Acc Nov2018.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C Powerclmlluling

C PowerClmlluling Everything you need to know about setting up and operating your PowerTower Pro™ system Ma(OS Mac and the Mac OS logo are trademal1<s of Apple Computer, Inc., used under license. Part number 72810 Rev. number 960823 erPro User' ide Part number 72810 Rev. number 960823 Power Computing Corporation © 1996 Power Computing Corporation. All rights reserved. Under copyright laws, this manual may not be copied, in whole or in part, without the written consent of Power Computing. Your rights to the software are governed by the accompanying software license agreement. Power Computing Corporation 2555 North Interstate 35 Round Rock, Texas 78664-2015 (512) 388-6868 Power Computing, the Power Computing logo, PowerTower, and PowerTower Pro are trademarks of Power Computing Corporation. Mac and the Mac as logo are trademarks of Apple Computer, Inc. All other trademarks mentioned are the property of their respective holders. Every effort has been made in this book to distinguish proprietary trademarks from descriptive terms by following the capitalization style used by the manufacturer. Every effort has been made to ensure that the information in this manual is accurate. Power Computing is not responsible for printing or clerical errors. Warranty information about your system may be found beginning on page xv. Other legal notices are found in "Regulatory Information" on page 151. PowerTower Pro User's Guide For Technical Support, Call 1-800-708-6227 Support Information For basic customer and technical support information, as well as product information and other news, visit our Web Site at: http://www.powercc.com Direct or Dealer Support? Customers who purchased systems directly from Power Computing should contact Power Computing for assistance. -

Die Meilensteine Der Computer-, Elek

Das Poster der digitalen Evolution – Die Meilensteine der Computer-, Elektronik- und Telekommunikations-Geschichte bis 1977 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 und ... Von den Anfängen bis zu den Geburtswehen des PCs PC-Geburt Evolution einer neuen Industrie Business-Start PC-Etablierungsphase Benutzerfreundlichkeit wird gross geschrieben Durchbruch in der Geschäftswelt Das Zeitalter der Fensterdarstellung Online-Zeitalter Internet-Hype Wireless-Zeitalter Web 2.0/Start Cloud Computing Start des Tablet-Zeitalters AI (CC, Deep- und Machine-Learning), Internet der Dinge (IoT) und Augmented Reality (AR) Zukunftsvisionen Phasen aber A. Bowyer Cloud Wichtig Zählhilfsmittel der Frühzeit Logarithmische Rechenhilfsmittel Einzelanfertigungen von Rechenmaschinen Start der EDV Die 2. Computergeneration setzte ab 1955 auf die revolutionäre Transistor-Technik Der PC kommt Jobs mel- All-in-One- NAS-Konzept OLPC-Projekt: Dass Computer und Bausteine immer kleiner, det sich Konzepte Start der entwickelt Computing für die AI- schneller, billiger und energieoptimierter werden, Hardware Hände und Finger sind die ersten Wichtige "PC-Vorläufer" finden wir mit dem werden Massenpro- den ersten Akzeptanz: ist bekannt. Bei diesen Visionen geht es um die Symbole für die Mengendarstel- schon sehr früh bei Lernsystemen. iMac und inter- duktion des Open Source Unterstüt- möglichen zukünftigen Anwendungen, die mit 3D-Drucker zung und lung. Ägyptische Illustration des Beispiele sind: Berkley Enterprice mit neuem essant: XO-1-Laptops: neuen Technologien und Konzepte ermöglicht Veriton RepRap nicht Ersatz werden. -

