The Impact of Recent Policy Revisions Addressing Doping and Gender Rules on Women

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women's 3000M Steeplechase

Games of the XXXII Olympiad • Biographical Entry List • Women Women’s 3000m Steeplechase Entrants: 47 Event starts: August 1 Age (Days) Born SB PB 1003 GEGA Luiza ALB 32y 266d 1988 9:29.93 9:19.93 -19 NR Holder of all Albanian records from 800m to Marathon, plus the Steeplechase 5000 pb: 15:36.62 -19 (15:54.24 -21). 800 pb: 2:01.31 -14. 1500 pb: 4:02.63 -15. 3000 pb: 8:52.53i -17, 8:53.78 -16. 10,000 pb: 32:16.25 -21. Half Mar pb: 73:11 -17; Marathon pb: 2:35:34 -20 ht EIC 800 2011/2013; 1 Balkan 1500 2011/1500; 1 Balkan indoor 1500 2012/2013/2014/2016 & 3000 2018/2020; ht ECH 800/1500 2012; 2 WSG 1500 2013; sf WCH 1500 2013 (2015-ht); 6 WIC 1500 2014 (2016/2018-ht); 2 ECH 3000SC 2016 (2018-4); ht OLY 3000SC 2016; 5 EIC 1500 2017; 9 WCH 3000SC 2019. Coach-Taulant Stermasi Marathon (1): 1 Skopje 2020 In 2021: 1 Albanian winter 3000; 1 Albanian Cup 3000SC; 1 Albanian 3000/5000; 11 Doha Diamond 3000SC; 6 ECP 10,000; 1 ETCh 3rd League 3000SC; She was the Albanian flagbearer at the opening ceremony in Tokyo (along with weightlifter Briken Calja) 1025 CASETTA Belén ARG 26y 307d 1994 9:45.79 9:25.99 -17 Full name-Belén Adaluz Casetta South American record holder. 2017 World Championship finalist 5000 pb: 16:23.61 -16. 1500 pb: 4:19.21 -17. 10 World Youth 2011; ht WJC 2012; 1 Ibero-American 2016; ht OLY 2016; 1 South American 2017 (2013-6, 2015-3, 2019-2, 2021-3); 2 South American 5000 2017; 11 WCH 2017 (2019-ht); 3 WSG 2019 (2017-6); 3 Pan-Am Games 2019. -

AT-HT-W-F--A--.RS1.Pdf

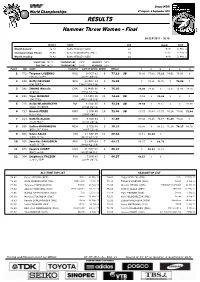

Daegu (KOR) World Championships 27 August - 4 September 2011 RESULTS Hammer Throw Women - Final 04 SEP 2011 - 18:15 RESULT NAME AGE VENUE DATE World Record 79.42 Betty HEIDLER (GER) 28 Halle 21 May 11 Championships Record 77.96 Anita WLODARCZYK (POL) 24 Berlin 22 Aug 09 World Leading 79.42 Betty HEIDLER (GER) 28 Halle 21 May 11 START TIME 18:10 TEMPERATURE 28°C HUMIDITY 54% END TIME 19:37 TEMPERATURE 27°C HUMIDITY 54% PLACE BIB NAME COUNTRY DATE OF BIRTH ORDER RESULT 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 772 Tatyana LYSENKO RUS 9 OCT 83 6 77.13 SB 76.80 77.09 77.13 74.51 75.05 X 타티아나 리센코 1983년 10월 9일 2 420 Betty HEIDLER GER 14 OCT 83 3 76.06 X 73.96 74.70 X 76.06 X 베티 하이들러 1983년 10월 14일 3 246 ZHANG Wenxiu CHN 22 MAR 86 4 75.03 75.03 74.31 X 73.17 71.86 74.79 장 웬시우 1986년 3월 22일 4 285 Yipsi MORENO CUB 19 NOV 80 12 74.48 SB 73.29 X 74.48 X X X 입시 모레노 1980년 11월 19일 5 715 Anita WLODARCZYK POL 8 AUG 85 8 73.56 SB 73.56 X 72.61 X X 72.65 아니타 볼다르치크 1985년 8월 8일 6 733 Bianca PERIE ROU 1 JUN 90 10 72.04 SB 67.73 70.40 67.75 70.24 70.91 72.04 비앙카 페리 1990년 6월 1일 7 424 Kathrin KLAAS GER 8 FEB 84 1 71.89 67.02 70.18 70.67 71.89 70.44 X 카트린 클라스 1984년 2월 8일 8 650 Zalina MARGHIEVA MDA 5 FEB 88 5 70.27 69.99 X 68.13 70.24 70.27 68.76 잘리나 마르기에바 1988년 2월 5일 9 506 Silvia SALIS ITA 17 SEP 85 11 69.88 68.61 69.88 X 실비아 살리스 1985년 9월 17일 10 105 Jennifer DAHLGREN ARG 21 APR 84 7 69.72 68.27 X 69.72 헤니퍼 달그렌 1984년 4월 21일 11 928 Jessica COSBY USA 31 MAY 82 9 68.91 X 68.91 68.15 제시카 코스비 1982년 5월 31일 12 364 Stéphanie FALZON FRA 7 JAN 83 2 66.57 66.57 X X 스테파니 팔존 1983년 1월 7일 ALL-TIME TOP LIST -

