Wide Angle a Journal of Literature and Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uyghur Dispossession, Culture Work and Terror Capitalism in a Chinese Global City Darren T. Byler a Dissertati

Spirit Breaking: Uyghur Dispossession, Culture Work and Terror Capitalism in a Chinese Global City Darren T. Byler A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2018 Reading Committee: Sasha Su-Ling Welland, Chair Ann Anagnost Stevan Harrell Danny Hoffman Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Anthropology ©Copyright 2018 Darren T. Byler University of Washington Abstract Spirit Breaking: Uyghur Dispossession, Culture Work and Terror Capitalism in a Chinese Global City Darren T. Byler Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Sasha Su-Ling Welland, Department of Gender, Women, and Sexuality Studies This study argues that Uyghurs, a Turkic-Muslim group in contemporary Northwest China, and the city of Ürümchi have become the object of what the study names “terror capitalism.” This argument is supported by evidence of both the way state-directed economic investment and security infrastructures (pass-book systems, webs of technological surveillance, urban cleansing processes and mass internment camps) have shaped self-representation among Uyghur migrants and Han settlers in the city. It analyzes these human engineering and urban planning projects and the way their effects are contested in new media, film, television, photography and literature. It finds that this form of capitalist production utilizes the discourse of terror to justify state investment in a wide array of policing and social engineering systems that employs millions of state security workers. The project also presents a theoretical model for understanding how Uyghurs use cultural production to both build and refuse the development of this new economic formation and accompanying forms of gendered, ethno-racial violence. -

The Funerals of the Habsburg Emperors in the Eighteenth Century

The Funerals of the Habsburg Emperors In the Eighteenth Century MARK HENGERER 1. Introduction The dassic interpretation of the eighteenth century as aperiod of transition-from sacred kingship to secular state, from a divine-right monarchy to enlightened absolutism, from religion to reason-neglects, so the editor of this volume suggests, aspects of the continuing impact of religion on European royal culture during this period, and ignores the fact that secularization does not necessarily mean desacralization. If we take this point of view, the complex relationship between monarchy and religion, such as appears in funerals, needs to be revisited. We still lack a comparative and detailed study of Habsburg funerals throughout the entire eighteenth century. Although the funerals of the emperors in general have been the subject of a great deal of research, most historians have concentrated either on funerals of individual ruIers before 1700, or on shorter periods within the eighteenth century.l Consequently, the general view I owe debts of gratitude to MeJana Heinss Marte! and Derek Beales for their romments on an earlier version ofthis essay, and to ThomasJust fi'om the Haus-, Hof und Staatsarchiv, Vienna, for unbureaucratic access to the relevant source material. I Most attention has heen paid to Emperor Maximilian 1. Cf., among olhers, Peter Schmid, 'Sterben-Tod-Leichenbegängnis Kaiser Maximilians 1.', in Lothar Kolmer (ed.), Der Tod des A1iichtigen: Kult und Kultur des Sterbe1l5 spätmittelalterlicher Herrscher (Paderborn, 1997), 185-215; Elisaheth Scheicher, 'Kaiser Maximilian plant sein Denkmal', Jahrbuch des kunsthislmischen Museums Wien, I (1999), 81-117; Gabriele Voss, 'Der Tod des Herrschers: Sterbe- und Beerdigungsbrauchtum beim Übertritt vom Mittelalter in die frühe Neuzeit am Beispiel der Kaiser Friedrich IH., Maximilian L und Kar! V: (unpuhlished Diploma thesis, University ofVienna, 1989). -

Rome Hotel Eden

ROME HOTEL EDEN Two day itinerary: Teenagers With strong historical and cultural appeal, it isn’t difficult to find activities to entertain and educate the whole family in Rome. While travelling with teenagers can have its challenges, the key to a fantastic trip lies in a little imagination and a lot of creative planning. Visit these popular places for teenagers with this two-day travel guide to Rome. Day One Start the day with a 15-minute drive to Castel Sant’Angelo, crossing over the River Tiber. CASTEL SANT’ANGELO T: 006 32810 | Lungotevere Castello 50, 00193 Rome An unmissable attraction for history buffs, Castel Sant’Angelo is more than just a castle. The ancient Roman fortress is home to Hadrian’s tomb, built by the 2nd century emperor himself. Starting at the tomb, young adventurers can explore the castle and discover the National Museum of Castel Sant’Angelo with its collections of antique weapons, pottery and art. Next, take a leisurely 10-minute walk to St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City. ST PETER’S BASILICA T: 006 6988 3229 | Piazza San Pietro, Vatican City, 00120 Instantly recognisable by its enormous domed roof, St Peter’s Basilica is among the most famous sights in Rome. Treat teenagers to an alternative view by climbing to the top of the dome. From the roof level of the basilica, it’s over 500 steps to the top of the dome, but it’s worth the effort for incredible panoramic views of the Eternal City. To reach Pizzarium, take either a 10-minute drive or a 20-minute walk. -

