Sublimity and the Bow Chime Poole, A.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LA MUSICA D'avanguardia (Provenienza Sconosciuta

LA MUSICA D’AVANGUARDIA (provenienza sconosciuta!!) Presentazione Questo volume si propone di fornire una panoramica, la piu' aggiornata possibile, sui fenomeni musicali che esulano dalle correnti tradizionali del rock, del jazz e della classica, e che rappresentano in senso lato l'attuale "avanguardia". In tal senso l'avanguardia, piu' che un movimento monolitico e omogeneo, appare come una federazione piu' o meno aperta di tante scuole diverse e separate. Alcune costituiscono la cosiddetta "contemporanea" (capitoli 1-7), figlia dell'avanguardia classica; altre sono scaturite della sperimentazione dei complessi rock (capitoli 8-10); altre ancora appartengono al nuovo jazz, e non fanno altro che legittimare una volta per tutte il jazz nel novero della musica "intellettuale" (capitoli 11-13); la new age, infine, sfrutta le suggestioni delle scuole precedenti (capitoli 14-17). Piuttosto che un'introduzione generale ci sembra allora piu' opportuno fornire una presentazione capitolo per capitolo: 1. L'avanguardia popolare. Per avanguardia si intendeva un tempo soltanto l'avanguardia classica. A dimostrazione di come i tempi siano cambiati, questo libro e' in gran parte dedicato a musicisti che hanno le loro origini nel rock, nel jazz o nella new age. In questo primo capitolo ci proponiamo di fornire una panoramica storica sulla nascita dei movimenti musicali che hanno introdotto le novita' armoniche, acustiche, ideologiche su cui speculano tuttora gli sperimentatori moderni. Ci premeva anche trasmettere la sensazione che esista una qualche continuita' fra i lavori di Varese e Stockhausen (per citarne due particolarmente famosi) e i protagonisti di questo libro. 2. Minimalismo. La scuola minimalista degli anni Settanta era chiaramente delimitata. -

Almanac, 05/24/94, Vol. 40, No. 34

INSIDE • Senate: More Nominations, p. 2 • Of Record: Faculty Grievance Changes, p. 2 • A-3 Assembly: Thanks and What’s Next, p. 2 • Commencement in Speech & Song, pp. 3-7 • Honors & Other Things, pp. 8-11 • Speaking Out, pp. 12-13 • Council May 14: Revlon, ROTC, Etc., p. 13 • Of Record: Electronic Records, p. 14 • Of Record: Recognized Holidays, p. 15 • CrimeStats, Bulletins, p. 15 • Benchmarks: Dr. Cisneros is Proud.... p. 16 Pullout: Summer at Penn Tuesday, May 24, 1994 Published by the University of Pennsylvania Volume 40 Number 34 Teaching Award in Nursing: Kathryn Sabatino Kathryn Sabatino (right), clinical instructor at the School of Nursing, has been named recipient of the School’s 1994 Teaching Award. Ms. Sabatino received the award at the School’s Commencement on May 18. Her students said she is “equally adept in many teaching settings. In all cases her teaching is notably coherent and intellectually challenging, coupled with a personal, honest caring for her students and the material.” Established in 1983, the award is presented annually to a faculty member for excellence in classroom and/or clinical teaching. Ms. Sabatino joined the nursing faculty as a part-time clinical instruc- tor-lecturer in September 1990. She teaches sophomore students in their first in-hospital clinical nursing courses. In addition to serving on the faculty and teaching courses in nursing theory and practice, physiology and physical examination, Ms. Sabatino is a clinical nurse specialist in surgical nursing at HUP. As a clinical nurse specialist she is involved in patient care as well as nursing staff education and research. -

