Peter Williamson 14/02/08 Missing Voices Project Interviewed by Mike Cadman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

The Role of Non-Whites in the South African Defence Force by Cmdt C.J

Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 16, Nr 2, 1986. http://scientiamilitaria.journals.ac.za The Role of Non-Whites in the South African Defence Force by Cmdt C.J. N6thling* assisted by Mrs L. 5teyn* The early period for Blacks, Coloureds and Indians were non- existent. It was, however, inevitable that they As long ago as 1700, when the Cape of Good would be resuscitated when war came in 1939. Hope was still a small settlement ruled by the Dutch East India Company, Coloureds were As war establishment tables from this period subject to the same military duties as Euro- indicate, Non-Whites served as separate units in peans. non-combatant roles such as drivers, stretcher- bearers and batmen. However, in some cases It was, however, a foreign war that caused the the official non-combatant edifice could not be establishment of the first Pandour regiment in maintained especially as South Africa's shortage 1781. They comprised a force under white offi- of manpower became more acute. This under- cers that fought against the British prior to the lined the need for better utilization of Non-Whites occupation of the Cape in 1795. Between the in posts listed on the establishment tables of years 1795-1803 the British employed white units and a number of Non-Whites were Coloured soldiers; they became known as the subsequently attached to combat units and they Cape Corps after the second British occupation rendered active service, inter alia in an anti-air- in 1806. During the first period of British rule craft role. -

The Role and Application of the Union Defence Force in the Suppression of Internal Unrest, 1912 - 1945

THE ROLE AND APPLICATION OF THE UNION DEFENCE FORCE IN THE SUPPRESSION OF INTERNAL UNREST, 1912 - 1945 Andries Marius Fokkens Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Military Science (Military History) at the Military Academy, Saldanha, Faculty of Military Science, Stellenbosch University. Supervisor: Lieutenant Colonel (Prof.) G.E. Visser Co-supervisor: Dr. W.P. Visser Date of Submission: September 2006 ii Declaration I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously submitted it, in its entirety or in part, to any university for a degree. Signature:…………………….. Date:………………………….. iii ABSTRACT The use of military force to suppress internal unrest has been an integral part of South African history. The European colonisation of South Africa from 1652 was facilitated by the use of force. Boer commandos and British military regiments and volunteer units enforced the peace in outlying areas and fought against the indigenous population as did other colonial powers such as France in North Africa and Germany in German South West Africa, to name but a few. The period 1912 to 1945 is no exception, but with the difference that military force was used to suppress uprisings of white citizens as well. White industrial workers experienced this military suppression in 1907, 1913, 1914 and 1922 when they went on strike. Job insecurity and wages were the main causes of the strikes and militant actions from the strikers forced the government to use military force when the police failed to maintain law and order. -

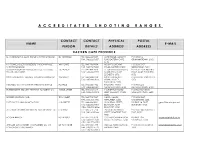

Accreditated Shooting Ranges

A C C R E D I T A T E D S H O O T I N G R A N G E S CONTACT CONTACT PHYSICAL POSTAL NAME E-MAIL PERSON DETAILS ADDRESS ADDRESS EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE D J SURRIDGE T/A ALOE RIDGE SHOOTING RANGE DJ SURRIDGE TEL: 046 622 9687 ALOE RIDGE MANLEY'S P O BOX 12, FAX: 046 622 9687 FLAT, EASTERN CAPE, GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 6140 K V PEINKE (SOLE PROPRIETOR) T/A BONNYVALE WK PEINKE TEL: 043 736 9334 MOUNT COKE KWT P O BOX 5157, SHOOTING RANGE FAX: 043 736 9688 ROAD, EASTERN CAPE GREENFIELDS, 5201 TOMMY BOSCH AND ASSOCIATES CC T/A LOCK, T C BOSCH TEL: 041 484 7818 51 GRAHAMSTAD ROAD, P O BOX 2564, NOORD STOCK AND BARREL FAX: 041 484 7719 NORTH END, PORT EINDE, PORT ELIZABETH, ELIZABETH, 6056 6056 SWALLOW KRANTZ FIREARM TRAINING CENTRE CC WH SCOTT TEL: 045 848 0104 SWALLOW KRANTZ P O BOX 80, TARKASTAD, FAX: 045 848 0103 SPRING VALLEY, 5370 TARKASTAD, 5370 MECHLEC CC T/A OUTSPAN SHOOTING RANGE PL BAILIE TEL: 046 636 1442 BALCRAIG FARM, P O BOX 223, FAX: 046 636 1442 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 BUTTERWORTH SECURITY TRAINING ACADEMY CC WB DE JAGER TEL: 043 642 1614 146 BUFFALO ROAD, P O BOX 867, KING FAX: 043 642 3313 KING WILLIAM'S TOWN, WILLIAM'S TOWN, 5600 5600 BORDER HUNTING CLUB TE SCHMIDT TEL: 043 703 7847 NAVEL VALLEY, P O BOX 3047, FAX: 043 703 7905 NEWLANDS, 5206 CAMBRIDGE, 5206 EAST CAPE PLAINS GAME SAFARIS J G GREEFF TEL: 046 684 0801 20 DURBAN STREET, PO BOX 16, FORT [email protected] FAX: 046 684 0801 BEAUFORT, FORT BEAUFORT, 5720 CELL: 082 925 4526 BEAUFORT, 5720 ALL ARMS FIREARM ASSESSMENT AND TRAINING CC F MARAIS TEL: 082 571 5714 -

