Asking Descriptive Questions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music & Entertainment Auction

Hugo Marsh Neil Thomas Plant (Director) Shuttleworth (Director) (Director) Music & Entertainment Auction 20th February 2018 at 10.00 For enquiries relating to the sale, Viewing: 19th February 2018 10:00 - 16:00 Please contact: Otherwise by Appointment Saleroom One, 81 Greenham Business Park, NEWBURY RG19 6HW Telephone: 01635 580595 Christopher David Martin David Howe Fax: 0871 714 6905 Proudfoot Music & Music & Email: [email protected] Mechanical Entertainment Entertainment www.specialauctionservices.com Music As per our Terms and Conditions and with particular reference to autograph material or works, it is imperative that potential buyers or their agents have inspected pieces that interest them to ensure satisfaction with the lot prior to the auction; the purchase will be made at their own risk. Special Auction Services will give indica- tions of provenance where stated by vendors. Subject to our normal Terms and Conditions, we cannot accept returns. Buyers Premium: 17.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 21% of the Hammer Price Internet Buyers Premium: 20.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 24.6% of the Hammer Price Historic Vocal & other Records 9. Music Hall records, fifty-two, by 16. Thirty-nine vocal records, 12- Askey (3), Wilkie Bard, Fred Barnes, Billy inch, by de Tura, Devries (3), Doloukhanova, 1. English Vocal records, sixty-three, Bennett (5), Byng (3), Harry Champion (4), Domingo, Dragoni (5), Dufranne, Eames (16 12-inch, by Buckman, Butt (11 - several Casey Kids (2), GH Chirgwin, (2), Clapham and inc IRCC20, IRCC24, AGSB60), Easton, Edvina, operatic), T Davies(6), Dawson (19), Deller, Dwyer, de Casalis, GH Elliot (3), Florrie Ford (6), Elmo, Endreze (6) (39, in T1) £40-60 Dearth (4), Dodds, Ellis, N Evans, Falkner, Fear, Harry Fay, Frankau, Will Fyfe (3), Alf Gordon, Ferrier, Florence, Furmidge, Fuller, Foster (63, Tommy Handley (5), Charles Hawtrey, Harry 17. -

Lots of Changes for Tour Championship East Lake Renovated; New Date; No Woods

« GEORGIAPGA.COM GOLFFOREGEORGIA.COM « SEPTEMBER 2008 Lots of changes for Tour Championship East Lake renovated; new date; no Woods By Mike Blum G R record 23-under 257. Only three of 30 E B N I ust as in the Presidential race, the word D players were over par for the week, with E V E T 2-over 282 tying for last place. change will be closely associated with S the 2008 PGA Tour Championship “When you give these players soft presented by Coca-Cola. greens, they’re going to shoot lights out,” J Burton says. “It will be a lot different this Other than returning to East Lake for the fifth straight year – the eighth time year with greens that are firm and fast.” overall – with a field of 30 top PGA Tour East Lake closed for play March 1 and pros, there will be a lot of changes for this will not re-open until Tour Championship month’s event, with the tournament sched - week. Players and spectators will notice uled for Sept. 25-28. some changes to the course, which will still Since last year’s tournament, the course play to a par of 70 for the tournament has undergone renovations, stemming but has been lengthened to just over from the problems East Lake’s bent grass 7,300 yards. greens encountered from last summer’s Perhaps the most dramatic change is the hot, dry weather. addition of a new tee on the picturesque East Lake’s putting surfaces have been par-3 sixth hole, one of the first in golf to converted to mini-verde, an ultra-dwarf feature an island green. -

