Southern Indian Studies, Vol. 31

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The People of the Falling Star

Patricia Lerch. Waccamaw Legacy: Contemporary Indians Fight for Survival. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2004. xvi + 168 pp. $57.50, cloth, ISBN 978-0-8173-1417-0. Reviewed by Thomas E. Ross Published on H-AmIndian (March, 2007) Patricia Lerch has devoted more than two presents rational assumptions about the Wacca‐ decades to the study of the Waccamaw Siouan, a maw tribe's links to colonial Indians of southeast‐ non-federally recognized Indian tribe (the tribe is ern North Carolina and the Cape Fear River recognized by the State of North Carolina) living drainage basin. in southeastern North Carolina. Her book is the She has no reservations about accepting the first volume devoted to the Waccamaw. It con‐ notion that Indians living in the region were re‐ tains nine chapters and includes sixteen photo‐ ferred to as Waccamaw, Cape Fear Indians, and graphs, fourteen of which portray the Waccamaw Woccon. Whatever the name of Indians living in during the period from 1949 to the present. The the Cape Fear region during the colonial period, first four chapters provide background material they had to react to the European advance. In on several different Indian groups in southeast‐ some instances, the Indians responded to violence ern North Carolina and northeastern South Car‐ with violence, and to diplomacy and trade with olina, and are not specific to the Waccamaw Indi‐ peace treaties; they even took an active role in the ans. Nevertheless, they are important in setting Indian Wars and the enslavement of Africans. The the stage for the chapters that follow and for pro‐ records, however, do no detail what eventually viding a broad, historical overview of the Wacca‐ happened to the Indians of the Cape Fear. -

Native Americans in the Cape Fear, by Dr. Jan Davidson

Native Americans in the Cape Fear, By Dr. Jan Davidson Archaeologists believe that Native Americans have lived in what is now the state of North Carolina for more than 13,000 years. These first inhabitants, now called Paleo-Indians by experts, were likely descended from people who came over a then-existing land bridge from Asia.1 Evidence had been found at Town Creek Mound that suggests Indians lived there as early as 11000 B.C.E. Work at another major North Carolinian Paleo-Indian where Indian artifacts have been found in layers of the soil, puts Native Americans on that land before 8000 B.C.E. That site, in North Carolina’s Uwharrie Mountains, near Badin, became an important source of stone that Paleo and Archaic period Indians made into tools such as spears.2 It is harder to know when the first people arrived in the lower Cape Fear. The coastal archaeological record is not as rich as it is in some other regions. In the Paleo-Indian period around 12000 B.C.E., the coast was about 60 miles further out to sea than it is today. So land where Indians might have lived is buried under water. Furthermore, the coastal Cape Fear region’s sandy soils don’t provide a lot of stone for making tools, and stone implements are one of the major ways that archeologists have to trace and track where and when Indians lived before 2000 B.C.E.3 These challenges may help explain why no one has yet found any definitive evidence that Indians were in New Hanover County before 8000 B.C.E.4 We may never know if there were indigenous people here before the Archaic period began in approximately 8000 B.C.E. -

Waccamaw River Blue Trail

ABOUT THE WACCAMAW RIVER BLUE TRAIL The Waccamaw River Blue Trail extends the entire length of the river in North and South Carolina. Beginning near Lake Waccamaw, a permanently inundated Carolina Bay, the river meanders through the Waccamaw River Heritage Preserve, City of Conway, and Waccamaw National Wildlife Refuge before merging with the Intracoastal Waterway where it passes historic rice fields, Brookgreen Gardens, Sandy Island, and ends at Winyah Bay near Georgetown. Over 140 miles of river invite the paddler to explore its unique natural, historical and cultural features. Its black waters, cypress swamps and tidal marshes are home to many rare species of plants and animals. The river is also steeped in history with Native American settlements, Civil War sites, rice and indigo plantations, which highlight the Gullah-Geechee culture, as well as many historic homes, churches, shops, and remnants of industries that were once served by steamships. To protect this important natural resource, American Rivers, Waccamaw RIVERKEEPER®, and many local partners worked together to establish the Waccamaw River Blue Trail, providing greater access to the river and its recreation opportunities. A Blue Trail is a river adopted by a local community that is dedicated to improving family-friendly recreation such as fishing, boating, and wildlife watching and to conserving riverside land and water resources. Just as hiking trails are designed to help people explore the land, Blue Trails help people discover their rivers. They help communities improve recreation and tourism, benefit local businesses and the economy, and protect river health for the benefit of people, wildlife, and future generations. -

