Reforming the Chinese Sports System: a Case Study of the Hebei

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Master's Degree Programme

Master’s Degree programme in Lingue, economie e istituzioni dell’Asia e dell’Africa mediterranea “Second Cycle (D.M. 270/2004)” Final Thesis The Evolving Framework of Chinese Outbound M&A The case of Inter Supervisor Ch. Prof. Renzo Riccardo Cavalieri Assistant supervisor Ch. Prof. Franco Gatti Graduand Valentina Coccato 841509 Academic Year 2016/2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS 前言 ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Chapter One: China’s Outbound M&A ............................................................................... 10 1.1 Chinese Outward Foreign Direct Investment ............................................................ 10 1.2 Government role and regulations .............................................................................. 14 1.3 Policymaking actors .................................................................................................. 16 1.3.1 Top Level ............................................................................................................ 16 1.3.2 Second level ........................................................................................................ 17 1.3.3 Third level ........................................................................................................... 18 1.3.4 Fourth level ......................................................................................................... 20 1.4 OFDI Approval Procedure: A Changing Framework ............................................... -

EDUCATION in CHINA a Snapshot This Work Is Published Under the Responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD

EDUCATION IN CHINA A Snapshot This work is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. Photo credits: Cover: © EQRoy / Shutterstock.com; © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © astudio / Shutterstock.com Inside: © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © li jianbing / Shutterstock.com; © tangxn / Shutterstock.com; © chuyuss / Shutterstock.com; © astudio / Shutterstock.com; © Frame China / Shutterstock.com © OECD 2016 You can copy, download or print OECD content for your own use, and you can include excerpts from OECD publications, databases and multimedia products in your own documents, presentations, blogs, websites and teaching materials, provided that suitable acknowledgement of OECD as source and copyright owner is given. All requests for public or commercial use and translation rights should be submitted to [email protected]. Requests for permission to photocopy portions of this material for public or commercial use shall be addressed directly to the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) at [email protected] or the Centre français d’exploitation du droit de copie (CFC) at [email protected]. Education in China A SNAPSHOT Foreword In 2015, three economies in China participated in the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment, or PISA, for the first time: Beijing, a municipality, Jiangsu, a province on the eastern coast of the country, and Guangdong, a southern coastal province. -

Sports and Physical Education in China

Sport and Physical Education in China Sport and Physical Education in China contains a unique mix of material written by both native Chinese and Western scholars. Contributors have been carefully selected for their knowledge and worldwide reputation within the field, to provide the reader with a clear and broad understanding of sport and PE from the historical and contemporary perspectives which are specific to China. Topics covered include: ancient and modern history; structure, administration and finance; physical education in schools and colleges; sport for all; elite sport; sports science & medicine; and gender issues. Each chapter has a summary and a set of inspiring discussion topics. Students taking comparative sport and PE, history of sport and PE, and politics of sport courses will find this book an essential addition to their library. James Riordan is Professor and Head of the Department of Linguistic and International Studies at the University of Surrey. Robin Jones is a Lecturer in the Department of PE, Sports Science and Recreation Management, Loughborough University. Other titles available from E & FN Spon include: Sport and Physical Education in Germany ISCPES Book Series Edited by Ken Hardman and Roland Naul Ethics and Sport Mike McNamee and Jim Parry Politics, Policy and Practice in Physical Education Dawn Penney and John Evans Sociology of Leisure A reader Chas Critcher, Peter Bramham and Alan Tomlinson Sport and International Politics Edited by Pierre Arnaud and James Riordan The International Politics of Sport in the 20th Century Edited by James Riordan and Robin Jones Understanding Sport An introduction to the sociological and cultural analysis of sport John Home, Gary Whannel and Alan Tomlinson Journals: Journal of Sports Sciences Edited by Professor Roger Bartlett Leisure Studies The Journal of the Leisure Studies Association Edited by Dr Mike Stabler For more information about these and other titles published by E& FN Spon, please contact: The Marketing Department, E & FN Spon, 11 New Fetter Lane, London, EC4P 4EE. -

