Albany Thicket Biome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparison of Extent and Transformation of South Africa's

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by South East Academic Libraries System (SEALS) Research in Action South African Journal of Science 97, May/June 2001 179 remote sensing applications in South Comparison of extent and Africa. This is a hierarchical framework designed to suit South African conditions, transformation of South Africa’s and incorporates known land-cover types that can be identified in a consistent woodland biome from two national and repetitive manner from high- resolution satellite imagery such as Land- databases sat TM and SPOT.The ‘natural’vegetation classes are based on broad, structural M.W. Thompsona*, E.R. Vinka, D.H.K. Fairbanksb,c, A. Ballancea types only, and are not intended to be and C.M. Shackletona,d equivalent to a floristic or ecological vege- tation classification. It is important to understand that a HE RECENT COMPLETION OF THE SOUTH Fairbanks et al.5 combination of both the NLC database’s TAfrican National Land-Cover Database This paper compares the distribution ‘Woodland’ and ‘Thicket, Bushland, and the Vegetation Map of South Africa, and location of woodland and bushveld- Bush-Clump & Tall Fynbos’ land-cover Swaziland and Lesotho, allows for the first type vegetation categories defined within classes were used in the comparison with time a comparison to be made on a national scale between the current and potential the NLC data, and the equivalent the DEAT defined ‘Savanna Biome’. The distribution of ‘natural’ vegetation resources. ‘Savanna Biome’ class defined within the inclusion of the NLC’s ‘Thicket, Bushland This article compares the distribution and DEAT’s ‘VegetationMap’ data. -

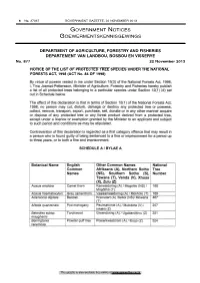

National Forests Act: List of Protected Tree Species

6 No. 37037 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 22 NOVEMBER 2013 GOVERNMENT NOTICES GOEWERMENTSKENNISGEWINGS DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE, FORESTRY AND FISHERIES DEPARTEMENT VAN LANDBOU, BOSBOU EN VISSERYE No. 877 22 November 2013 NOTICE OFOF THETHE LISTLIST OFOF PROTECTEDPROTECTED TREE TREE SPECIES SPECIES UNDER UNDER THE THE NATIONAL NATIONAL FORESTS ACT, 19981998 (ACT(ACT NO No. 84 84 OF OF 1998) 1998) By virtue of powers vested in me under Section 15(3) of the National Forests Act, 1998, I, Tina Joemat-Pettersson, Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries hereby publish a list of all protected trees belonging to a particular species under Section 12(1) (d) set out in Schedule below. The effect of this declaration is that in terms of Section 15(1) of the National Forests Act, 1998, no person may cut, disturb, damage or destroy any protected tree or possess, collect, remove, transport, export, purchase, sell, donate or in any other manner acquire or dispose of any protected tree or any forest product derived from a protected tree, except under a licence or exemption granted by the Minister to an applicant and subject to such period and conditions as may be stipulated. Contravention of this declaration is regarded as a first category offence that may result in a person who is found guilty of being sentenced to a fine or imprisonment for a period up to three years, or to both a fine and imprisonment. SCHEDULE A / BYLAE A Botanical Name English Other Common Names National Common Afrikaans (A), Northern SothoTree Names (NS),SouthernSotho (S),Number Tswana (T), Venda (V), Xhosa (X), Zulu (Z) Acacia erioloba Camel thorn Kameeldoring (A) / Mogohlo (NS) / 168 Mogotlho (T) Acacia haematoxylon Grey camel thorn Vaalkameeldoring (A) / Mokholo (T) 169 Adansonia digitata Baobab Kremetart (A) /Seboi (NS)/ Mowana 467 (T) Afzelia quanzensis Pod mahogany Peulmahonie (A) / Mutokota (V) / 207 lnkehli (Z) Balanites subsp. -

Water for Food and Ecosystems in the Baviaanskloof Mega Reserve Land and Water Resources Assessment in the Baviaanskloof, Easter