Lnternetting -P

April 1994 $2.95 The Journal of Washington Apple Pi, Ltd. Volume 16, Number 4 lnternetting -p. 9 WordPerfect 3.0-p. 14 ~ Laser Printers -p. 18 Washington Apple Pi General Meeting 4th Saturday • 9:00 a.m. • Burning Tree Elementary School • 7900 Beech Tree Rd. Bethesda, Maryland April 23, 1994 Microsoft: FoxPro May21, 1994 Ares Software Burning• Tree E.S. DATES CHANGE! Bethesda, MD ~@W~ ~om the Beltway (I-495f take Exit 39 onto River lRoad (MD 190) inward toward DC and Bethesda approx. 1 mile. Tum left onto Beech Tree Road. ...A... Burning Tree Elementary 11111 School will be approx. 1/ 4 mile on the left . Northern Virginia ommunity College (NOVA) Table of Contents From the President Volume 16 April 1994 Number 4 TheTCS As It Evolves Club News Artist on Exhibit ........................ 26 by Lorin Evans by Blake Lange WAPHotline ........................ 39, 42 Macintosh Tutorials ................... 28 he operation of an electronic WAP Calendar ..................... 40, 41 Tutorial Registration Form ........ 29 bulletin board such as ours is a ln:dex to Advertisers .................... 2 Special Computer Offer ............. 30 T Classified Advertisements ......... 79 never-ending cycle of moderniza WAP Membership Form ............ 80 tion, expansion, and upgrade. The current TCS is a full replacement Apple II Articles for the Corvus network that was SIGs and Slices Teach a New Trick to a Venerable cajoled and coerced into the 20th Computer century. This first year of opera Stock SIG ..................................... 7 Dave & Joan Jernigan ........... 35 tion has given us a good idea as to by Morris Pelham Notes from the Apple II Vice what our members would like to see Mac Programmers' SIG .............. -

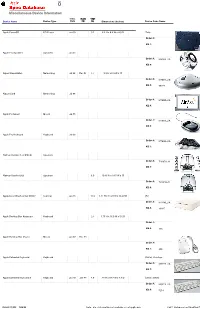

Miscellaneous Device Information

Miscellaneous Device Information Intro. Discont’d Weight Device Name Device Type Date Date (lbs.) Dimensions (inches) Device Code Name Apple PowerCD CD Player Jan 93 3.1 6.5 H x 8.6 W x 4.9 D Tulip Order #: KB #: Apple Pro Speakers Speakers Jan 01 Order #: M8282LL/A KB #: Airport BaseStation Networking Jul 99 Dec 01 1.7 3.2 H x 6.9 W x D Order #: M7601LL/B KB #: 58727 Airport Card Networking Jul 99 Order #: M7600LL/A KB #: Apple Pro Mouse Mouse Jul 00 Order #: M7697LL/A KB #: Apple Pro Keyboard Keyboard Jul 00 Order #: M7696LL/A KB #: Harman Kardon SoundSticks Speakers Order #: T2587LL/A KB #: Harman Kardon iSub Speakers 6.0 10.16 H x 9.15 W x D Order #: T2321LL/A KB #: Apple Color OneScanner 600/27 Scanner Jan 95 13.2 3.11 H x 11.29 W x 16.29 D Rio Order #: M4496LL/A KB #: 19327 Apple Desktop Bus Keyboard Keyboard 2.3 1.75 H x 16.5 W x 5.6 D Order #: KB #: 115 Apple Desktop Bus Mouse Mouse Jan 87 Dec 93 Order #: KB #: 902 Apple Extended Keyboard Keyboard Dörfer, Saratoga Order #: M0115LL/A KB #: Apple Extended Keyboard II Keyboard Jan 93 Jan 99 4.8 .75 H x 18.7 W x 7.7 D Elmer, Nimitz Order #: M0312LL/A KB #: 5214 OCTOBER 15, 2016 12:58 AM Note: n/a = information not available or not applicablePAGE 1 Database Last Modified On Miscellaneous Device Information Intro. Discont’d Weight Device Name Device Type Date Date (lbs.) Dimensions (inches) Device Code Name Apple QuickTake 100 Camera Jan 94 1.1 2.16 H x 5.31 W x 6.1 D Venus Order #: M2613LL/A KB #: 14659 Apple QuickTake 150 Camera 1.1 2.16 H x 5.31 W x 6.1 D Mars Order #: M3791LL/A -