Susanne Goldfarb: Oral History Transcript

Susanne Goldfarb: Oral History Transcript www.wisconsinhistory.org/HolocaustSurvivors/Goldfarb.asp Name: Susanne Hafner Goldfarb (1933–1987) Birth Place: Vienna, Austria Arrived in Wisconsin: 1969, Madison Project Name: Oral Histories: Wisconsin Survivors Susanne Goldfarb of the Holocaust Biography: Susanne Hafner Goldfarb was born in Vienna, Austria, on February 17, 1933. She was the only child of a middle-class Jewish family. Nazi Germany annexed Austria in March 1938. Rising anti-Semitism and the threat of war prompted her family to flee their homeland in early 1939. Six-year-old Susanne and her family left Europe on a luxury liner bound for Shanghai, China. They found refuge with more than 20,000 other European Jewish exiles in the Japanese-occupied sector of that city. The refugees were able to create a multifaceted Jewish community in Shanghai. It included commercial, religious, cultural, and educational institutions. Susanne attended synagogue, studied in Jewish schools, and belonged to a Zionist social club. The Hafners eked out a living by delivering bread in their neighborhood, the Hongkew district. In May 1943, Japanese authorities introduced anti-Semitic measures. The Hongkew district turned into a Jewish ghetto and all Shanghai Jews were restricted to this area. As World War II unfolded, Shanghai came under increased assault from U.S. warplanes. Susanne's family worked as air raid wardens and suffered the terror of heavy bombing attacks. In August 1945, the U.S. liberated the Hongkew Ghetto. Soon after, China descended into civil war. In 1949 the Chinese Communists came to power. The Hafners, fearing persecution under the communist regime, immigrated to Israel in January 1949. -

April Alford, Mary Shielding the Amish Witness

The Elyria Public Library System Fiction List Spring 2021 provided by your librarians April Alford, Mary Shielding the Amish Witness – When Faith Cooper seeks refuge in Amish Country she puts everyone she loves in danger, and it is up to her childhood friend Eli to protect her against a ruthless killer who has nothing left to lose. Ames, Jonathan A Man Named Doll -mystery - Happy Doll is a PI living with his dog, George, and working at a local Thai spa.He has two rules: bark loudly and act first. When faced with a violent patron he finds himself out of his depth. Anderson, Natalie Stranded for One Scandalous Week – romance – (Book One in the Rebels, Brothers, Billionaires Series) The innocent, the playboy, and their seven night passion – is it enough to ignite a lifetime of love? Archer, Jeffrey Turn a Blind Eye-mystery- (Book 3 in the William Warwick Chronicle Series) New Detective Inspector William Warwick is tasked to go undercover and expose corruption at the heart of the Metropolitan Police Force. Baldacci, David A Gambling Man -mystery- (Book 2 in the Aloysius Archer Series) When two seemingly unconnected people are murdered at a burlesque club, Archer must dig deep to reveal the connection between the victims. Bannalec, Jean-Luc The Granite Coast Murders -mystery- (Book 6 in the Brittany Mystery Series) Commissaire Dupin returns to investigate a murder at a gorgeous Brittany beach resort. Beck, Kristin Courage My Love -romance- When the Nazi occupation of Rome begins, two courageous young women are plunged deep into the Italian Resistance to fight for their freedom in this captivating debut novel. -

TRUTH.FICTION.LIES Confessions of an Italian-Irish-Catholic- American Immigrant to Canada by PATRICK X WALSH NONFICTION

A DECADE OF JOURNEYS TAKEN & STORIES TOLD 257 million words, 1.7 million books sold, & over 5,000 unique titles (and counting). FriesenPress turns 10 years old on July 13, 2019! And we’re marking the occasion by looking back at the authors and stories that made it possible. Join us as we celebrate a decade of journeys taken and stories told: visit friesenpress.com/ friesenpress10 for infographics, video, a suite of original stories about the past, present and future of self-publishing, and more! F FICTION BOOKS FICTION 2019 BESTSELLERS ENCOMPASSING THE BREAD MAKER OR SO IT SEEMED THE JOY OF DISCOVERY CELTIC KNOT DARKNESS BY MOIRA LEIGH BY MOIRA LEIGH BY J.R. GILLETTE BY ANN SHORTELL BY TERAH MARIE MACLEOD MACLEOD HARDCOVER HARDCOVER HARDCOVER HARDCOVER HARDCOVER $35.99 USD | Reg Disc $26.99 USD | Reg Disc $31.99 USD | Reg Disc $41.99 USD | Reg Disc $37.99 USD | Reg Disc 978-1-4602-0113-8 978-1-5255-2090-7 978-1-5255-3119-4 978-1-4602-7217-6 978-1-5255-1734-1 PAPERBACK PAPERBACK PAPERBACK PAPERBACK PAPERBACK $23.99 USD | Reg Disc $19.6 USD | Reg Disc $15.99 USD | Reg Disc $31.99 USD | Reg Disc $22.99 USD | Reg Disc 978-1-4602-0114-5 978-1-5255-2091-4 978-1-5255-3120-0 978-1-4602-7218-3 978-1-5255-1735-8 EBOOK EBOOK EBOOK EBOOK EBOOK $1.99 USD $3.99 USD $3.99 USD $6.99 USD $6.99 USD 978-1-4602-0115-2 978-1-4602-9207-5 978-1-5255-3121-7 978-1-4602-7219-0 978-1-5255-1736-5 M.C. -