Water for Food and Ecosystems in the Baviaanskloof Mega Reserve Land and water resources assessment in the Baviaanskloof, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa H.C. Jansen Alterra-report 1812 Alterra, Wageningen, 2008 ABSTRACT Jansen, H.C., 2008. Walerfor bood and hicosystems in the baviaanskloofMega Reserve. IMnd and water resources assessment in the Baviaanskloof,Hastern Cape Province, South Africa. Wageningen, Alterra, Alterra-report 1812. 80 pages; 21 figs.; 6 tables.; 18 refs. This report describes the results of the land and water assessment for the project 'Water for Food and Ecosystems in the Baviaanskloof Mega Reserve'. Aim of the project is to conserve the biodiversity in a more sustainable way, by optimizing water for ecosystems, agricultural and domestic use, in a sense that its also improving rural livelihoods in the Baviaanskloof. In this report an assessment of the land and water system is presented, which forms a basis for the development and implementation of land and water policies and measures. Keywords: competing claims, IWRM, land management, nature conservation, policy support, water management, water retention ISSN 1566-7197 The pdf file is tree of charge and can he downloaded vi«i the website www.ahctra.wur.nl (go lo Alterra reports). Alterra docs not deliver printed versions ol the Altena reports. Punted versions can be ordered via the external distributor. I-or oidcrmg have a look at www.li tx> ni l) ljtl.nl/mppcirtc ilser vice . © 2008 Alterra P.O. Box 47; 6700 AA Wageningen; The Netherlands Phone: + 31 317 484700; fax: +31 317 419000; e-mail: info.alterra@,wur.nl No part of this publication may be reproduced or published in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system without the written permission of Alterra. -

Misgund Orchards

MISGUND ORCHARDS ENVIRONMENTAL AUDIT 2014 Grey Rhebok Pelea capreolus Prepared for Mr Wayne Baldie By Language of the Wilderness Foundation Trust In March 2002 a baseline environmental audit was completed by Conservation Management Services. This foundational document has served its purpose. The two (2) recommendations have been addressed namely; a ‘black wattle control plan’ in conjunction with Working for Water Alien Eradication Programme and a survey of the fish within the rivers was also addressed. Furthermore updated species lists have resulted (based on observations and studies undertaken within the region). The results of these efforts have highlighted the significance of the farm Misgund Orchards and the surrounds, within the context of very special and important biodiversity. Misgund Orchards prides itself with a long history of fruit farming excellence, and has strived to ensure a healthy balance between agricultural priorities and our environment. Misgund Orchards recognises the need for a more holistic and co-operative regional approach towards our environment and needs to adapt and design a more sustainable approach. The context of Misgund Orchards is significant, straddling the protected areas Formosa Forest Reserve (Niekerksberg) and the Baviaanskloof Mega Reserve. A formidable mountain wilderness with World Heritage Status and a Global Biodiversity Hotspot (See Map 1 overleaf). Rhombic egg eater Dasypeltis scabra MISGUND ORCHARDS Langkloof Catchment MAP 1 The regional context of Misgund Orchards becomes very apparent, where the obvious strategic opportunity exists towards creating a bridge of corridors linking the two mountain ranges Tsitsikamma and Kouga (south to north). The environmental significance of this cannot be overstated – essentially creating a protected area from the ocean into the desert of the Klein-karoo, a traverse of 8 biomes, a veritable ‘garden of Eden’. -

