Privatization in Italy 1993-2002: Goals, Institutions, Outcomes, and Outstanding Issues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enel Green Power, Sharp and Stmicroelectronics Sign Agreement for the Largest Photovoltaic-Panel Manufacturing Plant in Italy

Enel Green Power, Sharp and STMicroelectronics Sign Agreement for the Largest Photovoltaic-Panel Manufacturing Plant in Italy January 4, 2010 3:04 AM ET Enel Green Power, Sharp and STMicroelectronics join forces to produce innovative thin-film photovoltaic panels. The plant, located in Catania, Italy, is expected to have initial production capacity of 160 MW per year and is targeted to grow to 480 MW over the next years. In addition, Enel Green Power and Sharp will jointly develop solar farms focusing on the Mediterranean area, with a total installed capacity at a level of 500 MW, by the end of 2016. Geneva, January 4, 2010 – Today, Enel Green Power, Sharp and STMicroelectronics signed an agreement for the manufacture of triple-junction thin-film photovoltaic panels in Italy. At the same time, Enel Green Power and Sharp signed a further agreement to jointly develop solar farms. Today's agreement regarding the photovoltaic panel factory follows the Memorandum of Understanding signed in May 2008 by Enel Green Power and Sharp. STMicroelectronics has joined this strategic partnership. This agreement marks the first time that three global technology and industrial powerhouses have joined together in an equal partnership to contribute their unique value-add to the solar industry. It brings together Enel Green Power, with its international market development and project management know-how; Sharp, and its exclusive triple-junction thin-film technology, which will be operational in the mother plant in Sakai, Japan as of spring 2010; and STMicroelectronics, with its manufacturing capacity, skills and resources in highly advanced, hi-tech sectors such as microelectronics. -

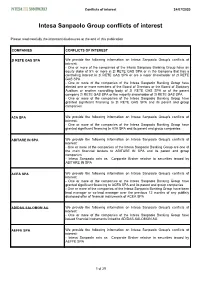

Intesa Sanpaolo Group Conflicts of Interest

Conflicts of interest 24/07/2020 Intesa Sanpaolo Group conflicts of interest Please read carefully the important disclosures at the end of this publication COMPANIES CONFLICTS OF INTEREST 2I RETE GAS SPA We provide the following information on Intesa Sanpaolo Group's conflicts of interest: - One or more of the companies of the Intesa Sanpaolo Banking Group have an equity stake of 5% or more in 2I RETE GAS SPA or in the Company that has a controlling interest in 2I RETE GAS SPA or are a major shareholder of 2I RETE GAS SPA - One or more of the companies of the Intesa Sanpaolo Banking Group have elected one or more members of the Board of Directors or the Board of Statutory Auditors or another controlling body of 2I RETE GAS SPA or of the parent company 2I RETE GAS SPA or the majority shareholder of 2I RETE GAS SPA - One or more of the companies of the Intesa Sanpaolo Banking Group have granted significant financing to 2I RETE GAS SPA and its parent and group companies A2A SPA We provide the following information on Intesa Sanpaolo Group's conflicts of interest: - One or more of the companies of the Intesa Sanpaolo Banking Group have granted significant financing to A2A SPA and its parent and group companies ABITARE IN SPA We provide the following information on Intesa Sanpaolo Group's conflicts of interest: - One or more of the companies of the Intesa Sanpaolo Banking Group are one of the main financial lenders to ABITARE IN SPA and its parent and group companies - Intesa Sanpaolo acts as Corporate Broker relative to securities issued -

