History of Frontal Concepts Tn Meteorology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Brainstormers the Electromagnetic Field

COMMENT SPRING BOOKS weather forecasting, particularly in the United States. Between the birth of Bjerknes — the oldest — in 1862 and the death of Wexler, the youngest, in 1962, there passed a forma- Inventing tive and innovative Atmospheric century. As Fleming Science: reveals, their lives were Bjerknes, Rossby, linked, with Bjerknes Wexler, and the teaching Rossby and Foundations Rossby, Wexler. of Modern Meteorology In 1904, in ‘Weather JAMES RODGER forecasting as a prob- FLEMING lem in mechanics and MIT Press: 2016. physics’, Bjerknes set the agenda for applying the laws of physics to the atmosphere to predict the weather (V. Bjerknes Meteorol. Z. 21, 1–7; 1904). His vision was to use a sufficiently accurate knowledge of the state of the atmosphere and the laws that govern its evolution to forewarn people about weather to come. His motiva- METEOROLOGY tion was to make his mark in what was for him a new field of science — he began his career working with his father, a physicist at the University of Oslo, on fluid analogies for The brainstormers the electromagnetic field. He was eager, too, to provide practical advice on hazards that affected mariners, farmers and the public. Alan Thorpe enjoys a hymn to some of the founders of Fleming notes the absence of a book-length the science and institutions of weather forecasting. biography of Rossby, and I hope that this will be rectified soon. To me, he is a first among equals. As well as building institutions, he t is thanks to the efforts of an international impacts, mostly on US weather forecasting. -

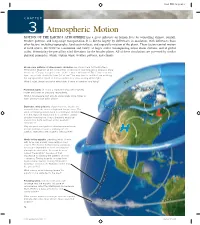

3 Atmospheric Motion

Final PDF to printer CHAPTER 3 Atmospheric Motion MOTION OF THE EARTH’S ATMOSPHERE has a great influence on human lives by controlling climate, rainfall, weather patterns, and long-range transportation. It is driven largely by differences in insolation, with influences from other factors, including topography, land-sea interfaces, and especially rotation of the planet. These factors control motion at local scales, like between a mountain and valley, at larger scales encompassing major storm systems, and at global scales, determining the prevailing wind directions for the broader planet. All of these circulations are governed by similar physical principles, which explain wind, weather patterns, and climate. Broad-scale patterns of atmospheric circulation are shown here for the Northern Hemisphere. Examine all the components on this figure and think about what you know about each. Do you recognize some of the features and names? Two features on this figure are identified with the term “jet stream.” You may have heard this term watching the nightly weather report or from a captain on a cross-country airline flight. What is a jet stream and what effect does it have on weather and flying? Prominent labels of H and L represent areas with relatively higher and lower air pressure, respectively. What is air pressure and why do some areas have higher or lower pressure than other areas? Distinctive wind patterns, shown by white arrows, are associated with the areas of high and low pressure. The winds are flowing outward and in a clockwise direction from the high, but inward and in a counterclockwise direction from the low. -

Estimation of Gravity Wave Momentum Flux with Spectroscopic Imaging

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University Physical Sciences - Daytona Beach College of Arts & Sciences 1-2005 Estimation of Gravity Wave Momentum Flux with Spectroscopic Imaging Jing Tang Farzad Kamalabadi Steven J. Franke Alan Z. Liu Embry Riddle Aeronautical University - Daytona Beach, [email protected] Gary R. Swenson Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.erau.edu/db-physical-sciences Part of the Oceanography and Atmospheric Sciences and Meteorology Commons Scholarly Commons Citation Tang, J., Kamalabadi, F., Franke, S. J., Liu, A. Z., & Swenson, G. R. (2005). Estimation of Gravity Wave Momentum Flux with Spectroscopic Imaging. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 43(1). Retrieved from https://commons.erau.edu/db-physical-sciences/21 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Physical Sciences - Daytona Beach by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON GEOSCIENCE AND REMOTE SENSING, VOL. 43, NO. 1, JANUARY 2005 103 Estimation of Gravity Wave Momentum Flux With Spectroscopic Imaging Jing Tang, Student Member, IEEE, Farzad Kamalabadi, Member, IEEE, Steven J. Franke, Senior Member, IEEE, Alan Z. Liu, and Gary R. Swenson, Member, IEEE Abstract—Atmospheric gravity waves play a significant role waves is quantified by the divergence of the momentum flux. in the dynamics and thermal balance of the upper atmosphere. Using spectroscopic imaging to measure momentum flux will In this paper, we present a novel technique for automated contribute to the understanding of gravity wave processes and and robust calculation of momentum flux of high-frequency their influence on global circulation. -