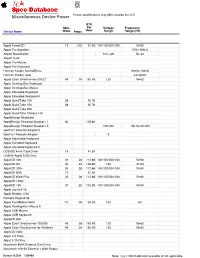

Miscellaneous Device Power Power Specifications May Differ Outside the U.S

Miscellaneous Device Power Power specifications may differ outside the U.S. BTU Max. Per Voltage Frequency Device Name Watts Amps Hour Range Range (Hz) Apple PowerCD 15 .125 51.30 100-125/200-240 50-60 Apple Pro Speakers 70Hz-20kHz Airport BaseStation 100–120 50–60 Airport Card Apple Pro Mouse Apple Pro Keyboard Harman Kardon SoundSticks 200Hz-15kHz Harman Kardon iSub 44-180Hz Apple Color OneScanner 600/27 45 .38 153.90 120 58-62 Apple Desktop Bus Keyboard Apple Desktop Bus Mouse Apple Extended Keyboard Apple Extended Keyboard II Apple QuickTake 100 28 95.76 Apple QuickTake 150 28 95.76 Apple QuickTake 200 Apple QuickTime Camera 100 AppleDesign Keyboard AppleDesign Powered Speakers I 40 136.80 AppleDesign Powered Speakers II 100-240 150 Hz-20 kHz GeoPort Telecom Adapter II GeoPort Telecom Adapter 5 Apple Adjustable Keyboard Apple Standard Keyboard Apple Standard Keyboard II DDS-DC 4mm Tape Drive 15 51.30 UniDisk-Apple 5.25 Drive AppleCD 300 33 .28 112.86 100-125/200-240 50-60 AppleCD SC 40 .33 136.80 120 47-64 AppleCD 300+ 33 .28 112.86 100-125/200-240 50-60 AppleCD 600i 15 51.30 AppleCD 600e Plus 33 .28 112.86 100-125/200-240 50-60 AppleCD 1200i AppleCD 150 30 .25 102.60 100-125/200-240 50-60 Apple Joystick //e Apple Modem 1200 Numeric Keypad IIe Apple Fax Modem 9600 10 .08 34.20 120 60 Apple Desktop Bus Mouse II Apple USB Mouse Apple USB Keyboard AppleCD 800 Apple Color OneScanner 1200/30 45 .38 153.90 120 58-62 Apple Color OneScanner for Windows 45 .38 153.90 120 58-62 AppleCD 300e Apple 3.5 Drive Apple 5.25 Drive Macintosh 800K External Disk Drive Macintosh HDI-20 External 1.4MB Floppy OCTOBER 15, 2016 12:58 AM Note: n/a = information not available or not applicable Miscellaneous Device Power Power specifications may differ outside the U.S. -

Apple Module Identification )

