A REVIEW Levi, Herbert W . 1982

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE SPIDER FAMILIES of EUROPE: Keys, Diagnoses and Diversity DIE

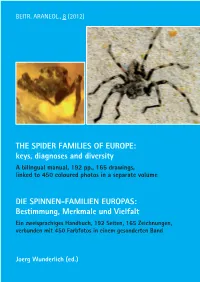

BEITR. ARANEOL., 8 (2012) THE SPIDER FAMILIES OF EUROPE: keys, diagnoses and diversity A bilingual manual, 192 pp., 165 drawings, linked to 450 coloured photos in a separate volume DIE SPINNEN-FAMILIEN EUROPAS: Bestimmung, Merkmale und Vielfalt Ein zweisprachiges Handbuch, 192 Seiten, 165 Zeichnungen, verbunden mit 450 Farbfotos in einem gesonderten Band Joerg Wunderlich (ed.) BEITR. ARANEOL., 8 (2012) Photos on the front cover / Fotos auf dem Buchdeckel: On the left: Frontal aspect of a Jumping Spider (Salticidae) in Eocene Baltic amber. Note the huge anterior median eyes. Links: Eine Springspinne in Baltischem Bernstein, Vorderansicht. Man beachte die sehr großen, scheinwerferartig nach vorn gerichteten vorderen Mittelaugen. On the right: A male sparassid spider of Eusparassus dufouri SIMON on sand, Portugal. Note the laterigrade leg position of this very large spider, which legs spun seven cms. Rechts: Männliche Riesenkrabbenspinne (Sparassidae) (Eusparassus dufouri) auf Sand, Portugal. Man beachte die zur Seite gerichteten Beine dieser sehr großen Spinne mit einer Spannweite der Vorderbeine von sieben Zentimetern. 1 2 BEITR. ARANEOL., 8 (2012) THE SPIDER FAMILIES OF EUROPE: keys, diagnoses and diversity A bilingual manual, 192 pp., 165 drawings, linked to 450 coloured photos in a separate volume DIE SPINNEN-FAMILIEN EUROPAS: Bestimmung, Merkmale und Vielfalt Ein zweisprachiges Handbuch, 192 Seiten, 165 Zeichnungen, verbunden mit 450 Farbfotos in einem gesonderten Band Editor and author: JOERG WUNDERLICH © Publishing House: Joerg Wunderlich, 69493 Hirschberg, Germany Print: M + M Druck GmbH, Heidelberg. Orders for this and other volume(s) of the Beitr. Araneol. (see p. 192): Publishing House Joerg Wunderlich Oberer Haeuselbergweg 24 69493 Hirschberg Germany E-mail: [email protected] ISBN 978-3-931473-14-2 3 BEITR. -

Comparative Functional Morphology of Attachment Devices in Arachnida

Comparative functional morphology of attachment devices in Arachnida Vergleichende Funktionsmorphologie der Haftstrukturen bei Spinnentieren (Arthropoda: Arachnida) DISSERTATION zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades doctor rerum naturalium (Dr. rer. nat.) an der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel vorgelegt von Jonas Otto Wolff geboren am 20. September 1986 in Bergen auf Rügen Kiel, den 2. Juni 2015 Erster Gutachter: Prof. Stanislav N. Gorb _ Zweiter Gutachter: Dr. Dirk Brandis _ Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 17. Juli 2015 _ Zum Druck genehmigt: 17. Juli 2015 _ gez. Prof. Dr. Wolfgang J. Duschl, Dekan Acknowledgements I owe Prof. Stanislav Gorb a great debt of gratitude. He taught me all skills to get a researcher and gave me all freedom to follow my ideas. I am very thankful for the opportunity to work in an active, fruitful and friendly research environment, with an interdisciplinary team and excellent laboratory equipment. I like to express my gratitude to Esther Appel, Joachim Oesert and Dr. Jan Michels for their kind and enthusiastic support on microscopy techniques. I thank Dr. Thomas Kleinteich and Dr. Jana Willkommen for their guidance on the µCt. For the fruitful discussions and numerous information on physical questions I like to thank Dr. Lars Heepe. I thank Dr. Clemens Schaber for his collaboration and great ideas on how to measure the adhesive forces of the tiny glue droplets of harvestmen. I thank Angela Veenendaal and Bettina Sattler for their kind help on administration issues. Especially I thank my students Ingo Grawe, Fabienne Frost, Marina Wirth and André Karstedt for their commitment and input of ideas. -