212Asparagus Workshop Part1.Indd

Plant Protection Quarterly Vol.21(2) 2006 63 National Asparagus Weeds Management Workshop Proceedings of a workshop convened by the National Asparagus Weeds Management Committee held in Adelaide on 10–11 November 2005. Editors: John G. Virtue and John K. Scott. Introduction John G. VirtueA and John K. ScottB A Department of Water Land and Biodiversity Conservation, GPO Box 2834, Adelaide, South Australia 5001, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] B CSIRO Entomology, Private Bag 5, PO Wembley, Western Australia 6913, Australia. Welcome to this special issue of Plant Pro- The National Asparagus Weeds Man- authors for the effort they have put into tection Quarterly, which details the current agement Committee (NAWMC) convened their papers and all the workshop par- state of Asparagus weeds management in the National Asparagus Weeds Manage- ticipants for their contribution. A special Australia. Bridal creeper, Asparagus as- ment Workshop in Adelaide, 10–11 No- thanks for workshop organization also paragoides (L.) Druce, is the best known vember 2005. The workshop was attended goes to Dennis Gannaway and Susan Asparagus weed and certainly deserves by 60 people including representation ex- Lawrie. its Weed of National Signifi cance (WoNS) tending from South Africa, through most status in Australia. However, there are regions of continental Australia, to Lord Reference other Asparagus species in Australia that Howe Island in the Pacifi c. The workshop Agriculture & Resource Management have the potential to reach similar levels was made possible with funding assistance Council of Australia & New Zealand, of impact as bridal creeper on biodiversity through the Australian Government’s Nat- Australia & New Zealand Environment (and hence their inclusion in the national ural Heritage Trust. -

Amathole District Municipality

AMATHOLE DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY 2012 - 2017 INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN Amathole District Municipality IDP 2012-2017 – Version 1 of 5 Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENT The Executive Mayor’s Foreword 4 Municipal Manager’s Message 5 The Executive Summary 7 Report Outline 16 Chapter 1: The Vision 17 Vision, Mission and Core Values 17 List of Amathole District Priorities 18 Chapter 2: Demographic Profile of the District 31 A. Introduction 31 B. Demographic Profile 32 C. Economic Overview 38 D. Analysis of Trends in various sectors 40 Chapter 3: Status Quo Assessment 42 1 Local Economic Development 42 1.1 Economic Research 42 1.2 Enterprise Development 44 1.3 Cooperative Development 46 1.4 Tourism Development and Promotion 48 1.5 Film Industry 51 1.6 Agriculture Development 52 1.7 Heritage Development 54 1.8 Environmental Management 56 1.9 Expanded Public Works Program 64 2 Service Delivery and Infrastructure Investment 65 2.1 Water Services (Water & Sanitation) 65 2.2 Solid Waste 78 2.3 Transport 81 2.4 Electricity 2.5 Building Services Planning 89 2.6 Health and Protection Services 90 2.7 Land Reform, Spatial Planning and Human Settlements 99 3 Municipal Transformation and Institutional Development 112 3.1 Organizational and Establishment Plan 112 3.2 Personnel Administration 124 3.3 Labour Relations 124 3.4 Fleet Management 127 3.5 Employment Equity Plan 129 3.6 Human Resource Development 132 3.7 Information Communication Technology 134 4 Municipal Financial Viability and Management 136 4.1 Financial Management 136 4.2 Budgeting 137 4.3 Expenditure -

Amathole District Municipality WETLAND REPORT | 2017

AMATHOLE DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY WETLAND REPORT | 2017 LOCAL ACTION FOR BIODIVERSITY (LAB): WETLANDS SOUTH AFRICA Biodiversity for Life South African National Biodiversity Institute Full Program Title: Local Action for Biodiversity: Wetland Management in a Changing Climate Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID/Southern Africa Cooperative Agreement Number: AID-674-A-14-00014 Contractor: ICLEI – Local Governments for Sustainability – Africa Secretariat Date of Publication: June 2017 DISCLAIMER: The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. FOREWORD Amathole District Municipality is situated within the Amathole District Municipality is also prone to climate central part of the Eastern Cape Province, which lies change and disaster risk such as wild fires, drought in the southeast of South Africa and borders the and floods. Wetland systems however can be viewed Indian Ocean. Amathole District Municipality has as risk reduction ecological infrastructure. Wetlands a land area of 21 595 km² with approximately 200 also form part of the Amathole Mountain Biosphere km of coastline stretching along the Sunshine Coast Reserve, which is viewed as a conservation and from the Fish River to just south of Hole in the Wall sustainable development flagship initiative. along the Wild Coast. Amathole District Municipality coastline spans two bio-geographical regions, namely Amathole District Municipality Integrated the warm temperate south coast and the sub-tropical Development Plan (IDP) recognises the importance east coast. of wetlands within the critical biodiversity areas of the Spatial Development Framework (SDF). Amathole District Municipality is generally in a good Sustainable development principles are an natural state; 83.3% of land comprises of natural integral part of Amathole District Municipality’s areas, whilst only 16.7% are areas where no natural developmental approach as they are captured in the habitat remains. -

