Amalthea Fund – September 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irish Economy Watch AIB Treasury Economic Research Unit

Irish Economy Watch AIB Treasury Economic Research Unit Thursday 19 November 2020 Mar-20 Apr-20 May-20 Jun-20 Jul-20 Aug-20 Sep-20 Oct-20 Manufacturing PMI edged higher to 50.3 in October as the MANUFACTURING survey points to broadly stable AIB Manufacturing PMI 45.1 36.0 39.2 51.0 57.3 52.3 50.0 50.3 but subdued business conditions in the sector OECD Leading Indicator 98.8 93.4 94.1 97.6 99.2 99.4 99.6 99.7 Traditional industrial production Industrial Production (Ex-Modern) 112.7 86.5 82.6 93.7 110.8 109.5 110.6 #N/A moved higher in September as Production (Ex-Modern) : 3mma YoY% 1.7 -10.0 -17.7 -21.2 -14.2 -5.3 -0.7 #N/A output rebounded by 25.9% in 3mth / 3mth % seas. adj. 2.4 -9.6 -16.3 -22.9 -6.6 11.4 25.9 #N/A Q3. YoY growth rate at –0.7% SERVICES / RETAIL Services PMI stayed in contraction but improved to 48.3 AIB Services PMI 32.5 13.9 23.4 39.7 51.9 52.4 45.8 48.3 in October. Weak demand was evident from a decline in new CSO Services Index (Value) 124.4 98.1 101.0 114.1 114.5 115.1 121.1 #N/A business, with firms linking this - YoY % -0.4 -21.8 -19.3 -10.5 -10.6 -9.1 -4.0 #N/A to Covid-19 restrictions - 3mth / 3mth % seas. -

You Can View the Full Spreadsheet Here

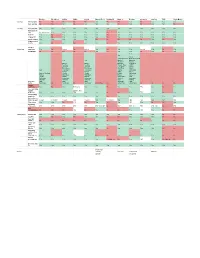

Barclays First Direct Halifax HSBC Lloyds Monzo (Free) Nationwide Natwest Revolut Santander Starling TSB Virgin Money Savings Savings pots No No No No No Yes No No Yes No Yes Yes Yes Auto savings No No Yes No Yes Yes Yes No Yes No Yes Yes No Banking Easy transfer yes Yes yes Yes yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes New payee in app Need debit card Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes New SO Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes change SO Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes pay in cheque Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No No No No No Yes No Yes share account details Yes No yes No yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Analyse Budgeting spending Yes No limited No limited Yes No Yes Yes Limited Yes No Yes Set Budget No No No No No Yes No Yes Yes No Yes No Yes Yes Yes Amex Allied Irish Bank Bank of Scotland Yes Yes Bank of Barclays Scotland Danske Bank of Bank of Barclays First Direct Scotland Scotland Danske Bank HSBC Barclays Barclays First Direct Halifax Barclaycard Barclaycard First Trust Lloyds Yes First Direct First Direct Halifax M&S Bank Halifax Halifax HSBC Monzo Bank of Scotland Lloyds Lloyds Lloyds Nationwide Halifax M&S Bank M&S Bank Monzo Natwest Lloyds MBNA MBNA Nationwide RBS Nationwide Nationwide Nationwide NatWest Santander NatWest NatWest NatWest RBS Starling Add other RBS RBS RBS Santander TSB banks Santander No Santander No Santander Not on free No Ulster Bank Ulster Bank No No No No Instant notifications Yes No Yes Rolling out Yes Yes No Yes Yes TBC Yes No Yes See upcoming regular Balance After payments -

Allied Irish Bank (GB) Comes Top Again in Comprehensive UK Banking Survey 27Th November 2000

