Dibble Sticks, Donkeys and Diesels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What You Need to Know About Mounting Radial Tires on Classic Vehicle Rims

What You Need to Know About Mounting Radial Tires on Classic Vehicle Rims Over the past 100 years, tires, and the wheels that support them, have gone through significant changes as a result of technical innovations in design, technology and materials. No single factor affects the handling and safety of a car’s ride more than the tire and the wheel it is mounted on and how the two work together as a unit. One nagging question that has been the subject of a lot of anecdotal evidence, speculation, and even more widespread rumor is whether rims designed for Bias ply tires can handle the stresses placed on them by Radial ply tires. And the answer is - it depends. It depends on how the rim was originally designed and built as well as whether the rim has few enough cycles on it, and how it has been driven. But most importantly it depends upon the construction of the tire and how it transmits the vehicle's load to where the rubber meets the road. In this paper, we want to educate you on the facts - not the wives tales or just plain bad information - about how Bias and Radial tires differ in working with the rim to provide a safe ride. Why is there a possible rim concern between Radial and Bias Tires? The fitting of radial tires, to wheels and rims originally designed for bias tires, is an application that may result in rim durability issues. Even same-sized bias and radial tires stress a rim differently, despite their nearly identical dimensions. -

MICHELIN® X® TWEEL® TURF™ the Airless Radial Tire™ & Wheel Assembly

MICHELIN® X® TWEEL® TURF™ The Airless Radial Tire™ & wheel assembly. Designed for use on zero turn radius mowers. ✓ NO MAINTENANCE ✓ NO COMPROMISE ✓ NO DOWNTIME MICHELIN® X® TWEEL® TURF™ No Maintenance – MICHELIN® X® TWEEL® TURF™ is one single unit, replacing the current tire/wheel/valve assembly. Once they are bolted on, there is no air pressure to maintain, and the common problem of unseated beads is completely eliminated. No Compromise – MICHELIN X TWEEL TURF has a consistent hub height which ensures the mower deck produces an even cut, while the full-width poly-resin spokes provide excellent lateral stability for outstanding side hill performance. The unique design of the spokes helps dampen the ride for enhanced operator comfort, even when navigating over curbs and other bumps. High performance compounds and an effi cient contact patch offer a long wear life that is two to three times that of a pneumatic tire at equal tread depth. No Downtime – MICHELIN X TWEEL TURF performs like a pneumatic tire, but without the risk and costly downtime associated with fl at tires and unseated beads. Zero degree belts and proprietary design provide great lateral stiffness, while resisting damage Multi-directional and absorbing impacts. tread pattern is optimized to provide excellent side hill stability and prevent turf High strength, damage. poly-resin spokes carry the load and absorb impacts, while damping the ride and providing a unique energy transfer that Michelin’s reduces “bounce.” proprietary Comp10 Cable™ forms a semi-rigid “shear beam”, Heavy gauge and allows the steel with 4 bolt load to hang hub pattern fi ts from the top. -

MICHELIN® X® TWEEL Warranty Overview

MICHELIN® TWEEL® Airless radial tire Warranty Guide Contents MICHELIN® Tweel® Tire Warranty Overview ............................................................................. 3–4 Common Warranty Specifi cations ...............................................................................................5 Parts of a Tweel® Airless Radial Tire .............................................................................................5 Examination Tools .......................................................................................................................6 MICHELIN® X® TWEEL® SSL AIRLESS RADIAL TIRES Technical Specifi cations: MICHELIN® X® Tweel® SSL Tires .............................................................6 MICHELIN® X® Tweel® SSL Tire Torque Specs and Retreading .......................................................7 Tweel® SSL Tire Warranty vs. Wear Guide ..............................................................................8–12 MICHELIN® X® TWEEL® TURF AIRLESS RADIAL TIRES Technical Specifi cations: MICHELIN® X® Tweel® Turf Tires ...........................................................13 Tweel® Turf Tire Proper Installation Instructions ..........................................................................13 Tweel® Turf Tire Warranty vs. Wear Guide ........................................................................... 14–17 MICHELIN® X® TWEEL® CASTERS Technical Specifi cations: MICHELIN® X® Tweel® Casters..............................................................17 Tweel® Caster Warranty -

