Controversies in the Management of Advanced Prostate Cancer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prnu-BICALUTAMIDE

PRODUCT MONOGRAPH PrNU-BICALUTAMIDE Bicalutamide Tablets, 50 mg Non-Steroidal Antiandrogen NU-PHARM INC. DATE OF PREPARATION: 50 Mural Street, Units 1 & 2 October 16, 2009 Richmond Hill, Ontario L4B 1E4 Control#: 133521 Page 1 of 27 Table of Contents PART I: HEALTH PROFESSIONAL INFORMATION....................................................... 3 SUMMARY PRODUCT INFORMATION ............................................................................. 3 INDICATIONS AND CLINICAL USE ................................................................................... 3 CONTRAINDICATIONS ........................................................................................................ 3 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS....................................................................................... 4 ADVERSE REACTIONS......................................................................................................... 5 DRUG INTERACTIONS ......................................................................................................... 9 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION ................................................................................... 10 OVERDOSAGE...................................................................................................................... 10 ACTION AND CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY.................................................................. 10 STORAGE AND STABILITY............................................................................................... 11 DOSAGE FORMS, COMPOSITION AND PACKAGING -

Prostate Cancer Causes, Risk Factors, and Prevention Risk Factors

cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 Prostate Cancer Causes, Risk Factors, and Prevention Risk Factors A risk factor is anything that increases your chances of getting a disease such as cancer. Learn more about the risk factors for prostate cancer. ● Prostate Cancer Risk Factors ● What Causes Prostate Cancer? Prevention There is no sure way to prevent prostate cancer. But there are things you can do that might lower your risk. Learn more. ● Can Prostate Cancer Be Prevented? Prostate Cancer Risk Factors A risk factor is anything that raises your risk of getting a disease such as cancer. Different cancers have different risk factors. Some risk factors, like smoking, can be changed. Others, like a person’s age or family history, can’t be changed. But having a risk factor, or even several, does not mean that you will get the disease. 1 ____________________________________________________________________________________American Cancer Society cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 Many people with one or more risk factors never get cancer, while others who get cancer may have had few or no known risk factors. Researchers have found several factors that might affect a man’s risk of getting prostate cancer. Age Prostate cancer is rare in men younger than 40, but the chance of having prostate cancer rises rapidly after age 50. About 6 in 10 cases of prostate cancer are found in men older than 65. Race/ethnicity Prostate cancer develops more often in African-American men and in Caribbean men of African ancestry than in men of other races. And when it does develop in these men, they tend to be younger. -

Hormones and Breeding

IN-DEPTH: REPRODUCTIVE ENDOCRINOLOGY Hormones and Breeding Carlos R.F. Pinto, MedVet, PhD, Diplomate ACT Author’s address: Theriogenology and Reproductive Medicine, Department of Veterinary Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210; e-mail: [email protected]. © 2013 AAEP. 1. Introduction affected by PGF treatment to induce estrus. In The administration of hormones to mares during other words, once luteolysis takes place, whether breeding management is an essential tool for equine induced by PGF treatment or occurring naturally, practitioners. Proper and timely administration of the events that follow (estrus behavior, ovulation specific hormones to broodmares may be targeted to and fertility) are essentially similar or minimally prevent reproductive disorders, to serve as an aid to affected (eg, decreased signs of behavioral estrus). treating reproductive disorders or hormonal imbal- Duration of diestrus and interovulatory intervals ances, and to optimize reproductive efficiency, for are shortened after PGF administration.1 The example, through induction of estrus or ovulation. equine corpus luteum (CL) is responsive to PGF These hormones, when administered exogenously, luteolytic effects any day after ovulation; however, act to control the duration and onset of the different only CL Ͼ5 days are responsive to one bolus injec- stages of the estrous cycle, specifically by affecting tion of PGF.2,3 Luteolysis or antiluteogenesis can duration of luteal function, hastening ovulation es- be reliably achieved in CL Ͻ5 days only if multiple pecially for timed artificial insemination and stimu- PGF treatments are administered. For that rea- lating myometrial activity in mares susceptible to or son, it became a widespread practice to administer showing delayed uterine clearance. -