No. 23 February 24, 1981

Tuesday, February 24, 1981 Volume 27, Number 23 Affirmative Action: Provost's Search: Call for Nominations First The Consultative Committee on the Selection of a Provost requests that nominations or Substance for the with documents, be sent by March 10, applications position, supporting Tuesday. At the end of Wednesday's meeting with to Professor Irving B. Kravis, in care of the Office of the Secretary, 121 College Hall/CO. some 30 faculty, staff and student members of Members of the community also are encouraged to make formal or informal University the University interested in affirmative action, to other members of the committee. Members include: suggestions President Sheldon Hackney announced that will with Irving B. Kravis, University Professor of Economics, chairman the University proceed the imple- mentation of its affirmative action March Jacob M. Abel, associate professor and chairman of mechanical engineering plan Diana L. Bucolo, FAS' 83 2, without waiting for final sign-off on data the of Federal Contract Dr. Peter A. Cassileth, professor of hematology-oncology displays by Office Helen C. Davies, associate professor of microbiology Compliance Programs. 2, Dr. on Irwin Friend, Edward J. Hopkinson Professor of Finance and Economics On page Hackney reports that and its for decision-mak- Henry B. Hansmann, assistant professor of law meeting implications Robert F. Lucid, professor and chairman of English ing styles. 'The sense of the was that we Larry Masuoka, Dental '83 meeting should not lose time in the substantive areas George Rochberg, Annenberg Professor of Humanities and Composer in Residence while for technical data to be Rosemary A. -

1985-87 Catalogue and Calendar

Lincoln University 1985-87 Catalogue and Calendar On the covers and catalogue pages: The front and back covers of the 1985-87 Lincoln University Catalogue and Calendar depict a campus scene at the historic college in Chester County, PA, with its harmonious blend of renovated and modern structures. The renovated historic buildings shown (L-R) are: Amos Hall dormitory, Houston Hall dormitory, Vail Memorial Hall administrative building, and Cresson Hall dormitory. The photograph was taken by Jerome Harden, a former student. Additional photographs contained in the catalogue were taken also by Harden, campus photographer Milton Barbehenn, and others. Lincoln University, in compliance with Title IX of the Education Amendment of 1972 and other Civil Rights laws, offers equal opportunity for admission and employment. Moreover, the programs and activities of the University are offered to all students without regard to race, color, national origin, religion, age, physical disability I o receive an application packet, or more information on the University, write: LINCOLN UNIVERSITY A commitment to quality education since 1854. of the Commonwealth System Lincoln University of High er Education Office of Admissions Lincoln University, PA 19352 Or call (in Philadelphia) WA 5-9440, or (215) 932-8300 Lincoln University 1985-87 Catalogue & Calendar Published by the Department of Public Relations and Publications Sam W. Pressley, Director (Special thanksalso to Mrs. Sophy H. Cornwell,and Mrs. Janet E. Robinson) ^ I 1-—. Jl Table of Contents 1985-87 Trimester -

A Survey of Contemporary Sound Sculpture a Thesis

A SURVEY OF CONTEMPORARY SOUND SCULPTURE A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE TEXAS WOMAN'S UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF HUMANITIES AND FINE ARTS BY JAMES A. ESTES, B.A. DEN':I'ON, TEXAS MAY, 1987 TEXAS WOMAN'S UNIVERSITY Denton Texas April 22, 1987 To the Provost of the Graduate School: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by James A. Estes entitled "A Survey of Contemporary Sound Sculpture." I have Examined the final copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in/// = :... ��Gr- e"" e:::::::: �n:::,�Ma==j =o=r==Pro_ f_ _e_s_s_ o_r _ We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance Accepted Provost of the Gradrlate School __ _ ABSTRACT Sound sculpture and other closely related artforms have become increasingly prevalent within the last few decades. By means of a questionnaire, this study surveyed artists who use sound as an essential aspect of their work. The questionnaire was designed to establish some of the basic parameters and attributes of the current activity in the field, including type of work, artist and exhibition histories, economic support and audience profiles. In this way, the findings address the fundamental questions of who, what, when, where and how, both for individual artists and the group as a whole. The results of the study suggest the need of continued research founded on an interdisciplinary perspective in order to fully address the broader topics and scope of this genre. -