TEA6422 TEA6422D TEA6422DT Stmicroelectronics Datasheet

TEA6422 BUS-CONTROLLED AUDIO MATRIX ■ 6 Stereo Inputs ■ 3 Stereo Ouputs ■ Gain Control 0 dB/Mute for each Output ■ Cascadable (2 different addresses) ■ Serial Bus Controlled ■ Very Low Noise ■ Very Low Distorsion SHRINK DIP24 ■ Fully ESD Protected (Shrink Plastic Package) ■ Wide Audio Dynamic Range ( 3 V ) RMS ORDER CODE: TEA6422 DESCRIPTION The TEA6422 switches 6 stereo audio inputs on 3 stereo outputs. All the switching possibilities are changed through the I2C BUS. SO28 (Plastic Monopackage) ORDER CODE: TEA6422D Figure 1. PIN CONNECTIONS SO28 SDIP24 GND 1 28 SDA GND 1 24 SDA CAPACITANCE 2 27 SCL 2 23 CAPACITANCE SCL VS 3 26 ADDR VS 3 22 ADDR L1 4 25 R1 L1 4 21 R1 L2 5 24 R2 L2 5 20 R2 L3 6 23 R3 L3 6 19 R3 NC 7 22 NC L4 7 18 R4 NC 8 21 NC L5 8 17 R5 L4 9 20 R4 L6 9 16 R6 L5 10 19 R5 LOUT1 10 15 ROUT3 L6 11 18 R6 ROUT1 11 14 LOUT3 LOUT1 12 17 ROUT3 LOUT2 12 13 ROUT2 ROUT1 13 16 LOUT3 LOUT2 14 15 ROUT2 September 2003 1/10 1 TEA6422 BLOCK DIAGRAM RIGHT INPUTS GAIN = 0 dB RIGHT OUTPUTS VS SDA C SUPPLY BUS DECODER SCL GND ADDR LEFT OUTPUTS GAIN = 0 dB LEFT INPUTS ABSOLUTE MAXIMUM RATINGS Symbol Parameter Value Unit VCC Supply Voltage 12 V o Toper Operating Temperature 0, + 70 C o Tstg Storage Temperature - 20, + 150 C THERMAL DATA Symbol Parameter Value Unit SDIP24 75 oC/W R (j-a) Junction - ambient Thermal Resistance th SO28 75 oC/W 2/10 1 TEA6422 ELECTRICAL CHARACTERISTICS o Ω Ω TA = 25 C, VS = 9 V, RL = 10 k , RG = 600 , f = 1 kHz (unless otherwise specified) Symbol Parameter Test Conditions Min. -

4133-6266-6020.6 EMTN PROGRAMME PROSPECTUS This

EMTN PROGRAMME PROSPECTUS This document constitutes two base prospectuses: (i) the base prospectus of TIM S.p.A. and (ii) the base prospectus of Telecom Italia Finance S.A. (together, the EMTN Programme Prospectus). TIM S.p.A. (incorporated with limited liability under the laws of the Republic of Italy) TELECOM ITALIA FINANCE S.A. (incorporated with limited liability under the laws of the Grand-Duchy of Luxembourg) €20,000,000,000 Euro Medium Term Note Programme unconditionally and irrevocably guaranteed in respect of Notes issued by Telecom Italia Finance S.A. by TIM S.p.A. (incorporated with limited liability under the laws of the Republic of Italy) Under this €20,000,000,000 Euro Medium Term Note Programme (the Programme), TIM S.p.A. (TIM) and Telecom Italia Finance S.A. (TI Finance and, together with TIM in its capacity as an issuer, the Issuers and each an Issuer) may from time to time issue notes (the Notes) denominated in any currency agreed with the relevant Dealer (as defined below). Payment of all amounts owing in respect of the Notes issued by TI Finance will be unconditionally and irrevocably guaranteed by TIM (in such capacity, the Guarantor). The maximum aggregate nominal amount of all Notes from time to time outstanding under the Programme will not exceed €20,000,000,000 (or its equivalent in other currencies calculated as described in the Programme Agreement), subject to increase as described herein. The Notes may be issued on a continuing basis to one or more of the Dealers specified under “Overview of the Programme” and any additional Dealer appointed under the Programme from time to time by the Issuers (each a Dealer and, together, the Dealers), which appointment may be for a specific issue or on an ongoing basis. -

