Building Bridges Bok.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resources Concerning the History of Polish Jews in Castle Court Records of the 17Th and 18Th Centuries in the Central State Historical Archives in Kyiv and Lviv

SCRIPTA JUDAICA CRACOVIENSIA Vol. 18 (2020) pp. 127–140 doi:10.4467/20843925SJ.20.009.13877 www.ejournals.eu/Scripta-Judaica-Cracoviensia Resources Concerning the History of Polish Jews in Castle Court Records of the 17th and 18th Centuries in the Central State Historical Archives in Kyiv and Lviv Przemysław Zarubin https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4845-0839 (Jagiellonian University in Krakow, Poland) e-mail: [email protected] Keywords: archival sources, Ukraine, Lviv, Kyiv, castle court, 17th century, 18th century Abstract: The article presents types of sources which have thus far not been used, castle court books kept in the archives of the Ukrainian cities of Lviv and Kyiv. The author emphasizes the importance of these sources for research on the history and culture of Polish Jews in the 17th and 18th centuries. He also specifies the types of documents related to Jewish issues authenticated in these books (e.g. manifestations and lawsuits, declarations of the Radom Tribunal), as well as current source publications and internet databases containing selected documents from Ukrainian archives. The Central State Historical Archive in Lviv (CDIAL) (known as the Bernadine Ar- chive) and the Central State Historical Archive in Kyiv (CDIAUK) both have exten- sive collections of records of the so-called castle courts (sądy grodzkie), also known as local Starost courts (sądy starościńskie) for the nobility: from the Bełz and Ruthe- nian Voivodeships in the Lviv archive; and from the Łuck, Podolia, Kyiv, and Bracław Voivodeships in the Kyiv archive. This is particularly important because – in the light of Jewish population counts taken in 1764–1765 for the purpose of poll tax assessment – these areas were highly populated by Jews. -

Polish Battles and Campaigns in 13Th–19Th Centuries

POLISH BATTLES AND CAMPAIGNS IN 13TH–19TH CENTURIES WOJSKOWE CENTRUM EDUKACJI OBYWATELSKIEJ IM. PŁK. DYPL. MARIANA PORWITA 2016 POLISH BATTLES AND CAMPAIGNS IN 13TH–19TH CENTURIES WOJSKOWE CENTRUM EDUKACJI OBYWATELSKIEJ IM. PŁK. DYPL. MARIANA PORWITA 2016 Scientific editors: Ph. D. Grzegorz Jasiński, Prof. Wojciech Włodarkiewicz Reviewers: Ph. D. hab. Marek Dutkiewicz, Ph. D. hab. Halina Łach Scientific Council: Prof. Piotr Matusak – chairman Prof. Tadeusz Panecki – vice-chairman Prof. Adam Dobroński Ph. D. Janusz Gmitruk Prof. Danuta Kisielewicz Prof. Antoni Komorowski Col. Prof. Dariusz S. Kozerawski Prof. Mirosław Nagielski Prof. Zbigniew Pilarczyk Ph. D. hab. Dariusz Radziwiłłowicz Prof. Waldemar Rezmer Ph. D. hab. Aleksandra Skrabacz Prof. Wojciech Włodarkiewicz Prof. Lech Wyszczelski Sketch maps: Jan Rutkowski Design and layout: Janusz Świnarski Front cover: Battle against Theutonic Knights, XVI century drawing from Marcin Bielski’s Kronika Polski Translation: Summalinguæ © Copyright by Wojskowe Centrum Edukacji Obywatelskiej im. płk. dypl. Mariana Porwita, 2016 © Copyright by Stowarzyszenie Historyków Wojskowości, 2016 ISBN 978-83-65409-12-6 Publisher: Wojskowe Centrum Edukacji Obywatelskiej im. płk. dypl. Mariana Porwita Stowarzyszenie Historyków Wojskowości Contents 7 Introduction Karol Olejnik 9 The Mongol Invasion of Poland in 1241 and the battle of Legnica Karol Olejnik 17 ‘The Great War’ of 1409–1410 and the Battle of Grunwald Zbigniew Grabowski 29 The Battle of Ukmergė, the 1st of September 1435 Marek Plewczyński 41 The -