CASODEX (Bicalutamide)

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION • Gynecomastia and breast pain have been reported during treatment with These highlights do not include all the information needed to use CASODEX 150 mg when used as a single agent. (5.3) CASODEX® safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for • CASODEX is used in combination with an LHRH agonist. LHRH CASODEX. agonists have been shown to cause a reduction in glucose tolerance in CASODEX® (bicalutamide) tablet, for oral use males. Consideration should be given to monitoring blood glucose in Initial U.S. Approval: 1995 patients receiving CASODEX in combination with LHRH agonists. (5.4) -------------------------- RECENT MAJOR CHANGES -------------------------- • Monitoring Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) is recommended. Evaluate Warnings and Precautions (5.2) 10/2017 for clinical progression if PSA increases. (5.5) --------------------------- INDICATIONS AND USAGE -------------------------- ------------------------------ ADVERSE REACTIONS ----------------------------- • CASODEX 50 mg is an androgen receptor inhibitor indicated for use in Adverse reactions that occurred in more than 10% of patients receiving combination therapy with a luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone CASODEX plus an LHRH-A were: hot flashes, pain (including general, back, (LHRH) analog for the treatment of Stage D2 metastatic carcinoma of pelvic and abdominal), asthenia, constipation, infection, nausea, peripheral the prostate. (1) edema, dyspnea, diarrhea, hematuria, nocturia, and anemia. (6.1) • CASODEX 150 mg daily is not approved for use alone or with other treatments. (1) To report SUSPECTED ADVERSE REACTIONS, contact AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP at 1-800-236-9933 or FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088 or ---------------------- DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION ---------------------- www.fda.gov/medwatch The recommended dose for CASODEX therapy in combination with an LHRH analog is one 50 mg tablet once daily (morning or evening). -

Campro Catalog Stable Isotope

Introduction & Welcome Dear Valued Customer, We are pleased to present to you our Stable Isotopes Catalog which contains more than three thousand (3000) high quality labeled compounds. You will find new additions that are beneficial for your research. Campro Scientific is proud to work together with Isotec, Inc. for the distribution and marketing of their stable isotopes. We have been working with Isotec for more than twenty years and know that their products meet the highest standard. Campro Scientific was founded in 1981 and we provide services to some of the most prestigious universities, research institutes and laboratories throughout Europe. We are a research-oriented company specialized in supporting the requirements of the scientific community. We are the exclusive distributor of some of the world’s leading producers of research chemicals, radioisotopes, stable isotopes and environmental standards. We understand the requirements of our customers, and work every day to fulfill them. In working with us you are guaranteed to receive: - Excellent customer service - High quality products - Dependable service - Efficient distribution The highly educated staff at Campro’s headquarters and sales office is ready to assist you with your questions and product requirements. Feel free to call us at any time. Sincerely, Dr. Ahmad Rajabi General Manager 180/280 = unlabeled 185/285 = 15N labeled 181/281 = double labeled (13C+15N, 13C+D, 15N+18O etc.) 186/286 = 12C labeled 182/282 = d labeled 187/287 = 17O labeled 183/283 = 13C labeleld 188/288 = 18O labeled 184/284 = 16O labeled, 14N labeled 189/289 = Noble Gases Table of Contents Ordering Information.................................................................................................. page 4 - 5 Packaging Information .............................................................................................. -