World's Smallest Micro-Mirror Scanning Technology From

Press release Communiqué de presse Comunicato stampa 新闻稿 / 新聞稿 プレスリリース 보도자료 T4264D World’s Smallest Micro-Mirror Scanning Technology from STMicroelectronics Chosen for Intel® RealSense™ High-Resolution LiDAR Depth Camera L515 Power-efficient, hi-res LiDAR camera capturing millions of depth points per second suits a wide range of Industrial and Computing use cases Geneva, March 8, 2021 – STMicroelectronics (NYSE: STM), a global semiconductor leader serving customers across the spectrum of electronics applications, has developed a tiny MEMS mirror with Intel enabling spatial scanning of an environment. Intel developed a LiDAR system based on this micro-mirror, providing high-resolution scanning for industrial applications such as robotic arms for bin picking, volumetric measurements, logistics, and 3D scanning. Built into the Intel RealSense LiDAR1 Camera L515, the small dimensions of the ST micro-mirror contribute to the LiDAR camera’s hockey-puck size (61mm diameter x 26mm height). The micro-mirror enables continuous laser scanning across the entire field of view. In combination with a custom photodiode sensor, the RealSense LiDAR Camera L515 renders a 3D depth map of the entire scene. “With 30 frames per second and a field-of-view of 70° by 55°, ST’s 2nd-generation micro-mirror continues to set the bar for 3D scanning and detection applications,” said Benedetto Vigna, President Analog, MEMS and Sensors Group, STMicroelectronics. “Continuing the long-term supply relationship for micro-mirrors with Intel demonstrates our never-ending efforts to leverage our long-lasting leadership in MEMS to meet the demanding technical and supply needs of our customers.” The L515 leverages the scanning capabilities of ST’s MEMS to deliver high-resolution depth with no interpolated pixels, the ability to control the field of view, and provides close to zero pixel blur driven by the low 50nS exposure time. -

E N a C / Eetac Atr

E N A C / EETAC ATR FAA regulation analysis for ATR ETOPS validation Jordi CLARAMUNT SEGURA IENAC14 - Erasmus End of studies report / Treball Final de Grau 11/08/2017 FAA regulation analysis for ATR ETOPS validation 2 3 FAA regulation analysis for ATR ETOPS validation Acknowledgements With deepest gratitude and appreciation, I humbly give thanks to the people who helped me in making this end of studies project a possible one. First of all, I would like to offer my special thanks to Souhir Charfeddine, my internship tutor in ATR, for choosing me among the other candidates and giving me the possibility to perform this internship. Thanks for her valuable and constructive help during the planning and development of this internship. I really appreciate all the time she has dedicated to me with all the different meetings we have had inside the company. I have learnt a lot at her side, she has been an amazing tutor. Thank you. I am also grateful to all of those with whom I have had the pleasure to work with during this project. Each of the members I have worked with have provided me extensive and professional guidance and taught me a great deal about certification aspects, as well as other domains. Those include Antonio Paradies, Didier Cailhol, Eric Bédessem, Ciro Manco, Fabien Vançon, Jean-Paul Delpont, Nadège Gualina and Lucille Mitchell. Also, I would like to offer my gratitude to ENAC for first, giving me the possibility to join their Erasmus programme in its great university and then, for allowing me having the chance to do the internship, which has been the best election of my life so far. -

John Hancock Disciplined Value International Fund A: JDIBX C: JDICX I: JDVIX R2: JDISX R4: JDITX R6: JDIUX

All data is as of June 30, 2021 Q2 - 2021 International equity fund Quarterly commentary John Hancock Disciplined Value International Fund A: JDIBX C: JDICX I: JDVIX R2: JDISX R4: JDITX R6: JDIUX Objective Use for Morningstar category Long-term growth of capital Core international holding Foreign Large Value Quarterly commentary Highlights The fund beneited from strong stock selection in the communication International equities rallied in the second quarter, helping the fund’s services sector, where SK Telecom Co., Ltd. was a top performer ater its benchmark—the MSCI EAFE Index—achieve a series of all-time highs management announced a plan to split the company in two to recognize before it peaked in mid-June. value. The fund also outperformed in energy, due largely to a rally in shares The fund delivered a positive return, but it trailed the index. of Cenovus Energy, Inc., IMI PLC, and Hitachi Corp. All three companies Given the underperformance of the value style relative to growth, the were top contributors for the quarter, as was a zero weighting in the fund’s value-driven strategy was a headwind to results compared with the Japanese company Sotbank Group Corp. broad-based benchmark. Market review and outlook Portfolio changes International stocks performed well in the past three months as economic We increased the fund’s weightings in industrials and healthcare while data continued to improve as the gradual rollout of vaccines fostered a reducing its allocation to information technology. The changes were all resumption of normal business conditions. Broad measures of consumer stock speciic, and the structure of the portfolio didn’t change materially. -