Allied Irish Bank (GB) comes top again in comprehensive UK banking survey 27th November 2000 Allied Irish Bank (GB) has today been named Best Business Bank for the fourth consecutive time in the Forum of Private Business’s (FPB) comprehensive survey into the strength of service offered by banks to private businesses. The FPB report, Private Businesses and Their Banks 2000, is a biennial survey of tens of thousands of British businesses and shows that Allied Irish Bank (GB) has maintained its No. 1 position over other major UK banks since 1994. Aidan McKeon, General Manager of Allied Irish Bank (GB) and Managing Director AIB Group (UK) p.l.c., commented: "While we are delighted to win this award for the fourth time, we are far from complacent. We continue to listen closely to our customers and to invest in the cornerstones of our business: recruiting, training and retaining quality people; building 'true’ business relationships; and ongoing commitment to maintaining short lines of decision making. At the same time, we are exploiting technology to make our service as customer- responsive and efficient as possible." Allied Irish Bank (GB), one of the forerunners in relationship banking, scores highest in the survey for knowledge and understanding. The bank also scored highly on efficiency, reliability and customer satisfaction. Mr. McKeon continued: "We recognise that business customers have particular needs and concerns and we are always striving to ensure that our customers receive a continually improved service. We shall look carefully at this survey and liaise with our customers to further strengthen our service." Stan Mendham, Chief Executive of the FPB commented: "The FPB congratulates Allied Irish Bank (GB) on being voted Best Business Bank in Britain for the fourth time. -

Annual-Financial-Report-2009.Pdf

Contents 4 Chairman’s statement 255 Statement of Directors’ responsibilities in relation to the Accounts 6 Group Chief Executive’s review 256 Independent auditor’s report 8 Corporate Social Responsibility 258 Additional information 12 Financial Review 276 Principal addresses - Business description 278 Index - Financial data - 5 year financial summary - Management report - Capital management - Critical accounting policies - Deposits and short term borrowings - Financial investments available for sale - Financial investments held to maturity - Contractual obligations - Off balance sheet arrangements 59 Risk Management - Risk Factors - Framework - Individual risk types - Supervision and regulation 106 Corporate Governance - The Board & Group Executive Committee - Directors’ Report - Corporate Governance statement - Employees 119 Accounting policies 136 Consolidated income statement 137 Balance sheets 139 Statement of cash flows 141 Statement of recognised income and expense 142 Reconciliations of movements in shareholders’ equity 146 Notes to the accounts 1 Forward-Looking Information This document contains certain forward-looking statements within the meaning of the United States Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995 with respect to the financial condition, results of operations and business of the Group and certain of the plans and objectives of the Group. In particular, among other statements, certain statements in the Chairman’s statement, the Group Chief Executive’s review, and the Financial Review and Risk Management sections, with regard to management objectives, trends in results of operations, margins, risk management, competition and the impact of changes in International Financial Reporting Standards are forward-looking in nature.These forward-looking statements can be identified by the fact that they do not relate only to historical or current facts. -

The Ritz London, 16Th November 2016 by Invitation Only Confidential – Not for Distribution

® The Ritz London, 16th November 2016 By Invitation Only The AI Finance Summit is the world’s first and only high-level conference exploring the impact of Artificial Intelligence on the financial services industry. The invitation-only event, brings together CxOs from the world’s leading banks, insurance companies, asset management organisations, brokers. The event takes place at London’s most prestigious address, The Ritz, on the 16th of November and features world-class speakers presenting exclusive case studies shedding light into how the 4th industrial revolution will affect specifically affect the financial services industry. DRAFT AGENDA 16tH November 2016, The Ritz London 08:30 Registration, Breakfast refreshments & Networking 09:15 A welcome unlike any other… and Chair’s Opening Remarks 09:20 State of Play opening keynote: the 4th industrial revolution in financial services Where are financial services currently at with artificial intelligence, what technologies in particular are being used, how quickly is it being adopted, and what areas are leading the adoption of new intelligent technologies? These are are some of the pivotal questions answered in the scene-setting opening keynote to the AI Finance Summit. 09:45 Introducing a new era of risk management in investment banking The use of artificial intelligence within the world of investment banking is a phenomenon which is going to propel the industry in more ways than one. This talk will discuss how the advent of AI technologies, focusing on machine learning and cognitive computing, will drastically enhance risk management processes and achieve levels of accuracy previously unseen in the industry 10:10 Customer Experience/ Relations Management through AI platforms AI is revolutionizing customer service across every industry, with financial services already a pioneer in adoption. -