China's Sports Heroes: Nationalism, Patriotism, and Gold Medal

The International Journal of the History of Sport ISSN: 0952-3367 (Print) 1743-9035 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fhsp20 China’s Sports Heroes: Nationalism, Patriotism, and Gold Medal Lu Zhouxiang & Fan Hong To cite this article: Lu Zhouxiang & Fan Hong (2019) China’s Sports Heroes: Nationalism, Patriotism, and Gold Medal, The International Journal of the History of Sport, 36:7-8, 748-763, DOI: 10.1080/09523367.2019.1657839 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2019.1657839 Published online: 30 Sep 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 268 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fhsp20 THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF THE HISTORY OF SPORT 2019, VOL. 36, NOS. 7–8, 748–763 https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2019.1657839 China’s Sports Heroes: Nationalism, Patriotism, and Gold Medal Lu Zhouxianga and Fan Hongb aSchool of Modern Languages, Literatures and Cultures, National University of Ireland, Maynooth, Ireland; bThe University of Bangor, Bangor, UK ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Sport has been of great importance to the construction of China; hero; politics; Chinese national consciousness during the past century. This art- nationalism; icle examines how China’s sport celebrities have played their part sports patriotism in nation building and identity construction. It points out that Chinese athletes’ participation in international sporting events in the first half of the twentieth century demonstrated China’s motivation to stay engaged with the world, and therefore led to their being regarded as national heroes. -

2020 Olympic Games Statistics

2020 Olympic Games Statistics – Women’s HT by K Ken Nakamura The records to look for in Tokyo: 1) Can Wlodarczyk win record third gold? Record (Zhang has three medals) tying third medal? 2) Can US go 1-2? Or even sweep the medal? Summary Page: All time performance list at the Olympics Performance Performer Dist Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 82.29 Anita Wlodarczy k POL 1 Rio de Janeiro 2016 2 77.60 Anita Wlodarczyk 1 London 2012 3 2 77.12 Betty Heidler GER 2 London 2012 4 76.93 An ita Wlodarczyk 1qA Rio de J aneiro 2016 5 3 76.75 Zhang Wenxiu CHN 2 Rio de Janeiro 201 6 6 76.34 Zhang Wenxiu 3 London 2012 7 4 76.05 Kathrin Klaas GER 4 London 2012 Shortest winning distance: 71.16 by Kamila Skolimowska (POL) in 2000 Margin of Victory Difference Winning dist Name Nat Venue Year Max 5.54 82.29 Anita Wlodarczyk POL Rio de Janeiro 2016 1.66m 75.02m Olga Kuzenkova RUS Athinai 2004 Min 48cm 77.60 m Anita Wlodarc zyk POL Lon don 2012 88cm 75.20m Yipsi Moreno CUB Beijing 2008 Longest throw in each round Round distance Name Nat Venue Year Final 82.29 Anita Wlodarczyk POL Rio de Janeiro 2016 qualifying round 76.93 Anita Wlodarczyk POL Rio de Janeiro 201 6 Longest non-qualifier for the final Dist Position Name Nat Venue Ye ar 70.09 7qB Hanna Skydan AZE Rio de Janeiro 2016 69.93 6qA Amber Campbell USA London 2012 Best Marks for Places in the Olympics Pos Distance Name Nat Venue Year 1 82.29 Anita Wlodarczyk POL Rio de Janeiro 2016 2 77.12 Betty Heidler GER London 2012 76.75 Zhang Wenxiu CHN Rio de Janeiro 2016 3 76.34 Zhang Wenxiu CHN London 2012 Last five -

