Friction Between Cultural Representation and Visual Representation with Reference to Padmaavat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Movie Aquisitions in 2010 - Hindi Cinema

Movie Aquisitions in 2010 - Hindi Cinema CISCA thanks Professor Nirmal Kumar of Sri Venkateshwara Collega and Meghnath Bhattacharya of AKHRA Ranchi for great assistance in bringing the films to Aarhus. For questions regarding these acquisitions please contact CISCA at [email protected] (Listed by title) Aamir Aandhi Directed by Rajkumar Gupta Directed by Gulzar Produced by Ronnie Screwvala Produced by J. Om Prakash, Gulzar 2008 1975 UTV Spotboy Motion Pictures Filmyug PVT Ltd. Aar Paar Chak De India Directed and produced by Guru Dutt Directed by Shimit Amin 1954 Produced by Aditya Chopra/Yash Chopra Guru Dutt Production 2007 Yash Raj Films Amar Akbar Anthony Anwar Directed and produced by Manmohan Desai Directed by Manish Jha 1977 Produced by Rajesh Singh Hirawat Jain and Company 2007 Dayal Creations Pvt. Ltd. Aparajito (The Unvanquished) Awara Directed and produced by Satyajit Raj Produced and directed by Raj Kapoor 1956 1951 Epic Productions R.K. Films Ltd. Black Bobby Directed and produced by Sanjay Leela Bhansali Directed and produced by Raj Kapoor 2005 1973 Yash Raj Films R.K. Films Ltd. Border Charulata (The Lonely Wife) Directed and produced by J.P. Dutta Directed by Satyajit Raj 1997 1964 J.P. Films RDB Productions Chaudhvin ka Chand Dev D Directed by Mohammed Sadiq Directed by Anurag Kashyap Produced by Guru Dutt Produced by UTV Spotboy, Bindass 1960 2009 Guru Dutt Production UTV Motion Pictures, UTV Spot Boy Devdas Devdas Directed and Produced by Bimal Roy Directed and produced by Sanjay Leela Bhansali 1955 2002 Bimal Roy Productions -

Anthoney Udel 0060D

INCLUSION WITHOUT MODERATION: POLITICAL VIOLENCE AND DEMOCRATIC PARTICIPATION BY RELIGIOUS GROUPS by Cheryl Mariani Anthoney A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science and International Relations Spring 2018 © 2018 Cheryl Anthoney All Rights Reserved INCLUSION WITHOUT MODERATION: POLITICAL VIOLENCE AND DEMOCRATIC PARTICIPATION BY RELIGIOUS GROUPS by Cheryl Mariani Anthoney Approved: __________________________________________________________ David P. Redlawsk, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of Political Science and International Relations Approved: __________________________________________________________ George H. Watson, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: __________________________________________________________ Ann L. Ardis, Ph.D. Senior Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: __________________________________________________________ Muqtedar Khan, Ph.D. Professor in charge of dissertation I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: __________________________________________________________ Stuart Kaufman, -

Jodhaa Akbar

JODHAA AKBAR ein Film von Ashutosh Gowariker Indien 2008 ▪ 213 Min. ▪ 35mm ▪ Farbe ▪ OmU KINO START: 22. Mai 2008 www.jodhaaakbar.com polyfilm Verleih Margaretenstrasse 78 1050 Wien Tel.:+43-1-581 39 00-20 www:polyfilm.at [email protected] Pressebetreuung: Allesandra Thiele Tel.:+43-1-581 39 00-14 oder0676-3983813 Credits ...................................................2 Kurzinhalt...............................................3 Pressenotiz ............................................3 Historischer Hintergrund ........................3 Regisseur Ashutosh Gowariker..............4 Komponist A.R. Rahman .......................5 Darsteller ...............................................6 Pressestimmen ......................................9 .......................................................................................Credits JODHAA AKBAR Originaltitel: JODHAA AKBAR Indien 2008 · 213 Minuten · OmU · 35mm · FSK ab 12 beantragt Offizielle Homepage: www.jodhaaakbar.com Regie ................................................Ashutosh Gowariker Drehbuch..........................................Ashutosh Gowariker, Haidar Ali Produzenten .....................................Ronnie Screwvala and Ashutosh Gowariker Musik ................................................A. R. Rahman Lyrics ................................................Javed Akhtar Kamera.............................................Kiiran Deohans Ausführende Produzentin.................Sunita Gowariker Koproduzenten .................................Zarina Mehta, Deven Khote -

Page9final.Qxd (Page 1)

DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 15, 2018 (PAGE 9) TENTH DAY KRIYA Sena flays Govt for not permitting Karni Sena stopped at Lakhanpur With profound grief and sorrow we inform Excelsior Correspondent at Lakhanpur by Kathua Police the sad and untimely demise of our beloved Lal Chowk flag hoisting led by DySP, Gourav Mahajan. Smt. Gouri Raina (Ganjoo) W/o Sh. KATHUA, Aug 14: A group They raised slogans while Makhan Lala Ganjoo R/o H.No. 11, Lane Excelsior Correspondent BJP is doing nothing while in of Karni Sena which reached Government and, is also not taking the National Flag in their No. 3, Anant Vihar Lale-Da-Bhag Jammu. here today from Jaipur, JAMMU, Aug 14: Shiv permitting our party leaders to hands and chanted Bharat Mata 10th Day Kriya will be performed on Rajasthan to hoist the National Sena (Bala Sahib Thackery) hoist National Flag at Lal Ki Jai. The Sandhya Rajput team 20.08.2018 (Monday) at Muthi Ghat at here today flayed the Central 8;30 AM. Chowk in Srinagar,” he main- * Watch video on leader took serious exception Government for not giving per- GRIEF STRICKEN tained. www.excelsiornews.com and criticized the administration Sh. Makhan Lala Ganjoo (Husband) mission to its leaders for unfurl- Kohli further said that NDA for not allowing them to march Flag at Lal Chowk, Srinagar in Sanjay Ganjoo & Seema Ganjoo (Son & Daughter-in-Law) Smt. Gouri Raina (Ganjoo) ing National Flag at Kashmir’s Government is appeasing sepa- towards the Lal Chowk Srinagar. Smt. Sunita Raina & P.N Raina (Daughter and Son - in - Law) Lal Chowk to celebrate ratists. -

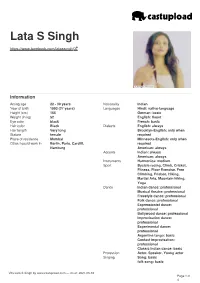

Lata S Singh

Lata S Singh https://www.facebook.com/latassingh © All Rights Reserved Information Acting age 22 - 30 years Nationality Indian Year of birth 1993 (27 years) Languages Hindi: native-language Height (cm) 166 German: basic Weight (in kg) 52 English: fluent Eye color black French: basic Hair color Black Dialects English: always Hair length Very long Brooklyn-English: only when Stature female required Place of residence Mumbai Minnesota-English: only when Cities I could work in Berlin, Paris, Cardiff, required Hamburg American: always Accents Indian: always American: always Instruments Harmonica: medium Sport Bycicle racing, Climb, Cricket, Fitness, Floor Exercise, Free Climbing, Frisbee, Hiking, Martial Arts, Mountain hiking, Yoga Dance Indian dance: professional Musical theatre: professional Freestyle dance: professional Folk dance: professional Expressionist dance: professional Bollywood dance: professional Improvisation dance: professional Experimental dance: professional Argentine tango: basic Contact Improvisation: professional Classic Indian dance: basic Profession Actor, Speaker, Young actor Singing Song: basic folk song: basic Vita Lata S Singh by www.castupload.com — As of: 2021-05-16 Page 1 of 4 Pitch Alto Other licenses Motorbike test certificate Professional background Actor* Originally from Delhi, India where I found my foundation in street theatre during college. Currently lives in Mumbai. Will travel. Since 2015, I've been made to jump existential hoops by incredible mentors and theatre directors from France, Poland, UK, Portugal, -

Clare M. Wilkinson-Weber

Clare M. Wilkinson-Weber TAILORING EXPECTATIONS How film costumes become the audience’s clothes ‘Bollywood’ film costume has inspired clothing trends for many years. Female consumers have managed their relation to film costume through negotiations with their tailor as to how film outfits can be modified. These efforts have coincided with, and reinforced, a semiotic of female film costume where eroticized Indian clothing, and most forms of western clothing set the vamp apart from the heroine. Since the late 1980s, consumer capitalism in India has flourished, as have films that combine the display of material excess with conservative moral values. New film costume designers, well connected to the fashion industry, dress heroines in lavish Indian outfits and western clothes; what had previously symbolized the excessive and immoral expression of modernity has become an acceptable marker of global cosmopolitanism. Material scarcity made earlier excessive costume display difficult to achieve. The altered meaning of women’s costume in film corresponds with the availability of ready-to-wear clothing, and the desire and ability of costume designers to intervene in fashion retailing. Most recently, as the volume and diversity of commoditised clothing increases, designers find that sartorial choices ‘‘on the street’’ can inspire them, as they in turn continue to shape consumer choice. Introduction Film’s ability to stimulate consumption (responding to, and further stimulating certain kinds of commodity production) has been amply explored in the case of Hollywood (Eckert, 1990; Stacey, 1994). That the pleasures associated with film going have influenced consumption in India is also true; the impact of film on various fashion trends is recognized by scholars (Dwyer and Patel, 2002, pp. -

