVUGHER Married, four children 10.10.1970 Born in Gwakshesh, Mangun, Plateau -

The Environmental Issues of Taraba State Bako T

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 7, Issue 2, February-2016 286 ISSN 2229-5518 The Environmental Issues of Taraba State Bako T. 1, Oparaku L.A. 2 and Flayin J.M. 3 Abstract-The objective of this paper is to discuss the nature of environmental degradation (limitation) as a result of desertification, deforestation, flooding, soil erosion and climate change, in terms of their impact on productivity and to suggest potential strategies for amelioration or management strategies to prevent degradation and to maintain an environmental balance for sustainable security. This study was conducted to examine some of the environmental problems of Taraba State. Data were generated from secondary sources as well as photographs. The paper highlights some environmental problems of Taraba State. The paper recommends ecosystem education, natural resource rehabilitation, improved technology, environmental data bank, population data and enablement of existing environmental policies among other measures to overcome the environmental problems. It also advocates for the integration of both local and advanced environmental management strategies in order to achieve a sustainable environment. Keywords: Environment, Issues, sustainability, Taraba State. 1 INTRODUCTION on which humans and other species depend, provide basic human needs in terms of food, in Environment is a resource, which is being economically viable manner and enhances the consumed at an exponential rate. Unfortunately, quality of life for the society as a whole. this resource cannot be easily replenished. This has led to a lot of environmental concerns and issues 1.2 Location and Physical Setting of which need to be dealt with on a war footing. The Taraba State global scenario today is fraught with drought, Location: Taraba State lies roughly between famine, floods, and other natural calamities. -

An Assessment of Sakkwato Jihad Flag Bearers of Katagum, Misau and Jama’Are Local Government of Bauchi State and Their Contributions to Islamic Education

AN ASSESSMENT OF SAKKWATO JIHAD FLAG BEARERS OF KATAGUM, MISAU AND JAMA’ARE LOCAL GOVERNMENT OF BAUCHI STATE AND THEIR CONTRIBUTIONS TO ISLAMIC EDUCATION BY SHEHU SABO M.ED/EDUC/42665,04-05 DEPARTMENT OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCE EDUCATION ISLAMIC STUDIES SECTION FACULTY OF EDUCATION AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA. AUGUST, 2011 AN ASSESSMENT OF SAKKWATO JIHAD FLAG BEARERS OF KATAGUM, MISAU AND JAMA’ARE LOCAL GOVERNMENT OF BAUCHI STATE AND THEIR CONTRIBUTIONS TO ISLAMIC EDUCATION BY SHEHU SABO M.ED/EDUC/42665,04-05 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL, AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY ZARIA IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF EDUCATION DEGREE IN ISLAMAIC STUDIES. DEPARTMENT OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCE EDUCATION ISLAMIC STUDIES SECTION FACULTY OF EDUCATION AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA. AUGUST, 2011 DECLARATION I hereby declare that his research (thesis) has been carried out by me. The topic has not been touched by any researcher previously. All the information obtained and indicated in the research and the sources of information are duly acknowledged. ______________________ Shehu Sabo M.ED/EDUC/42665/04-05 DEDICATION I wish to dedicate this research to my parents and the entire people of Katagum, Misau and Jama’are emirates. CERTIFICATION This research work has been read and approved as meeting the requirements for the award of Master of Education (Islamic Studies) of Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria. __________________________ ___________________ Dr. Abdukadir Aliyu Ladan Date Chairman Supervisory Committee __________________________ ___________________ Dr. Abdullahi Dalhat Date Member Supervisory Committee __________________________ ___________________ Dr. Abdukadir Aliyu Ladan Date Head of Department __________________________ ___________________ Professor Adebayo A. -

AMERICAN UNIVERSITY LIBRARY N In

THE PROLIFERATION OF SMALL ARMS AND LIGHT WEAPONS IN INTERNAL CONFLICT: THE CHALLENGE OF HUMAN SECURITY IN NIGERIA By Jennifer Douglas Abubakar Submitted to the Faculty of the School of International Service of American University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In International Relations Chair: Randolph Persaud, Ph.D Peter Lewis, Ph.D atriek Jackson, Ph.D AJ,'A (a J Dean of the School of International Service T f f ) ^ '2tr?7 Date / 2007 American University Washington, D.C. 20016 AMERICAN UNIVERSITY LIBRARY n in Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3269571 Copyright 2007 by Douglas Abubakar, Jennifer All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UMI Microform 3269571 Copyright 2007 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. © COPYRIGHT by Jennifer Douglas Abubakar 2007 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