Vietnam War Turning Back the Clock 93 Year Old Arctic Convoy Veteran Visits Russian Ship

Military Despatches Vol 33 March 2020 Myths and misconceptions Things we still get wrong about the Vietnam War Turning back the clock 93 year old Arctic Convoy veteran visits Russian ship Battle of Ia Drang First battle between the Americans and NVA For the military enthusiast CONTENTS March 2020 Click on any video below to view How much do you know about movie theme songs? Take our quiz and find out. Hipe’s Wouter de The old South African Page 14 Goede interviews former Defence Force used 28’s gang boss David a mixture of English, South Vietnamese Williams. Afrikaans, slang and techno-speak that few Special Forces outside the military could hope to under- stand. Some of the terms Features 32 were humorous, some Weapons and equipment were clever, while others 6 We look at some of the uniforms were downright crude. Ten myths about Vietnam and equipment used by the US Marine Corps in Vietnam dur- Although it ended almost 45 ing the 1960s years ago, there are still many Part of Hipe’s “On the myths and misconceptions 34 couch” series, this is an about the Vietnam War. We A matter of survival 26 interview with one of look at ten myths and miscon- This month we look at fish and author Herman Charles ceptions. ‘Mad Mike’ dies aged 100 fishing for survival. Bosman’s most famous 20 Michael “Mad Mike” Hoare, characters, Oom Schalk widely considered one of the 30 Turning back the clock Ranks Lourens. Hipe spent time in world’s best known mercenary, A taxi driver was shot When the Russian missile cruis- has died aged 100. -

The Battle of Congella

REMEMBERING DURBAN’S HISTORICAL TAPESTRY – THE BATTLE OF CONGELLA Researched and written by Udo Richard AVERWEG Tuesday 23rd May 2017 marks an important date in Durban’s historical tapestry – it is the dodransbicentennial (175th) anniversary of the commencement of the Battle of Congella in the greater city of Durban. From a military historical perspective, the Congella battle site was actually named after former Zulu barracks (known as an ikhanda), called kwaKhangela. This was established by King Shaka kaSenzangakhona (ca. 1787 – 1828) to keep a watchful eye on the nearby British traders at Port Natal - the full name of the place was kwaKhangela amaNkengane (‘place of watching over vagabonds’). Shortly after the Battle of Blood River (isiZulu: iMpi yaseNcome) on 16th December 1838, Natalia Republiek was established by the migrant Voortrekkers (Afrikaner Boers, mainly of Dutch descent). It stretched from the Tugela River to the north to present day Port St Johns at the UMzimvubu River to the south. The Natalia Republiek was seeking an independent port of entry, free from British control by conquering the Port Natal trading settlement, which had been settled by mostly British traders on the modern-day site of Durban. However, the governor of the Cape Province, Maj Gen Sir George Thomas Napier KCB (1784 - 1855), stated that his intention was to take military possession of Port Natal and prevent the Afrikaner Boers establishing an independent republic upon the coast with a harbour through which access to the interior could be gained. The Battle of Congella began on 23rd May 1842 between British troops from the Cape Colony and the Afrikaner Boer forces of the Natalia Republiek. -