EXIGENCY of INDIAN CINEMA in NIGERIA Kaveri Devi MISHRA

Annals of the Academy of Romanian Scientists Series on Philosophy, Psychology, Theology and Journalism 80 Volume 9, Number 1–2/2017 ISSN 2067 – 113x A LOVE STORY OF FANTASY AND FASCINATION: EXIGENCY OF INDIAN CINEMA IN NIGERIA Kaveri Devi MISHRA Abstract. The prevalence of Indian cinema in Nigeria has been very interesting since early 1950s. The first Indian movie introduced in Nigeria was “Mother India”, which was a blockbuster across Asia, Africa, central Asia and India. It became one of the most popular films among the Nigerians. Majority of the people were able to relate this movie along story line. It was largely appreciated and well received across all age groups. There has been a lot of similarity of attitudes within Indian and Nigerian who were enjoying freedom after the oppression and struggle against colonialism. During 1970’s Indian cinema brought in a new genre portraying joy and happiness. This genre of movies appeared with vibrant and bold colors, singing, dancing sharing family bond was a big hit in Nigeria. This paper examines the journey of Indian Cinema in Nigeria instituting love and fantasy. It also traces the success of cultural bonding between two countries disseminating strong cultural exchanges thereof. Keywords: Indian cinema, Bollywood, Nigeria. Introduction: Backdrop of Indian Cinema Indian Cinema (Bollywood) is one of the most vibrant and entertaining industries on earth. In 1896 the Lumière brothers, introduced the art of cinema in India by setting up the industry with the screening of few short films for limited audience in Bombay (present Mumbai). The turning point for Indian Cinema came into being in 1913 when Dada Saheb Phalke considered as the father of Indian Cinema. -

Delhi Sultanate Pdf Download Delhi Sultanate Notes PDF Download |

delhi sultanate pdf download Delhi Sultanate Notes PDF Download | Delhi Sultanate Notes PDF Download - Delhi Sultanate Chapterwise and Typewise Notes Delhi Sultanate Delhi Sultanate notes PDF in Hindi Delhi Sultanate Book PDF, Delhi Sultanate handwritten Notes PDF Delhi Sultanate Chapterwise and Typewise Solved Paper class notes PDF Delhi Sultanate Notes Book PDF Delhi Sultanate – Download Social Studies Notes Free PDF For REET /UTET Exam. Social Studies is an important section for REET, MPTET , State TET, and other teaching exams as well. Social studies is the main subject in the REET, exam Paper II. In REET, UTET Exam, the Social Studies section comprises a total 60 questions of 60 marks, in which 40 questions come from the content section i.e. History, Geography and Political Science and the rest 20 questions from Social Studies Pedagogy section. At least 10-15 questions are asked from the History section in the REET, UTET Social studies section. Here we are providing important notes related to the Delhi Sultanate. Delhi Sultanate. The period from 1206 to 1526 in India history is known as Sultanate period. Slave Dynasty. In 1206 Qutubuddin Aibak made India free of Ghazni’s control. Rulers who ruled over India and conquered new territories during the period 1206-1290 AD. are known as belonging to Slave dynasty. Qutubuddin Aibak. He came from the region of Turkistan and he was a slave of Mohammad Ghori. He ruled as a Sultan from 1206 to 1210. While playing Polo, he fell from the horse and died in 1210. Aram Shah. After Aibak’s death, his son Aram Shah was enthroned at Lahore. -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