Impact of Ethnobotanical Utilization on the Population Structure of Androstachys Johnsonii Prain

Bakali et al. Insights For Res 2017, 1(1):50-56 DOI: 10.36959/948/461 | Volume 1 | Issue 1 Insights of Forest Research Research Article Open Access Impact of Ethnobotanical Utilization on the Population Structure of Androstachys Johnsonii Prain. in the Vhembe Area of the Limpopo Province, South Africa Bakali M1, Ligavha-Mbelengwa MH1, Potgieter MJ2 and Tshisikhawe MP1* 1Department of Botany, University of Venda, South Africa 2Department of Biodiversity, University of Limpopo, Sovenga, South Africa Abstract Due to high levels of impoverishment, rural communities in southern African are highly dependent on their surroundings to sustain their livelihood. However, the rampant harvesting of Androstachys johnsonii Prain. In Vhembe area is a cause for concern although its conservation status is of Least Concern. Androstachys johnsonii is a tree species used for a variety of purposes in the Vhembe Area of South Africa to maintain households. Thus in order to obtain baseline data to propose ways of preserving the species, an investigation was launched to determine the extent of usage of A. johnsonii at Matshena village and document its population structure via stem size classes, crown health and plant height classes. Results indicate that this tree species is being used for a variety of purposes by inhabitants, with 65% of trees surveyed showing signs of harvesting. Due to its extremely durable hardwood this species is mostly used for fencing, roofing, pillar construction, and as firewood. Additional ethnobotanical uses include fodder for goats and cattle and medicinal purposes. Of the 353 A. john- sonii trees measured, the majority (27%) are in the 0-10 cm stem size class, and nearly 88% are lower than 5 m in height. -

Know Your National Parks

KNOW YOUR NATIONAL PARKS 1 KNOW YOUR NATIONAL PARKS KNOW YOUR NATIONAL PARKS Our Parks, Our Heritage Table of contents Minister’s Foreword 4 CEO’s Foreword 5 Northern Region 8 Marakele National Park 8 Golden Gate Highlands National Park 10 Mapungubwe National Park and World Heritage site 11 Arid Region 12 Augrabies Falls National Park 12 Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park 13 Mokala National Park 14 Namaqua National Park 15 /Ai/Ais-Richtersveld Transfrontier Park 16 Cape Region 18 Table Mountain National Park 18 Bontebok National Park 19 Agulhas National Park 20 West Coast National Park 21 Tankwa-Karoo National Park 22 Frontier Region 23 Addo Elephant National Park 23 Karoo National Park 24 DID YOU Camdeboo National Park 25 KNOW? Mountain Zebra National Park 26 Marakele National Park is Garden Route National Park 27 found in the heart of Waterberg Mountains.The name Marakele Kruger National Park 28 is a Tswana name, which Vision means a ‘place of sanctuary’. A sustainable National Park System connecting society Fun and games 29 About SA National Parks Week 31 Mission To develop, expand, manage and promote a system of sustainable national parks that represent biodiversity and heritage assets, through innovation and best practice for the just and equitable benefit of current and future generation. 2 3 KNOW YOUR NATIONAL PARKS KNOW YOUR NATIONAL PARKS Minister’s Foreword CEO’s Foreword We are blessed to live in a country like ours, which has areas by all should be encouraged through a variety of The staging of SA National Parks Week first took place been hailed as a miracle in respect of our transition to a programmes. -

The Ecology of Large Herbivores Native to the Coastal Lowlands of the Fynbos Biome in the Western Cape, South Africa

