China's Sports Heroes: Nationalism, Patriotism, and Gold Medal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Master's Degree Programme

Master’s Degree programme in Lingue, economie e istituzioni dell’Asia e dell’Africa mediterranea “Second Cycle (D.M. 270/2004)” Final Thesis The Evolving Framework of Chinese Outbound M&A The case of Inter Supervisor Ch. Prof. Renzo Riccardo Cavalieri Assistant supervisor Ch. Prof. Franco Gatti Graduand Valentina Coccato 841509 Academic Year 2016/2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS 前言 ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Chapter One: China’s Outbound M&A ............................................................................... 10 1.1 Chinese Outward Foreign Direct Investment ............................................................ 10 1.2 Government role and regulations .............................................................................. 14 1.3 Policymaking actors .................................................................................................. 16 1.3.1 Top Level ............................................................................................................ 16 1.3.2 Second level ........................................................................................................ 17 1.3.3 Third level ........................................................................................................... 18 1.3.4 Fourth level ......................................................................................................... 20 1.4 OFDI Approval Procedure: A Changing Framework ............................................... -

Women's 3000M Steeplechase

Games of the XXXII Olympiad • Biographical Entry List • Women Women’s 3000m Steeplechase Entrants: 47 Event starts: August 1 Age (Days) Born SB PB 1003 GEGA Luiza ALB 32y 266d 1988 9:29.93 9:19.93 -19 NR Holder of all Albanian records from 800m to Marathon, plus the Steeplechase 5000 pb: 15:36.62 -19 (15:54.24 -21). 800 pb: 2:01.31 -14. 1500 pb: 4:02.63 -15. 3000 pb: 8:52.53i -17, 8:53.78 -16. 10,000 pb: 32:16.25 -21. Half Mar pb: 73:11 -17; Marathon pb: 2:35:34 -20 ht EIC 800 2011/2013; 1 Balkan 1500 2011/1500; 1 Balkan indoor 1500 2012/2013/2014/2016 & 3000 2018/2020; ht ECH 800/1500 2012; 2 WSG 1500 2013; sf WCH 1500 2013 (2015-ht); 6 WIC 1500 2014 (2016/2018-ht); 2 ECH 3000SC 2016 (2018-4); ht OLY 3000SC 2016; 5 EIC 1500 2017; 9 WCH 3000SC 2019. Coach-Taulant Stermasi Marathon (1): 1 Skopje 2020 In 2021: 1 Albanian winter 3000; 1 Albanian Cup 3000SC; 1 Albanian 3000/5000; 11 Doha Diamond 3000SC; 6 ECP 10,000; 1 ETCh 3rd League 3000SC; She was the Albanian flagbearer at the opening ceremony in Tokyo (along with weightlifter Briken Calja) 1025 CASETTA Belén ARG 26y 307d 1994 9:45.79 9:25.99 -17 Full name-Belén Adaluz Casetta South American record holder. 2017 World Championship finalist 5000 pb: 16:23.61 -16. 1500 pb: 4:19.21 -17. 10 World Youth 2011; ht WJC 2012; 1 Ibero-American 2016; ht OLY 2016; 1 South American 2017 (2013-6, 2015-3, 2019-2, 2021-3); 2 South American 5000 2017; 11 WCH 2017 (2019-ht); 3 WSG 2019 (2017-6); 3 Pan-Am Games 2019. -

Online Corruption-Reporting, Internet Censorship, and the Limits of Responsive Authoritarianism

Online Corruption-Reporting, Internet Censorship, and the Limits of Responsive Authoritarianism by Jack Hoskins BA, University of Victoria, 2015 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History © Jack Hoskins, 2017 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Online Corruption Reporting, Internet Censorship, and the Limits of Responsive Authoritarianism by Jack Hoskins BA, University of Victoria, 2015 Supervisory Committee Dr. Guoguang Wu (Department of History) Supervisor Dr. Colin Bennett (Department of Political Science) Outside Member iii Abstract This thesis traces the development of the Chinese government’s attempts to solicit corruption reports from citizens via online platforms such as websites and smartphone applications. It argues that this endeavour has proven largely unsuccessful, and what success it has enjoyed is not sustainable. The reason for this failure is that prospective complainants are offered little incentive to report corruption via official channels. Complaints on social media require less effort and are more likely to lead to investigations than complaints delivered straight to the government, though neither channel is particularly effective. The regime’s concern for social stability has led to widespread censorship of corruption discussion on social media, as well as a slew of laws and regulations banning the behaviour. Though it is difficult to predict what the long- term results of these policies will be, it seems likely that the regime’s ability to collect corruption data will remain limited. -