Climate and Atmospheric Circulation of Mars

Climate and QuickTime™ and a YUV420 codec decompressor are needed to see this picture. Atmospheric Circulation of Mars: Introduction and Context Peter L Read Atmospheric, Oceanic & Planetary Physics, University of Oxford Motivating questions • Overview and phenomenology – Planetary parameters and ‘geography’ of Mars – Zonal mean circulations as a function of season – CO2 condensation cycle • Form and style of Martian atmospheric circulation? • Key processes affecting Martian climate? • The Martian climate and circulation in context…..comparative planetary circulation regimes? Books? • D. G. Andrews - Intro….. • J. T. Houghton - The Physics of Atmospheres (CUP) ALSO • I. N. James - Introduction to Circulating Atmospheres (CUP) • P. L. Read & S. R. Lewis - The Martian Climate Revisited (Springer-Praxis) Ground-based observations Percival Lowell Lowell Observatory (Arizona) [Image source: Wikimedia Commons] Mars from Hubble Space Telescope Mars Pathfinder (1997) Mars Exploration Rovers (2004) Orbiting spacecraft: Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (NASA) Image credits: NASA/JPL/Caltech Mars Express orbiter (ESA) • Stereo imaging • Infrared sounding/mapping • UV/visible/radio occultation • Subsurface radar • Magnetic field and particle environment MGS/TES Atmospheric mapping From: Smith et al. (2000) J. Geophys. Res., 106, 23929 DATA ASSIMILATION Spacecraft Retrieved atmospheric parameters ( p,T,dust...) - incomplete coverage - noisy data..... Assimilation algorithm Global 3D analysis - sequential estimation - global coverage - 4Dvar .....? - continuous in time - all variables...... General Circulation Model - continuous 3D simulation - complete self-consistent Physics - all variables........ - time-dependent circulation LMD-Oxford/OU-IAA European Mars Climate model • Global numerical model of Martian atmospheric circulation (cf Met Office, NCEP, ECMWF…) • High resolution dynamics – Typically T31 (3.75o x 3.75o) – Most recently up to T170 (512 x 256) – 32 vertical levels stretched to ~120 km alt. -

Cumulated Bibliography of Biographies of Ocean Scientists Deborah Day, Scripps Institution of Oceanography Archives Revised December 3, 2001

Cumulated Bibliography of Biographies of Ocean Scientists Deborah Day, Scripps Institution of Oceanography Archives Revised December 3, 2001. Preface This bibliography attempts to list all substantial autobiographies, biographies, festschrifts and obituaries of prominent oceanographers, marine biologists, fisheries scientists, and other scientists who worked in the marine environment published in journals and books after 1922, the publication date of Herdman’s Founders of Oceanography. The bibliography does not include newspaper obituaries, government documents, or citations to brief entries in general biographical sources. Items are listed alphabetically by author, and then chronologically by date of publication under a legend that includes the full name of the individual, his/her date of birth in European style(day, month in roman numeral, year), followed by his/her place of birth, then his date of death and place of death. Entries are in author-editor style following the Chicago Manual of Style (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 14th ed., 1993). Citations are annotated to list the language if it is not obvious from the text. Annotations will also indicate if the citation includes a list of the scientist’s papers, if there is a relationship between the author of the citation and the scientist, or if the citation is written for a particular audience. This bibliography of biographies of scientists of the sea is based on Jacqueline Carpine-Lancre’s bibliography of biographies first published annually beginning with issue 4 of the History of Oceanography Newsletter (September 1992). It was supplemented by a bibliography maintained by Eric L. Mills and citations in the biographical files of the Archives of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UCSD. -

THE 19Th CENTURY GERMAN DIARY of a NEW JERSEY GEOLOGIST

THE 19th CENTURY GERMAN DIARY OF A NEW JERSEY GEOLOGIST BY WILLIAM J. CHUTE WILLIAM J. CHUTE, formerly an Instructor in History at Rutgers, is now a member of the history faculty at Queens Collegey New York. N THE FALL of 1852 a young New Jersey scientist William Kitchell, 25 years of age, embarked for Germany in the fashion I of the day to acquire the advanced training which would pre- pare him for his position as professor of geology at the Newark Wesleyan Institute. He was accompanied by a friend, William H. Bradley, and upon arrival both matriculated at the Royal Saxon Mining Academy at Freiburg near Dresden. Sporadically during the next year and a half, Kitchell jotted down his impressions of a multitude of things in a diary—now in the possession of the Rutgers University Library. While his descriptive powers were limited and his style of writing would have received no prize for polish, the diary is informative and entertaining—the personal sketches of world famous men of science, the prevalence of soldiers in Berlin, the hor- rible climate, the slowness of transportation, his questioning of the authenticity of the Genesis story of the great flood are as interesting as the comical and persistent match-making innuendoes of his land- lady and the undisguised matrimonial suggestions of her unblushing daughter. Anecdotes of his American friends who later achieved re- nown are a welcome contribution to the biographer. Kitchell's own claim to fame was won as the director of the New Jersey Geological Survey begun in 1854. -