) Apple Module Identification ) PN: 072-8124 ) Copyright 1985-1994 by Apple Computer, Inc. June 1994 ( ( ( Module Identification Table of Contents ) Module Index by Page Number ii Cross Reference by Part Number xv CPU PCBs 1 .1 .1 Keyboards 2.1.1 Power Supplies 3.1.1 Interface Cards 4.1.1 Monitors 5.1.1 Drives 6.1.1 Data Communication 7.1.1 ) Printers 8.1.1 Input Devices 9.1.1 Miscellaneous 10.1.1 ) Module Identification Jun 94 Page i Module Index by Page Number Description Page No. CPU PCBs Macintosh Plus Logic Board 1 .1 .1 Macintosh Plus Logic Board 1.1.2 Macintosh II Logic Board 1.2.1 Macintosh II Logic Board 1.2.2 Macintosh IIx Logic Board 1.2.3 Macintosh Ilx Logic Board 1.2.4 Macintosh Ilcx Logic Board 1.2.5 Macintosh Ilcx Logic Board 1.2.6 Apple 256K SIMM, 120 ns 1.3.1 Apple 256K SIMM, DIP, 120 ns 1.3.2 Apple 256K SIMM, SOJ, SO ns 1.3.3 Apple 1 MB SIMM, 120 ns 1.3.4 Apple 1 MB SIMM, DIP, 120 ns 1.3.5 Apple 1 MB SIMM, SOJ, SO ns 1.3.6 Apple 1 MB SIMM, SOJ, SO ns 1.3.7 Apple 1 MB SIMM, SOJ, SO ns, Parity 1.3.S Apple 2 MB SIMM, SOJ, SO ns 1.3.9 Apple 512K SIMM, SOJ, SO ns 1.3.10 Apple 256K SIMM, VRAM, 100 ns 1.3.11 Apple 256K SIMM, VRAM, SO ns 1.3.12 ( Apple 512K SIMM, VRAM 1.3.13 Macintosh/Macintosh Plus ROMs 1.3.14 Macintosh SE and SE/30 ROMs 1.3.15 Macintosh II ROMs 1.3.16 Apple 4 MB SIMM, 60 ns, 72-Pin 1.3.17 Apple S MB SIMM, 60 ns, 72-Pin 1.3.1S Apple 4 MB x 9 SIMM, SO ns, Parity 1.3.19 Apple 12SK SRAM SIMM, 17 ns 1.3.20 Apple 256K SRAM SIMM, 17 ns 1.3.21 Apple 4SK Tag SRAM SIMM, 14 ns 1.3.22 Macintosh SE Logic Board 1.4.1 Macintosh SE Revised Logic Board 1.4.2 Macintosh SE SOOK Logic Board 1.4.3 Macintosh SE Apple SuperDrive Logic Board 1.4.4 Macintosh SE/30 Logic Board 1.4.5 Macintosh SE/30 Logic Board 1.4.6 Macintosh SE Analog Board 1.4.7 Macintosh SE Video Board 1.4.S ( Macintosh Classic Logic Board 1.5.1 Macintosh Classic Power Sweep Board (110 V) Rev. -

Washington Apple Pi Journal, July-August 1994

July I August 1994 $2.95 The Journal of Washington Apple Pi, Ltd. Erasing the miles with e-mail-p. 18 Networking Primer-p. 31 Mac Music with MIDI-p.53 Forget Gas, Food &Lodging On the Information Superhighway this is the only stop you'll need. Don't want to be bypassed on the Information Add a stop at any of our upcoming MAC Superhighway? Then plan a detour to MAC WORLD Expo events to your information WORLD Expo. Here you'll test drive the products roadmap. With shows in San Francisco, Boston and services that enable you to maximize the and Toronto, we're just around the next bend. potential of the Macintosh now and down the road. Please send me more information on MACWORLD Expo. I am interested in: 0 Exhibiting 0 Attending MACWORLD Expo is your chance to see hun 0 San Francisco 0 Boston 0 Toronto dreds of companies presenting the latest in turbo Na me ________________ charged Macintosh technology. Make side by side Title----------------- comparisons of thousands of Macintosh products. Company _______________ Learn from the experts how to fine-tune your sys Address ________________ tem and what products will keep your engine run City/State/Zip___________ ___ ning smooth. Attend a variety of information packed conference programs that provide the skills Phone Fa,,,,___ _____ Mail to: Mitch Hall Associates, 260 Milton St., Dedham, MA 02026 and knowledge to put you in the driver's seat. So Or Fax to: 6 17-361-3389 Phone: 617-361-8000 pull on in and take that new Mac for a spin. -