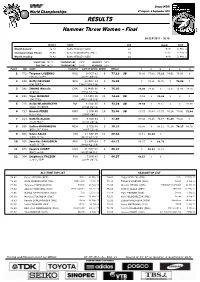

AT-HT-W-F--A--.RS1.Pdf

Daegu (KOR) World Championships 27 August - 4 September 2011 RESULTS Hammer Throw Women - Final 04 SEP 2011 - 18:15 RESULT NAME AGE VENUE DATE World Record 79.42 Betty HEIDLER (GER) 28 Halle 21 May 11 Championships Record 77.96 Anita WLODARCZYK (POL) 24 Berlin 22 Aug 09 World Leading 79.42 Betty HEIDLER (GER) 28 Halle 21 May 11 START TIME 18:10 TEMPERATURE 28°C HUMIDITY 54% END TIME 19:37 TEMPERATURE 27°C HUMIDITY 54% PLACE BIB NAME COUNTRY DATE OF BIRTH ORDER RESULT 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 772 Tatyana LYSENKO RUS 9 OCT 83 6 77.13 SB 76.80 77.09 77.13 74.51 75.05 X 타티아나 리센코 1983년 10월 9일 2 420 Betty HEIDLER GER 14 OCT 83 3 76.06 X 73.96 74.70 X 76.06 X 베티 하이들러 1983년 10월 14일 3 246 ZHANG Wenxiu CHN 22 MAR 86 4 75.03 75.03 74.31 X 73.17 71.86 74.79 장 웬시우 1986년 3월 22일 4 285 Yipsi MORENO CUB 19 NOV 80 12 74.48 SB 73.29 X 74.48 X X X 입시 모레노 1980년 11월 19일 5 715 Anita WLODARCZYK POL 8 AUG 85 8 73.56 SB 73.56 X 72.61 X X 72.65 아니타 볼다르치크 1985년 8월 8일 6 733 Bianca PERIE ROU 1 JUN 90 10 72.04 SB 67.73 70.40 67.75 70.24 70.91 72.04 비앙카 페리 1990년 6월 1일 7 424 Kathrin KLAAS GER 8 FEB 84 1 71.89 67.02 70.18 70.67 71.89 70.44 X 카트린 클라스 1984년 2월 8일 8 650 Zalina MARGHIEVA MDA 5 FEB 88 5 70.27 69.99 X 68.13 70.24 70.27 68.76 잘리나 마르기에바 1988년 2월 5일 9 506 Silvia SALIS ITA 17 SEP 85 11 69.88 68.61 69.88 X 실비아 살리스 1985년 9월 17일 10 105 Jennifer DAHLGREN ARG 21 APR 84 7 69.72 68.27 X 69.72 헤니퍼 달그렌 1984년 4월 21일 11 928 Jessica COSBY USA 31 MAY 82 9 68.91 X 68.91 68.15 제시카 코스비 1982년 5월 31일 12 364 Stéphanie FALZON FRA 7 JAN 83 2 66.57 66.57 X X 스테파니 팔존 1983년 1월 7일 ALL-TIME TOP LIST -

EDUCATION in CHINA a Snapshot This Work Is Published Under the Responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD

EDUCATION IN CHINA A Snapshot This work is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. Photo credits: Cover: © EQRoy / Shutterstock.com; © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © astudio / Shutterstock.com Inside: © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © li jianbing / Shutterstock.com; © tangxn / Shutterstock.com; © chuyuss / Shutterstock.com; © astudio / Shutterstock.com; © Frame China / Shutterstock.com © OECD 2016 You can copy, download or print OECD content for your own use, and you can include excerpts from OECD publications, databases and multimedia products in your own documents, presentations, blogs, websites and teaching materials, provided that suitable acknowledgement of OECD as source and copyright owner is given. All requests for public or commercial use and translation rights should be submitted to [email protected]. Requests for permission to photocopy portions of this material for public or commercial use shall be addressed directly to the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) at [email protected] or the Centre français d’exploitation du droit de copie (CFC) at [email protected]. Education in China A SNAPSHOT Foreword In 2015, three economies in China participated in the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment, or PISA, for the first time: Beijing, a municipality, Jiangsu, a province on the eastern coast of the country, and Guangdong, a southern coastal province. -

CHINESE CHEMICAL LETTERS the Official Journal of the Chinese Chemical Society

CHINESE CHEMICAL LETTERS The official journal of the Chinese Chemical Society AUTHOR INFORMATION PACK TABLE OF CONTENTS XXX . • Description p.1 • Impact Factor p.1 • Abstracting and Indexing p.1 • Editorial Board p.1 • Guide for Authors p.6 ISSN: 1001-8417 DESCRIPTION . Chinese Chemical Letters (CCL) (ISSN 1001-8417) was founded in July 1990. The journal publishes preliminary accounts in the whole field of chemistry, including inorganic chemistry, organic chemistry, analytical chemistry, physical chemistry, polymer chemistry, applied chemistry, etc., satisfying a real and urgent need for the dissemination of research results, especially hot topics. The journal does not accept articles previously published or scheduled to be published. To verify originality, your article may be checked by the originality detection service CrossCheck. The types of manuscripts include the original researches and the mini-reviews. The experimental evidence necessary to support your manuscript should be supplied for the referees and eventual publication as Electronic Supplementary Information. The mini-reviews are written by leading scientists within their field and summarized recent work from a personal perspective. They cover many exciting and innovative fields and are of general interest to all chemists. IMPACT FACTOR . 2020: 6.779 © Clarivate Analytics Journal Citation Reports 2021 ABSTRACTING AND INDEXING . Science Citation Index Expanded Chemical Abstracts Chemical Citation Index EDITORIAL BOARD . Editor-in-Chief Xuhong Qian, East China Normal University -

20120619111449-1.Pdf

Organized by: State Key Laboratory of Polymer Physics and Chemistry, China Sponsored by: National Natural Science Foundation of China National Science Foundation, USA Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) Polymer Division, Chinese Chemical Society American Chemical Society Changchun Institute of Applied Chemistry, CAS University of Massachusetts BASF ChiMei ExxonMobil Henkel P&G SABIC Total ORGANIZATION Symposium Chair: Fosong Wang (China) Co-Chairs: Hiroyuki Nishide (Japan), Thomas J. McCarthy (USA), Harm-Anton Klok (Switzerland) International Advisory Committee: Ann-Christine Albertsson, Sweden Caiyuan Pan, China Yong Cao, China Coleen Pugh, USA Geoffrey W. Coates, USA Jiacong Shen, China Jan Feijen, Netherlands Zhiquan Shen, China Zhibin Guan, USA Benzhong Tang, China Charles C. Han, China Gregory N. Tew, USA James L. Hedrick, USA Mitsuru Ueda, Japan Akira Harada, Japan Karen L. Wooley, USA Yoshia Inoue, Japan Deyue Yan, China Ming Jiang, China Qifeng Zhou, China Jung-Il Jin, Korea Xi Zhang, China Timothy E. Long, USA Renxin Zhuo, China Krzysztof Matyjaszewski, USA Organizing Committee: Co-Chairs: Lixiang Wang, Yuesheng Li, Yanhou Geng, Zhaohui Su Members: Xuesi Chen, Yanxiang Cheng, Dongmei Cui, Jianhua Dong, Yanchun Han, Yubin Huang, Jin Ma, Tao Tang, Xianhong Wang, Zhiyuan Xie Secretariat Hui Tong, Guangping Su, Zhihua Ma CONTENTS Schedule overview……………………………………………………..1 Area map……………………………………………………………….2 General information……………………………………………………3 Symposium themes…………………………………………………….4 Program schedule………………………………………………………6 Posters………………………………………………………………...16 -