Information Memorandum ALLIED IRISH BANKS, P.L.C

Information Memorandum ALLIED IRISH BANKS, p.l.c. €5,000,000,000 Euro-Commercial Paper Programme Rated by Standard & Poor’s Credit Market Services Europe Limited and Fitch Ratings Ltd. Arranger UBS INVESTMENT BANK Issuing and Paying Agent CITIBANK Dealers AIB BARCLAYS BOFA MERRILL LYNCH CITIGROUP CREDIT SUISSE GOLDMAN SACHS INTERNATIONAL ING NOMURA THE ROYAL BANK OF SCOTLAND UBS INVESTMENT BANK The date of this Information Memorandum is 16 March 2016 Disclaimer clauses for Dealers, Issuing and Paying Agent and Arranger See the section entitled “Important Notice” on pages 1 to 4 of this Information Memorandum. IMPORTANT NOTICE This Information Memorandum (together with any supplementary information memorandum, and information incorporated herein by reference, the “Information Memorandum”) contains summary information provided by Allied Irish Banks, p.l.c. (the “Issuer” or “AIB”) in connection with a euro-commercial paper programme (the “Programme”) under which the Issuer acting through its office in Dublin or its London branch as set out at the end of this Information Memorandum may issue and have outstanding at any time euro-commercial paper notes (the “Notes”) up to a maximum aggregate amount of €5,000,000,000 or its equivalent in alternative currencies. Under the Programme, the Issuer may issue Notes outside the United States pursuant to Regulation S (“Regulation S”) under the United States Securities Act of 1933, as amended (the “Securities Act”). The Issuer has, pursuant to an amended and restated dealer agreement dated 16 March 2016 (the “Dealer Agreement”), appointed UBS Limited as arranger of the Programme (the “Arranger”), appointed Bank of America Merrill Lynch International Limited, Barclays Bank PLC, Citibank Europe plc, London Branch, Credit Suisse Securities (Europe) Limited, Goldman Sachs International, ING Bank N.V., Nomura International plc, The Royal Bank of Scotland plc and UBS Limited as dealers in respect of the Notes (together with Allied Irish Banks, p.l.c. -

AIB 2003 Cover 22/3/04 4:44 PM Page 1

AIB 2003 cover 22/3/04 4:44 PM Page 1 Allied Irish Banks, p.l.c. Annual Report and Accounts 2003 Report & Accounts 20032003 AIB Group Bankcentre PO BOX 452 Dublin 4 Ireland Tel. +353 (0) 1 660 0311 www.aibgroup.com This is the new-style report and accounts document from AIB. The Chairman’s statement is on pages 8/9 and the Group Chief Executive’s review starts on page 12. It includes for the first time statements on Corporate and Social Responsibility, on page 16, and AIB and its people, on page 17. For the latest information, please visit our websites listed opposite. 3 4 Contents 7 Financial highlights 8 Chairman’s statement 10 AIB Board/Executive Committee 12 Group Chief Executive’s review 15 AIB at a glance 16 Corporate and Social Responsibility 17 AIB and its people 19 Performance review 37 Financial review 48 Report of the Directors 50 Corporate Governance 54 Accounting policies 59 Consolidated profit and loss account 61 Consolidated balance sheet 62 Balance sheet Allied Irish Banks, p.l.c. 63 Consolidated cash flow statement 64 Reconciliation of movements in shareholders’ funds 64 Note of historical cost profits and losses 65 Notes to the accounts 140 Statement of Directors’ responsibilities in relation to the Accounts 141 Independent auditors’ report 143 Additional financial information 145 Accounts in sterling, US dollars and Polish zloty 146 Five year financial summary 148 Principal addresses 150 Additional information for shareholders 154 Financial calendar 155 Index 5 Forward-Looking Information. This document contains certain forward- looking statements within the meaning of the United States Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995 with respect to the financial condition, results of operations and business of the Group and certain of the plans and objectives of the Group. -