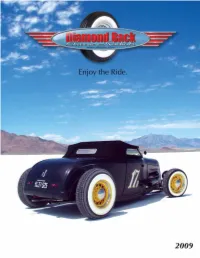

The World's Most Beautiful And... Best Performing Custom Designed Tires

WelcomeWelcome ToTo TheThe World’sWorld’s MostMost BeautifulBeautiful and...and... BestBest PerformingPerforming CustomCustom DesignedDesigned TiresTires Bill Chapman Founder Diamond Back Classics I know what you are thinking! The tires on Bill’s Corvette are not correct. It’s not a show car-it is for my enjoyment. That’s the beauty of Diamond Back-you can get what’s period correct or you can get what you like. Custom whitewalls are not a problem. I offer many correct styles for the 60’s and 70’s cars or if you want something special, just let us know. My 2009 catalog features 16 product lines from 13” to 22” and anything in between. That’s more product than all the competitor’s combined. I’m also introducing two new top end product lines-the Diamond Back MX and the Diamond Back III. Both are built in North America by Michelin, the world’s most recognized tire manufacturer. If you’re going to spend over $200 per tire why not get the very best? Prices on the rest of my products will have a small increase and some will remain unchanged. Check out my warranty. It is the most solid, easy to understand warranty in the industry. My new extended warranty for $4.75 per tire is a smart move to protect your investment. As the year of the Great Recession begins, my goal remains unchanged-build the best looking, best performing product at a fair price. Thanks for all of your support! Confused and concerned about using radial tires on older rims? Get the facts .. -

Correct Tires for 1953-82 Corvettes

FULL OF HOT AIR Correct tires for 1953-82 Corvettes he subject of correct tires for your vintage Corvette can sometimes be an overwhelming subject. Finding an original NOS (New Old Stock) tire or, T heaven forbid, a full set of four plus a spare for some early Corvettes can be next to impossible, even with the internet and the vast number of parts ads in many ma- jor magazines. There are still some original tires out there, with these tires usually be- ing found in old tire warehouses or stumbled upon when a large car parts collection is liq- uidated. In either case, the sometimes-long search can be quite frustrating. The fact of the matter is that the types and sizes of tires that were used on Corvettes from 1953 through 1982 are quite varied in BF Goodrich Wide Whitewall construction and size. In addition, the us- the originals. It should be mentioned here age was somewhat varied from year to year that the DOT (Department of Transportation) dependent on the options that could be or- markings that are required to be on all repro- dered on the car. It should be stated here duction tires were not in use when the origi- that most Corvettes driven today do not car- nal tires were manufactured for most early ry the original tires they were delivered with to Corvettes. This is one quick way to discern if the dealership. Tire technology has changed the tire you are about to buy from an individ- dramatically over the last 40+ years and ual or dealer is an original or a new reproduc- most Corvette owners who drive their car on tion. -

Hydroplaning Analysis for Tire Rolling Over Water Film with Various Thicknesses Using the LS-DYNA Fluid-Structure Interactive Scheme