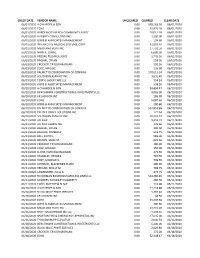

Check Date Vendor Name Uncleared Cleared Clear

CHECK DATE VENDOR NAME UNCLEARED CLEARED CLEAR DATE 06/01/2020 A O HARDEE & SON 0.00 939,163.50 06/01/2020 06/01/2020 ECHO 0.00 33,425.26 06/01/2020 06/01/2020 GARDEN CITY BEACH COMMUNITY ASSOC 0.00 10,012.74 06/01/2020 06/01/2020 HAGERTY CONSULTING INC 0.00 3,200.00 06/01/2020 06/01/2020 GORE & ASSOCIATES MANAGEMENT 0.00 124.80 06/01/2020 06/01/2020 INTERACTIVE MEDICAL SYSTEMS, CORP 0.00 32,803.67 06/01/2020 06/01/2020 MEAD AND HUNT INC 0.00 17,731.58 06/01/2020 06/01/2020 NAPIER, JOHN L 0.00 6,600.00 06/01/2020 06/01/2020 REDSAIL TECHNOLOGIES 0.00 2,745.50 06/01/2020 06/03/2020 BAGNAL, DYLAN 0.00 258.50 06/03/2020 06/03/2020 CROCKER, TAYLOR MORGAN 0.00 292.50 06/03/2020 06/03/2020 EDGE, MAGGIE 0.00 235.00 06/03/2020 06/03/2020 PALMETTO CORPORATION OF CONWAY 0.00 170,612.34 06/03/2020 06/03/2020 SOUTHERN ASPHALT INC 0.00 3,631.40 06/03/2020 06/03/2020 TERRYS LASER CARE LLC 0.00 354.24 06/03/2020 06/04/2020 GORE & ASSOCIATES MANAGEMENT 0.00 538.56 06/04/2020 06/10/2020 A O HARDEE & SON 0.00 94,894.47 06/10/2020 06/10/2020 BENCHMARK CONSTRUCTION & INVESTMENTS LLC 0.00 4,965.00 06/10/2020 06/10/2020 CR JACKSON INC 0.00 185.09 06/10/2020 06/10/2020 ECHO 0.00 5,087.66 06/10/2020 06/10/2020 GORE & ASSOCIATES MANAGEMENT 0.00 280.80 06/10/2020 06/10/2020 PALMETTO CORPORATION OF CONWAY 0.00 593,853.86 06/10/2020 06/10/2020 PEE DEE OFFICE SOLUTIONS INC 0.00 171.54 06/10/2020 06/10/2020 SOUTHERN ASPHALT INC 0.00 20,351.57 06/10/2020 06/11/2020 ASI FLEX 0.00 9,252.72 06/11/2020 06/11/2020 ASI FLEX ADMIN FEE 0.00 176.66 06/11/2020 06/11/2020 BAGNAL, DYLAN 0.00 280.50 06/11/2020 06/11/2020 BASHOR, KIMBERLY 0.00 618.75 06/11/2020 06/11/2020 BELL, JOYCE L 0.00 583.00 06/11/2020 06/11/2020 BROWN, SADIE M. -

8 Tribes, 1 State: Native Americans in North Carolina

8 Tribes, 1 State: North Carolina’s Native Peoples As of 2014, North Carolina has 8 state and federally recognized Native American tribes. In this lesson, students will study various Native American tribes through a variety of activities, from a PowerPoint led discussion, to a study of Native American art. The lesson culminates with students putting on a Native American Art Show about the 8 recognized tribes. Grade 8 Materials “8 Tribes, 1 State: Native Americans in North Carolina” PowerPoint, available here: o http://civics.sites.unc.edu/files/2014/06/NCNativeAmericans1.pdf o To view this PDF as a projectable presentation, save the file, click “View” in the top menu bar of the file, and select “Full Screen Mode”; upon completion of presentation, hit ESC on your keyboard to exit the file o To request an editable PPT version of this presentation, send a request to [email protected] “Native American Art Handouts #1 – 7”, attached North Carolina Native American Tribe handouts, attached o Lumbee o Eastern Band of Cherokee o Coharie o Haliwa-‑ Saponi o Meherrin o Occaneechi Band of the Saponi Nation o Sappony o Waccamaw Siouan “Create a Native American Art Exhibition” handout, attached “Native Americans in North Carolina Fact Sheet”, attached Brown paper or brown shopping bags (for the culminating project) Graph paper (for the culminating project) Art supplies (markers, colored pencils, crayons, etc. Essential Questions: What was life like for Native Americans before the arrival of Europeans? What happened to most Native American tribes after European arrival? What hardships have Native Americans faced throughout their history? How many state and federally recognized tribes are in North Carolina today? Duration 90 – 120 minutes Teacher Preparation A note about terminology: For this lesson, the descriptions Native American and American Indian are 1 used interchangeably when referring to more than one specific tribe. -