Asia-Top10-2014

A S I A N A T H L E T I C S TOP 10 R A N K I N G S 2 0 1 4 - compiled by Heinrich Hubbeling, ASIAN AA Statistician - M E N e v e n t s 100 m / automatic timing 9.93 +0.4 AR Femi Seun Ogunode QAT 150591 1 Incheon 28.09.14 10.05 +1.6 AJR Yoshihide Kiryu JPN 151295 1rA Kumagaya 17.05.14 10.10 +0.4 Su Bingtian CHN 290889 2 Incheon 28.09.14 10.13 +0.7 Kei Takase JPN 251188 1 Hiroshima 29.04.14 10.14 +0.1 Ryota Yamagata JPN 100692 1s2 Kumagaya 05.09.14 10.17 +0.2 Zhang Peimeng CHN 130387 3s2 Incheon 28.09.14 10.21 +1.6 Asuka Cambridge JPN 310593 2rA Kumagaya 17.05.14 10.22 +1.1 Hasan Taftian IRI 040593 1 Almaty 14.06.14 10.22 +1.8 Yusuke Kotani JPN 230989 1r2 Fuse 29.06.14 10.22 +1.0 Pan Xinyue CHN 170193 1 Jinhua 06.07.14 irregular auto-timing 10.08 +1.7 Jirapong Meenapra THA 110593 1h3 Nakhon Ratchas. 11.12.14 wind-aided 10.08 +2.7 Zhang Peimeng CHN 130387 7 Eugene 31.05.14 10.10 +3.4 Sota Kawatsura JPN 190689 1 Austin 29.03.14 10.19 +3.0 Takuya Kawakami JPN 080695 1h3 Taipei 12.06.14 10.20 +2.2 Reza Ghasemi IRI 240787 1 Oordegem 05.07.14 10.21 +3.4 Yuki Koike JPN 130595 3 Austin 29.03.14 10.22 +2.6 Samuel Francis QAT 270387 1 Plovdiv 12.07.14 200 m / automatic timing 20.06 +1.7 Femi Seun Ogunode QAT 150591 1 Sofia 28.06.14 20.34 +1.7 Kei Takase JPN 251188 1h3 Fukuroi 03.05.14 20.39 +0.8 Shota Iizuka JPN 250691 1rA Fukuroi 03.05.14 20.41 0.0 Shota Hara JPN 180792 1 Yokohama 25.05.14 20.44 +1.8 Masafumi Naoki JPN 191193 1h4 Fukuroi 03.05.14 20.44 -0.3 NR Xie Zhenye CHN 170893 1 Suzhou 11.10.14 20.45 +0.6 Kotaro Taniguchi JPN 031194 1rB Fukuroi -

