Volume 25, Number 04, September 2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dead Kennedys and the Yippie-Punk Continuum I Michael Stewart Foley

Political Pie-Throwing: Dead Kennedys and the Yippie-Punk Continuum i Michael Stewart Foley To cite this version: Michael Stewart Foley. Political Pie-Throwing: Dead Kennedys and the Yippie-Punk Continuum i. Sonic Politics: Music and Social Movements in the Americas, 2019, 1138389390. hal-01999010 HAL Id: hal-01999010 https://hal.univ-grenoble-alpes.fr/hal-01999010 Submitted on 30 Jan 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Political Pie-Throwing: Dead Kennedys and the Yippie-Punk Continuumi MICHAEL STEWART FOLEY By the time Dead Kennedys released their first LP, Fresh Fruit for Rotting Vegetables, in 1980, the band had established itself as the leading American political punk band, hailing from a city that seemed to specialize in political art. In many ways, the band and its music represented the culmination of nearly three years of subcultural political struggle on a host of issues facing not only young people in San Francisco but American youth everywhere – enough that, to this day, many of the city’s punk veterans refer to their experience in the “movement.” Political historians of the United States in the 1970s and 1980s have mostly ignored punk, but this essay examines Dead Kennedys’ early career as a way to illuminate the political experience of one segment of American youth in the late 1970s. -

Universitas Indonesia Perkembangan Musik Punk Di Amerika Serikat Tahun

UNIVERSITAS INDONESIA PERKEMBANGAN MUSIK PUNK DI AMERIKA SERIKAT TAHUN 1974-1980 SKRIPSI Diajukan sebagai salah satu syarat untuk memperoleh gelar Sarjana Humaniora AHMAD FIKRI HADI NPM 0704040017 FAKULTAS ILMU PENGETAHUAN BUDAYA PROGRAM STUDI SEJARAH DEPOK DESEMBER 2008 Perkembangan musik..., Ahmad Fikri Hadi, FIB UI, 2008 Universitas Indonesia HALAMAN ORISINALITAS Skripsi ini adalah hasil kerja saya sendiri, dan semua sumber baik yang dikutip maupun dirujuk telah saya nyatakan dengan benar. Nama : Ahmad Fikri Hadi NPM : 0704040017 Tanda Tangan : Tanggal : 31 Desember 2008 Perkembangan musik..., Ahmad Fikri Hadi, FIB UI, 2008 Universitas Indonesia HALAMAN PENGESAHAN Skripsi yang diajukan oleh Nama : Ahmad Fikri Hadi NPM : 0704040017 Program Studi : Sejarah Judul : Perkembangan Musik Punk Di Amerika Serikat Tahun 1974- 1980 Ini telah berhasil dipertahankan di hadapan Dewan Penguji dan diterima sebagai bagian persyaratan yang diperlukan untuk memperoleh gelar Sarjana Humaniora pada Program Studi Sejarah, Fakultas Ilmu Pengetahuan Budaya, Universitas Indonesia. DEWAN PENGUJI Pembimbing : Dr. Magdalia Alfian ( ) Pembimbing : Sudarini Suhartono, M.A. ( ) Penguji : Linda Sunarti, M.Hum. ( ) Penguji : Kasijanto Sastrodinomo, M.Hum. ( ) Ditetapkan di : Universitas Indonesia, Depok Tanggal : 31 Desember 2008 Oleh Dekan Fakultas Ilmu Pengetahuan Budaya Universitas Indonesia Perkembangan musik..., Ahmad Fikri Hadi, FIB UI, 2008 Universitas Indonesia KATA PENGANTAR Segala puji dan syukur yang tidak terhingga penulis ucapkan kepada Allah SWT, Tuhan semesta alam, yang telah memberikan kasih sayang, anugrah, cobaan dan bantuan- Nya sehingga skripsi ini berhasil diselesaikan tepat waktu. Skripsi ini disusun sebagai syarat kelulusan untuk mendapatkan gelar sarjana dari Program Studi Sejarah, Fakultas Ilmu dan Pengetahuan Budaya, Universitas Indonesia. Dalam skripsi ini penulis berusaha untuk meneliti perkembangan musik punk di Amerika Serikat. -