Rocznik Lituanistyczny Tom 6-2020.Indd

„ROCZNIK LITUANISTYCZNY” 6 ■ 2020 Witalij Michałowski https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0273-3668 Kijowski Uniwersytet im. Borysa Grinczenki Posłowie ruskich województw Korony na sejmie lubelskim w styczniu–lutym 1569 roku Zarys treści W artykule omówiono stosunek szlachty z ruskich województw Korony Polskiej (ruskiego, podol- skiego i bełskiego) na sejmie lubelskim w styczniu–lutym 1569 r. wobec planów unii, przed podjęciem decyzji o inkorporacji Podlasia i Wołynia. Abstrakt Th is article presents the stance taken by the representatives of the Ruthenian voievodeships of the Polish Crown (Ruthenian, Podolian, and Belz voivodeships) at the Sejm session in Lublin in 1569 before the incorporation of Podlasie and Volhynia. Słowa kluczowe: unia lubelska, sejm lubelskie 1569 r., województwa ruskie Korony, województwo ruskie, województwo podolskie, województwo bełskie Keywords: Union of Lublin, Lublin Sejm of 1569, Ruthenian voivodeships of the Polish Crown, Ruthenian voivodeship, Podolian voivodeship, Belz voivodeship Początkowe debaty na sejmie unijnym w Lublinie w styczniu–lutym 1569 r., do momentu wyjazdu posłów litewskich w nocy z 28 lutego na 1 marca, poka- zały postawy szlachty koronnej wobec unii. Strony koronna i litewska przed- stawiały niejednokrotnie swoją wizję utworzenia wspólnego państwa. Czasem dyskusje te przypominały „błędne koło”. Te same postulaty i odwołania do dziejów z 1501 r., które nazywano „za Alexandra”, oraz do recesu sejmu war- szawskiego z 1563/1564 r., właściwie nie wnosiły nic nowego to tematu. Dały one jednak szlachcie -

Eastern Europe - Historical Glossary

EASTERN EUROPE - HISTORICAL GLOSSARY Large numbers of people now living in western Europe, north and south America, South Africa and Australia are from families that originated in eastern Europe. As immigrants, often during the late 19th century, their origin will have been classified by immigration officials and census takers according to the governing power of the European territory from which they had departed. Thus many were categorised as Russian, Austrian or German who actually came from provinces within those empires which had cultures and long histories as nations in their own right. In the modern world, apart from Poland and Lithuania, most of these have become largely unknown and might include Livonia, Courland, Galicia, Lodomeria, Volhynia, Bukovina, Banat, Transylvania, Walachia, Moldavia and Bessarabia. During the second half of the 20th century, the area known as "Eastern Europe" largely comprised the countries to the immediate west of the Soviet Union (Russia), with communist governments imposed or influenced by Russia, following occupation by the Russian "Red Army" during the process of defeating the previous military occupation of the German army in 1944-45. Many of these countries had experienced a short period of independence (1918-1939) between the two World Wars, but before 1918 most of the territory had been within the three empires of Russia, Austria-Hungary and Ottoman Turkey. The Ottoman empire had expanded from Turkey into Europe during the 14th-15th centuries and retained control over some territories until 1918. The commonwealth of Poland and Lithuania was established in the 16th century and for two centuries ruled over the territories north of Hungary, while the Ottoman empire ruled over those to the south, but between 1721-1795 the Russian empire took control of the Baltic states and eastern Poland and during a similar period Austria-Hungary took control of southern Poland and the northern and western territories of the Ottoman empire. -

Synagogues in Podkarpacie – Prolegomenon to Research

TECHNICAL TRANSACTIONS 9/2019 ARCHITECTURE AND URBAN PLANNING DOI: 10.4467/2353737XCT.19.092.10874 SUBMISSION OF THE FINAL VERSION: 30/07/2019 Dominika Kuśnierz-Krupa orcid.org/0000-0003-1678-4746 [email protected] Faculty of Architecture, Cracow University of Technology Lidia Tobiasz AiAW Design Office Lidia Tobiasz Synagogues in Podkarpacie – prolegomenon to research Synagogi Podkarpacia – prolegomena do badań Abstract This paper is a prolegomenon to the research on the history, architecture and state of preservation of the synagogues still surviving in the Podkarpacie region. After almost a millennium of Jewish presence in the area, despite wars and the Holocaust, 31 buildings or the ruins of former synagogues have remained until the present. It can be claimed that a Jewish cultural heritage of considerable value has survived in the Podkarpacie region to this day, and therefore requires protection and revalorisation. The paper presents the state of research in this area and an outline of the Jewish history of Podkarpacie, as well as a preliminary description of the preserved synagogues with regards to their origin, functional layout and state of preservation. Keywords: Podkarpacie region, synagogues, history, state of preservation Streszczenie Niniejszy artykuł jest prolegomeną do badań nad historią, architekturą oraz stanem zachowania istniejących jeszcze na terenie Podkarpacia synagog. Z prawie tysiącletniej obecności Żydów na tym terenie, pomimo wojen i zagłady, do dnia dzisiejszego pozostało 31 budynków lub ich ruin, w których kiedyś mieściły się synagogi. Można zatem stwierdzić, że do dzisiaj zasób zabytkowy kultury żydowskiej na Podkarpaciu jest pokaźny, a co za tym idzie, wymagający ochrony i rewaloryzacji. -