2011 Asian Championships Statistics – Women's HT

2011 Asian Championships Statistics – Women’s HT Only Chinese Hammer throwers have won Asian Championships in this event. Can Masumi Aya break their dominance? All time performance list at the Asian Championships Performance Performer Distance Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 72.07 Zhang Wenxiu CHN 1 Guangzhou 2009 2 2 71.10 Gu Yuan CHN 1 Colombo 2002 3 70.78 Gu Yuan 1 Manila 2003 4 70.05 Zhang Wenxiu 1 Incheon 2005 5 3 66.66 Liu Yinghui CHN 2 Manila 2003 6 4 65.87 Hao Shuai CHN 2 Guangzhou 2009 7 5 64.04 Masumi Aya JPN 3 Manila 2003 8 63.89 Gu Yuan 2 Incheon 2005 9 6 62.62 Yuka Murofushi 3 Incheon 2005 10 61.99 Yuka Murofushi 3 Guangzhou 2009 11 61.86 Gu Yuan 1 Fukuoka 1998 12 7 60.58 Liao Xiaoyan CHN 1 Amman 2007 13 8 59.66 Huang Chih-Feng TPE 4 Incheon 2005 14 9 59.40 Chisato Ohashi JPN 5 Incheon 2005 15 59.31 Huang Chih-Feng 4 Manila 2003 16 10 59.02 Li Xiaoxue CHN 1 Djakarta 2000 Margin of Victory Difference Winning Distance Name Nat Venue Year Max 12.91m 71.10m Gu Yuan CHN Colombo 2002 Min 38cm 59.02m Li Xiaoxue CHN Djakarta 2000 Best Marks for Places in the Asian Championships Pos Distance Name Nat Venue Year 1 72.07 Zhang Wenxiu CHN Guangzhou 2009 2 66.66 Liu Yinghui CHN Manila 2003 3 64.04 Masumi Aya JPN Manila 2003 4 59.66 Huang Chih-Feng TPE Incheon 2005 5 59.40 Chisato Ohashi JPN Incheon 2005 Multiple Medalists: Zhang Wenxiu (CHN): 2005, 2009 Gu Yuan (CHN): 1998, 2002, 2003, Number of Medals by Countries: Nation Gold Silver Bronze CHN 7 3 JPN 2 5 TPE 1 1 KOR 1 IND 1 Multiple Medals by athletes from a single nation Nation Year Gold -

2016 Olympic Games Statistics – Women's HT

2016 Olympic Games Statistics – Women’s HT by K Ken Nakamura The records to look for in Rio de Janeiro: Olympic record, largest winning margin, and longest throw in Rio are all under threat by Wlodarczyk Summary Page: All time performance list at the Olympics Performance Performer Dist Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 78.18 Tatyana Beloborodova Lysenko RUS 1 London 2012 2 2 77.60 Anita Wlodarczyk POL 2 London 2012 3 3 77.12 Betty Heidler GER 3 London 2012 4 4 76.34 Aksana Miankova BLR 1 Beijing 2008 4 4 76.34 Zhang Wenxiu CHN 4 London 2012 6 6 76.05 Kathrin Klaas GER 5 London 2012 Shortest winning distance: 71.16 by Kamila Skolimowska (POL) in 2000 Margin of Victory Difference Winning dist Name Nat Venue Year Max 1.66m 75.02m Olga Kuzenkova RUS Athinai 2004 Min 58cm 78.18m Tatyana Lysenko RUS London 2012 1.14m 76.34m Aksana Miankova BLR Beijing 2008 Longest throw in each round Round distance Name Nat Venue Year Final 78.18 Tatyana Lysenko RUS London 2012 qualifying round 75.68 Anita Wlodarczyk POL London 2012 Longest non-qualifier for the final Dist Position Name Nat Venue Year 69.93 6qA Amber Campbell USA London 2012 Best Marks for Places in the Olympics Pos Distance Name Nat Venue Year 1 78.18 Tatyana Lysenko RUS London 2012 76.34 Aksana Miankova BLR Beijing 2008 2 77.60 Anita Wlodarczyk POL London 2012 75.20 Yipsi Moreno CUB Beijing 2008 3 77.12 Betty Heidler GER London 2012 74.32 Zhang Wenxiu CHN Beijing 2008 4 76.34 Zhang Wenxiu CHN London 2012 Multiple Medalists: Yipsi Moreno (CUB): 2004 Silver, 2008 Silver Olga Kuzenkova (RUS): 2000 -

USATF Press Officers in Moscow Susan Hazzard, Director of Public Relations Russia Cell: +79259227134 Email: [email protected]

2013 IAAF World Championships Team USA Media Kit – Track & Field TABLE OF CONTENTS World Team Announcement. ................................................................ 2 Roster by state ..................................................................................3-5 Roster by Event .................................................................................6-7 Alphabetical Roster with Twitter handles ..........................................8-9 All-Time Team USA World Championships medal tables ................. 10 Team USA World Championships medal breakdown ...................11-14 Best Marks by Team USA at the World Championships .................... 15 Team Staff .....................................................................................16-17 World Records. ............................................................................. 18-21 American Records .........................................................................22-27 USATF Press Officers in Moscow Susan Hazzard, Director of Public Relations Russia Cell: +79259227134 Email: [email protected] Katie Branham, Communications and Marketing Manager Russia Cell: +79257615458 Email: [email protected] 1 Team USA Named for World Championships in Moscow INDIANAPOLIS - Nine reigning World champions and 20 individual Olympic medalists from London will lead Team USA at the IAAF World Championships in Moscow, Russia from August 10-18. This year’s roster features a mix of veteran athletes with a large class of newcomers to the senior world stage. -