Bill Bailey Vs

TheOnce:ler Of L&Ytonville Bill Bailey Vs. TheLorax MnCity� The Death (Or Was It Murder?) Of Detroit Berlin: Now Let's Tear Down Some Of Our OwnWal ls EmeraldTriangle . & San Francisco News + Northern California Punk Rock: Tons of Totally Crucial Coverage Along WithPages And. Pages Of Insignificant Fluff, Gossip & Mondo DestructoReviews .. EBP-DA | www.eastbaypunkda.com � '-.;._ -� 'Jl t.\.,._�� �- 1· / E:T. -· -...,,,.. �--- ....__� -..._ . .l'. Adventure .., CIADru& Wars: The Continues economies of sever:tJ Latin :-';m :un�ies, an hanced much.l=- p eri�an co d fi h new development m US cities Miami, New , and Lofi--==- -..: Ietnam as O UCM un, et S L I hke York y· W S Angeles. It a1so helped the CIA 10 pursue its regime· of terrorism and. I Ullm'<n1ioo uom,d <h• globe. - D 0 t All Q Vef Agalll... • . ey If ��t trouble _lay ahead for the c ociiliie kmgpi'"iisofLangl , _ Virginia. Inspired by the ,American free enter system, _ Remember Vietnam? Probably not. you're a student, you/ prise If j thousands of entrepeneuni real.1zed that there was r00m them in might have heard about it in history class, which almost guarantees,, for -'I :- � the marketpl e. Anyone with the for a p lan et IO -- you don't have any idea what it was about. you're old enough, ac money e tick �� that �ogota and the cluitzpah to bl way :::,,,--- to have been around when it was happening, even if you were one ofl' . �ff his or her past customs ms to was on the way to t fortune. -

AND YOU WILL KNOW US Mistakes & Regrets .1-2-5 What

... AND YOU WILL KNOW US Mistakes & Regrets .1-2-5 What You Don't Know 10 COMMANDMENTS Not True 1989 100 FLOWERS The Long Arm Of The Social Sciences 100 FLOWERS The Long Arm Of The Social Sciences 100 WATT SMILE Miss You 15 MINUTES Last Chance For You 16 HORSEPOWER 16 Horsepower A&M 540 436 2 CD D 1995 16 HORSEPOWER Sackcloth'n'Ashes PREMAX' TAPESLEEVES PTS 0198 MC A 1996 16 HORSEPOWER Low Estate PREMAX' TAPESLEEVES PTS 0198 MC A 1997 16 HORSEPOWER Clogger 16 HORSEPOWER Cinder Alley 4 PROMILLE Alte Schule 45 GRAVE Insurance From God 45 GRAVE School's Out 4-SKINS One Law For Them 64 SPIDERS Bulemic Saturday 198? 64 SPIDERS There Ain't 198? 99 TALES Baby Out Of Jail A GLOBAL THREAT Cut Ups A GUY CALLED GERALD Humanity A GUY CALLED GERALD Humanity (Funkstörung Remix) A SUBTLE PLAGUE First Street Blues 1997 A SUBTLE PLAGUE Might As Well Get Juiced A SUBTLE PLAGUE Hey Cop A-10 Massive At The Blind School AC 001 12" I 1987 A-10 Bad Karma 1988 AARDVARKS You're My Loving Way AARON NEVILLE Tell It Like It Is ABBA Ring Ring/Rock'n Roll Band POLYDOR 2041 422 7" D 1973 ABBA Waterloo (Swedish version)/Watch Out POLYDOR 2040 117 7" A 1974 ABDELLI Adarghal (The Blind In Spirit) A-BONES Music Minus Five NORTON ED-233 12" US 1993 A-BONES You Can't Beat It ABRISS WEST Kapitalismus tötet ABSOLUTE GREY No Man's Land 1986 ABSOLUTE GREY Broken Promise STRANGE WAYS WAY 101 CD D 1995 ABSOLUTE ZEROS Don't Cry ABSTÜRZENDE BRIEFTAUBEN Das Kriegen Wir schon Hin AU-WEIA SYSTEM 001 12" D 1986 ABSTÜRZENDE BRIEFTAUBEN We Break Together BUCKEL 002 12" D 1987 ABSTÜRZENDE -

© TSUNAMI EDIZIONI - RIPRODUZIONE RISERVATA Dell’Articolo 10Dellaconvenzione Diberna