John Duncan Exhibitions

1 October JOHN DUNCAN MANTRA solo concert Fylkingen, Stockholm Curated by Joachim Nordwall EXHIBITIONS and CONCERTS 2017 19 – 20 January 12 - 16 October MANTRA solo concert + workshop WORDS BROKEN VOICE MISSING MESSAGE KHM Köln FAILED workshop + concert Curated by Hans W. Koch + Dirk Specht Cirkulacija2, Ljubljana Curated by Stefan Doepner 25 January – 15 February JOHN DUNCAN: HEAVY, USELESS, NO SENSE OF 24 October HUMOR Concert with Eiko Ishibashi Trio + G. di Domenico Solo exhibition Il Torrione, Ferrara Narkissos Gallery, Bologna Curated by Eiko Ishibashi Curated by Yelena Mitrjushkina 11 November 17 June – 10 October John Duncan Films The Nazca Transmissions included in Alienation: First Street Studio, Austin Momentum 9 Biennial Curated by Tara Battacharya Reed for Antumbrae Moss, Norway Intermedia Curated by Jacob Lillemose 12 November 2016 MANTRA solo concert 5 - 8 May First Street Studio, Austin AngelicA 2016 Curated by Tara Battacharya Reed for Antumbrae Ellen Fullman solo + Konrad Spengler duet Intermedia James Hamilton, France Jobin, Carine Masutti Sons of God + TERRA AMARA: John Duncan with 2015 Coro Arcanto 15 January - 28 February Teatro San Leonardo, Bologna The NAZCA TRANSMISSIONS LP included in Fühlst Curated by John Duncan du Nicht an Meinen Liedern dass Ich Eins und Doppelt Bin 13 May Gallery Peter Kilchmann, Zurich RED SKY included in KREV events Curated by Mateo Chacon-pino and Adriana Dada 100 Years Dominguez Cabaret Voltaire, Zurich Other artists include Michael Najjar, Maria Garcia Curated by Adrian Notz Ibañez, -

Rediscovering the Interpersonal: Models of Networked

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library Summer 8-2-2018 Rediscovering The nI terpersonal: Models Of Networked Communication In New Media Performance Alicia Champlin University of Maine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Art Practice Commons, Audio Arts and Acoustics Commons, Composition Commons, Digital Humanities Commons, Graphics and Human Computer Interfaces Commons, Harmonic Analysis and Representation Commons, Interactive Arts Commons, Interdisciplinary Arts and Media Commons, Music Performance Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Music Commons, Performance Studies Commons, Philosophy of Language Commons, and the Theory and Algorithms Commons Recommended Citation Champlin, Alicia, "Rediscovering The nI terpersonal: Models Of Networked Communication In New Media Performance" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2922. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/2922 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REDISCOVERING THE INTERPERSONAL: MODELS OF NETWORKED COMMUNICATION IN NEW MEDIA PERFORMANCE By Alicia B. Champlin B.A. University of Maine, 2015 A THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts (in Intermedia) The Graduate School The University of Maine August 2018 Advisory Committee: N. B. Aldrich, Adjunct Assistant Professor of Intermedia (Co-Advisor) Joline Blais, Associate Professor of New Media (Co-Advisor) Amy O. Pierce, Adjunct Assistant Professor of New Media Sofian Audry, Assistant Professor of New Media Jon Ippolito, Professor of New Media © 2018 Alicia B. -