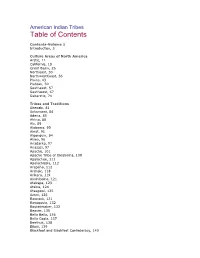

Table of Contents

American Indian Tribes Table of Contents Contents-Volume 1 Introduction, 3 Culture Areas of North America Arctic, 11 California, 19 Great Basin, 26 Northeast, 30 NorthwestCoast, 36 Plains, 43 Plateau, 50 Southeast, 57 Southwest, 67 Subarctic, 74 Tribes and Traditions Abenaki, 81 Achumawi, 84 Adena, 85 Ahtna, 88 Ais, 89 Alabama, 90 Aleut, 91 Algonquin, 94 Alsea, 96 Anadarko, 97 Anasazi, 97 Apache, 101 Apache Tribe of Oklahoma, 108 Apalachee, 111 Apalachicola, 112 Arapaho, 112 Archaic, 118 Arikara, 119 Assiniboine, 121 Atakapa, 123 Atsina, 124 Atsugewi, 125 Aztec, 126 Bannock, 131 Bayogoula, 132 Basketmaker, 132 Beaver, 135 Bella Bella, 136 Bella Coola, 137 Beothuk, 138 Biloxi, 139 Blackfoot and Blackfeet Confederacy, 140 Caddo tribal group, 146 Cahuilla, 153 Calusa, 155 CapeFear, 156 Carib, 156 Carrier, 158 Catawba, 159 Cayuga, 160 Cayuse, 161 Chasta Costa, 163 Chehalis, 164 Chemakum, 165 Cheraw, 165 Cherokee, 166 Cheyenne, 175 Chiaha, 180 Chichimec, 181 Chickasaw, 182 Chilcotin, 185 Chinook, 186 Chipewyan, 187 Chitimacha, 188 Choctaw, 190 Chumash, 193 Clallam, 194 Clatskanie, 195 Clovis, 195 CoastYuki, 196 Cocopa, 197 Coeurd'Alene, 198 Columbia, 200 Colville, 201 Comanche, 201 Comox, 206 Coos, 206 Copalis, 208 Costanoan, 208 Coushatta, 209 Cowichan, 210 Cowlitz, 211 Cree, 212 Creek, 216 Crow, 222 Cupeño, 230 Desert culture, 230 Diegueño, 231 Dogrib, 233 Dorset, 234 Duwamish, 235 Erie, 236 Esselen, 236 Fernandeño, 238 Flathead, 239 Folsom, 242 Fox, 243 Fremont, 251 Gabrielino, 252 Gitksan, 253 Gosiute, 254 Guale, 255 Haisla, 256 Han, 256 -

H.B. 765 GENERAL ASSEMBLY of NORTH CAROLINA May 3, 2021 SESSION 2021 HOUSE PRINCIPAL CLERK H D HOUSE BILL DRH10300-Lga-116

H.B. 765 GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF NORTH CAROLINA May 3, 2021 SESSION 2021 HOUSE PRINCIPAL CLERK H D HOUSE BILL DRH10300-LGa-116 Short Title: American Indian Heritage Commission. (Public) Sponsors: Representative Graham. Referred to: 1 A BILL TO BE ENTITLED 2 AN ACT TO ESTABLISH THE AMERICAN INDIAN HERITAGE COMMISSION AND TO 3 APPROPRIATE FUNDS FOR THE OPERATION OF THE COMMISSION. 4 The General Assembly of North Carolina enacts: 5 SECTION 1. Article 2 of Chapter 143B of the General Statutes is amended by adding 6 a new Part to read: 7 "Part 30A. American Indian Heritage Commission. 8 "§ 143B-135.5. American Indian Heritage Commission established. 9 (a) Creation and Duties. – There is created the American Indian Heritage Commission in 10 the Department of Natural and Cultural Resources. The Commission shall advise and assist the 11 Secretary of Natural and Cultural Resources in the preservation, interpretation, and promotion of 12 American Indian history, arts, customs, and culture. The Commission shall have the following 13 powers and duties: 14 (1) Assist in the coordination of American Indian cultural events. 15 (2) Provide oversight and management of all State-managed American Indian 16 historic sites. 17 (3) Promote public awareness of the annual American Indian Heritage Month 18 Celebration. 19 (4) Encourage American Indian cultural tourism throughout the State of North 20 Carolina. 21 (5) Advise the Secretary of Natural and Cultural Resources upon any matter the 22 Secretary may refer to it. 23 (b) Members. – The Commission shall consist of 12 members. The initial board shall be 24 selected on or before October 1, 2021, as follows: 25 (1) One representative recommended by each of the following tribes: Coharie, 26 Eastern Band of Cherokee Nation, Haliwa-Saponi, Lumbee, Meherrin, 27 Occaneechi Band of the Saponi Nation, Sappony, and Waccamaw-Siouan. -