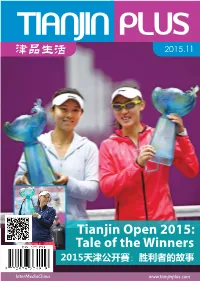

Tianjin Open 2015: Tale of the Winners 2015天津公开赛:胜利者的故事

2015.082015.082015.08 Tianjin Open 2015: Tale of the Winners 2015天津公开赛:胜利者的故事 InterMediaChina www.tianjinplus.com IST offers your children a welcoming, inclusive international school experience, where skilled and committed teachers deliver an outstanding IB education in an environment of quality learning resources and world-class facilities. IST is... fully accredited by the Council of International Schools (CIS) IST is... fully authorized as an International Baccalaureate World School (IB) IST is... fully accredited by the Western Association of Schools and Colleges (WASC) IST is... a full member of the following China and Asia wide international school associations: ACAMIS, ISAC, ISCOT, EARCOS and ACMIBS 汪正影像艺术 VISUAL ARTS Wang Zheng International Children Photography Agency 汪 正·天 津 旗下天津品牌店 ■婴有爱婴幼儿童摄影 ■韩童街拍工作室 ■顽童儿童摄影会馆 ■汪叔叔专业儿童摄影 ■素摄儿童摄影会馆 转 Website: www.istianjin.org Email: [email protected] Tel: 86 22 2859 2003/5/6 ■ Prince&Princess 摄影会馆 ■韩爱儿童摄影会馆 ■本真儿童摄影会馆 4006-024-521 5 NO.22 Weishan South Road, Shuanggang, Jinnan District, Tianjin 300350, P.R.China 14 2015 2015 CONTENTS 11 CONTENTS 11 Calendar 06 Beauty 38 46 Luscious Skin Sport & Fitness 40 Partner Promotions 09 Tianjin Open 2015: A Tale of Upsets, Close Calls and Heroic Performances Art & Culture 14 How to 44 Eat me. Tianjin style. How to Cope with Missing Home Feature Story 16 Beijing Beat 46 16 The Rise of Craft Beer in China Off the Tourist Trail: Perfect Family Days Out Cover Story 20 Special Days 48 Tianjin Open 2015: Tale of the Winners Special Days in November 2015 Restaurant -

The Business of Sport in China

Paper size: 210mm x 270mm LONDON 26 Red Lion Square London WC1R 4HQ United Kingdom Tel: (44.20) 7576 8000 Fax: (44.20) 7576 8500 E-mail: [email protected] NEW YORK 111 West 57th Street New York The big league? NY 10019 United States Tel: (1.212) 554 0600 The business of sport in China Fax: (1.212) 586 1181/2 E-mail: [email protected] A report from the Economist Intelligence Unit HONG KONG 6001, Central Plaza 18 Harbour Road Wanchai Hong Kong Sponsored by Tel: (852) 2585 3888 Fax: (852) 2802 7638 E-mail: [email protected] The big league? The business of sport in China Contents Preface 3 Executive summary 4 A new playing field 7 Basketball 10 Golf 12 Tennis 15 Football 18 Outlook 21 © Economist Intelligence Unit 2009 1 The big league? The business of sport in China © 2009 Economist Intelligence Unit. All rights reserved. All information in this report is verified to the best of the author’s and the publisher’s ability. However, the Economist Intelligence Unit does not accept responsibility for any loss arising from reliance on it. Neither this publication nor any part of it may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Economist Intelligence Unit. 2 © Economist Intelligence Unit 2009 The big league? The business of sport in China Preface The big league? The business of sport in China is an Economist Intelligence Unit briefing paper, sponsored by Mission Hills China. -

China's Sports Heroes: Nationalism, Patriotism, and Gold Medal

The International Journal of the History of Sport ISSN: 0952-3367 (Print) 1743-9035 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fhsp20 China’s Sports Heroes: Nationalism, Patriotism, and Gold Medal Lu Zhouxiang & Fan Hong To cite this article: Lu Zhouxiang & Fan Hong (2019) China’s Sports Heroes: Nationalism, Patriotism, and Gold Medal, The International Journal of the History of Sport, 36:7-8, 748-763, DOI: 10.1080/09523367.2019.1657839 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2019.1657839 Published online: 30 Sep 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 268 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fhsp20 THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF THE HISTORY OF SPORT 2019, VOL. 36, NOS. 7–8, 748–763 https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2019.1657839 China’s Sports Heroes: Nationalism, Patriotism, and Gold Medal Lu Zhouxianga and Fan Hongb aSchool of Modern Languages, Literatures and Cultures, National University of Ireland, Maynooth, Ireland; bThe University of Bangor, Bangor, UK ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Sport has been of great importance to the construction of China; hero; politics; Chinese national consciousness during the past century. This art- nationalism; icle examines how China’s sport celebrities have played their part sports patriotism in nation building and identity construction. It points out that Chinese athletes’ participation in international sporting events in the first half of the twentieth century demonstrated China’s motivation to stay engaged with the world, and therefore led to their being regarded as national heroes. -