Application of Link Integrity Techniques from Hypermedia to the Semantic Web

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON Faculty of Engineering and Applied Science Department of Electronics and Computer Science A mini-thesis submitted for transfer from MPhil to PhD Supervisor: Prof. Wendy Hall and Dr Les Carr Examiner: Dr Nick Gibbins Application of Link Integrity techniques from Hypermedia to the Semantic Web by Rob Vesse February 10, 2011 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF ENGINEERING AND APPLIED SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF ELECTRONICS AND COMPUTER SCIENCE A mini-thesis submitted for transfer from MPhil to PhD by Rob Vesse As the Web of Linked Data expands it will become increasingly important to preserve data and links such that the data remains available and usable. In this work I present a method for locating linked data to preserve which functions even when the URI the user wishes to preserve does not resolve (i.e. is broken/not RDF) and an application for monitoring and preserving the data. This work is based upon the principle of adapting ideas from hypermedia link integrity in order to apply them to the Semantic Web. Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Hypothesis . .2 1.2 Report Overview . .8 2 Literature Review 9 2.1 Problems in Link Integrity . .9 2.1.1 The `Dangling-Link' Problem . .9 2.1.2 The Editing Problem . 10 2.1.3 URI Identity & Meaning . 10 2.1.4 The Coreference Problem . 11 2.2 Hypermedia . 11 2.2.1 Early Hypermedia . 11 2.2.1.1 Halasz's 7 Issues . 12 2.2.2 Open Hypermedia . 14 2.2.2.1 Dexter Model . 14 2.2.3 The World Wide Web . -

Acta Nuntiaturae Polonae

ACTA NUNTIATURAE POLONAE ACADEMIA SCIENTIARUM ET LITTERARUM POLONA SUMPTIBUS FUNDATIONIS LANCKOROŃSKI ACTA NUNTIATURAE POLONAE TOMUS LII ANGELUS MARIA DURINI (1767-1772) * Volumen 1 (12 IV 1766 – 20 IV 1768) edidit WOJCIECH KĘDER CRACOVIAE 2016 CONSILIUM EORUM, QUI EDITORIBUS ACTORUM NUNTIATURAE POLONAE SUADENT: Marco Jačov, Ioannes Kopiec, Iosephus Korpanty, Vanda Lohman, Marius Markiewicz, Anna Michalewicz (secretarius), Stanislaus Wilk, Georgius Wyrozumski (praeses) Volumen hoc edendum curavit Vanda Lohman Summaria, studia et fontes auxiliarii in linguam Anglorum vertit Petrus Pieńkowski Indicem confecit Krzysztof W. Zięba Textum ad imprimendum composuit MKBB © Copyright by Polska Akademia Umiejętności Kraków 2016 ISBN 978-83-7676-259-3 LIST OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................. VII I. Angelo Maria Durini’s early years in Rome and in France ............................................ VII II. Angelo Maria Durini in Warsaw ........................... X III. Angelo Maria Durini in Avignon and in Lombardy ........................................ XXVI Sources of Angelo Maria Durini’s Nunciature .................... XXIX Index of sources published in present volume .................... XXXIII Works which contain Angelo Maria Durini’s letters and documents ........................................... XXXV Primary and secondary sources ................................. XXXVII Index of notas ................................................. XLV TEXT ........................................................ 1 Index of names and places ...................................... 383 INTRODUCTION I. Angelo Maria Durini’s early years in Rome and in France 1. The Durini family of Como Angelo Maria Durini came from the family living in Lombardy and known already in the Middle Ages. Lazzaro de Durino, who apparently lived in the vicinity of the town of Moltrasio at Como Lake at the beginning of the 15th century, can be considered the family founder. In the seventies of the 15th century his son Teobaldo moved to Como with his children. -

Regional Identity and the Renewal of Spatial Administrative Structures: the Case of Podolia, Ukraine