UK Banks Using Confirmation

UK banks using Confirmation UK Finance has partnered with Confirmation, part of Thomson Reuters to deliver UK Finance confirmations to UK banks, enabling them to access the Confirmation network. Confirmation is a secure online platform that helps banks respond to more confirmation requests from auditors all over the world, in less time - centralising it all in one place. Find out more about Confirmation: www.confirmation.com The following UK based Financial Institutions are responding to audit requests through Confirmation: Adam & Co KBC Bank NV London Branch Ahli United Bank (UK) PLC Kookmin Bank London Branch* Allfunds Bank S.A.U. (London Branch) Lloyds Bank Corporate Markets (LBCM) Allied Irish Bank (GB) (UK) Lloyds Bank PLC ANZ UK* Lloyds Bank International Banco Santander Syndicated Loans UK Macquarie Bank - Commodities and Global Markets* Bank of America Merrill Lynch* Maybank (Malaysian Banking Berhad) Bank of China (UK) Limited Metro Bank PLC Bank of Scotland Mizuho Bank (UK) Bank Leumi (UK) Morgan Stanley BBVA CIB (Corporate & Investment Banking) MUFG UK London Branch* BBVA BEC (Corporate Banking) London Branch* MUFG Funding (UK) Ltd., London Branch BBVA Commercial Banking Vauxhall Branch MUFG Securities EMEA PLC BMO Capital Markets National Australia Bank - UK (London Branch) BNI (PT Bank Negara Indonesia) Nationwide Building Society BNP Paribas UK NatWest BNY Mellon NatWest International Centtrip* Nordea Bank Charter Court Financial Services (UK) Piraeus Bank CIMB Banking Rabobank London Citibank– Accounts Domiciled in Europe* Reliance Bank (UK) Coutts & Co Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) Credit Industriel et Commercial (CIC) Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) International Credit Agricole Santander (UK)* Company number: 10250295. -

List of Correspondent Banks Europe

LIST OF CORRESPONDENT BANKS EUROPE UNITED KINGDOM 1 Allied Irish Bank, London AIBK GB 2L 2 Arab National Bank, London ARNB GB 2L 3 Australia & New Zealand Banking Group Ltd. London ANZB GB 2L 4 Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria SA, London BBVA GB 2L 5 Bank of America NA, London BOFA GB 22 6 Bank of Ireland Foreign and Branch Services, London BOFI GB 22 7 Bank of Tokyo Mitsubishi UFJ, Ltd., London BOTK GB 2L 8 Bank Sepah International Plc, London SEPB GB 2L 9 Barclays Bank Plc (All UK Offices) BARC GB 22 10 BNP Paribas, London BNPA GB 22 11 Citibank NA, London CITI GB 2L 12 Clydesdale Bank Plc, Glasgow CLYD GB 2S / YORK GB 22 13 Commerzbank AG, London COBA GB 2X 14 Co-operative Bank Plc, London CPBK GB 22 15 Danske Bank DABA GB 2L 16 DB UK Bank Ltd., London MGCO GB 2L 17 Deutsche Bank, London DEUT GB 2L 18 Europe Arab Bank Plc, London ARAB GB 2L 19 Fortis Bank SA, London GEBA GB 22 20 Gulf International Bank, London GULF GB 2L 21 Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Limited, London HSBC GB 2L 22 HSBC Asset Management (Europe) Ltd., London HSBC GB 22 23 HSBC Bank Plc, London MIDL GB 22 24 HSBC Private Bank Ltd., London SMCO GB 2P 25 ING Bank NV, London INGB GB 2L 26 JPMorgan Chase Bank NA, London CHAS GB 2L 27 KBC Bank NV, London KRED GB 2X 28 Korea Exchange Bank, London KOEX GB 2L 29 Lloyds TSB Bank Plc, London LOYD GB 22 / LOYD GB 2L 30 Merrill Lynch International Bank Limited MLIB GB 3X 31 Mizrahi Tefahot Bank Ltd., London MIZB GB 2L 32 Mizuho Corporate Bank, Ltd., London MHCB GB 2L 33 National Westminster Bank Plc, London NWBK GB -

Irish Economy Watch AIB Treasury Economic Research Unit

Irish Economy Watch AIB Treasury Economic Research Unit Friday 26 March 2021 Jul-20 Aug-20 Sep-20 Oct-20 Nov-20 Dec-20 Jan-21 Feb-21 Manufacturing PMI was little changed at 52.0 in February. MANUFACTURING However, output and new AIB Manufacturing PMI 57.3 52.3 50.0 50.3 52.2 57.2 51.8 52.0 orders contracted again as underlying business conditions OECD Leading Indicator 99.0 99.3 99.7 100.1 100.3 100.6 100.7 100.8 remain weak in the sector Industrial Production (Ex-Modern) 110.5 108.6 108.6 110.8 109.2 114.5 116.2 #N/A Traditional industrial production Production (Ex-Modern) : 3mma YoY% -14.2 -5.4 -1.3 -1.6 -2.7 -0.1 -0.2 #N/A continued to rise in January, but 3mth / 3mth % seas. adj. -6.8 11.4 24.8 14.5 5.1 2.1 3.6 #N/A 3mma down 0.2% YoY In February the services PMI SERVICES / RETAIL remained in contraction at 41.2. AIB Services PMI 51.9 52.4 45.8 48.3 45.4 50.1 36.2 41.2 The continuation of restrictions resulted in a further decline in CSO Services Index (Value) 113.9 114.8 120.5 115.4 112.3 120.5 113.6 #N/A new business. On a more - YoY % -10.9 -9.0 -4.2 -7.4 -10.2 -1.3 -9.0 #N/A optimistic note, firms future outlook rose sharply to its - 3mth / 3mth % seas. -