Sports and Physical Education in China

Sport and Physical Education in China Sport and Physical Education in China contains a unique mix of material written by both native Chinese and Western scholars. Contributors have been carefully selected for their knowledge and worldwide reputation within the field, to provide the reader with a clear and broad understanding of sport and PE from the historical and contemporary perspectives which are specific to China. Topics covered include: ancient and modern history; structure, administration and finance; physical education in schools and colleges; sport for all; elite sport; sports science & medicine; and gender issues. Each chapter has a summary and a set of inspiring discussion topics. Students taking comparative sport and PE, history of sport and PE, and politics of sport courses will find this book an essential addition to their library. James Riordan is Professor and Head of the Department of Linguistic and International Studies at the University of Surrey. Robin Jones is a Lecturer in the Department of PE, Sports Science and Recreation Management, Loughborough University. Other titles available from E & FN Spon include: Sport and Physical Education in Germany ISCPES Book Series Edited by Ken Hardman and Roland Naul Ethics and Sport Mike McNamee and Jim Parry Politics, Policy and Practice in Physical Education Dawn Penney and John Evans Sociology of Leisure A reader Chas Critcher, Peter Bramham and Alan Tomlinson Sport and International Politics Edited by Pierre Arnaud and James Riordan The International Politics of Sport in the 20th Century Edited by James Riordan and Robin Jones Understanding Sport An introduction to the sociological and cultural analysis of sport John Home, Gary Whannel and Alan Tomlinson Journals: Journal of Sports Sciences Edited by Professor Roger Bartlett Leisure Studies The Journal of the Leisure Studies Association Edited by Dr Mike Stabler For more information about these and other titles published by E& FN Spon, please contact: The Marketing Department, E & FN Spon, 11 New Fetter Lane, London, EC4P 4EE. -

The 2010 Asian Games

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln The hinC a Beat Blog Archive 2008-2012 China Beat Archive 7-25-2009 A Reader: The 2010 Asian Games Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/chinabeatarchive Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, Chinese Studies Commons, and the International Relations Commons "A Reader: The 2010 Asian Games" (2009). The China Beat Blog Archive 2008-2012. 432. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/chinabeatarchive/432 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the China Beat Archive at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in The hinC a Beat Blog Archive 2008-2012 by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. A Reader: The 2010 Asian Games July 25, 2009 in The Five-List Plan by The China Beat | No comments The PR folks for the 2010 Asian Games in Guangzhou have added China Beat to their mailing list, so we got their note this week about organizers’ plans to seed clouds to prevent rain during the Games. Our interest was piqued–we hadn’t heard much yet about the 2010 Asian Games. Here are a few of the things we found when we went looking… 1. As with the Olympic preparations in Beijing, there is massive construction, investment, and environmental management (not just cloud- seeding) underway in Guangzhou, according to Xinhua: Authorities are pumping in more than 58 billion yuan (8.5 billion U.S. dollars) to boost the transportation system and protect the environment as Guangzhou, capital of south China’s Guangdong Province, is preparing for the 16th Asian Games next November. -

The 5Th International Conference on Manipulation, Manufacturing and Measurement on the Nanoscale

The 5th International Conference on Manipulation, Manufacturing and Measurement on the Nanoscale 9-13 November 2015, Guangzhou, China 3M-NANO is the annual International Conference on Manipulation, Manufacturing and Measurement on the Nanoscale, which will be held 2015 in Guangzhou, China. The ultimate ambition of this conference series is to bridge the gap between nanosciences and engineering sciences, aiming at emerging market and technology opportunities. The advanced technologies for manipulation, manufacturing and measurement on the nanoscale promise novel revolutionary products and methods in numerous areas of application. All accepted full papers (presented at the conference and following IEEE format) will be included in IEEE Xplore database and indexed by Ei Compendex, upon the approval by IEEE Conference Business Services. Selected outstanding papers will be recommended for publication in the J of Micro-Bio Robotics, Int. J of Nanomanufacturing, Int. J of Intelligent Mechatronics and Robotics, Int. J of Optomechatronics, and other SCI/Ei journals. Organized / Sponsored by: National Natural Science Foundation of China South China University of Technology, China IEEE Nanotechnology Council (technically sponsored) Changchun University of Science and Technology, China University of Oldenburg, Germany Research Center OFFIS, Germany Conference topics include, but are not limited to Nanomanipulation and nanoassembly Self-assembly on the nanoscale Nanomaterials and nanocharacterization Nanometrology Nanohandling robots and systems Precision -

