The Capitoline Wolf: Fakes and Forgeries in the Ancient World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 5 Art Offers a Glimpse at a Different World Than That Which The

chapter 5 Art Art offers a glimpse at a different world than that which the written narratives of early Rome provide. Although the producers (or rather, the patrons) of both types of work may fall into the same class, the educated elite, the audience of the two is not the same. Written histories and antiquarian works were pro- duced for the consumption of the educated; monuments, provided that they were public, were to be viewed by all. The narrative changes required by dyadic rivalry are rarely depicted through visual language.1 This absence suggests that the visual narratives had a different purpose than written accounts. To avoid confusion between dyadic rivals and other types of doubles, I con- fine myself to depictions of known stories, which in practice limits my inves- tigation to Romulus and Remus.2 Most artistic material depicting the twins comes from the Augustan era, and is more complimentary than the literary narratives. In this chapter, I examine mainly public imagery, commissioned by the same elite who read the histories of the city. As a result, there can be no question of ignorance of this narrative trope; however, Roman monuments are aimed at a different and wider audience. They stress the miraculous salvation of the twins, rather than their later adventures. The pictorial language of the Republic was more interested in the promo- tion of the city and its elite members than problematizing their competition. The differentiation between artistic versions produced for an external audi- ence and the written narratives for an internal audience is similar to the dis- tinction made in Propertius between the inhabitants’ knowledge of the Parilia and the archaizing gloss shown to visitors. -

3. Etruscans Romans

The Etruscans 8th to the 5th century B.C (900/700-500 B.C) Triclinium – formal dining room Interior of the Tomb of the Triclinium, from the Monterozzi necropolis, Tarquinia, Italy, ca. 480–470 BCE Italy in Etruscan times Important sites: Tarquinia Cerveteri Vulci Villanova Brief History • The Etruscans occupied the region to the north of Rome, in what is today known as Tuscany (Central). • The Romans (still considered a tribe, yet the Empire it would become) were first a subject people of the Etruscans and later their conquerors. • The Etruscan culture was well-developed and advanced but distinctively different from the cultures of the other peoples in the region. This distinctive difference immediately led to the question of “where did the Etruscans originate?” Where did the Etruscans originate? • Some Greeks held that the Etruscans came from Lydia, a kingdom of western Anatolia (or modern day Turkey). • In the 19th c, it was discovered that most of the languages of Europe belonged to one big language family called Indo- European but Etruscan was not one of them. – The Etruscan language is unique in the ancient Greco- Roman world. There are no known parent languages to Etruscan, nor are there any modern descendants. As Romans took control, Latin became the dominant language. – We have no surviving histories or literature in Etruscan. Science vs. Art • The American Journal of Human • Villanovan Culture: 900-700 BC. Genetics reports finding 11 A culture of Northern Italy, they lineages of human mitochondrial were first identified by their DNA in Tuscany that occur in the cemeteries. -

From Seven Hills to Three Continents: the Art of Ancient Rome 753 BCE – According to Legend, Rome Was Founded by Romulus and Remus

From Seven Hills to Three Continents: The Art of Ancient Rome 753 BCE – According to legend, Rome was founded by Romulus and Remus. According to Virgil, Romulus and Remus were descendants of Aeneas, son of Aphrodite. Capitoline Wolf, from Rome, Italy, ca. 500–480 BCE. Bronze, approx. 2’ 7 1/2” high. Palazzo dei Conservatori, Rome. The Great Empire: The Republic of Rome http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yvsbfoKgG-8 The Roman Republic (Late 6th – 1st c. BCE) 509 BC- Expulsion of the Etruscan Kings and establishment of the Roman Republic 27 BC – End of the Republic - Augustus Becomes the First Emperor of Rome This formula is referring to the government of the Roman Republic, and was used as an official signature of the government. Senatus Populusque Romanus "The Roman Senate and People“ The Roman constitution was a republic in the modern sense of the word, in that the supreme power rested with the people; and the right to take part in political life was given to all adult male citizens. Although it was thus nominally a democracy in that all laws had to be approved by an assembly of citizens, the republic was in fact organized as an aristocracy or broad based oligarchy, governed by a fairly small group of about fifty noble families. Sculpture Roman with Busts of Ancestors 1st c. BCE-1st c. CE Roman Republican sculpture is noted for its patrician portraits employing a verism (extreme realism) derived from the patrician cult of ancestors and the practice of making likenesses of the deceased from wax death-masks. -