UK & EU Unsupported Banks

UK & EU Unsupported Bank List EU Unsupported Banks (Bank and Credit Cards only) UK Unsupported Banks (Bank and Credit Cards only) ABANCA (Business) (Spain) - Bank AA credit card (UK) ABANCA (Spain) - Bank AA Savings (UK) - Bank ABN AMRO (Netherlands) - Bank Abbey National (UK) - Credit Card ABN Amro Business Credit Card (Netherlands) Adam & Company (UK) - Bank Activo Bank (Portugal) Airdrie Savings Bank (UK) ActivoBank (Espana) - Banco Aldermore Business Bank (UK) Allied Irish Bank (Business) (Ireland) - Bank Aldermore Savings (UK) - Bank Allied Irish Bank (Business) (Ireland) - Credit Card Alliance & Leicester (UK) - Bank Allied Irish Bank (Ireland) - Bank Alliance & Leicester (UK) - Credit Card Allied Irish Bank (Ireland) - Credit Card Alliance Trust Savings (UK) - Bank American Express (Card Account) (Espana) - Tarjeta de Allied Irish Business Bank (UK) - Bank Credito American Express Card Amazon Credit Card (UK) American Express Cards (France) - Bank American Express Business Cards (UK) American Express Cards (Switzerland) American Express Cards (global) (UK) - Credit Card American Express Cards (Switzerland) American Express Cards (UK) American Express Cards DUTCH (Netherlands) - Bank American Express Cards Mobile (UK) - Credit Card American Express cards(NL) (Netherlands) - Credit Card aqua card (UK) American Express Credit Cards (Spain) Arbuthnot Latham (Current Account) (UK) - Bank ASN Bank (Netherlands) - Bank Arbuthnot Lathum (UK) - Bank ASN Bank (Netherlands) - Credit Card ASDA - Credit Cards (UK) AXA Banque (France) Bank of -

List of Banking Brands – June 2021

LIST OF BANKING AND SAVINGS BRANDS PROTECTED BY THE SAME FSCS COVERAGE COMPILED BY THE BANK OF ENGLAND AS AT 11 JUNE 2021 Please note this list is not updated on a continuous basis. It is also possible that separate firms (with different Firm Reference Numbers) are part of a group of companies that use similar brand names (i.e, a simplified common version of the firms’ legal names). If you have multiple deposits across a group of firms using similar brand names, you should check with the firms whether the £85k deposit protection limit is shared. Banking and Savings Brand PRA-authorised institution FRN Other deposit brands covered by FSCS coverage 114724 The Royal Bank of Scotland Plc 114724 RBS 114724 Adam & Company Adam & Company The Royal Bank of Scotland Plc 114724 Drummonds 114724 Child & Co 114724 Holt's 114724 The One account/Virgin One account/Nat West One account 671140 Advanced Payment Solutions Limited Advanced Payment Solutions Limited Advanced Payment Solutions Limited 671140 Cashplus 671140 Cashplus Bank 122088 AIB (NI) 122088 Allied Irish Bank (GB) AIB Group (UK) Plc AIB Group (UK) Plc 122088 Allied Irish Bank (GB) Savings Direct 122088 First Trust Bank 143336 Arbuthnot Latham & Co Limited Arbuthnot Latham & Co Limited Arbuthnot Latham & Co Limited 143336 Arbuthnot Direct 121873 Clydesdale Bank Plc 121873 B B Clydesdale Bank Plc 121873 Virgin Money 121873 Yorkshire Bank 136261 Banco Santander S.A. Banco Santander S.A. Banco Santander S.A. 136261 Santander Corporate & Investment Banking 204459 Bank and Clients PLC Bank and