Why the Long Face? Comparative Shape Analysis of Miniature, Pony, and Other Horse Skulls Reveals Changes in Ontogenetic Growth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Horse Breeds 1 List of Horse Breeds

List of horse breeds 1 List of horse breeds This page is a list of horse and pony breeds, and also includes terms used to describe types of horse that are not breeds but are commonly mistaken for breeds. While there is no scientifically accepted definition of the term "breed,"[1] a breed is defined generally as having distinct true-breeding characteristics over a number of generations; its members may be called "purebred". In most cases, bloodlines of horse breeds are recorded with a breed registry. However, in horses, the concept is somewhat flexible, as open stud books are created for developing horse breeds that are not yet fully true-breeding. Registries also are considered the authority as to whether a given breed is listed as Light or saddle horse breeds a "horse" or a "pony". There are also a number of "color breed", sport horse, and gaited horse registries for horses with various phenotypes or other traits, which admit any animal fitting a given set of physical characteristics, even if there is little or no evidence of the trait being a true-breeding characteristic. Other recording entities or specialty organizations may recognize horses from multiple breeds, thus, for the purposes of this article, such animals are classified as a "type" rather than a "breed". The breeds and types listed here are those that already have a Wikipedia article. For a more extensive list, see the List of all horse breeds in DAD-IS. Heavy or draft horse breeds For additional information, see horse breed, horse breeding and the individual articles listed below. -

Electronic Supplementary Material - Appendices

1 Electronic Supplementary Material - Appendices 2 Appendix 1. Full breed list, listed alphabetically. Breeds searched (* denotes those identified with inherited disorders) # Breed # Breed # Breed # Breed 1 Ab Abyssinian 31 BF Black Forest 61 Dul Dülmen Pony 91 HP Highland Pony* 2 Ak Akhal Teke 32 Boe Boer 62 DD Dutch Draft 92 Hok Hokkaido 3 Al Albanian 33 Bre Breton* 63 DW Dutch Warmblood 93 Hol Holsteiner* 4 Alt Altai 34 Buc Buckskin 64 EB East Bulgarian 94 Huc Hucul 5 ACD American Cream Draft 35 Bud Budyonny 65 Egy Egyptian 95 HW Hungarian Warmblood 6 ACW American Creme and White 36 By Byelorussian Harness 66 EP Eriskay Pony 96 Ice Icelandic* 7 AWP American Walking Pony 37 Cam Camargue* 67 EN Estonian Native 97 Io Iomud 8 And Andalusian* 38 Camp Campolina 68 ExP Exmoor Pony 98 ID Irish Draught 9 Anv Andravida 39 Can Canadian 69 Fae Faeroes Pony 99 Jin Jinzhou 10 A-K Anglo-Kabarda 40 Car Carthusian 70 Fa Falabella* 100 Jut Jutland 11 Ap Appaloosa* 41 Cas Caspian 71 FP Fell Pony* 101 Kab Kabarda 12 Arp Araappaloosa 42 Cay Cayuse 72 Fin Finnhorse* 102 Kar Karabair 13 A Arabian / Arab* 43 Ch Cheju 73 Fl Fleuve 103 Kara Karabakh 14 Ard Ardennes 44 CC Chilean Corralero 74 Fo Fouta 104 Kaz Kazakh 15 AC Argentine Criollo 45 CP Chincoteague Pony 75 Fr Frederiksborg 105 KPB Kerry Bog Pony 16 Ast Asturian 46 CB Cleveland Bay 76 Fb Freiberger* 106 KM Kiger Mustang 17 AB Australian Brumby 47 Cly Clydesdale* 77 FS French Saddlebred 107 KP Kirdi Pony 18 ASH Australian Stock Horse 48 CN Cob Normand* 78 FT French Trotter 108 KF Kisber Felver 19 Az Azteca -