Waccamaw River North Carolina

WACCAMAW RIVER NORTH CAROLINA Project Name: Waccamaw River Water Trail Project Type: Recreation (National Water Trail) Education Project Description: The Waccamaw River and its corridor contain critical floodplain and an important wildlife migration corridor, while also supporting many recreational opportunities and several new adventure tourism businesses. The Waccamaw River Water Trail, stretching across North and South Carolina, would be a two-state water trail from its source at Lake Waccamaw in North Carolina to Winyah Bay in South Carolina. The 60,000-acre Waccamaw River floodplain, in southeastern North Carolina, stretches south to the Waccamaw National Wildlife Refuge in South Carolina, as one of the largest contiguous wildlife habitats in the southern coastal plain. Significant features include three endemic natural communities, an endemic plant species, and 11 endemic animal species, including the federally-listed Waccamaw silverside, Waccamaw darter, and Waccamaw killifish. American Rivers Lead Federal Agency: National Park Service Non-Federal Partners: American Rivers NC State Trails Program Winyah Rivers Foundation NC Coastal Land Trust Brunswick County The Nature Conservancy Columbus County North Carolina Natural Heritage Cape Fear Council of Governments Program Cape Fear Arch Conservation North Carolina Wildlife Collaboration Resources Commission North Carolina State Parks Outcomes for 2012: Obtain National Water Trail designation Identify river access points along the 48 miles of river corridor in North Carolina Complete water trail event (media and key stakeholders kayak outing) Identify a key river access point for beginning the Water Trail Begin collecting base data for producing trail guide . -

American Indian Tribes in North Carolina

Published on NCpedia (https://www.ncpedia.org) Home > American Indian Tribes in North Carolina American Indian Tribes in North Carolina [1] Share it now! Average: 3.5 (393 votes) Map of N.C. Tribal and Urban Communities, from the N.C. Commission of Indian Affairs, 2020. [2]American Indian Tribes in North Carolina Originally published as "The State and Its Tribes" by Gregory A. Richardson Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian, Fall 2005. Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History See also: Native American Settlement [3]; North Carolina's Native Americans (collection page) [4] North Carolina has the largest American Indian population east of the Mississippi River and the eighth-largest Indian population in the United States. As noted by the 2000 U.S. Census [5], 99,551 American Indians lived in North Carolina, making up 1.24 percent of the population. This total is for people identifying themselves as American Indian alone. The number is more than 130,000 when including American Indian in combination with other races. The State of North Carolina recognizes eight tribes: Eastern Band of Cherokee [6] (tribal reservation in the Mountains) Coharie [7] (Sampson and Harnett counties) Lumbee [8] (Robeson and surrounding counties) Haliwa-Saponi [9] (Halifax and Warren counties) Sappony [10] (Person County [11]) Meherrin [12](Hertford and surrounding counties) Occaneechi Band of Saponi Nation [13] (Alamance and surrounding counties) Waccamaw-Siouan [14] (Columbus and Bladen counties) North Carolina also has granted legal status to four organizations representing and providing services for American Indians living in urban areas: Guilford Native American Association (Guilford and surrounding counties), Cumberland County Association for Indian People (Cumberland County), Metrolina Native American Association [15] (Mecklenburg and surrounding counties), and Triangle Native American Society [16] (Wake and surrounding counties). -