Roman Myth As History -‐ Monarchy to Republic

The Roman World Roman Myth as History - Monarchy to Republic Terminology • BCE - Before the Common Era • CE - Common Era Now: 30th July, 2013 CE Caesar murdered: Ides (15th) March, 44 BCE ROME’S SEVEN HILLS! " • Palane Hill • Roman Forum • River Tiber http://www.laits.utexas.edu/moore/rome/image/map-early-rome Ethnic Groups of Ancient Italy Early Romans trade with •Etruscans •Oscans •Latins •Greeks Similar image http:// at - http://www.utexas.edu/courses/romanciv/romancivimages3/Italymap.jpgSiwww.orbilat.com/Maps/Latin/ Origins of Rome • MYTH: Rome founded 753 BCE (8th c.)! • ARCHAEOLOGY: Iron Age settlements - 9th c.BCE" • hRp://www.utexas.edu/courses/ Reconstruction of Iron Age huts on Palatine Hill (based on evidence of excavation) http://ancientrome.ru/art/artworken/img.htm?id=72 ‘Capitoline Wolf’ (Capitoline Museum, Rome) bronze wolf ?5th c.BCE; babies added 15th c.CE hp://schools.nashua.edu/myclass/lavalleev/Art%20History%20Pictures/ch09/9-10.jpg Romulus and Remus! • mythic narrative • Mars • Rhea Silvia (Ilia) - Vestal virgin • Amulius - uncle of Rhea Silvia • Numitor - father of Rhea Silvia • twin boys cast adrift on River Tiber Statue of Mars, Roman god of war, early 4th c., Yorkshire Museum http://www.flickr.com/photos/carolemage/7684918728/lightbox/ Romulus and Remus! • mythic narrative • Mars • Rhea Silvia (Ilia) • Numitor - father of Rhea Silvia - king • Amulius - uncle of Rhea Silvia • twin boys cast adrift on River Tiber • come ashore at Lupercal near Palatine • raised by she-wolf (lupa) • foster mother Larentia => lupa -

I Give Permission for Public Access to My Honors Paper and for Any

I give permissionfor public accessto my Honorspaper and for any copying or digitizationto be doneat the discretionof the CollegeArchivist and/orthe ColleseLibrarian. fNametyped] MackenzieSteele Zalin Date G-rr.'. 1 30. zoal Monuments of Rome in the Films of Federico Fellini: An Ancient Perspective Mackenzie Steele Zalin Department of Greek and Roman Studies Rhodes College Memphis, Tennessee 2009 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Arts degree with Honors in Greek and Roman Studies This Honors paper by Mackenzie Steele Zalin has been read and approved for Honors in Greek and Roman Studies. Dr. David H. Sick Project Sponsor Dr. James M. Vest Second Reader Dr. Michelle M. Mattson Extra-Departmental Reader Dr. Kenneth S. Morrell Department Chair Acknowledgments In keeping with the interdisciplinary nature of classical studies as the traditional hallmark of a liberal arts education, I have relied upon sources as vast and varied as the monuments of Rome in writing this thesis. I first wish to extend my most sincere appreciation to the faculty and staff of the Intercollegiate Center for Classical Studies in Rome during the spring session of 2008, without whose instruction and inspiration the idea for this study never would have germinated. Among the many scholars who have indelibly influenced my own study, I am particularly indebted to the writings of Catherine Edwards and Mary Jaeger, whose groundbreaking work on Roman topography and monuments in Writing Rome: Textual approaches to the city and Livy’s Written Rome motivated me to apply their theories to a modern context. In order to establish the feasibility and pertinence of comparing Rome’s antiquity to its modernity by examining their prolific juxtapositions in cinema as a case study, I have also relied a great deal upon the works of renowned Italian film scholar, Peter Bondanella, in bridging the ages. -