Celebrations

Celebrations Alentejo Portalegre Islamic Festival “Al Mossassa” Start Date: 2021-10-01 End Date: 2021-10-03 Website: https://www.facebook.com/AlMossassaMarvao/ Contacts: Vila de Marvão, Portalegre The historic town of Marvão, in Alto Alentejo, will go back in time to evoke the time of its foundation by the warrior Ibn Maruam, in the ninth century, with an Islamic festival. Historical recreations with costumed extras, an Arab market, artisans working live, a military camp with weapons exhibition, games for children, knights in gun duels, exotic music and dance, acrobats, fire- breathers, snake charmers , bird of prey tamers and circus arts are some of the attractions. Centro de Portugal Tomar Festa dos Tabuleiros (Festival of the Trays) Date to be announced. Website: http://www.tabuleiros.org Contacts: Tomar The Festival of the Trays takes place every four years; the next one will take place in July 2023. Do not miss this unique event! The blessing of the trays, the street decorations, the quilts in the windows and the throwing of flowers over the procession of the trays carried by hundreds of young girls on their heads, is an unforgettable sight. The Procession of the Tabuleiros, heralded by pipers and fireworks, is led by the Banner of the Holy Ghost and the three Crowns of the Emperors and Kings. They are followed by the Banners and Crowns from all the parishes, and the girls carrying the trays. In the rear are the cartloads of bread, meat and wine, pulled by the symbolic sacrificial oxen, with golden horns and sashes. The girls who carry the trays have to wear long white dresses with a coloured sash across the chest. -

Martin V. PGA Tour, Inc., 984 F

No. 98-35309 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT ________________ CASEY MARTIN, Plaintiff-Appellee v. PGA TOUR, INC., Defendant-Appellant ___________________ ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF OREGON ___________________ BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE ___________________ BILL LANN LEE Acting Assistant Attorney General JESSICA DUNSAY SILVER THOMAS E. CHANDLER Attorneys Department of Justice P.O. Box 66078 Washington, D.C. 20035-6078 (202) 514-3728 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION ................... 1 INTEREST OF THE UNITED STATES ................. 1 STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES .................... 2 STATEMENT OF THE CASE ..................... 3 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ............ 11 ARGUMENT: I. THE GOLF COURSES ON WHICH THE PGA TOUR CONDUCTS ITS TOURNAMENTS ARE PLACES OF "PUBLIC ACCOMMODATION" UNDER TITLE III OF THE AMERICANS WITH DISABILITIES ACT .......... 16 II. THE PGA TOUR VIOLATED TITLE III’S REASONABLE MODIFICATION PROVISION BY REFUSING TO PERMIT CASEY MARTIN TO RIDE A CART IN ITS TOURNAMENTS .................... 25 CONCLUSION ......................... 37 CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CASES: Anderson v. Little League Baseball, Inc., 794 F. Supp. 342 (D. Ariz. 1992) ........ 21, 27, 28 Arnold v. United Parcel Serv., Inc., 136 F.3d 854 (1st Cir. 1998) .................... 19 Bowers v. National Collegiate Athletic Ass’n, No. 97-2600, 1998 WL 300552 (D.N.J. June 8, 1998) .......... 21 Brown v. Loudoun Golf & Country Club, Inc., 573 F. Supp. 399 (E.D. Va. 1983) .................... 22 Castellano v. City of New York, 142 F.3d 58 (2d Cir. 1998), petition for cert. filed, 66 U.S.L.W. 3790 (U.S. -

Ghosts in the Photographs Oxford’S Post-Rock Sound Explorers Talk Terrifying Auditions, Music from Outer Space and Playing in the Dark