MORAVIAN GEOGRAPHICAL REPORTS 2018, 26(1):2018, 42–54 26(1) Vol. 23/2015 No. 4 MORAVIAN MORAVIAN GEOGRAPHICAL REPORTS GEOGRAPHICAL REPORTS Institute of Geonics, The Czech Academy of Sciences journal homepage: http://www.geonika.cz/mgr.html Figures 8, 9: New small terrace houses in Wieliczka town, the Kraków metropolitan area (Photo: S. Kurek) doi: 10.2478/mgr-2018-0004 Illustrations to the paper by S. Kurek et al. Regional identity and the renewal of spatial administrative structures: The case of Podolia, Ukraine Anatoliy MELNYCHUK a, Oleksiy GNATIUK b * Abstract The relationships between territorial identities and administrative divisions are investigated in this article, in an attempt to reveal the possible role of territorial identity as an instrument for administrative-territorial reform. The study focuses on Podolia – a key Ukrainian geographical region with a long and complicated history. A survey of residents living throughout the region showed that the majority of respondents had developed strong identification with both historical regions and modern administrative units. The close interaction between “old” and “new” identities, however, caused their mutual alterations, especially in changes in the perceived borders of historical regions. This means that the “old” historical identities have strong persistence but simultaneously survive constant transformations, incorporating the so-called “thin” elements, which fits the concept of dynamic regional institutionalisation and the formation of hybrid territorial identities. Consequently, although territorial identity may be used to make administrative territorial units more comprehensible for people, the development of modern administrative units based on hybrid identities, which include both thick and thin elements, may be another feasible solution that involves stakeholders in regional development. -

43 Historical Oikonymy of the Western Ukraine in Common

GISAP PHILOLOGICAL SCIENCES Historical OIKONYMY OF THE WESTERN UKRAINE IN COMMON Slavic CONTEXT (AS EXEMPLIFIED BY THE EVOLUTION OF topoformant *-išče // *-ISKO IN Slavic LANGUAGES) Y. Redkva, Candidate of Philology, Associate Professor Chernivtsi National University named after Y. Fedkovych, Ukraine The historiacal - etymological analysis of archaic Slavic topoformant *-išče // *-isko, preserved in the oikonymy of Halych and Lviv Lands of the Ruthenian Voivodeship, is carried out. On the basis of oikonymic materials from the majority of Slavic territories appellative lexemes, that formed base for the emergence of settlements names both on analyzable territory and on Pan-Slavic territory, are reconstructed on Old Slavonic level. Presented mechanisms of formation of the historical oikonymy on the basis of reconstructed appellatives showed autochthony of the Slavic population, which has long been living on these territories. Keywords: oikonym, base appellative, toponym, formant, reconstruction of appellative form. Conference participants, National championship in scientific analytics, Open European and Asian research analytics championship roto Slavic suffixes *-išče // *-isko Western Ukrainian dialects is explained Slavic languages, partially in Ukrainian Phave long been the focus of studies by Polish influence [5, 175–183]. and Polish, and absent in southern Slavic by Slavic linguists as their proto Slavic F. Slawski believes that formant *-isko is languages. [1, 32]. Therefore we can genesis have not yet been established by connected to *-ьskъ (-ьsko), explaining argue that suffix -ище [-yshche] has its now. *-išče and -isko derivatives, their its origin from Proto Indo European Ukrainian equivalent of the suffix-исько , use on Pan-Slavic area, especially in *-ǐsko to denote adjectives with neutral similar to Polish where suffix -iszcze(a) eastern Slavic countries have not been and diminutive and pejorative meanings. -