Hormonal Treatment Strategies Tailored to Non-Binary Transgender Individuals

Journal of Clinical Medicine Review Hormonal Treatment Strategies Tailored to Non-Binary Transgender Individuals Carlotta Cocchetti 1, Jiska Ristori 1, Alessia Romani 1, Mario Maggi 2 and Alessandra Daphne Fisher 1,* 1 Andrology, Women’s Endocrinology and Gender Incongruence Unit, Florence University Hospital, 50139 Florence, Italy; [email protected] (C.C); jiska.ristori@unifi.it (J.R.); [email protected] (A.R.) 2 Department of Experimental, Clinical and Biomedical Sciences, Careggi University Hospital, 50139 Florence, Italy; [email protected]fi.it * Correspondence: fi[email protected] Received: 16 April 2020; Accepted: 18 May 2020; Published: 26 May 2020 Abstract: Introduction: To date no standardized hormonal treatment protocols for non-binary transgender individuals have been described in the literature and there is a lack of data regarding their efficacy and safety. Objectives: To suggest possible treatment strategies for non-binary transgender individuals with non-standardized requests and to emphasize the importance of a personalized clinical approach. Methods: A narrative review of pertinent literature on gender-affirming hormonal treatment in transgender persons was performed using PubMed. Results: New hormonal treatment regimens outside those reported in current guidelines should be considered for non-binary transgender individuals, in order to improve psychological well-being and quality of life. In the present review we suggested the use of hormonal and non-hormonal compounds, which—based on their mechanism of action—could be used in these cases depending on clients’ requests. Conclusion: Requests for an individualized hormonal treatment in non-binary transgender individuals represent a future challenge for professionals managing transgender health care. For each case, clinicians should balance the benefits and risks of a personalized non-standardized treatment, actively involving the person in decisions regarding hormonal treatment. -

How to Select Pharmacologic Treatments to Manage Recidivism Risk in Sex Off Enders

How to select pharmacologic treatments to manage recidivism risk in sex off enders Consider patient factors when choosing off -label hormonal and nonhormonal agents ® Dowden Healthex offenders Media traditionally are managed by the criminal justice system, but psychiatrists are fre- Squently called on to assess and treat these indi- CopyrightFor personalviduals. use Part only of the reason is the overlap of paraphilias (disorders of sexual preference) and sexual offending. Many sexual offenders do not meet DSM criteria for paraphilias,1 however, and individuals with paraphil- ias do not necessarily commit offenses or come into contact with the legal system. As clinicians, we may need to assess and treat a wide range of sexual issues, from persons with paraphilias who are self-referred and have no legal involvement, to recurrent sexual offenders who are at a high risk of repeat offending. Successfully managing sex offenders includes psychological and pharmacologic interven- 2009 © CORBIS / TIM PANNELL 2009 © CORBIS / tions and possibly incarceration and post-incarceration Bradley D. Booth, MD surveillance. This article focuses on pharmacologic in- Assistant professor terventions for male sexual offenders. Department of psychiatry Director of education Integrated Forensics Program University of Ottawa Reducing sexual drive Ottawa, ON, Canada Sex offending likely is the result of a complex inter- play of environment and psychological and biologic factors. The biology of sexual function provides nu- merous targets for pharmacologic intervention, in- cluding:2 • endocrine factors, such as testosterone • neurotransmitters, such as serotonin. The use of pharmacologic treatments for sex of- fenders is off-label, and evidence is limited. In general, Current Psychiatry 60 October 2009 pharmacologic treatments are geared toward reducing For mass reproduction, content licensing and permissions contact Dowden Health Media. -

Hertfordshire Medicines Management Committee (Hmmc) Nafarelin for Endometriosis Amber Initiation – Recommended for Restricted Use

HERTFORDSHIRE MEDICINES MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE (HMMC) NAFARELIN FOR ENDOMETRIOSIS AMBER INITIATION – RECOMMENDED FOR RESTRICTED USE Name: What it is Indication Date Decision NICE / SMC generic decision status Guidance (trade) last revised Nafarelin A potent agonistic The hormonal December Final NICE NG73 2mg/ml analogue of management of 2020 Nasal Spray gonadotrophin endometriosis, (Synarel®) releasing hormone including pain relief and (GnRH) reduction of endometriotic lesions HMMC recommendation: Amber initiation across Hertfordshire (i.e. suitable for primary care prescribing after specialist initiation) as an option in endometriosis Background Information: Gonadorelin analogues (or gonadotrophin-releasing hormone agonists [GnRHas]) include buserelin, goserelin, leuprorelin, nafarelin and triptorelin. The current HMMC decision recommends triptorelin as Decapeptyl SR® injection as the gonadorelin analogue of choice within licensed indications (which include endometriosis) link to decision. A request was made by ENHT to use nafarelin nasal spray as an alternative to triptorelin intramuscular injection during the COVID-19 pandemic. The hospital would provide initial 1 month supply, then GPs would continue for further 5 months as an alternative to the patient attending for further clinic appointments for administration of triptorelin. Previously at ENHT, triptorelin was the only gonadorelin analogue on formulary for gynaecological indications. At WHHT buserelin nasal spray 150mcg/dose is RED (hospital only) for infertility & endometriosis indications. Nafarelin nasal spray 2mg/ml is licensed for: . The hormonal management of endometriosis, including pain relief and reduction of endometriotic lesions. Use in controlled ovarian stimulation programmes prior to in-vitro fertilisation, under the supervision of an infertility specialist. Use of nafarelin in endometriosis aims to induce chronic pituitary desensitisation, which gives a menopause-like state maintained over many months. -