[email protected] @NightshiftMag NightshiftMag nightshiftmag.co.uk Free every month NIGHTSHIFT Issue 277 August Oxford’s Music Magazine 2018 photo: Helen Messenger “The great thing about not having a vocalist is the listener has to think for themselves: they take away whatever the music has made them feel, not what someone has told them to feel.” Ghosts in the Photographs Oxford’s post-rock sound explorers talk terrifying auditions, music from outer space and playing in the dark. Also in this issue: THE CELLAR under threat again. ALPHABET BACKWARDS return. Introducing THE DOLLYMOPS CORNBURY reviewed. plus All your Oxford music news, reviews and gigs for August NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshiftmag.co.uk old self. “This past week Joe has been under general anaesthetic twice: first for neurosurgery and second THE CELLAR faces another fight for its survival following a severe for his leg. The neurosurgery reduction of its capacity last month. consisted of reshaping part of his 15,000 signed a petition to save the venue from closure last year when skull that had collapsed and been the building’s owners, the St Michael’s and All Saints charities put in an compressed into the brain by the application to change the use of the building to retail storage. The plans, weight of the truck’s trailer. The which would have ended live music at The Cellar after 40 years, were operation was successful, but the thrown out by Oxford City Council planning officers. -

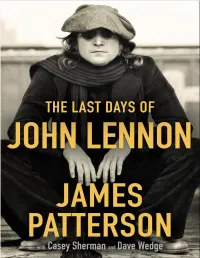

The Last Days of John Lennon

Copyright © 2020 by James Patterson Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce creative works that enrich our culture. The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights. Little, Brown and Company Hachette Book Group 1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104 littlebrown.com twitter.com/littlebrown facebook.com/littlebrownandcompany First ebook edition: December 2020 Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher. The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591. ISBN 978-0-316-42907-8 Library of Congress Control Number: 2020945289 E3-111020-DA-ORI Table of Contents Cover Title Page Copyright Dedication Prologue Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 — Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 Chapter 17 Chapter 18 — Chapter 19 Chapter 20 Chapter 21 Chapter 22 Chapter 23 Chapter 24 -

Cash Box NY Telex: 666123 Tists (Page 7)

UA-LA958-I Featuring ^ “Days Gone Down On United Artists Records in .C 1979 LIBERTY UNITED RECORDS. INC . LOS ANGELES CALIFORNIA 90028 UNITED ARTISTS RECORDS IS A TRADING NAM.F VOLUME XLI — NUMBER 3 — JUNE 2, 1979 FHE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC RECORD WEEKLY C4SH GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher ? 5 MEL ALBERT “An Apple A Day Vice President and General Manager EDITORML CHUCK MEYER value. billboard. Director of Marketing Records are your best entertainment DAVE FULTON With near unanimous agreement that the Considering that consumers are looking for the In Chief Editor aforementioned maxim is true, it is time to let others most for their money, the time is right to let them J.B. CARMICLE realize this secret. know the investment value of music. With minimal General Manager. East Coast And the great hook to this is that it can be done care, a consumer can spend $4-6and haveawork of JIM SHARP Director, Nashville without a costly advertising campaign which also re- art for a lifetime. East Coast Editorial quires executives from various labels to agree to a This simple program needs to be coordinated KEN TERRY East Coast Editor CHARLES PAIKERT budget and a creative approach. Quite simply, a through the RIAA or another industry organization LEO SACKS AARON FUCHS series of phone calls and verbal agreements are all that will take the initiative to promote the concept to West Coast Editorial that is needed. the manufacturers. In a matter of days, the plan ALAN SUTTON. West Coast Editor JOEY BERLIN — RAY TERRACE Whenever a manufacturer advertises his albums, could be instituted. -