Copyright © 2009 Tech Science Press CMC, vol.11, no.1, pp.33-58, 2009 Hydroplaning Analysis for Tire Rolling over Water Film with Various Thicknesses Using the LS-DYNA Fluid-Structure Interactive Scheme Syh-Tsang Jenq1;2 and Yuen-Sheng Chiu2 Abstract: Current work studies the transient hydroplaning behavior of 200 kPa inflated pneumatic radial tires with various types of tread patterns. Tires were nu- merically loaded with a quarter car weight of 4 kN, and then accelerated from rest rolling over a water film with a thickness of 5, 10 and 15 mm on top of a flat pavement. Tire structure is composed of outer rubber tread and inner fiber rein- forcing composite layers. The Mooney-Rivlin constitutive law and the classical laminated theory (CLT) were, respectively, used to describe the mechanical be- havior of rubber material and composite reinforcing layers. The tire hydroplaning phenomenon was analyzed by the commercial finite element code - LS-DYNA. The Arbitrary Lagrangian & Eulerian (ALE) formulation was adopted to depict the fluid-structure interaction (FSI) behavior. Three different tire tread patterns, i.e. the smooth (blank) tread pattern and the 9 and 18 mm wide longitudinally-grooved tread patterns, were constructed to perform the current transient hydroplaning anal- ysis. Simulated dynamic normal contact force and hydroplaning velocity of tire with a prescribed smooth tread pattern were obtained. The computed results were in good agreement with the numerical and test results given by Okano, et al. (2001) for tire running over 10 mm thick water fluid film. In addition, dynamic contact force of a smooth tread pattern tire rolling on a dry flat pavement was also found to be close to the result reported by Nakajima, et al. -

Aircraft Tire Data

Aircraft tire Engineering Data Introduction Michelin manufactures a wide variety of sizes and types of tires to the exacting standards of the aircraft industry. The information included in this Data Book has been put together as an engineering and technical reference to support the users of Michelin tires. The data is, to the best of our knowledge, accurate and complete at the time of publication. To be as useful a reference tool as possible, we have chosen to include data on as many industry tire sizes as possible. Particular sizes may not be currently available from Michelin. It is advised that all critical data be verified with your Michelin representative prior to making final tire selections. The data contained herein should be used in conjunction with the various standards ; T&RA1, ETRTO2, MIL-PRF- 50413, AIR 8505 - A4 or with the airframer specifications or military design drawings. For those instances where a contradiction exists between T&RA and ETRTO, the T&RA standard has been referenced. In some cases, a tire is used for both civil and military applications. In most cases they follow the same standard. Where they do not, data for both tires are listed and identified. The aircraft application information provided in the tables is based on the most current information supplied by airframe manufacturers and/or contained in published documents. It is intended for use as general reference only. Your requirements may vary depending on the actual configuration of your aircraft. Accordingly, inquiries regarding specific models of aircraft should be directed to the applicable airframe manufacturer. -

Analysis of Influencing Factors of Tire Hydroplaning

International Journal of Engineering Innovation & Research Volume 10, Issue 2, ISSN: 2277 – 5668 Analysis of Influencing Factors of Tire Hydroplaning Chengwei Xu1, Qingzhi Ma2, Jing Wang2, Ruifeng Sun3, Mengyu Xie1 and Congzhen Liu1* 1 School of Transportation and Vehicle Engineering, Shandong University of Technology, Shandong, Zibo, Zhangdian, 255049, China. 2 Technology Center, Shandong Tangjun Ouling Automobile Manufacture Co., Ltd., Shandong, Zibo, Zichuan, 255000, China. 3 Forestry College, Shandong Agricultural University, Shandong, Taian, Taishan, 271018, China. Date of publication (dd/mm/yyyy): 05/04/2021 Abstract – In order to study the influencing factors of tire hydroplaning performance on wet roads, the 205/55 R16 radial tire is used as the research object, and the finite element method is used to simulate the hydroplaning process of the tire. First, the tire finite element model is established, and then the “tire-water-road” finite element model is established using the CEL method to study the influence of water film thickness, vehicle speed, vertical load and tire pressure on tire hydroplaning performance. The results show that the road contact force and road contact area decrease with the increase of water film thickness and speed, and increase with the increase of vertical load and tire pressure. Appropriately reducing the speed and increasing the inflating pressure are helpful to driving safely in rainy weather. Keywords – Tire Hydroplaning, Coupled Euler-Lagrange (CEL), Wet Road, Radial Tire. I. INTRODUCTION The performance of safe driving on wet roads is the basic requirement for tires. Studies have shown that [1- 3], about 20% of road accidents occur in wet weather conditions, and tire hydroplaning is the main cause of accidents. -