SC Native American Entities

Native American Entities Reference Files Updated September 16, 2020 by Archivist Brent Burgin The Native American Studies Archive actively seeks to continually add new material. Contemporary scholarship alongside new finds in recently digitized materials continue to increase our growing knowledge and understanding of Native American History in South Carolina and the Southeastern United States. Journal articles, clippings, photographs, ephemera, tribal correspondence and newsletters comprise this collection. These files are a work in progress. It is hoped that tribal members and leaders will send us copies of tribal newsletters and other archival materials for inclusion. American Indian Chamber of Commerce (AICCSC) (Berkeley County) Beaver Creek Indians (Orangeburg County) Additional materials located in Alice B Kasakoff Collection including tribal history by Melinda Hewitt. These materials apply to several Pee Dee groups. Clippings, 2008 Publications - Newsletter Beaver Creek Indians, 2007- Chaloklowa Chickasaw Indians (Williamsburg County) Catawba Indian Nation (York County) Additional materials located in the Thomas J Blumer, Early Fred Sanders, Steven Guy Baker, Monty Hawk Branham Collections Ephemera: 1st Annual Catawba Pow Wow, April 17-18, 2010. Winthrop Coliseum. Miss Catawba Crowning Ceremony, 2012 Writings: Adams, Mikaëla M (2012) – “Residency and Enrollment: Diaspora and the Catawba Indian Nation” Auguste, Nicol (2009) – “By Her Hands: Catawba Women and Tribal Survival, Civil War Through Reconstruction” Crow, Rosanna (2011) -

Life in the Pee Dee: Prehistoric and Historic Research on the Roche Carolina Tract, Florence County, South Carolina

LIFE IN THE PEE DEE: PREHISTORIC AND HISTORIC RESEARCH ON THE ROCHE CAROLINA TRACT, FLORENCE COUNTY, SOUTH CAROLINA CHICORA FOUNDATION RESEARCH SERIES 39 Front Cover: One of the most interesting artifacts from Chicora's excavations at 38FL240 is this small, stamped brass "circus medallion." The disk shows the profile of an elephant, surrounded by the announcement that the "GREAT EASTERN MENAGERIE MUSEUM AVIARY CIRCUS AND BALLOON SHOW IS COMING." The Great Eastern Circus was only in operation from 1872 through 1874, under the direction of Andrew Haight, who was known as "Slippery Elm" Haight, due to his unsavory business practices. The Circus featured a young elephant named "Bismark" -- probably the very one shown on this medallion. In 1873 the Circus came to Florence, South Carolina, stopping for only two days -- October 18 and 19 -- on its round through the South. It is likely that this brass token was an advertisement for the circus. In this case it was saved, probably by the child of a tenant farmer, and worn as a constant reminder of Bismark, and a truly unusual event for the small, sleepy town of Florence. LIFE IN THE PEE DEE: PREHISTORIC AND HISTORIC RESEARCH ON THE ROCHE CAROLINA TRACT, FLORENCE COUN1Y, SOUTH CAROLINA Research Series 39 Michael Trinkley Debi Hacker Natalie Adams Chicora Foundation, Inc. P.O. Box 8664 • 861 Arbutus Drive Columbia, South Carolina 29202 803/787-6910 Prepared For: Roche Carolina, Inc. Nutley, New Jersey September 1993 ISSN 0082-2041 Library of Congress Cataloging -in -Publication Data Trinkley, Michael. Life in the Pee Dee: prehistoric and historic research on the Roche Carolina tract, Florence County, South Carolina / Michael Trinkley, Debi Hacker, Natalie Adams. -

A Study of the Influence of the Mormon Church on the Catawba Indians of South Carolina 1882-1975

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1976 A Study of the Influence of the Mormon Church on the Catawba Indians of South Carolina 1882-1975 Jerry D. Lee Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Lee, Jerry D., "A Study of the Influence of the Mormon Church on the Catawba Indians of South Carolina 1882-1975" (1976). Theses and Dissertations. 4871. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4871 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 44 A STUDY OF THE theinfluenceINFLUENCE OF THE MORMON CHURCH ON THE CATAWBA INDIANS OF SOUTH CAROLINA 1882 1975 A thesis presented to the department of history brigham young university in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree master of arts by jerryterry D lee december 1976 this thesis by terry D lee is accepted in its present form by the department of history of brigham young university as satisfying the thesis requirement for the degree of master of arts ted T wardwand comcitteemittee chairman r eugeeugenfeeugence E campbell ommiaeommiadcommitcommiliteeCommilC tciteelteee member 0 4 ralphvwitebcwiB smith committee member A 2.2 76 L dandag ted J weamerwegmerwagmer