Estudio Comparativo Del Borde Dorsal Del Cuello En

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Portal de Revistas Científicas Complutenses ISSN: 1988‐2688 http://www.ucm.es/BUCM/revistasBUC/portal/modulos.php?name=Revistas2&id=RCCV&col=1 http://dx.doi.org/10.5209/rev_RCCV.2014.v8.n2.47161 Revista Complutense de Ciencias Veterinarias 2014 8(2):49-60 ESTUDIO COMPARATIVO DEL BORDE DORSAL DEL CUELLO EN EQUINOS MINIATURA COMPARATIVE STUDY OF DORSAL NECK IN EQUINE MINIATURE Abelardo Morales Briceño, Aniceto Méndez Sánchez, José Pérez Arévalo. ¹Departamento de Anatomía y Anatomía Patológica Comparadas, Edificio de Sanidad Animal, Campus de Rabanales Ctra. de Madrid km 396, 14071, Córdoba Universidad de Córdoba, España. Email: [email protected] RESUMEN Se plantea como objetivo un estudio comparativo del borde dorsal del cuello en equinos miniatura. Fueron estudiados un total de 125equinos miniatura de razas Falabella, MiniatureHorse, Pony Shetland, burro miniatura y enano (45 machos castrados y 80hembras), con edades comprendidas entre 2-20 años, sometidos a ejercicio de baja intensidad y diferentes condiciones de manejo y alimentación. Se realizó un estudio morfológico considerando la condición corporal, siguiendo el protocolo de adiposidad para la evaluación del borde dorsal del cuello descrito para equinos. El peso fue calculado empleando el sistema de ecuaciones KER descrito para caballos miniatura. Se realizó una estadística descriptiva a las medidas morfométricas del cuello y posteriormente se realizó un análisis de varianza (ANOVA). El estudio morfológico en evidenció una Puntuación 1.- 44% (55/125), Puntuación 2.- 32% (40/125), Puntuación 3.- 19% (24/125), Puntuación 4.- 5% (6/125). -

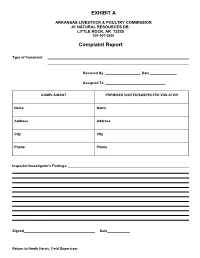

Complaint Report

EXHIBIT A ARKANSAS LIVESTOCK & POULTRY COMMISSION #1 NATURAL RESOURCES DR. LITTLE ROCK, AR 72205 501-907-2400 Complaint Report Type of Complaint Received By Date Assigned To COMPLAINANT PREMISES VISITED/SUSPECTED VIOLATOR Name Name Address Address City City Phone Phone Inspector/Investigator's Findings: Signed Date Return to Heath Harris, Field Supervisor DP-7/DP-46 SPECIAL MATERIALS & MARKETPLACE SAMPLE REPORT ARKANSAS STATE PLANT BOARD Pesticide Division #1 Natural Resources Drive Little Rock, Arkansas 72205 Insp. # Case # Lab # DATE: Sampled: Received: Reported: Sampled At Address GPS Coordinates: N W This block to be used for Marketplace Samples only Manufacturer Address City/State/Zip Brand Name: EPA Reg. #: EPA Est. #: Lot #: Container Type: # on Hand Wt./Size #Sampled Circle appropriate description: [Non-Slurry Liquid] [Slurry Liquid] [Dust] [Granular] [Other] Other Sample Soil Vegetation (describe) Description: (Place check in Water Clothing (describe) appropriate square) Use Dilution Other (describe) Formulation Dilution Rate as mixed Analysis Requested: (Use common pesticide name) Guarantee in Tank (if use dilution) Chain of Custody Date Received by (Received for Lab) Inspector Name Inspector (Print) Signature Check box if Dealer desires copy of completed analysis 9 ARKANSAS LIVESTOCK AND POULTRY COMMISSION #1 Natural Resources Drive Little Rock, Arkansas 72205 (501) 225-1598 REPORT ON FLEA MARKETS OR SALES CHECKED Poultry to be tested for pullorum typhoid are: exotic chickens, upland birds (chickens, pheasants, pea fowl, and backyard chickens). Must be identified with a leg band, wing band, or tattoo. Exemptions are those from a certified free NPIP flock or 90-day certificate test for pullorum typhoid. Water fowl need not test for pullorum typhoid unless they originate from out of state. -