Experience the Performance Experience the Performance

WORLD CLASS TECHNOLOGY & QUALITY PRODUCT GUIDE EXPERIENCE THE PERFORMANCE EXPERIENCE THE PERFORMANCE EXPERIENCE THE PERFORMANCE 30 DAY TEST DRIVE . 4 SPORT CHAMPIRO SX2 | EXTREME PERFORMANCE SUMMER . 6 . CHAMPIRO HPY | MAX PERFORMANCE SUMMER . 8 AS CHAMPIRO UHP | ULTRA HIGH PERFORMANCE ALL-SEASON . 10. COMFORT MAXTOUR LX | GRAND TOURING & CUV ALL-SEASON . 12. MAXTOUR ALL SEASON | PASSENGER ALL-SEASON . 14 . SUV / PICKUP ADVENTURO HT | HIGHWAY ALL-SEASON . 16 . 3 ADVENTURO AT | ON / OFF ROAD ALL-TERRAIN . 18 . PRO MAXMILER PRO | COMMERCIAL VAN ALL-SEASON . 20 MAXMILER ST | TRAILER SERVICE . 22 . POSITIONING CHARTS . 24 DESIGNATIONS, LOAD INDEX & SPEED RATING . 25 WARRANTIES & ROADSIDE ASSISTANCE . 26 It’s your call. Test Drive EXPERIENCE THE PERFORMANCE 30 DAY TEST DRIVE UP TO 500 MILES OR 30 DAYS, WHICHEVER COMES FIRST. Buy a set of GT Radial tires and try them on your car or light truck. Experience the performance of GT Radial tires for yourself. If you’re not completely satisfied, just return them to the dealer where you bought them. Your GT Radial dealer will replace the tires or refund the purchase price—it’s your call. SATISFACTION Visit www.GTRadial-US.com/30daytestdrive for more information. GUARANTEED CHAMPIRO HPY CHAMPIRO UHPAS MAXTOUR LX MAXTOUR ALL SEASON ADVENTURO HT ADVENTURO AT3 EXTREME PERFORMANCE SUMMER 15 / 17 / 18 Inch Extreme Grip Dry Wet Handling Speed Rating: W 35 - 50 Series Champiro SX2 is for drivers who need higher levels of grip, traction, response and control in dry and wet conditions . With an extremely aggressive asymmetric tread design for increased cornering UTQG: 200 A A - 260 A A stability and high-grip silica compound that gives consistent performance, it is suitable for track days, spirited driving and normal street use . -

Tire Tread Depth and Wet Traction – a Review

A Crain Communications Event 1725 Merriman Road * Akron, Ohio 44313-9006 Phone: 330.836.9180 * Fax: 330.836.1005 * www.rubbernews.com ITEC 2014 Paper W-4 All papers owned and copyrighted by Crain Communications, Inc. Reprint only with permission Tire Tread Depth and Wet Traction – A Review W. Blythe William Blythe, Inc. Palo Alto, California Introduction The relationship of tire tread depth to wet traction has been a subject of technical research and discussion since at least the mid 1960s. Now, nearly 50 years on, these discussions continue, and disagreements regarding the importance of improving wet traction also continue. During this time, bias-ply tires have been replaced by radial construction and, in the USA, highway speeds have increased; miles driven have approximately tripled. This Paper reviews research that strongly suggests an increase in minimum tire tread depth requirements would significantly and positively affect highway safety. Historical Data Radial tire wet frictional performance is compared to bias-ply tire performance in Figure 1, taken from [1], a 1967 Paper. Since radial tires comprise almost all passenger car tires in use, any conclusions relating to tire performance based upon bias-ply tires probably no longer are valid. In these braking tests of fully-treaded tires, water depth was controlled at ¼ inch. As an example of increased highway speeds, posted speed limits of 70 mph on “Interstate System and non-interstate system routes” changed in the USA from zero miles so posted in 1994 to 40,897 miles in 2000. [2] 1 Figure 1 – Radial vs Bias Ply Tires Braking Coefficients, ¼ Inch Water Depth, 1967 Figure 2 shows the estimated total miles driven on all USA roads per year from 1971 through 2013. -