LE TEMPESTE 23 © TSUNAMI EDIZIONI - RIPRODUZIONE RISERVATA Copyright © 2019 A.SE.FI. Editoriale Srl – Via dell’Aprica, 8 – Milano www.tsunamiedizioni.com – [email protected] – Twitter e Instagram: @tsunamiedizioni Prima edizione Tsunami Edizioni, luglio 2020 – Le Tempeste 23 Tsunami Edizioni è un marchio registrato di A.SE.FI. Editoriale Srl Le fotogra e di Dead Kennedys (pagg. 33, 34, 35 e 64) e Robbie Fields (pagg. 129 e 131) sono di Federico Gugliel- mi. Tutte le altre sono immagini promozionali raccolte nel corso degli anni dallo stesso autore. Foto di copertina: Bad Religion dal vivo alla Sala Razzmatazz di Barcellona il 18 giugno 2008. ©Alterna2 - www.alterna2.com - www. ickr.com/photos/alterna2 Foto di retrocopertina: Jello Biafra And e Guantanamo School Of Medicine dal vivo all'Astra di Berlino il 29 luglio 2011. ©Montecruz Foto - www.montecruzfoto.org - [email protected] - www. ickr.com/photos/ libertinus Le foto di copertina e retrocopertina sono usate e accreditate rispettivamente secondo licenza Creative Commons "Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0)" e "Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-SA 2.0)", fonte Flickr. Ogni modi ca alle foto originali è invece da attribuire ad Agenzia Alcatraz. Stampa Geca Industrie Gra che, San Giuliano Milanese, con sistema Rotobook. Giugno 2020 ISBN: 978-88-94859-38-6 Tutte le opinioni espresse in questo libro sono dell’autore e/o dell’artista, e non rispecchiano necessariamente quelle dell’Editore. Tutti i diritti riservati. È vietata la riproduzione, anche parziale, in qualsiasi formato, senza l’autorizzazione scritta dell’Editore. La presente opera di saggistica è pubblicata con lo scopo di rappresentare un’analisi critica, rivolta alla promozione di autori e opere di ingegno, che si avvale del diritto di citazione. -

Music Theater Books

38 CHICAGO READER | DECEMBER 9, 2005 | SECTION ONE Reviews Music Theater Books Anniversary reissues from Bruce Springsteen Old Clown and the Wanted Sprawl: Dead Kennedys at Trap Door ACompact REVIEW BY MONICAKENDRICK Theatre History REVIEW BY JUSTIN HAYFORD by Robert a Bruegmann 38 REVIEW BY HAROLD HENDERSON 40 42 T CHAPPELL a a Y KIT SALL Music DEAD KENNEDYS FRESH FRUIT FOR ROTTING VEGETABLES: SPECIAL 25TH ANNIVERSARY EDITION CD + DVD (MANIFESTO) BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN BORN TO RUN: 30TH ANNIVERSARY 3 DISC SET (COLUMBIA) It’s the Economics, Stupid What could Bruce Springsteen and the Dead Kennedys possibly have in common? By Monica Kendrick t’s a little jarring to be reminded now that these two I era-defining albums—which seem to lie on either side of a generation gap the size of Snake River Canyon—came out only five years apart. But if you were at an impressionable age in 1975, when Bruce Springsteen released Born to Run, or in 1980, when the Dead Kennedys put out Fresh Fruit for Rotting Vegetables, chances are those five years made all the difference in the world. Relative age matters TEEN) more the younger you are. I mean, do you feel the same way now about dating someone five years older as you did when you were 15? I turned 6 and 11 the years PETER CUNNINGHAM (SPRINGS they were originally released— Dead Kennedys circa 1980, Bruce Springsteen circa 1975 my dad even bought the Dead Kennedys record, bless him— trends, they still are. Somebody frustration and despair of the inside and a reproduction of ognize the Boss for his contri- and caught up with them both somewhere in the world is hear- working class in ways that have the original insert—a punk-ass butions to American culture. -