The Dysphoric Style in Contemporary American Independent Cinema David C

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 The Dysphoric Style in Contemporary American Independent Cinema David C. Simmons Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE DYSPHORIC STYLE IN CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN INDEPENDENT CINEMA By DAVID C. SIMMONS A Dissertation submitted to the Program in the Humanities in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2005 Copyright (c) 2005 David C. Simmons All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of David C. Simmons defended on April 11, 2005. ____________________________________ Karen L. Laughlin Professor Co-Directing Dissertation ____________________________________ Mark Garrett Cooper Professor Co-Directing Dissertation ____________________________________ Valliere Richard Auzenne Outside Committee Member ____________________________________ William J. Cloonan Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________ David F. Johnson Director, Program in the Humanities The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the assistance of Sandefur Schmidt and my mother, Rita Simmons. I gratefully acknowledge both of them for the immense kindness and help they’ve provided me. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ................................................................... v INTRODUCTION: THE DYSPHORIC STYLE IN CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN INDEPENDENT CINEMA ................. 1 1. TRYING TO HOLD ONTO A PIECE OF PI: THE DYSPHORIC STYLE’S STRUCTURING OF CAUSAL RELATIONS ......... 7 2. FACT OR PULP FICTION: THE DYSPHORIC STYLE AND TEMPORAL RELATIONS .................... 26 3. “THE COOKIE STAND IS NOT PART OF THE FOOD COURT”: THE DYSPHORIC STYLE AND SPATIAL RELATIONS ...................... -

Cinéma Du Nord

A North Wind THE NEW REALISM OF THE FRENCH- WALLOON CINÉMA DU NORD A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY NIELS NIESSEN IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ADVISER: CESARE CASARINO NOVEMBER, 2013 © Niels Niessen, 2013 i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Ideas sometimes come in the middle of the night yet they are never fully one’s own. They are for a very large part the fruits of the places and organizations one works or is supported by, the communities one lives in and traverses, and the people one loves and is loved by. First of all, I would like to acknowledge the support I received from the following institutions: the American Council of Learned Societies, the Huygens Scholarship Program of the Dutch government, the Prins Bernard Cultuurfonds (The Netherlands), and, at the University of Minnesota, the Center for German & European Studies (and its donor Hella Mears), the Graduate School (and the Harold Leonard Memorial Fellowship in Film Study), as well as the Department of Cultural Studies and Comparative Literature. As for my home department, I could not have wished for a warmer and more intellectually vibrant community to pursue my graduate studies, and I express my gratitude to all who I have worked with. A special word of thanks to my academic adviser, Cesare Casarino, who has taught me how to read many of the philosophies that, explicitly or implicitly, have shaped my thinking in the following pages, and who has made me see that cinema too is a form of thought. -

The Road Narrative in Contemporary American

THIS IS NOT AN EXIT: THE ROAD NARRATIVE IN CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN LITERATURE AND FILM by JILL LYNN TALBOT, B.S.Ed., M.A. A DISSERTATION IN ENGLISH Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Accepted Dean (C(f the Graduate School May, 1999 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my dissertation director, Dr. Bryce Conrad, for agreeing to work with me on this project and for encouraging me to remain cognizant of its scope and its overall significance, both now and in the future. Thanks also to committee member Dr. Patrick Shaw, who not only introduced me to an American fiction that I could appreciate and devote myself to in both my personal and professional life, but who has guided me from my first analysis of On the Road, which led to this project. Thanks also to committee member Dr. Bill Wenthe, for his friendship and his decision to be a part of this process. I would also like to thank those individuals who have been supportive and enthusiastic about this project, but mostly patient enough to listen to all my ideas, frustrations, and lengthy ruminations on the aesthetics of the road narrative during this past year. Last, I need to thank my true companion, who shares my love not only for roads, but certain road songs, along with all the images promised by the "road away from Here." 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii ABSTRACT v CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. THE REALITY OF THE ROAD: THE NON-FICTION ROAD NARRATIVE 2 6 John Steinbeck's Travels with Charley: In Search of America 27 William Least Heat-Moon's Blue Highways: A Journey into America 35 John A. -