Bierknes Memorial Lecture Richard J

Bierknes Memorial Lecture Richard J. Reed1 The Development and Status of Modern Weather Prediction2 Abstract or writings. Despite his many accomplishments and honors, Bjerknes was a modest man. I trust that he The progress made in weather prediction since national would approve of our decision to focus attention in this weather services began issuing forecasts is traced and assessed. Specific contributions of J. Bjerknes to this program are lecture on the subject to which he devoted much of his pointed out. Lessons learned from the historical record con- life's work rather than on his personal achievements cerning factors and conditions responsible for the important alone. advances are considered, and a limited evaluation is then During the period under consideration, weather fore- made of the increase in forecast skill that resulted from these advances. Finally, some comments are offered on the future casting was transformed from a practical art to a partly prospects of weather prediction. quantitative science. Thus it will be convenient in the discussion that follows to divide the period into three eras: a first extending from 1860 to 1920 in which fore- 1. Introduction cast practice was based almost entirely on human ex- We gather tonight to celebrate the memory of Jacob perience and skill, a second extending from 1920 to 1950 Bjerknes, one of the towering figures in the history of in which physical concepts received increasing emphasis, meteorology. In a long and distinguished career that and finally the modern era in which physical-numerical spanned a period of more than 50 years, Bjerknes made methods have been introduced and become firmly es- monumental contributions to our knowledge and under- tablished. -

NWS Unified Surface Analysis Manual

Unified Surface Analysis Manual Weather Prediction Center Ocean Prediction Center National Hurricane Center Honolulu Forecast Office November 21, 2013 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Surface Analysis – Its History at the Analysis Centers…………….3 Chapter 2: Datasets available for creation of the Unified Analysis………...…..5 Chapter 3: The Unified Surface Analysis and related features.……….……….19 Chapter 4: Creation/Merging of the Unified Surface Analysis………….……..24 Chapter 5: Bibliography………………………………………………….…….30 Appendix A: Unified Graphics Legend showing Ocean Center symbols.….…33 2 Chapter 1: Surface Analysis – Its History at the Analysis Centers 1. INTRODUCTION Since 1942, surface analyses produced by several different offices within the U.S. Weather Bureau (USWB) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA’s) National Weather Service (NWS) were generally based on the Norwegian Cyclone Model (Bjerknes 1919) over land, and in recent decades, the Shapiro-Keyser Model over the mid-latitudes of the ocean. The graphic below shows a typical evolution according to both models of cyclone development. Conceptual models of cyclone evolution showing lower-tropospheric (e.g., 850-hPa) geopotential height and fronts (top), and lower-tropospheric potential temperature (bottom). (a) Norwegian cyclone model: (I) incipient frontal cyclone, (II) and (III) narrowing warm sector, (IV) occlusion; (b) Shapiro–Keyser cyclone model: (I) incipient frontal cyclone, (II) frontal fracture, (III) frontal T-bone and bent-back front, (IV) frontal T-bone and warm seclusion. Panel (b) is adapted from Shapiro and Keyser (1990) , their FIG. 10.27 ) to enhance the zonal elongation of the cyclone and fronts and to reflect the continued existence of the frontal T-bone in stage IV. -

The History of Weather Prediction

Haley Cica 14 September 2009 Willard Clark Intro into Integrated Science Nicholas Scaturo Paper 1 The History of Weather Prediction The article “ The origins of computer weather prediction and climate modeling” by Peter Lynch is about all of the different people who made possible the current understanding of the world weather and the ability to predict it by making giant leaps in both mathematics, hydrodynamics, and computer technology. No one man could have made this possible; it took the life’s work of many different men to make weather prediction and understanding a reality. It all started with the development of thermodynamics and hydrodynamics. Then came three men who might be considered the founding fathers of weather prediction, these men were Cleveland Abbe, Vilhelm Bjerknes, and Lewis Fry Richardson. In 1901 Cleveland Abbe wrote a paper titled “ The physical basis of long-range weather forecasting” which proposed using mathematics to predict weather. Not long after, Vilhelm Bjerknes, a Norwegian scientist introduced a plan to predict weather which included two steps: To observe the atmosphere, then calculate movement using the laws of motion. In 1922, while working at the Meteorological Office in, Lewis Fry Richardson wrote a book titled “ Weather Prediction by Numerical Process” where he criticized the then current practice of using an “ Index of Weather Maps” to predict weather by finding a previous map that resembled your current map and deducing that the weather will act in a similar manner. This method was of course highly inaccurate as Richardson points out. He then laid out a forecasting scheme which was based on Bjerknes’ program and involved an unimaginable volume of numerical computation which he realized would be practically impossible without computers. -