Chup Chup Ke Tamil Movie Free Download in Hd

Chup Chup Ke Tamil Movie Free Download In Hd 1 / 4 Chup Chup Ke Tamil Movie Free Download In Hd 2 / 4 3 / 4 …Mrs Rowdy Full Movie kutty movie collection 2016 ni tamil movie tnhits tamil ... arivu hd movie download tamilyogi online video ganduworld movie passport ... Saand Ki Aankh (2019) Hindi Full Movie Watch Online Free *Rip File* Saand Ki .... Story of movie Chup Chup Ke : Chup Chup Ke is a 2006 Bollywood film directed by Priyadarshan. The film has Shahid Kapoor and Kareena Kapoor in their third .... Chup Chup Ke Indian Hindi, Lyrics, Bollywood, Indian Movies, Songs, Movie .... Sarabham 2014 Tamil Full Movie Watch Online Free | Download Free Hindi Movies ... Fanaa (2006) Full Movie Watch Online HD Free Download | Flims Club Old .... Chup Chup Ke ... Watch all you want for free. TRY 30 ... Available to download. Genres. Indian Movies, Hindi-Language Movies, Bollywood Movies, Comedies, .... Chup Chup Ke Full movie online free 123movies BluRay 720p Online. ... Synopsis Chup Chup Ke 2006 Full Movie Download HD 720p, Chup Chup Ke 2006 .... Video: Watch Chalti Ka Naam Gaadi the Full Movie ... Chalti Ka Naam Gaadi {HD} - Bollywood Comedy Movie - Kishore Kumar .... The funny Tamil boy Amma Pakoda's act is an over-the-top comedy scene. .... Chupke Chupke, directed by Hrishikesh Mukherjee is a classic ...... Also Chup Chup ke missing.. Sign up for Mobile Passport which enables U.S. citizens and Canadian visitors to save time ... Free WiFi. Check your email, take care of business, or catch up with friends on social media. There's free wifi available throughout the terminal. -

MAX Security Report [email protected] +44 203 540 0434

MAX Security Report [email protected] +44 203 540 0434 Protest India Tactical: Release of controversial film on 23 January 25 expected to trigger nationwide JAN protests by Rajput community; maintain 12:30 UTC vigilance Please be advised • According to reports from January 23 quoting their leader, the Rajput activist Karni Sena organization will hold protests nationwide on January 25 against the release of a controversial Bollywood film. The group believes that the film presents the Rajput community in a negative light, and their leadership has pledged that “if screening of the film is not stopped, members of our community will not stop from demolishing screens in theaters”. • Intermittent protests against the film occurred across Gurgaon, Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh on January 22-23, as protesters blocked roads and demonstrated outside cinema halls. Reports also indicate vandalism of a mall in Gurgaon on January 22 by suspected Karni Sena activists, with the organization denying any involvement and attributing the attack to mischievous elements. • On January 18, the Supreme Court ruled that the states of Madhya Pradesh, Haryana, Rajasthan, and Gujarat must allow the unimpeded release of the film. The same day, suspected Karni Sena activists allegedly attacked a cinema hall in Bihar, and the Hindu right-wing Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and allied Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) organizations extended support for a ban on the movie. • Karni Sena supporters gathered outside the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) office in Mumbai on January 12, with 100 activists detained by police personnel shortly after. The organization held its largest protest march against the film in Surat, Gujarat on November 12 2017, page 1 / 4 which reportedly drew participation in excess of 100,000. -

Responses to 100 Best Acts Post-2009-10-11 (For Reference)

Bobbytalkscinema.Com Responses/ Comments on “100 Best Performances of Hindi Cinema” in the year 2009-10-11. submitted on 13 October 2009 bollywooddeewana bollywooddeewana.blogspot.com/ I can't help but feel you left out some important people, how about Manoj Kumar in Upkar or Shaheed (i haven't seen that) but he always made strong nationalistic movies rather than Sunny in Deol in Damini Meenakshi Sheshadri's performance in that film was great too, such a pity she didn't even earn a filmfare nomination for her performance, its said to be the reason on why she quit acting Also you left out Shammi Kappor (Junglee, Teesri MANZIL ETC), shammi oozed total energy and is one of my favourite actors from 60's bollywood Rati Agnihotri in Ek duuje ke Liye Mala Sinha in Aankhen Suchitra Sen in Aandhi Sanjeev Kumar in Aandhi Ashok Kumar in Mahal Mumtaz in Khilona Reena Roy in Nagin/aasha Sharmila in Aradhana Rajendra Kuamr in Kanoon Time wouldn't permit me to list all the other memorable ones, which is why i can never make a list like this bobbysing submitted on 13 October 2009 Hi, As I mentioned in my post, you are right that I may have missed out many important acts. And yes, I admit that out of the many names mentioned, some of them surely deserve a place among the best. So I have made some changes in the list as per your valuable suggestion. Manoj Kumar in Shaheed (Now Inlcuded in the Main 100) Meenakshi Sheshadri in Damini (Now Included in the Main 100) Shammi Kapoor in Teesri Manzil (Now Included in the Main 100) Sanjeev Kumar in Aandhi (Now Included in Worth Mentioning Performances) Sharmila Togore in Aradhana (Now Included in Worth Mentioning Performances) Sunny Deol in Damini (Shifted to More Worth Mentioning Performances) Mehmood in Pyar Kiye Ja (Shifted to More Worth Mentioning Performances) Nagarjun in Shiva (Shifted to More Worth Mentioning Performances) I hope you will approve the changes made as per your suggestions.