When Ziggy Played Guitar: David Bowie, the Man Who Changed the World Pdf

FREE WHEN ZIGGY PLAYED GUITAR: DAVID BOWIE, THE MAN WHO CHANGED THE WORLD PDF Dylan Jones | 224 pages | 01 Apr 2016 | Cornerstone | 9781848093850 | English | London, United Kingdom The Story of David Bowie's Ziggy Stardust David Bowie always had a keen ear for a great guitarist. As we look back at the long career of Bowie, who died January 10, we celebrate both his music and the guitarists who created it with him. Here are nine of the greatest, along with signature tracks that exemplify their contributions. His stinging signature tone, achieved with a Les Paul Custom, became a hallmark of the glam era and inspired guitarists like Randy Rhoads in terms of technique and image. In the video for it, shown below, he mimes using his Kent-branded three-pickup Hagstrom. Belew recalled on his Facebook page how he met Bowie in Berlin during one of the shows. Shall we talk about it over dinner? So the three of us sat down with Frank and the band. Bowie wanted the guitarist to join his group for the subsequent support tour, but Vaughan was reluctant to leave Double Trouble, who had just finished recording their debut, Texas Flood. Gabrels met Bowie in and subsequently joined forces with him in Tin Machine from to The album is full of his beautifully noisy guitar squawks and squeals, which at times recall the digital chatter of a 56k modem. The sound was perfect for When Ziggy Played Guitar: David Bowie album awash in technological isolation, despair and paranoia. GP logo Created with Sketch. -

NY Unofficial Archive V5.2 22062018 TW.Pdf

........................................................................................................................................................................................... THE UNOFFICIAL ARCHIVE: NEIL YOUNG’S “UNRELEASED” SONGS ©Robert Broadfoot 2018 • [email protected] Version 5.2 -YT: 22 June 2018 Page 1 of 98 CONTENTS CONTENTS ............................................................................................................................. 2 FOREWORD .......................................................................................................................... 3 A NOTE ON SOURCES ......................................................................................................... 5 KEY .......................................................................................................................................... 6 I. NEIL YOUNG SONGS NOT RELEASED ON OFFICIAL MEDIA PART ONE THE CANADIAN YEARS .............................................................................. 7 PART TWO THE AMERICAN YEARS ........................................................................... 16 PART THREE EARLY COVERS AND INFLUENCES ........................................................ 51 II. NEIL YOUNG PERFORMING ON THE RELEASED MEDIA AND AT CONCERT APPEARANCES, OF OTHER ARTISTS ..................................................... 63 III. UNRELEASED NEIL YOUNG ALBUM PROJECTS PART ONE DOCUMENTED ALBUM PROJECTS ....................................................... 83 PART TWO SPECULATION -

If There's Any Way We Can Show That Golf Courses

ALWAYS DRIVEN MORE COMFORT. MORE POWER. MORE VERSATILITY. MORE CONTROL. Simply Superior. THE ALL-NEW WORKMAN® GTX SERIES. COMING SPRING 2016. ©2016 The Toro Company. All rights reserved. In conjunction with LET’S DO SOMETHING inspirational You're invited! Association members, golf course operators, industry leaders, friends and supporters will gather for a special evening of networking, recognition and camaraderie. During the event the NGCOA will honor association award winners, including the prestigious Award of Merit recipient, Darius Rucker. Join us on Wednesday, February 10 for the Celebration Darius Rucker Dinner & Awards at the Omni Hotel San Diego. NATIONAL GOLF COURSE OWNERS ASSOCIATION GOLF BUSINESS CONFERENCE San Diego, CA Feb. 8-11 www.golfbusinessconference.com 4 january 2016 different point of view Unlike many management firms, Affinity Management fo- cuses solely on private club operations. Their clients range in size and scope, yet managing partner Damon DeVito says the company’s philosophy is surprisingly simple: listening to members and figuring out how to make their lives better at the club. It isn’t a novel concept, yet in the current era, it’s one that’s all too easily overlooked. a brave new vital world signs The center of any facility is the Few will argue that the golf shop, but golf retail remains game and business are an animal that confounds many struggling, but opinions course owners and operators. vary greatly as to just how To thrive in the modern age sick golf truly is. As the indus- requires imagination and in- try prepares for a new season, novation to stimulate sales and experts measure and debate 40 engage customers. -