This Is a Cross-Reference List for Entering Your Horses at NAN. It Will

This is a cross-reference list for entering your horses at NAN. It will tell you how a breed is classified for NAN so that you can easily find the correct division in which to show your horse. If your breed is designated "other pure," with no division indicated, the NAN committee will use body type and suitability to determine in what division it belongs. Note: For the purposes of NAN, NAMHSA considers breeds that routinely fall at 14.2 hands high or less to be ponies. Stock Breeds American White Horse/Creme Horse (United States) American Mustang (not Spanish) Appaloosa (United States) Appendix Quarter Horse (United States) Australian Stock Horse (Australia) Australian Brumby (Australia) Bashkir Curly (United States, Other) Paint (United States) Quarter Horse (United States) Light Breeds Abyssinian (Ethiopia) Andravida (Greece) Arabian (Arabian Peninsula) Barb (not Spanish) Bulichi (Pakistan) Calabrese (Italy) Canadian Horse (Canada) Djerma (Niger/West Africa) Dongola (West Africa) Hirzai (Pakistan) Iomud (Turkmenistan) Karabair (Uzbekistan) Kathiawari (India) Maremmano (Italy) Marwari (India) Morgan (United States) Moroccan Barb (North Africa) Murghese (Italy) Persian Arabian (Iran) Qatgani (Afghanistan) San Fratello (Italy) Turkoman (Turkmenistan) Unmol (Punjab States/India) Ventasso (Italy) Gaited Breeds Aegidienberger (Germany) American Saddlebred (United States) Boer (aka Boerperd) (South Africa) Deliboz (Azerbaijan) Kentucky Saddle Horse (United States) McCurdy Plantation Horse (United States) Missouri Fox Trotter (United States) -

Horse Breeds - Volume 2

Horse breeds - Volume 2 A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton Contents Articles Danish Warmblood 1 Danube Delta horse 3 Dølehest 4 Dutch harness horse 7 Dutch Heavy Draft 10 Dutch Warmblood 12 East Bulgarian 15 Estonian Draft 16 Estonian horse 17 Falabella 19 Finnhorse 22 Fjord horse 42 Florida Cracker Horse 47 Fouta 50 Frederiksborg horse 51 Freiberger 53 French Trotter 55 Friesian cross 57 Friesian horse 59 Friesian Sporthorse 64 Furioso-North Star 66 Galiceno 68 Galician Pony 70 Gelderland horse 71 Georgian Grande Horse 74 Giara horse 76 Gidran 78 Groningen horse 79 Gypsy horse 82 Hackney Horse 94 Haflinger 97 Hanoverian horse 106 Heck horse 113 Heihe horse 115 Henson horse 116 Hirzai 117 Hispano-Bretón 118 Hispano-Árabe 119 Holsteiner horse 120 Hungarian Warmblood 129 Icelandic horse 130 Indian Half-Bred 136 Iomud 137 Irish Draught 138 Irish Sport Horse 141 Italian Heavy Draft 143 Italian Trotter 145 Jaca Navarra 146 Jutland horse 147 Kabarda horse 150 Kaimanawa horse 153 Karabair 156 Karabakh horse 158 Kathiawari 161 Kazakh horse 163 Kentucky Mountain Saddle Horse 165 Kiger Mustang 168 Kinsky horse 171 Kisber Felver 173 Kladruber 175 Knabstrupper 178 Konik 180 Kustanair 183 References Article Sources and Contributors 185 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 188 Article Licenses License 192 Danish Warmblood 1 Danish Warmblood Danish Warmblood Danish warmblood Alternative names Dansk Varmblod Country of origin Denmark Horse (Equus ferus caballus) The Danish Warmblood (Dansk Varmblod) is the modern sport horse breed of Denmark. Initially established in the mid-20th century, the breed was developed by crossing native Danish mares with elite stallions from established European bloodlines. -