The Business of Sport in China

Paper size: 210mm x 270mm LONDON 26 Red Lion Square London WC1R 4HQ United Kingdom Tel: (44.20) 7576 8000 Fax: (44.20) 7576 8500 E-mail: [email protected] NEW YORK 111 West 57th Street New York The big league? NY 10019 United States Tel: (1.212) 554 0600 The business of sport in China Fax: (1.212) 586 1181/2 E-mail: [email protected] A report from the Economist Intelligence Unit HONG KONG 6001, Central Plaza 18 Harbour Road Wanchai Hong Kong Sponsored by Tel: (852) 2585 3888 Fax: (852) 2802 7638 E-mail: [email protected] The big league? The business of sport in China Contents Preface 3 Executive summary 4 A new playing field 7 Basketball 10 Golf 12 Tennis 15 Football 18 Outlook 21 © Economist Intelligence Unit 2009 1 The big league? The business of sport in China © 2009 Economist Intelligence Unit. All rights reserved. All information in this report is verified to the best of the author’s and the publisher’s ability. However, the Economist Intelligence Unit does not accept responsibility for any loss arising from reliance on it. Neither this publication nor any part of it may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Economist Intelligence Unit. 2 © Economist Intelligence Unit 2009 The big league? The business of sport in China Preface The big league? The business of sport in China is an Economist Intelligence Unit briefing paper, sponsored by Mission Hills China. -

2020 Olympic Games Statistics

2020 Olympic Games Statistics – Women’s HT by K Ken Nakamura The records to look for in Tokyo: 1) Can Wlodarczyk win record third gold? Record (Zhang has three medals) tying third medal? 2) Can US go 1-2? Or even sweep the medal? Summary Page: All time performance list at the Olympics Performance Performer Dist Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 82.29 Anita Wlodarczy k POL 1 Rio de Janeiro 2016 2 77.60 Anita Wlodarczyk 1 London 2012 3 2 77.12 Betty Heidler GER 2 London 2012 4 76.93 An ita Wlodarczyk 1qA Rio de J aneiro 2016 5 3 76.75 Zhang Wenxiu CHN 2 Rio de Janeiro 201 6 6 76.34 Zhang Wenxiu 3 London 2012 7 4 76.05 Kathrin Klaas GER 4 London 2012 Shortest winning distance: 71.16 by Kamila Skolimowska (POL) in 2000 Margin of Victory Difference Winning dist Name Nat Venue Year Max 5.54 82.29 Anita Wlodarczyk POL Rio de Janeiro 2016 1.66m 75.02m Olga Kuzenkova RUS Athinai 2004 Min 48cm 77.60 m Anita Wlodarc zyk POL Lon don 2012 88cm 75.20m Yipsi Moreno CUB Beijing 2008 Longest throw in each round Round distance Name Nat Venue Year Final 82.29 Anita Wlodarczyk POL Rio de Janeiro 2016 qualifying round 76.93 Anita Wlodarczyk POL Rio de Janeiro 201 6 Longest non-qualifier for the final Dist Position Name Nat Venue Ye ar 70.09 7qB Hanna Skydan AZE Rio de Janeiro 2016 69.93 6qA Amber Campbell USA London 2012 Best Marks for Places in the Olympics Pos Distance Name Nat Venue Year 1 82.29 Anita Wlodarczyk POL Rio de Janeiro 2016 2 77.12 Betty Heidler GER London 2012 76.75 Zhang Wenxiu CHN Rio de Janeiro 2016 3 76.34 Zhang Wenxiu CHN London 2012 Last five