Euro Stoxx® Residual Momentum Premium Index

EURO STOXX® RESIDUAL MOMENTUM PREMIUM INDEX Components1 Company Supersector Country Weight (%) EUROFINS SCIENTIFIC null null 3.37 SARTORIUS STEDIM BIOTECH null null 3.20 EDP RENOVAVEIS null null 2.97 HELLOFRESH AG null null 2.21 SIEMENS GAMESA null null 2.21 SARTORIUS PREF. null null 2.16 KESKO null null 2.07 DEUTSCHE POST null null 1.89 CORBION null null 1.81 BRENNTAG null null 1.80 SIGNIFY null null 1.75 ZALANDO null null 1.68 SEB null null 1.56 LVMH MOET HENNESSY null null 1.52 BOLLORE null null 1.48 INTERPUMP GRP null null 1.45 SIEMENS null null 1.44 CAP GEMINI null null 1.41 RATIONAL null null 1.41 BMW null null 1.40 BANCO BPM null null 1.37 FUCHS PETROLUB PREF null null 1.30 SOITEC null null 1.27 SAINT GOBAIN null null 1.25 PUBLICIS GRP null null 1.23 MICHELIN null null 1.22 UNIBAIL-RODAMCO-WESTFIELD null null 1.20 WARTSILA null null 1.15 CAIXABANK null null 1.13 STELLANTIS null null 1.12 CNH Industrial NV null null 1.12 SOLVAY null null 1.11 BCO BILBAO VIZCAYA ARGENTARIA null null 1.09 PROSIEBENSAT.1 MEDIA null null 1.08 NOKIAN RENKAAT null null 1.08 COVESTRO null null 1.06 DEUTSCHE BANK null null 1.02 INFINEON TECHNOLOGIES null null 1.02 DAIMLER null null 1.02 STMICROELECTRONICS null null 1.02 CONTINENTAL null null 1.01 REXEL null null 0.99 FLUTTER ENTERTAINMENT null null 0.99 AALBERTS null null 0.99 COMMERZBANK null null 0.95 RYANAIR null null 0.94 HEIDELBERGCEMENT null null 0.93 BASF null null 0.93 ASML HLDG null null 0.93 SPIE null null 0.90 ING GRP null null 0.90 ELIS null null 0.89 HERMES INTERNATIONAL null null 0.88 ASM -

Semiconductors & Semiconductor Equipment

Semiconductors & Semiconductor Equipment Driving forces Highlighted criteria & The application of advanced semiconductors has progressed dimension weights beyond traditional computing products to include the Internet Environmental Dimension..34% of Things, Artificial Intelligence, automotive applications, 5G, – Climate Strategy and high-performance computing. Cybersecurity is a strategic – Environmental Policy & priority that is increasing in importance, since security should Management Systems be included by design during chip R&D. The rate at which the – Operational Eco-Efficiency number of transistors on a chip doubles (i.e., Moore’s Law) is – Product Stewardship slowing as integrated circuits become smaller. The semiconductor industry must, therefore, investigate new architectures, materials, Social Dimension ............. 23% and packaging to go beyond current scaling and performance – Human Capital Development constraints, while also addressing the demand for low energy- – Talent Attraction & Retention consumption products. To sustain a rapid pace of innovation, the industry will need to increase R&D investment that, in turn, Governance & Economic will necessitate attracting and retaining a skilled workforce and Dimension ........................ 43% developing talent. The industry must continue to improve its – Innovation Management ultra-pure water usage, energy and waste management, and – Product Quality and Recall pollution prevention. It must also increase promotion of projects Management to substitute hazardous materials and -