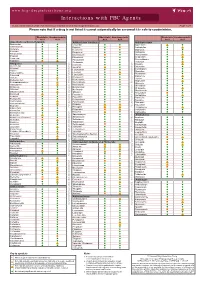

Interactions with PBC Agents

www.hep-druginteractions.org Interactions with PBC Agents Charts created March 2020. Full information available at www.hep-druginteractions.org Page 1 of 4 Please note that if a drug is not listed it cannot automatically be assumed it is safe to coadminister. Obeticholic Ursodeoxycholic Obeticholic Ursodeoxycholic Obeticholic Ursodeoxycholic Acid Acid Acid Acid Acid Acid Anaesthetics & Muscle Relaxants Antibacterials (continued) Antidepressants Bupivacaine Cloxacillin Agomelatine Cisatracurium Dapsone Amitriptyline Isoflurane Delamanid Bupropion Ketamine Ertapenem Citalopram Nitrous oxide Erythromycin Clomipramine Propofol Ethambutol Desipramine Thiopental Flucloxacillin Desvenlafaxine Tizanidine Gentamicin Dosulepin Analgesics Imipenem Doxepin Aceclofenac Isoniazid Duloxetine Alfentanil Escitalopram Aspirin Levofloxacin Linezolid Fluoxetine Buprenorphine Fluvoxamine Lymecycline distribution. Celecoxib Imipramine Meropenem Codeine Lithium Methenamine Dexketoprofen Maprotiline Metronidazole Dextropropoxyphene Mianserin Moxifloxacin Diamorphine Milnacipran Diclofenac Nitrofurantoin only. Not for distribution. for only. Not Mirtazapine Diflunisal Norfloxacin Moclobemide Dihydrocodeine Ofloxacin Nefazodone Etoricoxib Penicillin V Nortriptyline Fentanyl Piperacillin Paroxetine Flurbiprofen Pivmecillinam Sertraline Hydrocodone use ersonal Pyrazinamide Tianeptine Hydromorphone Rifabutin Trazodone Ibuprofen Rifampicin -

Determination of 17 Hormone Residues in Milk by Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography and Triple Quadrupole Mass Spectrom

No. LCMSMS-065E Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry Determination of 17 Hormone Residues in Milk by Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography and Triple Quadrupole No. LCMSMS-65E Mass Spectrometry This application news presents a method for the determination of 17 hormone residues in milk using Shimadzu Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatograph (UHPLC) LC-30A and Triple Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer LCMS- 8040. After sample pretreatment, the compounds in the milk matrix were separated using UPLC LC-30A and analyzed via Triple Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer LCMS-8040. All 17 hormones displayed good linearity within their respective concentration range, with correlation coefficient in the range of 0.9974 and 0.9999. The RSD% of retention time and peak area of 17 hormones at the low-, mid- and high- concentrations were in the range of 0.0102-0.161% and 0.563-6.55% respectively, indicating good instrument precision. Method validation was conducted and the matrix spike recovery of milk ranged between 61.00-110.9%. The limit of quantitation was 0.14-0.975 g/kg, and it meets the requirement for detection of hormones in milk. Keywords: Hormones; Milk; Solid phase extraction; Ultra performance liquid chromatograph; Triple quadrupole mass spectrometry ■ Introduction Since 2008’s melamine-tainted milk scandal, the With reference to China’s national standard GB/T adulteration of milk powder has become a major 21981-2008 "Hormone Multi-Residue Detection food safety concern. In recent years, another case of Method for Animal-derived Food - LC-MS Method", dairy product safety is suspected to cause "infant a method utilizing solid phase extraction, ultra- sexual precocity" (also known as precocious puberty) performance liquid chromatography and triple and has become another major issue challenging the quadrupole mass spectrometry was developed for dairy industry in China. -