Press Release GENDERS ENGENDER

! GENDERS ENGENDER 2018.3.22 - 2018.5.19 Opening 2018.3.22 16:00 ARTISTS AND PARTICIPANTS: HUANG Jingyuan, LI Shuang, United Motion, MA Qiusha, Xiaoshi Vivian Vivian QIN, Mountain River Jump!, Writing Mothers Working Group (WMWG), ZHANG Ran, ZHANG Sirui SPACE DESIGNER: LI Juchuan READING LIST: Folded Room CURATOR: LI Jia ARTISTIC DIRECTOR: TANG Xin Red No.1-B2, Caochangdi, Cuigezhuang, Chaoyang District, Beijing, CHINA www.taikangspace.com 10:30 - 17:30, Tuesday to Saturday About Exhibition Taikang Space will present “Genders Engender”, a major exhibition of the year, accompanied by forums, workshops and publications altogether. Focusing on gender studies and practices that take place nowadays or have impacts on social recognition of gender disparity, it attempts to create a platform for display, a space for conversation, even a workshop for production for these plural discourses through curating an exhibition. It embraces and welcomes participants from every field and every community, expecting to open up a broader sight of view, to build up more diverse connections. “Genders Engender” is not an exhibition presenting “feminist art” or “art of the women artists”, nor providing any definition or producing the tags based on any essentialist tendencies. We believe that gender identity is a kind of symptom or phenomenon which requires reading and interpreting rather than the cause or standard. It is not the similarity of the temperament, the theme or the method that link these works and performances together. On the contrary, the inner connection among the exhibition is a gender perspective that has been already integrated into the practice of all the exhibition participants. -

Asian Athletics Ranking 2019

ASIAN athletics 2 0 1 9 R a n k i n g s compiled by: Heinrich Hubbeling - ASIAN AA Statistician – 0 C o n t e n t s Page 1 Table of Contents/Abbreviations for countries 2 - 3 Introduction/Details 4 - 9 Asian Continental Records 10 - 57 2019 Rankings – Men events 58 Name changes (to Women´s Rankings) 59 - 104 2019 Rankings – Women events & Mixed 4x400 m 105 – 107 Asian athletes in 2019 World lists 108 – 110 Contacts for other publications etc. ============================================================== Abbreviations for countries (as used in this booklet) AFG - Afghanistan KGZ - Kyrghizstan PLE - Palestine BAN - Bangladesh KOR - Korea (South) PRK - D P R Korea BHU - Bhutan KSA - Saudi Arabia QAT - Qatar BRN - Bahrain KUW - Kuwait SGP - Singapore BRU - Brunei LAO - Laos SRI - Sri Lanka CAM - Cambodia LBN - Lebanon SYR - Syria CHN - China MAC - Macau THA - Thailand HKG - Hongkong MAS - Malaysia TJK - Tajikistan INA - Indonesia MDV - Maldives TKM - Turkmenistan IND - India MGL - Mongolia TLS - East Timor IRI - Iran MYA - Myanmar TPE - Chinese Taipei IRQ - Iraq NEP - Nepal UAE - United Arab E. JOR - Jordan OMA - Oman UZB - Uzbekistan JPN - Japan PAK - Pakistan VIE - Vietnam KAZ - Kazakhstan PHI - Philippines YEM - Yemen ============================================================== Cover Photo: SALWA EID NASER -Gold medal at World Champs with Asian Record (48.14 seconds, 3rd in All-Time Rankings and fastest time since 1985) -Winner of Diamond League 400 m final -4 Gold medals at Asian Champs (200 m/400 m/4x400 m & Mixed Relay) 1 I n t r o d u c t i o n With this booklet I present my 31st consecutive edition of Asian athletics statistics. -