“Meditation” for Fauré's Requiem Palm Sunday April 14

“Meditation” for Fauré’s Requiem Palm Sunday April 14, 2019 Faith Presbyterian Church – Evening Service Pr. Nicoletti When I told someone I know outside of our congregation about our program tonight … they were puzzled … and I suspect a little put off. Their response was something like “Oookay … why would you do that?” Because tonight, our program, is essentially a musical work that is focused on death and dying, and what follows that. Why would a group of people, on a Sunday evening like tonight, gather together to meditate on death and dying? The question brings out how counter-cultural our focus tonight is. But it wasn’t always so counter-cultural. The Christian church for much of its history stressed the importance of living our lives now in light of the fact that we will die. Whether in the liturgy and music of the church, as we will hear tonight, in church architecture, or in the visual art of the church, at its best the Church was persistent in reminding itself of the reality of death. A work or genre of art aimed at doing this would be referred to as a memento mori – Latin for “Remember (that) you will die.” My favorite example of a memento mori that I have heard of is in Rome and is called the Capuchin Crypt. It is a small space made up of several tiny chapels beneath a church. And each room, each chapel, is intricately decorated with the carefully arranged bones of 3700 Franciscan friars who had been part of the Capuchin order before their deaths. -

Katalin Káldi: the NUMEROUS and the INNUMEROUS K a Ta Lin K Á Ld

A R T A S R E S E A R C H • H U N G A R I A N U N I V E R S I T Y O F F I N E A R T S D O C T O R A L S C H O O L • A R T A S R E S E A R C H H L U O N O G H A C R S 2020. 02. 18. 7:46 I A L N A R U O N T I C V O E D R S S I T T R Y A O E F N F I I F N F E O A Y Katalin Káldi: R T T I S S R D E O V C I T N O U R A N L A THE NUMEROUS AND THE INNUMEROUS I S R C A H G O N O U L H H C R A E S E R S A T R A • L O O H C S L A R O T C O D S T R A E N I F F O Y T I S R E V I N U N A I R A G N U H • H C R A E S E R S A T R A Katalin Káldi: THE NUMEROUS AND THE INNUMEROUS - - - - - Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit Neque porro quisquam est, qui dolorem ipsum voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo invento re veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. -

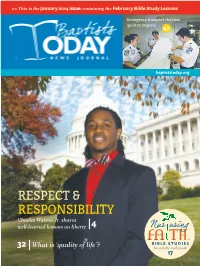

Respect & Responsibility

>> This is the January 2014 issue containing the February Bible Study Lessons Emergency transport chaplain quick to respond 42 baptiststoday.org RESPECT & RESPONSIBILITY Charles Watson Jr. shares well-learned lessons on liberty 4 FA TH™ BIBLE STUDIES 32 What is ‘quality of life’? for adults and youth 17 John D. Pierce Executive Editor BAY PSALM [email protected] BOOK FETCHES Benjamin L. McDade $14.2 MILLION Executive Vice President [email protected] IN RECORD Julie Steele AUCTION Chief Operations Officer [email protected] Jackie B. Riley 35 Managing Editor [email protected] Tony W. Cartledge Contributing Editor [email protected] Bruce T. Gourley Online Editor [email protected] David Cassady Church Resources Editor [email protected] Terri Byrd Contributing Writer PERSPECTIVES Vickie Frayne Art Director The ineffectiveness of in-your-face faith 9 Jannie Lister John Pierce Customer Service Manager [email protected] Remembering a ‘profile in courage’ 30 Kimberly L. Hovis Jack U. Harwell Marketing Associate [email protected] Messy, missional ministry rooted Lex Horton in hospitality 31 Nurturing Faith Resources Manager [email protected] Courtney Allen Walker Knight, Publisher Emeritus Making a difference in a world falling apart 36 Jack U. Harwell, Editor Emeritus Tom Ehrich DIRECTORS EMERITI Thomas H. Boland IN THE NEWS R. Kirby Godsey Mary Etta Sanders Dan Ariail, longtime pastor to Carters, Winnie V. Williams remembered 12 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Baptists focus on ‘waging peace’ 12 14 Donald L. Brewer, Gainesville, Ga. (chairman) Cathy Turner, Clemson, S.C. (vice chair) William Hull, scholar, author, dies at 83 12 Nannette Avery, Signal Mountain, Tenn. The most successful Christian Mary Jane Cardwell, Waycross, Ga.