Yao Ming, Globalization, and the Cultural Politics of Us-C

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 From "Ping-Pong Diplomacy" to "Hoop Diplomacy": Yao Ming, Globalization, and the Cultural Politics of U.S.-China Relations Pu Haozhou Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF EDUCATION FROM “PING-PONG DIPLOMACY” TO “HOOP DIPLOMACY”: YAO MING, GLOBALIZATION, AND THE CULTURAL POLITICS OF U.S.-CHINA RELATIONS By PU HAOZHOU A Thesis submitted to the Department of Sport Management in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2012 Pu Haozhou defended this thesis on June 19, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Michael Giardina Professor Directing Thesis Joshua Newman Committee Member Jeffrey James Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I’m deeply grateful to Dr. Michael Giardina, my thesis committee chair and advisor, for his advice, encouragement and insights throughout my work on the thesis. I particularly appreciate his endless inspiration on expanding my vision and understanding on the globalization of sports. Dr. Giardina is one of the most knowledgeable individuals I’ve ever seen and a passionate teacher, a prominent scholar and a true mentor. I also would like to thank the other members of my committee, Dr. Joshua Newman, for his incisive feedback and suggestions, and Dr. Jeffrey James, who brought me into our program and set the role model to me as a preeminent scholar. -

Sport in Asia: Globalization, Glocalization, Asianization

7 Sport in Asia: Globalization, Glocalization, Asianization Peter Horton James Cook University, Townsville Australia 1. Introduction Sport is now a truly global cultural institution, one that is no longer the preserve of occidental culture or dominated and organized by Western nations, the growing presence and power of non-occidental culture and individual nations now makes it a truly globalized product and commodity. The insatiable appetite for sport of the enormous Asian markets is redirecting the global flow of sport, with the wider Asia Pacific region now providing massive new audiences for televised sports as the economies of the region continue their growth. This chapter will consider the process of sport’s development in the Asian and the wider Asia Pacific context through the latter phases of the global sportization process (Maguire, 1999). As the locus of the centre of gravity of global geopolitical power is shifting to the Asia Pacific region away from the Euro-Atlantic region the hegemonic sports are now assuming a far more cosmopolitan character and are being reshaped by Asian influences. This has been witnessed in the major football leagues in Europe, particularly the English Premier League and is manifest in the Indian Premier League cricket competition, which has spectacularly changed the face of cricket world-wide through what could be called its ‘Bollywoodization’(Rajadhyaskha, 2003). Perhaps this reflects ‘advanced’ sportization (Maguire, 1999) with the process going beyond the fifth global sportization phase in sport’s second globalization with ‘Asianization’ becoming a major cultural element vying with the previously dominant cultural traditions of Westernization and Americanization? This notion will be discussed in this paper by looking at Asia’s impact on the development of sport, through the three related lenses of: sportization; the global sports formation and, the global media-sport comple. -

Research on the Development of Sports Music from the Perspective of Olympic Theme Song

Journal of Frontiers in Sport Research DOI: 10.23977/jfsr.2021.010107 Clausius Scientific Press, Canada Volume 1, Number 1, 2021 Research on the Development of Sports Music from the Perspective of Olympic Theme Song Na Zhou School of Music, Shanxi University, Taiyuan, 030006, Shanxi, China Keywords: Sports music, Olympic music, Development Abstract: As one of the most important sports music, the theme song of the Olympic Games is of great significance in the development of sports music, this paper analyzes the correlation and relevant situation of the Olympic music, discusses the relationship between sports and music and the Olympic Games and music, and makes a certain summary of the development characteristics of sports music, the implications of post-development are profound. 1. Introduction 1.1 The Development of Sports Songs in China Before the Reform and Opening Up In the middle of the last century, China's sports development is still in its embryonic stage, and the types and quantities of sports songs are very scarce. The theme songs of some sports-related films and TV programs belong to the category of sports music, however, in view of the backward means of communication, the scope of communication is not far-reaching, in the context of that era, China's policy and environmental impact, these songs in the theme more like traditional revolutionary songs. In the next 10 years, due to the development of table tennis in China, the asian-african table tennis invitational tournament came into being. In this competition, a piece of music related to athletes was officially born, this piece of music is also equivalent to the opening piece of China's sports program, in the present many events related to the Games will be heard on the spot, this “athletes March. -