National Liquor Authority Register

National Liquor Register Q1 2021 2022 Registration/Refer Registered Person Trading Name Activities Registered Person's Principal Place Of Business Province Date of Registration Transfer & (or) Date of ence Number Permitted Relocations or Cancellation alterations Ref 10 Aphamo (PTY) LTD Aphamo liquor distributor D 00 Mabopane X ,Pretoria GP 2016-09-05 N/A N/A Ref 12 Michael Material Mabasa Material Investments [Pty] Limited D 729 Matumi Street, Montana Tuine Ext 9, Gauteng GP 2016-07-04 N/A N/A Ref 14 Megaphase Trading 256 Megaphase Trading 256 D Erf 142 Parkmore, Johannesburg, GP 2016-07-04 N/A N/A Ref 22 Emosoul (Pty) Ltd Emosoul D Erf 842, 845 Johnnic Boulevard, Halfway House GP 2016-10-07 N/A N/A Ref 24 Fanas Group Msavu Liquor Distribution D 12, Mthuli, Mthuli, Durban KZN 2018-03-01 N/A 2020-10-04 Ref 29 Golden Pond Trading 476 (Pty) Ltd Golden Pond Trading 476 (Pty) Ltd D Erf 19, Vintonia, Nelspruit MP 2017-01-23 N/A N/A Ref 33 Matisa Trading (Pty) Ltd Matisa Trading (Pty) Ltd D 117 Foresthill, Burgersfort LMP 2016-09-05 N/A N/A Ref 34 Media Active cc Media Active cc D Erf 422, 195 Flamming Rock, Northriding GP 2016-09-05 N/A N/A Ref 52 Ocean Traders International Africa Ocean Traders D Erf 3, 10608, Durban KZN 2016-10-28 N/A N/A Ref 69 Patrick Tshabalala D Bos Joint (PTY) LTD D Erf 7909, 10 Comorant Road, Ivory Park GP 2016-07-04 N/A N/A Ref 75 Thela Management PTY LTD Thela Management PTY LTD D 538, Glen Austin, Midrand, Johannesburg GP 2016-04-06 N/A 2020-09-04 Ref 78 Kp2m Enterprise (Pty) Ltd Kp2m Enterprise D Erf 3, Cordell -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report

VOLUME THREE Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Introduction to Regional Profiles ........ 1 Appendix: National Chronology......................... 12 Chapter 2 REGIONAL PROFILE: Eastern Cape ..................................................... 34 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in the Eastern Cape........................................................... 150 Chapter 3 REGIONAL PROFILE: Natal and KwaZulu ........................................ 155 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in Natal, KwaZulu and the Orange Free State... 324 Chapter 4 REGIONAL PROFILE: Orange Free State.......................................... 329 Chapter 5 REGIONAL PROFILE: Western Cape.................................................... 390 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in the Western Cape ......................................................... 523 Chapter 6 REGIONAL PROFILE: Transvaal .............................................................. 528 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in the Transvaal ...................................................... -

Music and Militarisation During the Period of the South African Border War (1966-1989): Perspectives from Paratus

Music and Militarisation during the period of the South African Border War (1966-1989): Perspectives from Paratus Martha Susanna de Jongh Dissertation presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Professor Stephanus Muller Co-supervisor: Professor Ian van der Waag December 2020 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (unless to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: 29 July 2020 Copyright © 2020 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract In the absence of literature of the kind, this study addresses the role of music in militarising South African society during the time of the South African Border War (1966-1989). The War on the border between Namibia and Angola took place against the backdrop of the Cold War, during which the apartheid South African government believed that it had to protect the last remnants of Western civilization on the African continent against the communist onslaught. Civilians were made aware of this perceived threat through various civilian and military channels, which included the media, education and the private business sector. The involvement of these civilian sectors in the military resulted in the increasing militarisation of South African society through the blurring of boundaries between the civilian and the military. -

The South African War As Humanitarian Crisis

International Review of the Red Cross (2015), 97 (900), 999–1028. The evolution of warfare doi:10.1017/S1816383116000394 The South African War as humanitarian crisis Elizabeth van Heyningen Dr Elizabeth van Heyningen is an Honorary Research Associate in the Department of Historical Studies at the University of Cape Town. Abstract Although the South African War was a colonial war, it aroused great interest abroad as a test of international morality. Both the Boer republics were signatories to the Geneva Convention of 1864, as was Britain, but the resources of these small countries were limited, for their populations were small and, before the discovery of gold in 1884, government revenues were trifling. It was some time before they could put even the most rudimentary organization in place. In Europe, public support from pro-Boers enabled National Red Cross Societies from such countries as the Netherlands, France, Germany, Russia and Belgium to send ambulances and medical aid to the Boers. The British military spurned such aid, but the tide of public opinion and the hospitals that the aid provided laid the foundations for similar voluntary aid in the First World War. Until the fall of Pretoria in June 1900, the war had taken the conventional course of pitched battles and sieges. Although the capitals of both the Boer republics had fallen to the British by June 1900, the Boer leaders decided to continue the conflict. The Boer military system, based on locally recruited, compulsory commando service, was ideally suited to guerrilla warfare, and it was another two years before the Boers finally surrendered. -