Gardner's Art Through the Ages

Gardner’s Art through the Ages Chapters 6-7 The Etruscans and The Roman Empire 1 Italy - Etruscan Period 2 Sarcophagus with reclining couple, from the Banditaccia necropolis, Cerveteri, Italy, ca. 520 BCE. Painted terracotta, 3’ 9 1/2” X 6’ 7”. Museo Nazionale di Villa Giulia, Rome. Note the archaic smile. Made with the coiling method. Women had more freedom in Etruscan society and had more rights than in Greece. Educaton was more available and they could own property. 3 Tumuli (Earthen covered mounds) in the Banditaccia necropolis, Cerveteri, Italy, seventh to second centuries BCE. These tombs often housed many generations of family members with earthly objects like furniture, kitchen utensils, mirrors, murals of life on Earth. 4 Interior of the Tomb of the Leopards, Tarquinia, Italy, ca. 480–470 BCE. 5 Interior of the Tomb of the Augurs, Monterozzi necropolis, Tarquinia, Italy, ca. 520 BCE. 6 Figure 6-12 Capitoline Wolf, from Rome, Italy, ca. 500–480 BCE. Bronze, 2’ 7 1/2” high. Musei Capitolini, Rome. The two infants are 15th Century additions, Romulus and Remus. 7 Arch construction started in the late Etruscan period, but flourished in ancient Rome. Key words: Voussoirs, keystone and crown 8 The Roman World 9 ROMAN ART • Roman architecture contributed to the expanse of the Roman Empire. • Much of Roman art and architecture communicates ideas of power for the emperor and empire. • Many of the changes in Roman art and architecture came as a result of expansion of the Roman Empire and the incorporation of the conquered cultures. • The Romans took over Greece in 146 BCE. -

Ancient Roman Munificence: the Development of the Practice and Law of Charity

Texas A&M University School of Law Texas A&M Law Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 3-2004 Ancient Roman Munificence: The Development of the Practice and Law of Charity William H. Byrnes IV Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation William H. Byrnes IV, Ancient Roman Munificence: The Development of the Practice and Law of Charity, 57 Rutgers L. Rev. 1043 (2004). Available at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar/421 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Texas A&M Law Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Texas A&M Law Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANCIENT ROMAN MUNIFICENCE: THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE PRACTICE AND LAW OF CHARITY William H. Byrnes, IV* INTRODUCTION This article traces Roman charity from its incipient meager beginnings during Rome's infancy to the mature legal formula it assumed after intersecting with the Roman emperors and Christianity. During this evolution, charity went from being a haphazard and often accidental private event to a broad undertaking of public, religious, and legal commitment. To mention the obvious, Rome was the greatest and most influential empire in the ancient world. It lasted more than a thousand years, traditionally beginning in 753 B.C. as a kingdom under Romulus.' In 509 B.C. it became a republic with permanent tyranny beginning in 31 B.C. under direction of the immortal Julius Caesar.2 The exact date of the end of * Professor and Director, Walter H. -