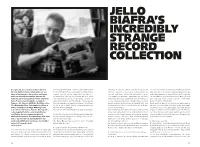

Jello Biafra's Incredibly Strange Record Collection

JELLO BIAFRa’S INCREDIBLY STRANGE RECORD COLLECTION Es ergab sich, dass ich über mehrere Wochen er nicht grade telefonierte, konnte ich seine Platten durch solltest du dir anhören!« Mit ein oder zwei Songs war für er auch schon herein! Ich war nicht vorbereitet auf diese rie- für Jello Biafra hackelte. Arbeitsplatz war sein das Haus schallen lassen – in extremer Lautstärke und Kon- mich klar: »Oh my God, this is the incredibly strangest mu- sige Hand, die er um meinen Hinterkopf legte und mir ge- Haus in San Francisco, das er schon seit langer sequenz. Legte ich eine rare Swans-Platte auf, dauerte es sic of all, right here!« »Rock’n’Roll McDonald’s« war die rade in die Augen starrte: »Say ra! RA!!« – bonk! Er gibt mir Zeit bewohnt und das aussieht, als wäre der nur Minuten, bis Jello mir, der ich gerade auf einer Stehlei- erste Nummer auf dem Tape. Tammy hatte das von unver- einen Headbutt. »Say row! ROW!« – bonk! Noch ein Head- Architekt auf Drogen gewesen: kleine Türmchen, ter herumschichtete, auf die Schulter klopfte und eine ob- öffentlichten DAT-Tapes zusammengestellt. Normalerweise butt. »Say ooga-booga! OOGA-BOOGA!« – bonk! Dann bunte Fenster, raue Felswände, verwinkelte skure Vinyl-Scheibe in die Hand drückte: »Kennst du die? ist es ja so mit Leuten, die heute »Outsider Artists« genannt lachte er herzhaft: »Hehehehe!« Treppen – die Szenerie wirkt wie die Kulisse eines Das sind sozusagen die japanischen Swans… irres Zeug!« werden: entweder drei, vier Songs sind wirklich wild – und Damit wusste er, dass ich ok mit ihm war. Später sagte er 70er Koksparty-Films. -

Dead Kennedys Punk Legends Rock the House of Blues Page 3

SEX: When one can be the loneliest number Full MOVIE: 'House of D' touches hearts and funny bones , MUSIC: Louis XIV love women, substance abuse EFFECTTitan Entertainment Guide Dead Kennedys Punk legends rock the House of Blues Page 3 Style scouts debate over fashion Boho VS. Hobo chic Page 7 A p r i l 2 1, 2 0 0 5 scheduled for late 2005 or early has cancelled the remaining dates 2006, but three songs have been on its current tour. According to CONTENTS completed of which one features the band, guitarist Paul Hinojos Compton rapper the Game… suffered a ruptured disc in his back Northern California band Dredg recently. No plans have been made have decided to release their next by the band to reschedule the can- 02 Entertainment Briefs—The Buzz album on June 21. Catch Without celled dates but plan to make up BY NIYAZ PIRANI 03 Music—Seasoned punks still Arms will feature the single “Bug for them on the next tour…After Daily Titan Assistant News Editor Eyes” which has been making months of speculation by tabloids standing strong quite a buzz on the Web…White as well as fans, Britney Spears is 04 Movie Review—'Horror remake Stripes members Jack and Meg offi cially pregnant. To watch the Limp Bizkit has slated a tenta- White are putting the fi nishing moments that led to conception, spooks with grotesque imagery tive May 3 release date for their touches on their June 7 release tune in to Spears and husband new album The Unquestionable Get Behind Me Satan. -

Identity, Ideological Conflict and the Field Of

“WHAT WAS ONCE REBELLION IS NOW CLEARLY JUST A SOCIAL SECT”: IDENTITY, IDEOLOGICAL CONFLICT AND THE FIELD OF PUNK ROCK ARTISTIC PRODUCTION A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the Department of Sociology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By M.D. DASCHUK Copyright Mitch Douglas Daschuk, August 2016. All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis/dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis/dissertation in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis/dissertation work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis/dissertation or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis/dissertation. DISCLAIMER The [name of company/corporation/brand name and website] were exclusively created to meet the thesis and/or exhibition requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Saskatchewan. Reference in this thesis/dissertation to any specific commercial products, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the University of Saskatchewan. -