South African Army, 3 September 1939

South African Army 3 September 1939 - July 1940 Defence Headquarters: Pretoria, Transvaal Cape Command: HQ The Castle, Capetown, Cape Province A. Permanent Force Cape Detachment, The Special Service Battalion: Capetown No. 1 Anti-Aircraft Artillery Battery: Bamboevlei, Wynberg (South African Permanent Force and University of Cape Town Active Citizen Force) The Coast Artillery Brigade: HQ The Castle, Capetown 2 Sections of Cape Garrison Artillery designated as Engineers and Signals: Capetown 1st Heavy Battery: Capetown (Composite Battery of Cape Garrison Artillery and South African Permanent Garrison Artillery)(Wynard Battery): Table Bay 2nd Heavy Battery: Simonstown (Composite Battery of Cape Garrison Artillery and South African Permanent Garrison Artillery)(Queen's Battery): Simonstown 1st Medium Battery: Capetown (Composite Battery of Cape Garrison Artillery and South African Permanent Garrison Artillery) 2nd Medium Battery: Capetown (Composite Battery of Cape Garrison Artillery and South African Permanent Garrison Artillery) No. 1 Armoured Train: Capetown (An Active Citizen Force unit with Permanent Force nucleus) The Cape Field Artillery (Prince Albert's Own): Capetown (An Active Citizen Force unit with Permanent Force nucleus) B. Active Citizen Force 3rd Infantry Brigade: HQ Capetown The Duke of Edinburgh's Own Rifles: Capetown The Cape Town Highlanders (The Duke of Connaught and Strathearn's Own): Capetown The Kimberley Regiment: Kimberley 3rd Field Company, South African Engineer Corps: Capetown 8th Infantry Brigade: HQ Oudtshoorn Regiment Westelike Provinsie: Stellenbosch Regiment Suid-Westelike Distrikte: Oudtshoorn Die Middellandse Regiment: Graff-Reinet 8th Field Company, South African Engineer Corps: Capetown 1 Eastern Province Command: HQ East London, Cape Province A. Permanent Force 5th Heavy Battery, South African Permanent Garrison Artillery: East London 6th Heavy Battery, South African Permanent Garrison Artillery: Port Elizabeth B. -

Albany Thicket Biome

% S % 19 (2006) Albany Thicket Biome 10 David B. Hoare, Ladislav Mucina, Michael C. Rutherford, Jan H.J. Vlok, Doug I.W. Euston-Brown, Anthony R. Palmer, Leslie W. Powrie, Richard G. Lechmere-Oertel, Şerban M. Procheş, Anthony P. Dold and Robert A. Ward Table of Contents 1 Introduction: Delimitation and Global Perspective 542 2 Major Vegetation Patterns 544 3 Ecology: Climate, Geology, Soils and Natural Processes 544 3.1 Climate 544 3.2 Geology and Soils 545 3.3 Natural Processes 546 4 Origins and Biogeography 547 4.1 Origins of the Albany Thicket Biome 547 4.2 Biogeography 548 5 Land Use History 548 6 Current Status, Threats and Actions 549 7 Further Research 550 8 Descriptions of Vegetation Units 550 9 Credits 565 10 References 565 List of Vegetation Units AT 1 Southern Cape Valley Thicket 550 AT 2 Gamka Thicket 551 AT 3 Groot Thicket 552 AT 4 Gamtoos Thicket 553 AT 5 Sundays Noorsveld 555 AT 6 Sundays Thicket 556 AT 7 Coega Bontveld 557 AT 8 Kowie Thicket 558 AT 9 Albany Coastal Belt 559 AT 10 Great Fish Noorsveld 560 AT 11 Great Fish Thicket 561 AT 12 Buffels Thicket 562 AT 13 Eastern Cape Escarpment Thicket 563 AT 14 Camdebo Escarpment Thicket 563 Figure 10.1 AT 8 Kowie Thicket: Kowie River meandering in the Waters Meeting Nature Reserve near Bathurst (Eastern Cape), surrounded by dense thickets dominated by succulent Euphorbia trees (on steep slopes and subkrantz positions) and by dry-forest habitats housing patches of FOz 6 Southern Coastal Forest lower down close to the river.