Development in Sidewall Reinforced Run-Flat Tire

Seoul 2000 FISITA World Automotive Congress F2000G427 June 12-15, 2000, Seoul, Korea Development in Sidewall Reinforced Run-Flat Tire Jin Kook Kim*, Yang Nam Lim, Nam-Jeon Kim Kumho Tire R&D Center , Kumho Industrial Co., Ltd. 555,Sochon-dong, Kwangsan-gu, Kwangju, 506-040, Korea Despite the disadvantages in aspects of ride comfort due to the thick sidewall, sidewall reinforced run-flat tires, compared to other types of run-flat tires, have more advantages in use of commercially available rim, easy assembly of tire and rim and manufacturing processibility. In this paper, the design concepts and problems encountered in the development of sidewall reinforced run-flat tires are studied. The condition of no internal air pressure under the vertical load induces the severe bending force on the sidewalls of the tire. To develop the sidewall reinforcing rubber compound and the sidewall construction to support this bending force efficiently are the core concerns for designing the sidewall reinforced run-flat tire. The bending force also causes a problem of bead unseating from the rim. In addition to that, another problem is how to solve the manufacturing process problems which come from thicker sidewall compared to the standard tires. Finite element method was widely used to understand the basic mechanism and to design the construction of the run-flat tire. Keywords: run-flat, tire, sidewall, tire which has reinforced sidewall to support vehicle INTRODUCTION weight Despite the disadvantages in aspects of ride comfort due Pneumatic tires appeared about 100 years ago. Only a to the thick sidewall, sidewall reinforced run-flat tires, few years were taken for pneumatic tires to replace the compared to other types of run-flat tires, have more wheel of a horse-drawn wagon which had been used in advantage in use of commercially available rim, easy many thousand years. -

Michelin® X® Tweel® Airless Radial Tire Fitment Guide February 13, 2021

Michelin® X® Tweel® Airless Radial Tire Fitment Guide February 13, 2021 Your Supplier of Choice gardnerinc.com ConteNts What is a Michelin ® X ® Tweel® Airless Radial Tire? MICHELIN® X® TWEEL TURF FOR ZERO-TURN RADIUS MOWERS No Maintenance GENERAL PRODUCT INFORMATION 2 The MICHELIN® X® TWEEL® airless radial tire is one single unit, replacing the current tire and wheel assembly. There is no need for complex mounting FITMENT DETAILS 3–20 equipment and once they are bolted on, there is no air pressure to maintain. No compromise MICHELIN® X® TWEEL UTV The unique energy transfer within the poly-resin spokes helps reduce the FOR ATVS AND UTVS “bounce” associated with pneumatic tires, while providing outstanding handling characteristics. GENERAL PRODUCT INFORMATION 21 No downtime (no flats!) ® FITMENT DETAILS 22–28 The TWEEL airless radial tire is designed to perform like a pneumatic tire, but without the inconvenience and downtime associated with fl at tires. MICHELIN® X® TWEEL SSL 2 FOR SKID STEER LOADERS GENERAL PRODUCT INFORMATION 29 FITMENT DETAILS 30–32 Use of incorrect mounting hardware can lead to separation of the TWEEL from the vehicle, loss of control, and serious injury or death Suggested fi tment information provided in this guide is based on available information at the time of publication. Manufacturer’s specifi cations are subject to change without notice. Page 1 Your Supplier of Choice gardnerinc.com MICHELIN® X® TWEEL® TURF (for zero-turn radius mowers) AVAILABLE IN SIZES TO FIT A WIDE RANGE OF MOWERS MOWERS MSPN CAI Description Size Center Color Max Load (lbs.) Wheel Offset (in.) Bolt Pattern Weight (lbs.) 01133 019985 X-Tweel Turf 18x8.5N10 Black 529 -0.4 4x4 in.