China's Football Dream

China Soccer Observatory China’s Football Dream nottingham.ac.uk/asiaresearch/projects/cso Edited by: Jonathan Sullivan University of Nottingham Asia Research Institute Contents Domestic Policy. 1. The development of football in China under Xi Jinping. Tien-Chin Tan and Alan Bairner. 2. - Defining characteristics, unintended consequences. Jonathan Sullivan. 3. -Turn. Ping Wu. 4. Emerging challenges for Chinese soccer clubs. Anders Kornum Thomassen. 5. Jonathan Sullivan. 6. Can the Foreign Player Restriction and U-23 Rule improve Chinese football? Shuo Yang and Alan Bairner. 7. The national anthem dilemma - Contextualising political dissent of football fans in Hong Kong. Tobais Zuser. 8. A Backpass to Mao? - Regulating (Post-)Post-Socialist Football in China. Joshua I. Newman, Hanhan Xue and Haozhou Pu. 9. Simon Chadwick. 1 Marketing and Commercial Development. 1. Xi Simon Chadwick. 2. Who is the Chinese soccer consumer and why do Chinese watch soccer? Sascha Schmidt. 3. Corporate Social Responsibility and Chinese Professional Football. Eric C. Schwarz and Dongfeng Liu. 4. Chinese Football - An industry built through present futures, clouds, and garlic? David Cockayne. 5. Benchmarking the Chinese Soccer Market: What makes it so special? Dennis-Julian Gottschlich and Sascha Schmidt. 6. European soccer clubs - How to be successful in the Chinese market. Sascha Schmidt. 7. The Sports Industry - the Next Big Thing in China? Dongfeng Liu. 8. Online streaming media- Bo Li and Olan Scott. 9. Sascha Schmidt. 10. E-sports in China - History, Issues and Challenges. Lu Zhouxiang. 11. - Doing Business in Beijing. Simon Chadwick. 12. Mark Skilton. 2 Internationalisation. 1. c of China and FIFA. Layne Vandenberg. -

Tennis Time in Tianjin! Tianjin Open 6-12 October 天津网球公开赛!

2014.10 16 Tennis Time in Tianjin! Tianjin Open 6-12 October 天津网球公开赛! InterMediaChina www.tianjinplus.com Managing Director J. Hernan [email protected] Managing Editor Jeff Williams [email protected] Editors Elvira Cheng, Michelle Piao [email protected] Contributors Cathy Perez, Josh Cooper, Andrea Klopper, Abbie Armstrong Ben Hoskins, Anna L. Plurabelle Silvina Pardo, Aida Yan, Malaka Yattigala Designer Freelance Writers, Editors & Hu Yingzhe Proofreaders Needed at Tianjin’s Premier Lifestyle Magazine! Marketing, Events & Promotions Danni Zhang, Jenny Wang, Carolin Chang We are looking for: [email protected] · Native or high level English speakers who also have excellent writing skills. Photographer · A good communicator who has the ability to work as Wang Yifang part of a diverse and dynamic team. · Basic Chinese language abilities and experience in Distribution journalism and/or editing are preferred but not crucial. Lei Hongzhi If you are interested in contributing to our magazine, distribution@tianjinplus. com please send your CV and a brief covering letter to [email protected] Advertising Agency InterMediaChina advertising@tianjinplus. com Publishing Date October 2014 Tianjin Plus is a Lifestyle Magazine. For Members ONLY www. tianjinplus. com Tel: +86 22 2576 0956 ISSN 2076-3743 2014 2014 CONTENTS 10 CONTENTS 10 October Calendar 08 Education IST 36 16 Wellington 37 Partner Promotions 10 Sports & Fitness 38 Art & Culture 12 Are You Ready to Get Insane? 36 National Day: Celebrating the Birth of a Nation -

History of Baseball Development

University of Alberta MLB: The Next NBA China? The Importance of Isomorphic Process for MLB in China By Ye Liang A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Faculty of Physical Education & Recreation ©Ye Liang Fall 2012 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. ABSTRACT Major League Baseball (MLB) has taken a series of actions over the past five years to penetrate the Chinese market. Watching the success of the National Basketball Association (NBA), MLB can easily identify opportunities in the Chinese market of 1.3 billion people. However, in comparison with an established American market, the Chinese market presents its own challenges and unknown factors, which are challenging the success of MLB’s marketing strategies. With over 20 years’ development in China, the NBA has become a model for the MLB. The focus of this paper is to explore the mimetic and coercive mechanisms of the Isomorphic process being used on the MLB.