AAAAC-16-Incheon-2005

Asian Athletics Association Results ACC 2005 16th Asian Athletics Championships 1500 M. Incheon - 2005 1. Kamal Abubakar Ali QAT 3:44.24 2. T Agar Adian IRQ 3:44.57 MEN 3. Kareem Nasser Shams QAT 3:46.09 4. Murakami Yasunori JPN 3:46.80 100 M. 5. Kolganov Mikhail KAZ 3:47.45 6. Chaminda Wijekoon SRI 3:48.29 1. Al Ghes Yahya KSA 10.39 7. Ram Ghamanda IND 3:49.62 2. Suetsugu Shingo JPN 10.42 8. Sunil Jayaseera SRI 3:50.05 3. Al-Obaidli Khalid Yousuf QAT 10.45 4. Nobuharu Asahara JPN 10.57 5. Sondee Wachara THA 10.61 5000 M. 6. Anil Kumar IND 10.61 1. Kurui James Kwalia QAT 14:08.56 7. Vitality Medvedev KAZ 10.67 2. Bashair Daham Najm QAT 14:15.92 Muravyev Vyacheslav KAZ DNS 3. Wu Wen Chien TPE 14:32.43 Wind - 0.3 4. Seto Tomohiro JPN 14:32.77 5. Srisung Boonthung THA 14:32.85 200 M. 6. Maeda Takashi JPN 14:33.18 7. Bagrer Denis KGZ 14:34.69 1. Al-Bishi Hamed HA KSA 20.66 8. Amirov Ajmal TJK 14:43.29 2. Tatsuro Yoshino JPN 20.68 3. Yang Yaosu CHN 20.85 10000 M. 4. Tan Yik Chuan HKG 21.01 5. Prasanna Amarasekara SRI 21.12 1. Rashed Essa Ismail QAT 29:03.60 6. Wang Chengilang CHN 21.29 2. Al Otaibi Mukhlid KSA 29:04.85 7. Al-Delhmi Hamood OMN 21.31 3. Sedam Ali Dawoud QAT 29:05.93 8. -

A S I a N a T H L E T I C S Top 10 R a N K I N G S 2 0 1 5 M E N

A S I A N A T H L E T I C S TOP 10 R A N K I N G S 2 0 1 5 - compiled by Heinrich Hubbeling, ASIAN AA Statistician - M E N e v e n t s 100 m / automatic timing 9.91 +1.8 AR Femi Seun Ogunode QAT 150591 1 Wuhan 04.06.15 9.99 +1.5 NR Su Bingtian CHN 290889 3 Eugene 30.05.15 10.09 -0.1 Kei Takase JPN 251188 2 Kawasaki 10.05.15 10.09 +0.3 Yoshihide Kiryu JPN 151295 1 Fuse 18.10.15 10.10 +0.4 NR Hasan Taftian IRI 040593 1 Almaty 25.07.15 10.12 +0.4 Reza Ghasemi IRI 240787 2 Almaty 25.07.15 10.13 -0.3 Zhang Peimeng CHN 130387 5h3 Beijing 22.08.15 10.16 +1.8 NR Kim Kuk-Young KOR 190491 2s1 Gwangju 09.07.15 10.16 +1.7 NR Barakat M. Al-Harthi OMA 150688 1 Mungyeong 06.10.15 10.19 +0.4 Takuya Nagata JPN 140694 1 Hiratsuka 14.06.15 wind-aided 9.87 +3.3 Yoshihide Kiryu JPN 151295 1 Austin 28.03.15 10.05 +4.1 Barakat M. Al-Harthi OMA 150688 2 Manama 25.04.15 10.06 Meshal Khalifa Al-Mutairi KUW 160397 1h1 Manama 25.04.15 10.14 +3.2 Kenji Fujimitsu JPN 010586 1 Heusden 18.07.15 10.15 +3.3 Ryota Yamagata JPN 100692 7 Austin 28.03.15 200 m / automatic timing 19.97 -0.4 AR Femi Seun Ogunode QAT 150591 1 Bruxelles 11.09.15 20.13 +0.6 Kenji Fujimitsu JPN 010586 3rB Luzern 14.07.15 20.14 +1.0 Kei Takase JPN 251188 1 Kumagaya 17.05.15 20.34A -0.4 Abdul Hakim Sani Brown JPN 060399 1 Cali 19.07.15 20.42 +1.4 Shota Iizuka JPN 250691 1h3 Niigata 26.06.15 20.47 +0.4 NR Moh.