Apple Confidential 2.0 the Definitive History of the World's Most Colorful

vi Reviewers love Apple Confidential “The Apple story itself is here in all its drama.” New York Times Book Review “An excellent textbook for Apple historians.” San Francisco Chronicle “Written with humor, respect, and care, it absolutely is a must-read for every Apple fan.” InfoWorld “Pretty much irresistible is the only way to describe this quirky, highly detailed and illustrated look at the computer maker’s history.” The Business Reader Review “The book is full of basic facts anyone will appreciate. But it’s also full of interesting extras that Apple fanatics should love.” Arizona Republic “I must warn you. This 268-page book is hard to put down for a MacHead like me, and probably you too.” MacNEWS “You’ll love this book. It’s a wealth of information.” AppleInsider “Rife with gems that will appeal to Apple fanatics and followers of the computer industry.” Amazon.com “Mr. Linzmayer has managed to deliver, within the confines of a single book, just about every juicy little tidbit that was ever leaked from the company.” MacTimes “The most entertaining book about Apple yet to be published.” Booklist i …and readers love it too! “Congratulations! You should be very proud. I picked up Apple Confidential and had a hard time putting it down. Obviously, you invested a ton of time in this. I hope it zooms off the shelves.” David Lubar, Nazareth, PA “I just read Apple Confidentialfrom cover to cover…you have written a great book!” Jason Whong, Rochester, NY “There are few books out there that reveal so much about Apple and in such a fun and entertaining manner. -

FWB CD-ROM Toolkit Prefs, and FWB CDT Remote

® ® ª CD-ROM ToolKit User Guides FWB, Inc. 1555 Adams Drive Menlo Park, CA 94025-1439 ¥ Phone number: 415-325-4392 ¥ Technical Support fax number: 415-833-4662 E-mail addresses ¥ AppleLink: FWB ¥ eWorld: FWB.INC ¥ America Online: FWBINC ¥ CompuServe: 71320,1034 ¥ Internet: [email protected] End-User Software License Agreement DO NOT USE THIS SOFTWARE UNTIL YOU HAVE CAREFULLY READ THIS AGREEMENT AND AGREE TO THE TERMS OF THIS LICENSE. BY USING THE ENCLOSED SOFTWARE, YOU ARE AGREEING TO THE TERMS OF THIS LICENSE. The software license agreement for this program is displayed in this manual so you can read it before installing the program. INSTALLING THE PROGRAM OR USE OF THE MATERIALS ENCLOSED WILL CONSTITUTE YOUR ACCEPTANCE OF THE TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF THIS SOFTWARE LICENSE AGREEMENT. If you do not agree to the terms of this software license agreement, do not install the software and promptly return the package to the place of purchase for a full refund of all money that you paid for the product. In return for purchasing a license to use the computer programs, known as CD-ROM ToolKit (Software) contained in this package, and for purchasing documentation included in this package, you agree to the following terms and conditions: 1. License. The Software enclosed is licensed, not sold, to you by FWB Software, Inc. (FWB) for use under the terms of this soft- ware license. This non-exclusive license allows you to: a. Use the Software only on a SINGLE computer at any one time. You may only use the software on one CPU and only on drives physically connected to that single CPU. -

Apple Storia

Apple Edizione 0.5 21/08/2006 Nota: L'attuale versione del libro è reperibile all'indirizzo: http://it.wikibooks.org/wiki/Apple 1 Indice dei contenuti Apple....................................................................................................................................................1 Introduzione..........................................................................................................................................4 Storia.....................................................................................................................................................5 Le origini..........................................................................................................................................5 I primi anni.......................................................................................................................................5 Il Macintosh.....................................................................................................................................6 Anni recenti......................................................................................................................................7 Fondatori.............................................................................................................................................11 Steve Jobs.......................................................................................................................................11 Steve Wozniak...............................................................................................................................13 -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27