Insects & Spiders of Kanha Tiger Reserve

Some Insects & Spiders of Kanha Tiger Reserve Some by Aniruddha Dhamorikar Insects & Spiders of Kanha Tiger Reserve Aniruddha Dhamorikar 1 2 Study of some Insect orders (Insecta) and Spiders (Arachnida: Araneae) of Kanha Tiger Reserve by The Corbett Foundation Project investigator Aniruddha Dhamorikar Expert advisors Kedar Gore Dr Amol Patwardhan Dr Ashish Tiple Declaration This report is submitted in the fulfillment of the project initiated by The Corbett Foundation under the permission received from the PCCF (Wildlife), Madhya Pradesh, Bhopal, communication code क्रम 車क/ तकनीकी-I / 386 dated January 20, 2014. Kanha Office Admin office Village Baherakhar, P.O. Nikkum 81-88, Atlanta, 8th Floor, 209, Dist Balaghat, Nariman Point, Mumbai, Madhya Pradesh 481116 Maharashtra 400021 Tel.: +91 7636290300 Tel.: +91 22 614666400 [email protected] www.corbettfoundation.org 3 Some Insects and Spiders of Kanha Tiger Reserve by Aniruddha Dhamorikar © The Corbett Foundation. 2015. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used, reproduced, or transmitted in any form (electronic and in print) for commercial purposes. This book is meant for educational purposes only, and can be reproduced or transmitted electronically or in print with due credit to the author and the publisher. All images are © Aniruddha Dhamorikar unless otherwise mentioned. Image credits (used under Creative Commons): Amol Patwardhan: Mottled emigrant (plate 1.l) Dinesh Valke: Whirligig beetle (plate 10.h) Jeffrey W. Lotz: Kerria lacca (plate 14.o) Piotr Naskrecki, Bud bug (plate 17.e) Beatriz Moisset: Sweat bee (plate 26.h) Lindsay Condon: Mole cricket (plate 28.l) Ashish Tiple: Common hooktail (plate 29.d) Ashish Tiple: Common clubtail (plate 29.e) Aleksandr: Lacewing larva (plate 34.c) Jeff Holman: Flea (plate 35.j) Kosta Mumcuoglu: Louse (plate 35.m) Erturac: Flea (plate 35.n) Cover: Amyciaea forticeps preying on Oecophylla smargdina, with a kleptoparasitic Phorid fly sharing in the meal. -

Howard Associate Professor of Natural History and Curator Of

INGI AGNARSSON PH.D. Howard Associate Professor of Natural History and Curator of Invertebrates, Department of Biology, University of Vermont, 109 Carrigan Drive, Burlington, VT 05405-0086 E-mail: [email protected]; Web: http://theridiidae.com/ and http://www.islandbiogeography.org/; Phone: (+1) 802-656-0460 CURRICULUM VITAE SUMMARY PhD: 2004. #Pubs: 138. G-Scholar-H: 42; i10: 103; citations: 6173. New species: 74. Grants: >$2,500,000. PERSONAL Born: Reykjavík, Iceland, 11 January 1971 Citizenship: Icelandic Languages: (speak/read) – Icelandic, English, Spanish; (read) – Danish; (basic) – German PREPARATION University of Akron, Akron, 2007-2008, Postdoctoral researcher. University of British Columbia, Vancouver, 2005-2007, Postdoctoral researcher. George Washington University, Washington DC, 1998-2004, Ph.D. The University of Iceland, Reykjavík, 1992-1995, B.Sc. PROFESSIONAL AFFILIATIONS University of Vermont, Burlington. 2016-present, Associate Professor. University of Vermont, Burlington, 2012-2016, Assistant Professor. University of Puerto Rico, Rio Piedras, 2008-2012, Assistant Professor. National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC, 2004-2007, 2010- present. Research Associate. Hubei University, Wuhan, China. Adjunct Professor. 2016-present. Icelandic Institute of Natural History, Reykjavík, 1995-1998. Researcher (Icelandic invertebrates). Institute of Biology, University of Iceland, Reykjavík, 1993-1994. Research Assistant (rocky shore ecology). GRANTS Institute of Museum and Library Services (MA-30-19-0642-19), 2019-2021, co-PI ($222,010). Museums for America Award for infrastructure and staff salaries. National Geographic Society (WW-203R-17), 2017-2020, PI ($30,000). Caribbean Caves as biodiversity drivers and natural units for conservation. National Science Foundation (IOS-1656460), 2017-2021: one of four PIs (total award $903,385 thereof $128,259 to UVM). -

A Summary List of Fossil Spiders

A summary list of fossil spiders compiled by Jason A. Dunlop (Berlin), David Penney (Manchester) & Denise Jekel (Berlin) Suggested citation: Dunlop, J. A., Penney, D. & Jekel, D. 2010. A summary list of fossil spiders. In Platnick, N. I. (ed.) The world spider catalog, version 10.5. American Museum of Natural History, online at http://research.amnh.org/entomology/spiders/catalog/index.html Last udated: 10.12.2009 INTRODUCTION Fossil spiders have not been fully cataloged since Bonnet’s Bibliographia Araneorum and are not included in the current Catalog. Since Bonnet’s time there has been considerable progress in our understanding of the spider fossil record and numerous new taxa have been described. As part of a larger project to catalog the diversity of fossil arachnids and their relatives, our aim here is to offer a summary list of the known fossil spiders in their current systematic position; as a first step towards the eventual goal of combining fossil and Recent data within a single arachnological resource. To integrate our data as smoothly as possible with standards used for living spiders, our list follows the names and sequence of families adopted in the Catalog. For this reason some of the family groupings proposed in Wunderlich’s (2004, 2008) monographs of amber and copal spiders are not reflected here, and we encourage the reader to consult these studies for details and alternative opinions. Extinct families have been inserted in the position which we hope best reflects their probable affinities. Genus and species names were compiled from established lists and cross-referenced against the primary literature. -