Clicking Here

P a g e 1 | 14 All horses entering all classes MUST be registered or over stamped with the International Miniature Horse & Pony Society Ltd. Over stamping MUST be completed prior to the Judges show. To over stamp please visit the website and apply to the Registrar. For all details and forms to complete, visit Mrs V.J.Hampton www.imhps.com Mr P Matthews – Brown Mrs L McCormack Show Location Mrs J Davenport-Lister Onley Grounds Farm, Willoughby, Rugby, CV23 8AJ, United Kingdom Mrs V Huddleston Mr E Scofield Show Date & Start times Mr A Thomas-Chambers Saturday 25th September 2021 Ring 1: 8.30am | Ring 2: 8:00am | Ring 3: 9:30am Performance Organizers Sunday 26th September 2021 Mrs J Davenport-Lister Ring 1: 10.00 am | Ring 2: 9:00am Photographer Entry Information TBC Saturday entry fee: £12 per class Commentator Sunday entry fee: £10 per class Simon Richardson Early Bird Entries close 28th August 2021 Official entries close: 11th September 2021 Registrar Mel Williamson Tel: +44 (0)7787 644408 No Entries on the day - (Except 2021 graded horses entering classes 84-87) Email: [email protected] Address for Entries: Membership fees: Associate Single Membership: £15.00 Mandy Jones - Ty-Yn-Maes, Retford Road, Walesby, Notts, NG22 9PE Associate Family Membership: £25.00 Stabling Health Requirements Please contact the show ground directly: All horses must have documentation, endorsed by a Onley Grounds Equestrian Complex: Contact number: veterinarian, of an initial series of 2 intramuscular injections 01788 817724 for primary vaccination against equine influenza given no less than 21 days and no more than 92 days apart. -

NAN 2019 Breed Cross Reference List

This is a cross-reference list for entering your horses at NAN. It will tell you how a breed is classified for NAN so that you can easily find the correct division in which to show your horse. If your breed is designated "other pure," with no division indicated, the NAN committee will use body type and suitability to determine in what division it belongs. Note: For the purposes of NAN, NAMHSA considers breeds that routinely fall at 14.2 hands high or less to be ponies. Stock Breeds American White Horse/Creme Horse (United States) American Mustang (not Spanish) Appaloosa (United States) Appendix Quarter Horse (United States) Australian Stock Horse (Australia) Australian Brumby (Australia) Bashkir Curly (United States, Other) Paint (United States) Quarter Horse (United States) Light Breeds Abyssinian (Ethiopia) American Saddlebred (United States) Andravida (Greece) Arabian (Arabian Peninsula) Barb (not Spanish) Bulichi (Pakistan) Calabrese (Italy) Djerma (Niger/West Africa) Dongola (West Africa) Hirzai (Pakistan) Iomud (Turkmenistan) Karabair (Uzbekistan) Kathiawari (India) Maremmano (Italy) Marwari (India) Morgan (United States) Moroccan Barb (North Africa) Murghese (Italy) Persian Arabian (Iran) Qatgani (Afghanistan) San Fratello (Italy) Turkoman (Turkmenistan) Unmol (Punjab States/India) Ventasso (Italy) Gaited Breeds Aegidienberger (Germany) Boer (aka Boerperd) (South Africa) Deliboz (Azerbaijan) Kentucky Saddle Horse (United States) McCurdy Plantation Horse (United States) Missouri Fox Trotter (United States) North American Single-Footer -

Chondrodysplasia-Like Dwarfism in the Miniature Horse

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Veterinary Science Veterinary Science 2013 Chondrodysplasia-Like Dwarfism in the Miniature Horse John E. Eberth University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Eberth, John E., "Chondrodysplasia-Like Dwarfism in the Miniature Horse" (2013). Theses and Dissertations--Veterinary Science. 11. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gluck_etds/11 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Veterinary Science at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Veterinary Science by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained and attached hereto needed written permission statements(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine). I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless a preapproved embargo applies. I retain all other ownership rights to the copyright of my work. -

Apuntes De Clases Sobre El Caballo (Documento De Estudio Para Estudiantes De Ingeniería En Zootecnia)