CANVAS Trial)

Effectiveness research with Real World Data to support FDA’s regulatory decision making 1. RCT Details This section provides a high-level overview of the RCT that the described real-world evidence study is trying to replicate as closely as possible given the remaining limitations inherent in the healthcare databases. 1.1 Title Canagliflozin and Cardiovascular and Renal Events in Type 2 Diabetes (CANVAS trial) 1.2 Intended aim(s) To compare canagliflozin to placebo on cardiovascular (CV) events including CV death, heart attack, and stroke in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), whose diabetes is not well controlled at the beginning of the study and who have a history of CV events or have a high risk for CV events. 1.3 Primary endpoint for replication and RCT finding Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events, Including CV Death, Nonfatal Myocardial Infarction (MI), and Nonfatal Stroke 1.4 Required power for primary endpoint and noninferiority margin (if applicable) With 688 cardiovascular safety events recorded across the trials, there would be at least 90% power, at an alpha level of 0.05, to exclude an upper margin of the 95% confidence interval for the hazard ratio of 1.3. 1.5 Primary trial estimate targeted for replication HR = 0.86 (95% CI 0.75–0.97) comparing canagliflozin to placebo (Neal et al., 2017) 2. Person responsible for implementation of replication in Aetion Ajinkya Pawar, Ph.D. implemented the study design in the Aetion Evidence Platform. S/he is not responsible for the validity of the design and analytic choices. All implementation steps are recorded and the implementation history is archived in the platform. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9.498,431 B2 Xu Et Al

USOO9498431B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9.498,431 B2 Xu et al. (45) Date of Patent: Nov. 22, 2016 (54) CONTROLLED RELEASING COMPOSITION 7,053,134 B2 * 5/2006 Baldwin et al. .............. 522,154 2004/0058056 A1 3/2004 Osaki et al. ................... 427.2.1 (76) Inventors: Jianjian Xu, Hefei (CN); Shiliang 2005/0037047 A1 2/2005 Song Wang, Hefei (CN); Manzhi Ding 2007/0055364 A1* 3/2007 Hossainy .................. A61F 2/82 s: s s 623, 1.38 Hefei (CN) 2008/0274194 A1* 11/2008 Miller .................... A61K 9.146 424/489 (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this patent is extended or adjusted under 35 FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. CN 1208.610 A 2, 1999 (21) Appl. No.: 13/133,656 EP O251680 A2 1, 1988 JP S63-22516. A 1, 1988 JP H1O-310518 A 11, 1998 (22) PCT Filed: Dec. 10, 2009 WO 96,10395 A1 4f1996 WO WO 2005.000277 A1 * 1, 2005 (86). PCT No.: PCT/CN2009/075468 WO 2007 115045 A2 10, 2007 WO 2008/OO2657 A2 1, 2008 S 371 (c)(1), WO 2008OO2657 A2 1, 2008 (2), (4) Date: Jun. 9, 2011 WO 2008041246 A2 4/2008 (87) PCT Pub. No.: WO2010/066203 OTHER PUBLICATIONS PCT Pub. Date: Jun. 17, 2010 Crowley and Zhang, Pharmaceutical Application of Hot Melt Extru (65) Prior Publication Data sion: Part I, Drug Development and Industrial Pharmacy, 2007. 33:909-926.* US 2011/024.4043 A1 Oct. 6, 2011 The Use of Poly (L-Lactide) and RGD Modified Microspheres as Cell Carriers in a Flow Intermittency Bioreactor for Tissue Engi (30) Foreign Application Priority Data neering Cartilage.