The ecology of large herbivores native to the coastal lowlands of the Fynbos Biome in the Western Cape, South Africa by Frans Gustav Theodor Radloff Dissertation presented for the degree of Doctor of Science (Botany) at Stellenbosh University Promoter: Prof. L. Mucina Co-Promoter: Prof. W. J. Bond December 2008 DECLARATION By submitting this dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the owner of the copyright thereof (unless to the extent explicitly otherwise stated) and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: 24 November 2008 Copyright © 2008 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii ABSTRACT The south-western Cape is a unique region of southern Africa with regards to generally low soil nutrient status, winter rainfall and unusually species-rich temperate vegetation. This region supported a diverse large herbivore (> 20 kg) assemblage at the time of permanent European settlement (1652). The lowlands to the west and east of the Kogelberg supported populations of African elephant, black rhino, hippopotamus, eland, Cape mountain and plain zebra, ostrich, red hartebeest, and grey rhebuck. The eastern lowlands also supported three additional ruminant grazer species - the African buffalo, bontebok, and blue antelope. The fate of these herbivores changed rapidly after European settlement. Today the few remaining species are restricted to a few reserves scattered across the lowlands. This is, however, changing with a rapid growth in the wildlife industry that is accompanied by the reintroduction of wild animals into endangered and fragmented lowland areas. -

Insights from Microsporogenesis in Asparagales

EVOLUTION & DEVELOPMENT 9:5, 460–471 (2007) Constraints and selection: insights from microsporogenesis in Asparagales Laurent Penet,a,1,Ã Michel Laurin,b Pierre-Henri Gouyon,a,c and Sophie Nadota aLaboratoire Ecologie, Syste´matique et Evolution, Batiment 360, Universite´ Paris-Sud, 91405 Orsay Ce´dex, France bUMR CNRS 7179, Universite´ Paris 6FPierre & Marie Curie, 2 place Jussieu, Case 7077, 75005 Paris, France cMuse´um National d’Histoire Naturelle, De´partement de Syste´matique et Evolution Botanique, 12 rue Buffon, 75005 Paris CP 39, France ÃAuthor for correspondence (email: [email protected]) 1Current address: Department of Biological Sciences, University of Pittsburgh, 4249 Fifth & Ruskin, Pittsburgh, PA 15260, USA. SUMMARY Developmental constraints have been proposed different characteristics of microsporogenesis, only cell to interfere with natural selection in limiting the available wall formation appeared as constrained. We show that set of potential adaptations. Whereas this concept has constraints may also result from biases in the correlated long been debated on theoretical grounds, it has been occurrence of developmental steps (e.g., lack of successive investigated empirically only in a few studies. In this article, cytokinesis when wall formation is centripetal). We document we evaluate the importance of developmental constraints such biases and their potential outcomes, notably the during microsporogenesis (male meiosis in plants), with an establishment of intermediate stages, which allow emphasis on phylogenetic patterns in Asparagales. Different development to bypass such constraints. These insights are developmental constraints were tested by character discussed with regard to potential selection on pollen reshuffling or by simulated distributions. Among the morphology. INTRODUCTION 1991) also hindered tests using the concept (Pigliucci and Kaplan 2000). -

Pollen Ultrastructure of the Biovulate Euphorbiaceae Author(S): Michael G

Pollen Ultrastructure of the Biovulate Euphorbiaceae Author(s): Michael G. Simpson and Geoffrey A. Levin Reviewed work(s): Source: International Journal of Plant Sciences, Vol. 155, No. 3 (May, 1994), pp. 313-341 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2475184 . Accessed: 26/07/2012 14:35 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to International Journal of Plant Sciences. http://www.jstor.org Int.J. Plant Sci. 155(3):313-341.1994. ? 1994by The Universityof Chicago. All rightsreserved. 1058-5893/94/5503-0008$02.00 POLLENULTRASTRUCTURE OF THE BIOVULATE EUPHORBIACEAE MICHAEL G. SIMPSON AND GEOFFREY A. LEVIN' Departmentof Biology,San Diego StateUniversity, San Diego,California 92182-0057; and BotanyDepartment, San Diego NaturalHistory Museum, P.O. Box 1390,San Diego,California 92112 Pollenultrastructure of the biovulate Euphorbiaceae, including the subfamilies Phyllanthoideae and Oldfieldioideae,was investigatedwith light, scanning electron, and transmissionelectron microscopy. Pollenof Phyllanthoideae, represented by 12 speciesin ninegenera, was prolateto oblate,almost always 3-colporate,rarely 3-porate or pantoporate,and mostlywith reticulate, rarely baculate, echinate, or scabrate,sculpturing.