The Deaf Club an Un-Oral History

The Deaf Club An Un-oral History ________________________________ This piece was originally published by Maximumrocknroll, the long-running fanzine that understood the historical importance of the venue that hosted two years’ worth of ribald punk music, art and performance, and underground films that have become an intrinsic portion of West Coast “year zero” lore. I am indebted to Kathy Peck of the Contractions, who was able to network me to old guard San Francisco punks. The piece is also dedicated to Olin Fortney, who was both deaf and punk—an actual Deaf Club member before the venue hosted shows. He befriended me in 2005 when we taught together in western Oregon and provided me with remarkable visual materials and anecdotes. He also embodied the spirit of the era so well. He died on my birthday in 2010, so I was unable to interview him for this oral history, which shames me to this day. I miss him profoundly. Ethan Davidson (fan) In 1978 or perhaps 1979, a lot of punks were getting fed up with Dirk Dirksen and the Mabuhay Gardens having a monopoly on punk shows. Some people didn’t like him, some didn’t agree that punk was a “theatre of the absurd.” Some simply wanted the community itself to have more control. We sought out alter- native venues and came up with one of the most interesting social experiments I’ve participated in—the Deaf Club. Nobody was famous, the shows were really cheap, and as soon as a band stopped playing, they got o¤ the stage and simply became part of the audi- © Ensminger, David, Jul 01, 2013, Left of the Dial : Conversations with Punk Icons PM Press, Oakland, ISBN: 9781604868883 ence. -

![CARRERA DE ESTUDIOS MUSICALES BOGOTÁ, JUNIO DE 2019 ASESORES: SANIAGO BOTERO, LUIS GUEVARA [Énfasis: Jazz Y Músicas Populares: Bajo Eléctrico]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3685/carrera-de-estudios-musicales-bogot%C3%A1-junio-de-2019-asesores-saniago-botero-luis-guevara-%C3%A9nfasis-jazz-y-m%C3%BAsicas-populares-bajo-el%C3%A9ctrico-8953685.webp)

CARRERA DE ESTUDIOS MUSICALES BOGOTÁ, JUNIO DE 2019 ASESORES: SANIAGO BOTERO, LUIS GUEVARA [Énfasis: Jazz Y Músicas Populares: Bajo Eléctrico]

TRABAJO DE GRADO PUNK JAZZ LAURA PRADA LARA CARRERA DE ESTUDIOS MUSICALES BOGOTÁ, JUNIO DE 2019 ASESORES: SANIAGO BOTERO, LUIS GUEVARA [Énfasis: Jazz y Músicas Populares: Bajo Eléctrico] 1 CONTENIDO PROBLEMA DE INVESTIGACIÓN ....................................................................................................................2 OBJETIVO GENERAL.......................................................................................................................................3 OBJETIVOS ESPECÍFICOS ...............................................................................................................................3 JUSTIFICACIÓN ..............................................................................................................................................3 1. CAPITULO 1 ...........................................................................................................................................4 1.1 Los escenarios que gestaron el género: ¿Proto-Punk en Perú?....................................................4 1.2 Punk Norteamericano ..................................................................................................................7 1.3 La escena de Nueva York ..............................................................................................................8 1.4 La escena Inglesa.........................................................................................................................10 2. CAPITULO 2 - EL PUNK, UNA MIRADA ACTUAL A UN FENÓMENO SOCIAL.........................................15 -

Cassette Catalog - Pdf Edition

arvard Square Records, Inc. P.O. Box 381975, Cambridge, MA 02238 Year 2001 Rare And Out Of Print CASSETTE CATALOG - PDF EDITION •Order Toll Free:1-877-465-7669 (GOLPNOW) •Customer Service:(617) 868-3385 •Fax: (617) 547-2838 • Email: [email protected] For vinyl please contact us, or visit our website LPnow.com arvard Square Records, Inc. P.O. Box 381975, Cambridge, MA 02238 Year 2001 Rare And Out Of Print CASSETTE CATALOG - PDF EDITION •Order Toll Free:1-877-465-7669 (GOLPNOW) •Customer Service:(617) 868-3385 •Fax: (617) 547-2838 • Email: [email protected] For vinyl please contact us, or visit our website LPnow.com Special Note on Reserving Stock and Song Titles: Customer Info We do not reserve any stock nor do we have the song titles of any title available to us. Please do not call or email to see if something is in stock or Please read this before calling with questions. what songs are on any title. Everything in this catalog is available to us at press time, but we cannot guarantee the availability of any title on the HI! HI! phone. Placing an order is the best and fastest way to insure you get the Welcome to our year 2001 Sealed Cassette Catalog. titles you want. Orders begin only when payment or credit card # is received. We had no 1999/2000 Cassette catalog (sorry) so this is our 1st cassette The sooner you order, the sooner you will get your order. catalog since our 1998 one, which is now void. This catalog will be good We have many sources for most of the titles listed, but some titles have no until the end of 2001.