Yield Crescendo Tempo Autocall Step Down on Intesa Sanpaolo

Key Information Document This document provides you with key information about this investment product. It is not marketing material. The information is required by law to help you understand the nature, risks, costs, potential gains and losses of this product and to help you compare it with other products. YIELD CRESCENDO TEMPO AUTOCALL STEP DOWN ON INTESA SANPAOLO, UNICREDIT AND STMICROELECTRONICS - EUR - JANUARY 2022 ISIN: FREXA0014771 Issuer: Exane Finance | Guarantor: Exane Derivatives | Supervisor: Autorité des Marchés Financiers and Autorité de Contrôle Prudentiel et de Résolution | Telephone Number: (+33) 1 44 95 70 00 | Website: www.exane.com KID production date: 4/07/2019 You are about to purchase a product that is not simple and may be difficult to understand. WHAT IS THIS PRODUCT? TYPE: Certificate indexed to one or more Underlyings. OBJECTIVES The Certificate Yield Crescendo Tempo Autocall Step Down on Intesa Sanpaolo, Unicredit and STMicroelectronics - EUR - January 2022 issued by Exane Finance carries a risk of capital loss during its life and at maturity. Coupon mechanism On each Interest Payment Date, if the official closing price of each Underlying on the Coupon Valuation Date is higher than or equal to 50% of its Initial Price, the Holder will receive a coupon of EUR 10 and in addition to the current coupon, all previously missed coupons. Otherwise, no coupon is paid for the period. Automatic Early settlement On each Automatic Early Settlement Date, if the official closing price of each Underlying on the Automatic Early Valuation Date is higher than or equal to the decreasing redemption barrier (as a percentage of its Initial Price), the product is early redeemed and the Holder will receive an amount corresponding to EUR 1,000. -

Fascist Italy's Aerial Defenses in the Second World War

Fascist Italy's Aerial Defenses in the Second World War CLAUDIA BALDOLI ABSTRACT This article focuses on Fascist Italy's active air defenses during the Second World War. It analyzes a number of crucial factors: mass production of anti- aircraft weapons and fighters; detection of enemy aircraft by deploying radar; coordination between the Air Ministry and the other ministries involved, as well as between the Air Force and the other armed services. The relationship between the government and industrialists, as well as that between the regime and its German ally, are also crucial elements of the story. The article argues that the history of Italian air defenses reflected many of the failures of the Fascist regime itself. Mussolini's strategy forced Italy to assume military responsibilities and economic commitments which it could not hope to meet. Moreover, industrial self-interest and inter-service rivalry combined to inhibit even more the efforts of the regime to protect its population, maintain adequate armaments output, and compete in technical terms with the Allies. KEYWORDS air defenses; Air Ministry; anti-aircraft weapons; bombing; Fascist Italy; Germany; radar; Second World War ____________________________ Introduction The political and ideological role of Italian air power worked as a metaphor for the regime as a whole, as recent historiography has shown. The champions of aviation, including fighter pilots who pursued and shot down enemy planes, represented the anthropological revolution at the heart of the totalitarian experiment.1 As the Fascist regime had practiced terrorist bombing on the civilian populations of Ethiopian and Spanish towns and villages before the Second World War, the Italian political and military leadership, press, and industrialists were all aware of the potential role of air 1. -

Italy's Largest Photovoltaic Panel Plant Starts

ITALY’S LARGEST PHOTOVOLTAIC PANEL PLANT STARTS COMMERCIAL PRODUCTION The new industrial plant run by 3SUN – a joint venture equally owned by Enel Green Power, Sharp and STMicroelectronics – has begun commercial manufacturing operations. In its initial phase it will manufacture photovoltaic modules for a potential output of 160MW per year. The Catania plant will supply the most promising markets of Europe, the Middle East and Africa Rome, December 23rd, 2011 – Today marks the first day of commercial manufacturing operations in Catania’s new plant dedicated to technologically innovative solar panels, run by 3Sun, a joint venture company owned by Enel Green Power, Sharp and STMicroelectronics. This is the biggest solar panel plant in Italy, and one of the biggest in Europe. The construction of the plant was financed by a mix of capital from the partners, CIPE’s funding and project financing with three major lending institutions, namely Banca IMI, Centrobanca and Unicredit. In this first phase the plant will produce multi-junction thin- film photovoltaic panels for a capacity of 160MW per year, and will employ around 280 people. The factory’s output is intended to meet the demand of solar power markets in Europe, the Middle East and Africa (EMEA), using both projects under development and the sales networks of Enel Green Power and Sharp. For this purpose, Enel Green Power and Sharp have set up a second joint venture, ESSE (Enel Green Power & Sharp Solar Energy), to develop, build and operate photovoltaic systems in the EMEA area with an output target of over 500MW by 2016, using panels manufactured by the factory.