Imaginations and Configurations of Polish Society. from the Middle

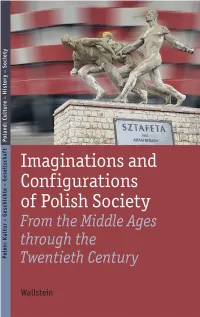

Imaginations and Configurations of Polish Society Polen: Kultur – Geschichte – Gesellschaft Poland: Culture – History – Society Herausgegeben von / Edited by Yvonne Kleinmann Band 3 / Volume 3 Imaginations and Configurations of Polish Society From the Middle Ages through the Twentieth Century Edited by Yvonne Kleinmann, Jürgen Heyde, Dietlind Hüchtker, Dobrochna Kałwa, Joanna Nalewajko-Kulikov, Katrin Steffen and Tomasz Wiślicz WALLSTEIN VERLAG Gedruckt mit Unterstützung der Deutsch-Polnischen Wissenschafts- stiftung (DPWS) und der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft (Emmy Noether- Programm, Geschäftszeichen KL 2201/1-1). Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. © Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2017 www.wallstein-verlag.de Vom Verlag gesetzt aus der Garamond und der Frutiger Umschlaggestaltung: Susanne Gerhards, Düsseldorf © SG-Image unter Verwendung einer Fotografie (Y. Kleinmann) von »Staffel«, Nationalstadion Warschau Lithografie: SchwabScantechnik, Göttingen ISBN (Print) 978-3-8353-1904-2 ISBN (E-Book, pdf) 978-3-8353-2999-7 Contents Acknowledgements . IX Note on Transliteration und Geographical Names . X Yvonne Kleinmann Introductory Remarks . XI An Essay on Polish History Moshe Rosman How Polish Is Polish History? . 19 1. Political Rule and Medieval Society in the Polish Lands: An Anthropologically Inspired Revision Jürgen Heyde Introduction to the Medieval Section . 37 Stanisław Rosik The »Baptism of Poland«: Power, Institution and Theology in the Shaping of Monarchy and Society from the Tenth through Twelfth Centuries . 46 Urszula Sowina Spaces of Communication: Patterns in Polish Towns at the Turn of the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Times . 54 Iurii Zazuliak Ius Ruthenicale in Late Medieval Galicia: Critical Reconsiderations . -

Issn 1691-3078 Isbn 978-9984-9937-2-0

ISSN 1691-3078 ISBN 978-9984-9937-2-0 Economic Science for Rural Development Nr. 19., 2009 1 ISSN 1691-3078 2 Economic Science for Rural Development Nr. 19, 2009 ISSN 1691-3078 “ECONOMIC SCIENCE FOR RURAL DEVELOPMENT” Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference PRIMARY AND SECONDARY PRODUCTION, CONSUMPTION № 19 Jelgava 2009 Economic Science for Rural Development Nr. 19., 2009 1 ISSN 1691-3078 L. Rantamäki-Lahtinen Turning Rural Potential into Success TIME SCHEDULE OF THE CONFERENCE: Preparation – September, 2008 – April 20, 2009 Process – April 23-24, 2009 ▪ Latvia University of Agriculture, 2009 ▪ West University of Timisoara, 2009 ▪ Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 2009 ▪ Technological Educational Institute of Thessaloniki, 2009 ▪ Georgian Subtropical Agricultural State University, 2009 ▪ Batumi Shota Rustaveli State University, 2009 ▪ University of Helsinki, 2009 ▪ Finnish Forest Research Institute, 2009 ▪ Swedish University of Agricultural Science, 2009 ▪ University of Latvia, 2009 ▪ Daugavpils University, 2009 ▪ University of Tartu, 2009 ▪ Estonian University of Life Sciences, 2009 ▪ Siauliai University, 2009 ▪ Lithuanian Institute of Agricultural Economics, 2009 ▪ Warsaw University of Life Sciences, 2009 ▪ Poznan University of Economics, 2009 ▪ Agricultural University of Szczecin, 2009 ▪ Kujawy and Pomorze University in Bydgoszcz, 2009 ▪ University of Zielona Góra, 2009 ▪ Fulda University of Applied Sciences, 2009 ▪ Rēzekne Higher School, 2009 ▪ Research Institute of Agriculture Machinery of Latvia University of -

Swot Analysis and Planning for Cross-Border Co-Operation in Northern Europe

Projet SWOT 2_Mise en page 1 24/02/10 11:36 Page1 SWOT 2 SWOT 2 Analysis and Planning for Cross-border Co-operation in Northern Europe This study is one in a series of three prepared by ISIG - Istituto di Sociologia Co-operation Europe Northern for Cross-border in Planning and Analysis Internazionale di Gorizia (Institute of International Sociology of Gorizia), Italy at the request of the Council of Europe. Its purpose is to provide a scientific assessment of the state of cross-border co-operation between European states in the geographical area of Northern Europe. It provides, among others, an overview of the geographic, economic, infrastructural and historic characteristics of the area and its inherent Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats (SWOT) for cross-border co-operation. Some strategies for action by the member states concerned are proposed. This study was financed by Lithuania. Institute of International Sociology ISIG Gorizia Swot Analysis and Planning for Cross-Border Co-operation in Northern Europe Prepared by Institute of International Sociology of Gorizia (ISIG) for the Council of Europe SERIES 1. Swot Analysis and Planning for Cross-border Co-operation in Central European Countries 2. Swot Analysis and Planning for Cross-border Co-operation in Northern Europe 3. Swot Analysis and Planning for Cross-border Co-operation in South Eastern Europe LEGAL DISCLAIMER: Although every care has been taken to ensure that the data collected are accurate, no responsibility can be accepted for the consequences of factual errors and inaccuracies. The views expressed in this document are those of its author and not those of the Council of Europe or any of its organs.