Case 5:10-cv-03216-JF Document 85 Filed 11/22/11 Page 1 of 22 1 KILPATRICK TOWNSEND & STOCKTON LLP THEODORE T. HERHOLD (State Bar No. 122895) **E-Filed 11/22/2011** 2 ANDREW T. OLIVER (State Bar No. 226098) ROBERT D. TADLOCK (State Bar No. 238479) 3 379 Lytton Avenue Palo Alto, CA 94301 4 Telephone: (650) 326-2400 Facsimile: (650) 326-2422 5 Email: [email protected] [email protected] 6 [email protected] 7 Attorneys for Plaintiff APPLE INC. 8 LEWIS BRISBOIS BISGAARD & SMITH LLP 9 JON E. HOKANSON (State Bar No. 118829) 221 N. Figueroa St., Suite 1200 10 Los Angeles, CA 90012 Telephone: (213) 250-1800 11 Facsimile: (213) 250-7900 Email: [email protected] 12 LEWIS BRISBOIS BISGAARD & SMITH LLP 13 ALAN J. HAUS, SB# 111566 E-Mail: [email protected] 14 One Sansome Street, Suite 1400 San Francisco, CA 94104 15 Telephone:415.362.2580 Facsimile: 415.434.0882 16 Attorneys for Defendants, 17 EFORCITY CORPORATION, ACCSTATION INC., ITRIMMING INC. 18 and EVERYDAYSOURCE INC. 19 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 20 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 21 APPLE INC., a California corporation, Civil Action No. CV10-03216 JF (HRL) 22 Plaintiff, 23 v. FINAL JUDGMENT AND PERMANENT 24 INJUNCTION ON CONSENT EFORCITY CORPORATION, a California 25 corporation; ACCSTATION INC., a California corporation; ITRIMMING INC., a 26 California corporation; EVERYDAYSOURCE INC., a California 27 corporation; UNITED INTEGRAL INC., a California corporation; CRAZYONDIGITAL, 28 INC., a California corporation; and FINAL JUDGMENT AND INJUNCTION UPON CONSENT CASE NO. 10-CV-03216 JF (HRL) Case 5:10-cv-03216-JF Document 85 Filed 11/22/11 Page 2 of 22 1 BOXWAVE CORPORATION, a Nevada corporation; and DOES 1 through 20, 2 inclusive, Defendants. -

Miscellaneous Device Memory No

Miscellaneous Device Memory No. of ROM Min. Max. Memory RAM RAM RAM Device Name Size RAM RAM Slots Type Speed Sizes Apple PowerCD Apple Pro Speakers Airport BaseStation Airport Card Apple Pro Mouse Apple Pro Keyboard Harman Kardon SoundSticks Harman Kardon iSub Apple Color OneScanner Apple Desktop Bus Apple Desktop Bus Mouse Apple Extended Keyboard Apple Extended Keyboard II Apple QuickTake 100 1MB 1 Flash Apple QuickTake 150 1MB 1 Flash Apple QuickTake 200 2MB 1 SmartM Apple QuickTime Camera AppleDesign Keyboard AppleDesign Powered AppleDesign Powered GeoPort Telecom Adapter II GeoPort Telecom Adapter Apple Adjustable Keyboard Apple Standard Keyboard Apple Standard Keyboard II DDS-DC 4mm Tape Drive UniDisk-Apple 5.25 Drive AppleCD 300 AppleCD SC AppleCD 300+ AppleCD 600i AppleCD 600e Plus AppleCD 1200i AppleCD 150 Apple Joystick //e Apple Modem 1200 Numeric Keypad IIe Apple Fax Modem 9600 Apple Desktop Bus Mouse II Apple USB Mouse Apple USB Keyboard AppleCD 800 Apple Color OneScanner Apple Color OneScanner for AppleCD 300e Apple 3.5 Drive Apple 5.25 Drive Macintosh 800K External Macintosh HDI-20 External Apple HD 20 OCTOBER 15, 2016 12:59 AM Note: n/a = information not available or not applicable Miscellaneous Device Memory No. of ROM Min. Max. Memory RAM RAM RAM Device Name Size RAM RAM Slots Type Speed Sizes Apple Tape Backup 40SC Apple Tape Backup 80SC Apple External Hard Drive Macintosh LC Microphone Apple Headphones Apple Presentation System Macintosh Keyboard Macintosh 512K Keyboard Macintosh 512K Mouse Macintosh 400K Disk Drive