ITALIAN BOWIE Tutto Di David Bowie in Italia E Visto Dall'italia INTRODUZIONE

Davide Riccio ITALIAN BOWIE Tutto di David Bowie in Italia e visto dall'Italia INTRODUZIONE Bowie ascoltava la musica italiana? Ogni nazione avrebbe voluto avere i propri Elvis, i propri Beatles, i propri Rolling Stones, il proprio Bob Dylan o il proprio "dio del rock" David Bowie, giusto per fare qualche nome: fare cioè propri i più grandi tra i grandi della storia del rock. O incoronarne in patria un degno corrispettivo. I paesi che non siano britannici o statunitensi perciò di loro lingua franca mondiale sono tuttavia fuori dal gioco: il rock è innanzi tutto un fatto di lingua inglese. Non basta evidentemente cantare in inglese senza essere inglesi, irlandesi o statunitensi et similia per uguagliare in popolarità internazionale gli originari o gli oriundi ed entrare di diritto nella storia internazionale del rock. A volte poi, pur appartenendo alla stessa lingua inglese, il cercarne o crearne un corrispettivo è operazione comunque inutile ai fini del fare o non fare la storia del rock, oltre che un fatto assai discutibile, così come avvenne a esempio negli States in piena Beatlemania con i Monkees, giusto per citare un gruppo nel quale cantava un certo David o Davy Jones, lo stesso che - per evitare omonimia e confusione - portò David Robert Jones, ispirandosi al soldato Jim Bowie e al suo particolare coltello, il cosiddetto Bowie knife, ad attribuirsi un nome d'arte: David Bowie. I Monkees nacquero nel 1965 su idea del produttore discografico Don Kirshner per essere la risposta rivale (anzitutto commerciale) americana ai Beatles, quindi i Beatles americani o gli anti-Beatles. -

Magazin 06-2003

2 Oldie Markt 06/03 Plattenbörsen Oldie Markt 06/03 3 Plattenbörsen 2003 Schallplattenbörsen sind seit einigen Jahren fester Bestandteil der europäischen Musikszene. Steigende Besucherzahlen zeigen, daß sie längst nicht mehr nur Tummelplatz für Insider sind. Neben teu- ren Raritäten bieten die Händler günstige Second-Hand-Platten, Fachzeitschriften, Bücher, Lexika, Poster und Zubehör an. Rund 250 Börsen finden pro Jahr allein in der Bundesrepublik statt. Oldie-Markt veröffentlicht als einzige deutsche Zeit- schrift monatlich den aktuellen Börsen- kalender. Folgende Termine wurden von den Veranstaltern bekanntgegeben: Datum Stadt/Land Veranstaltungs-Ort Veranstalter / Telefon 1. Juni Hildesheim Uni Mensa WIR (051 75) 93 23 59 1. Juni Düsseldorf WBZ am Hauptbahnhof ReRo (02 34) 30 15 60 1. Juni Passau Nibelungenhalle Marylyn Stoschek (085 09) 26 09 1. Juni Graz/Österreich Kolpinghaus Discpoint (00 43) 19 67 75 50 14. Juni Karlsruhe Badnerlandhalle Neureut Ludwig Reichmann (01 79) 697 43 12 15. Juni Braunschweig Stadthalle Maxx pro (053 37) 94 85 31 15. Juni Augsburg FC-Sportheim Haunstetten Peter Pulz (082 31) 41 42 25. Juni Rotterdam/Holland Ahoy ARC (00 31) 229 21 38 91 26. Juni Berlin Statthaus Böcklerpark Kurt Wehrs (030) 425 03 00 29. Juni Dortmund Westfalenhalle Goldsaal Manfred Peters (02 31) 48 19 39 29. Juni Linz/Österreich Volkshaus Bindermichl Marylyn Stoschek (085 09) 26 09 Die Veröffentlichung von Veranstaltungshinweisen auf Schallplattenbörsen ist eine kostenlose Service-Leistung von Oldie-Markt. Ein Anspruch auf Veröffentlichung in obenstehendem Kalender besteht nicht. 2 Oldie Markt 06/03 News Oldie Markt 06/03 3 News • News • News • News • News • News • News * Radiohead kehren auf dem am 10.