Lecture 10 Ancient Rome WC 159-172 PP 156-161: the XII

Lecture 10 Ancient Rome WC 159-172 PP 156-161: The XII Tables Chronology: Roman Republic 509-31 BCE Roman Empire 31 BCE- 1453 CE ~1000 BCE Villanova culture in Italy 31 BCE Battle of Actium 753 Rome founded by Romulus and Remus 27 Octavian becomes “Augustus” 700-509 Etruscans dominate Tiber Valley 27 BCE-231 CE Principate 509 Rome becomes a Republic 231-311 Dominate 275 Rome conquers all Italy 312 Constantine becomes Emperor 145 Rome conquers all Mediterranean 330 capital of empire moved to Constantinople 44 Julius Caesar assassinated 476 Western empire “falls” Star Terms Geog. Terms: Romulus and Remus • Italy Rape of Lucretia • Etruria Etruscans • Latium fasces • Rome Pax Romana A. Capitoline Wolf, From Etruria 500-480 BCE about 33 ½ inches; hollow-cast bronze, Capitoline Museum, Rome The she-wolf from the legend of Romulus and Remus was regarded as a symbol of Rome from ancient times. Several ancient sources refer to statues depicting the wolf suckling the twins. Pliny the Elder mentions the presence in the Roman Forum of a statue of a she-wolf. Although this statue has become symbolic of the founding of Rome, the original Etruscan statue probably had nothing to do with that legend. The bronze figures of the twins, representing the founders of the city of Rome, were added in the late 15th century. The significance of this image is that is gives form to the mythic origins of Rome, especially those reported by Livy and Vergil in their accounting for how Rome became such a large and successful empire. Lecture 10 Ancient Rome B. -

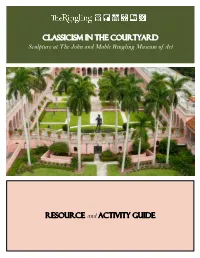

CLASSICISM in the COURTYARD RESOURCE and ACTIVITY GUIDE

Classicism in the Courtyard Sculpture at The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art Resource and activity guide Welcome, Educators! This guide is designed to introduce you and your Contents students to the fascinating history behind the bronze and stone sculptures that populate the courtyard of The Ringling Museum of Art. The activity ideas and Welcome, Educators! 2 accompanying resources provided here will get your students thinking about the many lives these About the Courtyard Sculptures 2 sculptures have had, from their original creation during ancient times, to their popularity during the Looking at Sculptures 3-6 As Original Works of Art Renaissance, to their widespread familiarity and acclaim during more recent centuries. We hope you Looking at Sculptures 7-10 will find these materials useful, and that you will As Copies and Adaptations adapt and build on them to suit your needs. Looking at Sculptures 11-12 As Sources of Inspiration About the Courtyard Sculptures Looking at Sculptures 13-14 Before and during construction of The Ringling As Public Art Museum of Art in the late 1920s, John Ringling collected more than fifty bronze casts of famous Appendix 15-20 classical and Renaissance sculptures. He ordered them from the renowned Chiurazzi Foundry in Emotion in Art worksheet 16 Naples, Italy, a firm that had secured rare molds of Ideal / Real worksheet 17 famous works from the Vatican collections and from the archeological sites of Pompeii and Herculaneum. Contrasting Opinions on Copies sheet 18 The bronze used for these copies, made from 90% copper and 10% tin, was cast using the ancient lost- Image Credits 19 wax process. -

The New Galleries of Ancient Classical Art Open

VOLUME: 8SUMMER 2007 The New Galleries between 1912 and 1926. The atrium, which was designed to evoke the garden of alarge of Ancient Classical Art privateRoman villa, has been enlarged, and Open at the in spite of its numerous innovations, the new design remains faithful to the original Metropolitan architectural concept: aspace designed ac- cordingtoastyle influenced by Classical Museum, New York architecture and roofed in glass, which al- by Jane Whitehead and Larissa lows the viewer to admire the objects under Bonfante natural light.” This is the space formerly occupied by the kitchen and restaurant, put The Metropolitan Museum’sopening of in place by aformer director,Francis Henry the new galleries of ancient Hellenistic, Etr- Taylor; the huge windows in the south wall, uscan, and Roman art on April 20, 2007 blocked up when it served as akitchen, completes the installment of its ancient col- have now been opened up to Central Park. lection,the first part of which, the Belfer In addition to old favorites, there are now Court, displaying pre-Greek and Oriental- many objects that were never before exhib- izing art, was opened in 1996. Abeautifully ited, as well as pieces beautifullydisplayed illustrated, 13-page cover article in Archeo in informative new contexts.Inthe sculp- (March 7, 2007) presents an exclusive pre- ture court here are some spectacular,unex- view: pected Roman portraits: one of a “The heart of the new galleries is the long-haired man in marble and two bronze spectacular Leon Levy and Shelby White heads, perhaps amother and son. Court, amajestic courtyard and peristyle, dedicated to Hellenistic and Roman art; it Continuedonpage 8 occupies an area designed and built by the architectural firm McKim, Mead, and White Etruschi:Lacollezione Bonci Casuccini Chiusi Siena Palermo by Debora Barbagli and Mario Iozzo Translated by Jane Whitehead. -