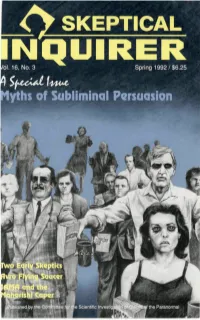

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER V01.16, No

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER V01.16, No. 3 Spring 1992/$6.25 Myths of Subliminal Persuasion the Paranormal MM THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER (ISSN 0194-6730) is the official journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal, an international organization. Editor Kendrick Frazier. Editorial Board James E. Alcock, Martin Gardner, Ray Hyman, Philip J. Klass, Paul Kurtz. Consulting Editors Isaac Asimov, William Sims Bainbridge, John R. Cole, Kenneth L. Feder, C. E. M. Hansel, E. C. Krupp, David F. Marks, Andrew Neher, James E. Oberg, Robert Sheaffer, Steven N. Shore. Managing Editor Doris Hawley Doyle. Contributing Editor Lys Ann Shore. Business Manager Mary Rose Hays. Assistant Business Manager Sandra Lesniak Chief Data Officer Richard Seymour. Computer Assistant Michael Cione. Production Paul E. Loynes. Audio Technician Vance Vigrass. Librarian, Ranjit Sandhu. Staff Leland Harrington, Alfreda Pidgeon, Kathy Reeves, Elizabeth Begley (Albuquerque). Cartoonist Rob Pudim. The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, State University of New York at Buffalo. Barry Karr, Executive Director and Public Relations Director. Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director. Fellows of the Committee (partial list) James E. Alcock, psychologist, York Univ., Toronto; Isaac Asimov, biochemist, author; Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of Kentucky; Irving Biederman, psychologist, University of Minnesota; Susan Blackmore, psychologist, Brain Perception Laboratory, University of Bristol, England; Henri Broch, physicist, University of Nice, France; Mario Bunge, philosopher, McGill University; John R. Cole, anthropologist. Institute for the Study of Human Issues; F. H. C. Crick, biophysicist, Salk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla, Calif.; L. -

2002 Annual Report

THE COMMUNITY FOUNDATION Non Profit Org. of Southeastern Connecticut Bulk Rate 147 State Street, P.O. Box 769 U.S. Postage New London, CT 06320 PAID (860) 442-3572 Permit 101 www.cfsect.org New London, CT 06320 The Community Foundation of Southeastern Connecticut 2002 ANNUAL REPORT “A thousand strands of hope... THE COMMUNITY FOUNDATION of Southeastern Connecticut THE MISSION OF THE COMMUNITY FOUNDATION The Community Foundation’s mission is to connect donors with opportunities that promote the common good of the residents of Southeastern Connecticut. We encourage local philanthropy and award grants and scholarships by building a permanent endowment for the community. 2002 ANNUAL REPORT “A thousand strands of hope... entwined in a cable of strength” THE COMMUNITY FOUNDATION of Southeastern Connecticut TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the President . .3 Towns served by The Community Foundation of Southeastern Connecticut: Highlights . .4–8 East Lyme 2002 Grants . .9–11 Groton Women & Girls Fund Grants . .12 Ledyard 2002 Scholarships . .13, 14 Lyme 2002 Funds . .15–17 2002 Gifts . .18–24 Montville The Legacy Society/Professional Advisory Council . .25 New London North Stonington Tributes & Memorials . .26 Old Lyme Women & Girls Founding Members . .27 Salem 2002 Stewardship . .28, 29 Stonington Connecting with the Community . .30, 31 Waterford Board of Trustees, Committees and Staff . .32 2 THE COMMUNITY FOUNDATION OF SOUTHEASTERN CONNECTICUT A LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT Dear Friends of the Foundation, As I reflect on the past year at The Community Foundation and the privilege of serving as its president many images flood my memory. I begin with our own splendid new building at 147 State Street. -

The Voice of New Music

TOM Title The Voice of New Music by Tom Johnson New York City 1972-1982 JOHNSON A collection of articles originally published in the Village Voice Author Tom Johnson Drawings HE OICE Tom Johnson (from his book Imaginary Music, published by Editions 75, 75, rue T V de la Roquette, 75011 Paris, France) Publisher Editions 75 Editors OF NEW Tom Johnson, Paul Panhuysen Coordination HélènePanhuysen Word processing MUSIC Marja Stienstra NEW YORK CITY 1972 - 1982 File format translation Matthew Rogalski A COLLECTION OF ARTICLES ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN THE VILLAGE VOICE Digital edition Javier Ruiz Reprinted with permission of the author and the Village Voice ©1989 All rigths reserved [NEW DIGITQL EDITION BASED IN THE 1989 EDITION BY HET APOLLOHUIS] [Het Apollohuis edition: ISBN 90-71638-09-X] for all of those whose and for all that I ideas and energies learned from them became the voice of new music, Editions 75, 75 rue de la Roquette, 75011 PARIS http://www.tom.johnson.org/ Preface Index Introduction Index Index 1972 Index 1973 Index 1974 Index Index 1975 Index 1976 Index 1977 Index Index 1978 Index 1979 Index Index 1980 Index 1981 Index 1982 Music Columns in the Voice Editions 75, 75 rue de la Roquette, 75011 PARIS http://www.tom.johnson.org/ the Western musical tradition and to remove the barriers between different cultures and various artistic disciplines. That process is still in full swing. Therefore it is of interest today to read how that process was triggered. Tom Johnson has been the first champion of this new movement in music. -