In Northern Nigeria Conference Proceedings

IN NORTHERN NIGERIA CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS Two-Day Summit on Youth Restiveness, Violence, Peace & Development in Northern Nigeria undertaken with the financial support of the Government of Canada provided through the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) THE CHALLENGES OF YOUTH RESTIVENESS, VIOLENCE AND PEACE IN NORTHERN NIGERIA CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS Two-Day Summit on Youth Restiveness, Violence, Peace & Development in Northern Nigeria undertaken with the financial support of the Government of Canada provided through the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) THE CHALLENGES OF YOUTH RESTIVENESS, VIOLENCE AND PEACE IN NORTHERN NIGERIA CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS Two-Day Summit on Youth Restiveness, Violence, Peace & Development in Northern Nigeria undertaken with the financial support of the Government of Canada provided through the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) First published in 2011 By CLEEN Foundation Lagos Office: 21 Akinsanya Street Taiwo Bus stop Ojodu, Ikeja Lagos, Nigeria Tel: +234-1-7612479 Fax: +234-1-2303230 The mission of CLEEN Foundation is to promote Abuja Office: public safety, security and accessible justice through 26 Bamenda Street empirical research, legislative advocacy, Off Abidjan Street Wuse Zone 3 demonstration programmes and publications in Abuja, Nigeria partnership with government and civil society. Tel: +234-9-7817025 +234-9-8708379 Owerri Office: Plot 10, Area M Road 3, World Bank Housing Estate Owerri, Imo State, Nigeria Tel: +234-083-823104 Email: [email protected] Website: www.cleen.org ISBN: 978-978-53083-9-6 © All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, photocopying, mechanical, recording or otherwise, without the prior approval of the CLEEN Foundation. -

"I,Gie'colflietassessm

Federal Government of Nigeria . '. ;" I,gie 'Colfliet Assessm Consolidated and Zonal Reports Nigefa nstitute lor Peace and Co f iel 8S0 ulion The Pres·de cy Abuja March 2003 FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA STRATEGIC CONFLICT ASSESSMENT (SCA) REPORT MARCH 2002 BY INSTITUTE FOR PEACE AND CONFLICT RESOLUTION THE PRESIDENCY ii Publisher: INSTITUTE FOR PEACE AND CONFLICT RESOLUTION (IPCR) Head Office: The presidency Plot 496 Abogo Largema Street Off Constitution Avenue, Central Business District Abuja Telephone: 234-9-523-9458 © IPCR ISBN 978-36814-1-9 First Published 2003 Production by: lFA1et VEditions All Rights Reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced. stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior pemzission ofInstitute for Peace and Conflict Resolution ( [peR). This book is sold subject to the condition that it should not by any way of trade or otherwise be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form oj binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. Printed by: The Regent (Printing and Publishing) Ltd. No.1 Dabson LinklArgungu Road, OJ! Katsina Road P. O. Box 1380, Kaduna iii FOREWORD he Institute acknowledges with gratitude and respect the attention .. given by the President to the issue of conflict. He has recognised T..and asked others to face up to "the deep and persistent concern about the threat which violence poses to our electoral process and indeed to the survival of the democratic system in general and to our unity and oneness"~ . -

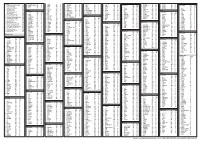

States and Lcdas Codes.Cdr

PFA CODES 28 UKANEFUN KPK AK 6 CHIBOK CBK BO 8 ETSAKO-EAST AGD ED 20 ONUIMO KWE IM 32 RIMIN-GADO RMG KN KWARA 9 IJEBU-NORTH JGB OG 30 OYO-EAST YYY OY YOBE 1 Stanbic IBTC Pension Managers Limited 0021 29 URU OFFONG ORUKO UFG AK 7 DAMBOA DAM BO 9 ETSAKO-WEST AUC ED 21 ORLU RLU IM 33 ROGO RGG KN S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 10 IJEBU-NORTH-EAST JNE OG 31 SAKI-EAST GMD OY S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 2 Premium Pension Limited 0022 30 URUAN DUU AK 8 DIKWA DKW BO 10 IGUEBEN GUE ED 22 ORSU AWT IM 34 SHANONO SNN KN CODE CODE 11 IJEBU-ODE JBD OG 32 SAKI-WEST SHK OY CODE CODE 3 Leadway Pensure PFA Limited 0023 31 UYO UYY AK 9 GUBIO GUB BO 11 IKPOBA-OKHA DGE ED 23 ORU-EAST MMA IM 35 SUMAILA SML KN 1 ASA AFN KW 12 IKENNE KNN OG 33 SURULERE RSD OY 1 BADE GSH YB 4 Sigma Pensions Limited 0024 10 GUZAMALA GZM BO 12 OREDO BEN ED 24 ORU-WEST NGB IM 36 TAKAI TAK KN 2 BARUTEN KSB KW 13 IMEKO-AFON MEK OG 2 BOSARI DPH YB 5 Pensions Alliance Limited 0025 ANAMBRA 11 GWOZA GZA BO 13 ORHIONMWON ABD ED 25 OWERRI-MUNICIPAL WER IM 37 TARAUNI TRN KN 3 EDU LAF KW 14 IPOKIA PKA OG PLATEAU 3 DAMATURU DTR YB 6 ARM Pension Managers Limited 0026 S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 12 HAWUL HWL BO 14 OVIA-NORTH-EAST AKA ED 26 26 OWERRI-NORTH RRT IM 38 TOFA TEA KN 4 EKITI ARP KW 15 OBAFEMI OWODE WDE OG S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 4 FIKA FKA YB 7 Trustfund Pensions Plc 0028 CODE CODE 13 JERE JRE BO 15 OVIA-SOUTH-WEST GBZ ED 27 27 OWERRI-WEST UMG IM 39 TSANYAWA TYW KN 5 IFELODUN SHA KW 16 ODEDAH DED OG CODE CODE 5 FUNE FUN YB 8 First Guarantee Pension Limited 0029 1 AGUATA AGU AN 14 KAGA KGG BO 16 OWAN-EAST