Spqr: a History of Ancient Rome Pdf, Epub, Ebook

SPQR: A HISTORY OF ANCIENT ROME PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mary Beard | 608 pages | 07 Apr 2016 | Profile Books Ltd | 9781846683817 | English | London, United Kingdom SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome PDF Book Documentation, documentation, documentation. The same fundamental mechanisms, structures and dynamics run on until AD then there is a shift towards late antiquity and a Christian Empire, implicitly something so deeply different that it would require another book. There is nothing on the crucifixion. It was the empire itself, Beard persuasively argues, that ultimately produced the rule of the emperors. Community Reviews. Birthplace of so many impressive inventions we take for granted nowadays. I knew vaguely of names and the fact the Roman Empire existed. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Just a moment while we sign you in to your Goodreads account. One thing became clear quite quickly: thanks to the combined efforts of Monty Python and Eddie Izzard, I am entirely unable to take the ancient Romans in any way seriously. But expansion put great power in the hands of individual commanders. Or the sixteenth? I used to read a ton of it but, for reasons I can't recall or explain, I stopped quite a few years ago, focusing entirely on fiction. I loved reading this. Archived from the original on 13 August I just remember the stories and find everything absolutely fascinating. In short this book was both a fascinating insight in to Roman history but also exposed how certain forms of governance have not changed in all these years. -

Rome Compiled Background Guide Final Online

Roman Republic (1849) MUNUC 33 ONLINE1 Roman Republic (1849) | MUNUC 33 Online TABLE OF CONTENTS ______________________________________________________ CHAIR LETTER……………………………….………………………….……..…3 CRISIS DIRECTOR LETTER……………………………………………………….5 ANCIENT ROME………………………………………………………………….7 MODERN CONTEXT OF ROME AND THE PAPAL STATES…………………..22 CURRENT ISSUES………………………………………………………………. 36 MAP…………………………………………………………………………….. 39 CHARACTER BIOGRAPHIES…………………………………………………. 40 BIBLIOGRAPHY………………………………………………………………...59 2 Roman Republic (1849) | MUNUC 33 Online CHAIR LETTER ____________________________________________________ Dear Delegates, Welcome to the Roman Republic of 1849! I will be your chair for the weekend of MUNUC, during which time I’ll represent Giuseppe Mazzini. I’m incredibly excited to welcome you to a little-known (and less understood) time in history! The Roman Republic of 1849 represents how people tried to bring ideals of individuality, freedom, and equality to reality. Although the real-world Republic fell to a French invasion, I hope that you can gather your creativity, knowledge, and collaboration to change history and build a Republic that will last. I’m a current senior at the University of Chicago, studying Biology with a specialization in Endocrinology on the pre-medical track. I staff MUNUC, run our collegiate conference ChoMUN as Director-General, and compete on our travel team. Outside of MUN, I do research in a genetic neurobiology lab with fruit flies, volunteer at the UChicago Hospital, and TA for courses such as Organic Chemistry, Genetics, and Core Biology. I also like to write poetry, paint, and perform Shakespeare! If at any point you want to share something or ask a question, on anything from your favorite novel to college life, just reach out to me at [email protected].