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AGRARIA FACULTAD DE CIENCIA ANIMAL “Por un Desarrollo Agrario Integral y Sostenible” ZZ♀♀♂♂TTEECCNNIIAA EEQQUUIINNA:A Apuntes de clases sobre el caballo (Documento de estudio para estudiantes de Ingeniería en Zootecnia) Ing. Alcides Arsenio Sáenz García MSc. Managua, Nicaragua Junio, 2008 Z♀♂tecnia Equina: Apuntes de clases sobre el Caballo Universidad Nacional Agraria PRESENTACIÓN Estos apuntes de clases han sido preparados para la asignatura de Zootecnia Equina que se imparte en el sexto semestre de la carrera Ingeniería en Zootecnia dictado por el Departamento Sistemas Integrales de Producción Animal (SIPA) de la Facultad de Ciencia Animal. Gran parte del contenido está basado en anotaciones de clases y de algunos artículos técnicos de páginas electrónicas de Internet. Si el lector encuentra en estos apuntes alguna información útil se la debo a las personas experimentadas en la cría caballar y que han escrito e investigado sobre la producción equina, por los errores, que con seguridad existen, asumo total responsabilidad. El contenido de estos apuntes debe cubrir la mayor parte de los temas a tratar en la asignatura, pero en ningún caso reemplazar a un buen texto de estudio. La ganadería equina en Nicaragua se inició desde la época de la conquista española, cuando los colonizadores introdujeron los primeros ejemplares. Las primeras yeguadas traídas en ese entonces correspondían al tipo berberisco español, animales de aptitud cárnica. Estos se abandonaron a la buena de Dios, sobreviviendo los más aptos y los que toleraron las condiciones de nuestro medio, dando lugar así a la formación del caballo criollo o cholenco, animal con muy baja capacidad productiva. -

Registration 2021

International Miniature Horse & Pony Society www.imhps.com e-mail: [email protected] APPLICATION FOR HORSE / DONKEY PASSPORT o PASSPORT o EXPRESS PASSPORT ARE YOU AN IMHPS MEMBER YES / NO Please check current fees at www.imhps.com/fees.html and return form to the Registrar (Tick ü appropriate category) o International Miniature Horses not exceeding 34” (86.5cm) o Midi horses and ponies exceeding 34” (86.5cm) but not exceeding 42” (106.5cm) 100% pure-bred Falabella horses which will have to be registered with The Falabella Studbook (www.thefalabellastudbook.com) and be o subject to their regulations. IMHPS do not hold the official studbook for this breed and therefore the passport issued will be for an International Miniature Horse, but will have complete breeding records inserted from The Falabella Studbook. o Latin American blend horses of less than 100% Falabella bloodlines Passport will be issued as International Miniature Horse o American Miniature horses pure-bred o American Miniature horses part-bred IMHPS do not hold the official studbook for this breed and therefore the passport issued will be for an International Miniature Horse The following will be ID only passports; however breeding details, where available, will be provided in non-statutory pages at the back of the passport o Donkeys or mules not exceeding 36” (91.5cm) o Donkeys or mules exceeding 36” (91.5cm) o Horse or pony (any height) Name ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..………. Registered Prefix ………………………………………………………..Date of foaling …………………………………………………….. Must be registered with British Central Prefix Registry (DD/MM/YYYY). Colour ………………………………………………………..Sex …………………………………………………….. Mare, gelding, stallion, colt, filly European Height ………………………………………………………..Worldwide Height ………………………………………………………. -

The Management of Miniature Horses at Pasture in New Zealand

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. The management of Miniature horses at pasture in New Zealand A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy (without specialisation) at Massey University, Manawatῡ campus, New Zealand Sheen Yee Goh 2020 Abstract Studies on the demographics, feeding management and health care practices of Miniature horses in New Zealand have yet to be conducted. Thus, the aim of this study is to describe the demographics, feeding management and health care practices of Miniature horses in New Zealand. To achieve the aim of this study, an online survey was conducted using the Qualtrics Survey Software. There were 232 valid responses from respondents who kept 1,183 Miniature horses, representing approximately one third of the New Zealand Miniature horse population. Miniature horses were kept for leisure and companionship (56%), competition (35%) and for breeding (7%). The median number of Miniature horses kept by owners for leisure and companionship was significantly lower (two horses) than those kept for competition (six horses) or for breeding (ten horses) (p<0.05). The majority (79%) of Miniature horses were kept at pasture on low (<1,000 kg DM/ha) to moderate (~2,000 kg DM/ha) pasture masses across seasons. Pasture access was more commonly restricted by respondents during spring (60%), summer (60%), and autumn (55%) than in winter (43%).