ESSENTIALS of METEOROLOGY (7Th Ed.) GLOSSARY

ESSENTIALS OF METEOROLOGY (7th ed.) GLOSSARY Chapter 1 Aerosols Tiny suspended solid particles (dust, smoke, etc.) or liquid droplets that enter the atmosphere from either natural or human (anthropogenic) sources, such as the burning of fossil fuels. Sulfur-containing fossil fuels, such as coal, produce sulfate aerosols. Air density The ratio of the mass of a substance to the volume occupied by it. Air density is usually expressed as g/cm3 or kg/m3. Also See Density. Air pressure The pressure exerted by the mass of air above a given point, usually expressed in millibars (mb), inches of (atmospheric mercury (Hg) or in hectopascals (hPa). pressure) Atmosphere The envelope of gases that surround a planet and are held to it by the planet's gravitational attraction. The earth's atmosphere is mainly nitrogen and oxygen. Carbon dioxide (CO2) A colorless, odorless gas whose concentration is about 0.039 percent (390 ppm) in a volume of air near sea level. It is a selective absorber of infrared radiation and, consequently, it is important in the earth's atmospheric greenhouse effect. Solid CO2 is called dry ice. Climate The accumulation of daily and seasonal weather events over a long period of time. Front The transition zone between two distinct air masses. Hurricane A tropical cyclone having winds in excess of 64 knots (74 mi/hr). Ionosphere An electrified region of the upper atmosphere where fairly large concentrations of ions and free electrons exist. Lapse rate The rate at which an atmospheric variable (usually temperature) decreases with height. (See Environmental lapse rate.) Mesosphere The atmospheric layer between the stratosphere and the thermosphere. -

Ocean Circulation and Climate: a 21St Century Perspective

Chapter 13 Western Boundary Currents Shiro Imawaki*, Amy S. Bower{, Lisa Beal{ and Bo Qiu} *Japan Agency for Marine–Earth Science and Technology, Yokohama, Japan {Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, Massachusetts, USA {Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, University of Miami, Miami, Florida, USA }School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii, USA Chapter Outline 1. General Features 305 4.1.3. Velocity and Transport 317 1.1. Introduction 305 4.1.4. Separation from the Western Boundary 317 1.2. Wind-Driven and Thermohaline Circulations 306 4.1.5. WBC Extension 319 1.3. Transport 306 4.1.6. Air–Sea Interaction and Implications 1.4. Variability 306 for Climate 319 1.5. Structure of WBCs 306 4.2. Agulhas Current 320 1.6. Air–Sea Fluxes 308 4.2.1. Introduction 320 1.7. Observations 309 4.2.2. Origins and Source Waters 320 1.8. WBCs of Individual Ocean Basins 309 4.2.3. Velocity and Vorticity Structure 320 2. North Atlantic 309 4.2.4. Separation, Retroflection, and Leakage 322 2.1. Introduction 309 4.2.5. WBC Extension 322 2.2. Florida Current 310 4.2.6. Air–Sea Interaction 323 2.3. Gulf Stream Separation 311 4.2.7. Implications for Climate 323 2.4. Gulf Stream Extension 311 5. North Pacific 323 2.5. Air–Sea Interaction 313 5.1. Upstream Kuroshio 323 2.6. North Atlantic Current 314 5.2. Kuroshio South of Japan 325 3. South Atlantic 315 5.3. Kuroshio Extension 325 3.1. -

275 Tor Bergeron's Uber Die

JULY,1931 MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW 275 The aooperative stations are nearer the c.rops, being gage: These are read at about 4 p. m. or 8 a. m. and the mostly in small towns, or even on farms, in some in- maximum and niininiuin temperature, set maximum stances, but they measure only rainfall and temperature temperature, and total rainfall entered on forms. Where once a day and have no self-recording instruments that are the details? How much sunshine, what was soil keep a continuous record. Thus, for these which are temperature, when did rain occur, how long were tempera- more directly applicable, many weather phases are not tures above or below a significant value, what was the available. relative humidity, rate of evaporation, etc.? The crop statistics are even more hazy and generalized, Even if the above questions were satisfactorily answered in addition to being relatively inaccessible. We can find how can we be sure that, we have everything we need? easily the estimated yield per acre or total acreage, for the Maybe we need leaf temperature, intensity of solar radia- most available data give these figures on a State unit tion, plant transpiration, moisture of tlie soil at different basis, but yields often vary widely in different parts of a depths, and many other details too numerous to mention. State. Loc,al, even in most places county, temperature and rainfall data are available, but what about correspond- CONCLUSION ing yield figures? They are to be had in some individual Are we doing everything possible to facilitate the study State publications, but a complete file for one State is OI crop production in its relation to the weather on a difficult to find outside the issuing office and then the large scale, or even in local areas? There have been some series is rarely carried back far enough to be of material beginnings.