THE 11Th ANNUAL AVANT G/ARDE FESTIVAL of NEW YORK - the VIDEO PROGRAM

47west46th new york10036 PL,-, NS FOR THE 11th ANNUAL AVANT G/ARDE FESTIVAL OF NEW YORK - THE VIDEO PROGRAM You have probably already received an invitation to participate in the 11th Annual Avant Garde Festival, to be held November 16, at Shea Stadium in Flushing (Queens), New York . In the event that you cannot, or do not, wish to do your own video piece or installation, we would like to show a videotape of yours as part of a continuous 12hr group video showing . We will be equipped to present EIAJ 2" color and 4" videocassette format tapes, displayed by one or two color video projectors (eg . Sony or Advent) in the Press Room at Shea Stadium . Because of time pressures, it will be difficult to show works longer than 30 minutes . If you would like to participate in the Festival group video program, please send in the title of your work, length, production credits, special playback instructions and any other information you consider important about your tape as soon as possible . We could also use brief biographical material and your autograph for our brochure . We would appreciate that all tapes arrive by Thursday, November 7 c/o Annual Avant Garde Festival, 47 West 46th street, (Apt . 3-R), NYC, NY, 10036 . Where possible, send first generation copies of your master . Your tape will be returned immediately after the one-day Festival and we guarantee that no other use will be made of it beyond the specific November 16 showing . The group video program is one of the most popular events at the Festival which is always free to the public (attendance at recent Festivals has exceeded the 10,000 figure) . -

Kenneth Goldsmith

6799 Kenneth Goldsmith zingmagazine 2000 for Clark Coolidge 45 John Cage 42 Frank Zappa / Mothers 30 Charles Ives 28 Miles Davis 26 James Brown 25 Erik Satie 24 Igor Stravinsky 23 Olivier Messiaen 23 Neil Young 23 Kurt Weill 21 Darius Milhaud 21 Bob Dylan 20 Rolling Stones 19 John Coltrane 18 Terry Riley 18 Morton Feldman 16 Rod McKuen 15 Thelonious Monk 15 Ray Charles 15 Mauricio Kagel 13 Duke Ellington 3 A Kombi Music to Drive By, A Tribe Called Quest M i d n i g h t Madness, A Tribe Called Quest People’s Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm, A Tribe Called Quest The Low End Theory, Abba G reatest Hits, Peter Abelard Monastic Song, Absinthe Radio Trio Absinthe Radio Tr i o, AC DC Back in Black, AC DC Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap, AC DC Flick of the Switch, AC DC For Those About to Rock, AC DC Highway to Hell, AC DC Let There Be R o c k, Johnny Ace Again... Johnny Sings, Daniel Adams C a g e d Heat 3000, John Adams Harmonium, John Adams Shaker Loops / Phrygian Gates, John Luther Adams Luther Clouds of Forgetting, Clouds of Unknowing, King Ade Sunny Juju Music, Admiral Bailey Ram Up You Party, Adventures in Negro History, Aerosmith Toys in the Attic, After Dinner E d i t i o n s, Spiro T. Agnew S p e a k s O u t, Spiro T. Agnew The Great Comedy Album, Faiza Ahmed B e s a r a h a, Mahmoud Ahmed E re Mela Mela, Akita Azuma Haswell & Sakaibara Ich Schnitt Mich In Den Finger, Masami Akita & Zbigniew Karkowski Sound Pressure Level, Isaac Albéniz I b e r i a, Isaac Albéniz Piano Music Volume II, Willy Alberti Marina, Dennis Alcapone Forever Version, Alive Alive!, Lee Allen Walkin’ with Mr.