SA Spider Checklist

REVIEW ZOOS' PRINT JOURNAL 22(2): 2551-2597 CHECKLIST OF SPIDERS (ARACHNIDA: ARANEAE) OF SOUTH ASIA INCLUDING THE 2006 UPDATE OF INDIAN SPIDER CHECKLIST Manju Siliwal 1 and Sanjay Molur 2,3 1,2 Wildlife Information & Liaison Development (WILD) Society, 3 Zoo Outreach Organisation (ZOO) 29-1, Bharathi Colony, Peelamedu, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu 641004, India Email: 1 [email protected]; 3 [email protected] ABSTRACT Thesaurus, (Vol. 1) in 1734 (Smith, 2001). Most of the spiders After one year since publication of the Indian Checklist, this is described during the British period from South Asia were by an attempt to provide a comprehensive checklist of spiders of foreigners based on the specimens deposited in different South Asia with eight countries - Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. The European Museums. Indian checklist is also updated for 2006. The South Asian While the Indian checklist (Siliwal et al., 2005) is more spider list is also compiled following The World Spider Catalog accurate, the South Asian spider checklist is not critically by Platnick and other peer-reviewed publications since the last scrutinized due to lack of complete literature, but it gives an update. In total, 2299 species of spiders in 67 families have overview of species found in various South Asian countries, been reported from South Asia. There are 39 species included in this regions checklist that are not listed in the World Catalog gives the endemism of species and forms a basis for careful of Spiders. Taxonomic verification is recommended for 51 species. and participatory work by arachnologists in the region. -

CHAPTER ONE a Cladistic Analysis of the Family

University of Pretoria etd – Foord, S H (2005) CHAPTER ONE A Cladistic Analysis of the Family Hersiliidae (Arachnida, Araneae) of the Afrotropical Region Abstract The family Hersiliidae consists of six genera in the Afrotropical region, two of these taxa are newly discovered viz. Tyrotama gen. nov. and Prima gen. nov. Murricia Simon and Neotama Baehr & Baehr are newly recorded for the region. Of the three original genera, Tama, Hersilia, and Hersiliola, the latter two remain. A cladistic analysis based on 48 characters and 22 species, which included nine species that are not Afrotropical, inferred the following phylogeny: ((Hersiliola Tyrotama) (Neotama (Prima (Murricia Hersilia)))). Morphological data supports the monophyly of Tyrotama and the phylogeny suggests that the genus is closely related to Hersiliola. The new genus Prima is weakly supported as the sister taxon of Neotama. Support for the genus Hersilia is weak and synapomorphies that unite six identified species groups within the genus are much more consistent than those that unite Hersilia. However, the genus Hersilia is retained until a comprehensive generic level analysis for the world is conducted. A key to the genera of the Afrotropical Region is provided. Key words: Hersiliidae, phylogeny, Afrotropical Region 6 University of Pretoria etd – Foord, S H (2005) Introduction The Hersiliidae is a small spider family with 141 species and 10 genera excluding results from this study (Platnick 2004; Rheims & Brescovit 2004). The group is characterized by conspicuously long posterior lateral spinnerets, elongated legs and is limited to the tropical and subtropical regions of the world. All hersiliids are arboreal except for the representatives of Hersiliola Thorell, 1870 and Tama Simon, 1882. -

Five Papers on Fossil and Extant Spiders

BEITR. ARANEOL., 13 (2020) Joerg Wunderlich FIVE PAPERS ON FOSSIL AND EXTANT SPIDERS BEITR. ARANEOL., 13 (2020: 1–176) FIVE PAPERS ON FOSSIL AND EXTANT SPIDERS NEW AND RARE FOSSIL SPIDERS (ARANEAE) IN BALTIC AND BUR- MESE AMBERS AS WELL AS EXTANT AND SUBRECENT SPIDERS FROM THE WESTERN PALAEARCTIC AND MADAGASCAR, WITH NOTES ON SPIDER PHYLOGENY, EVOLUTION AND CLASSIFICA- TION JOERG WUNDERLICH, D-69493 Hirschberg, e-mail: [email protected]. Website: www.joergwunderlich.de. – Here a digital version of this book can be found. © Publishing House, author and editor: Joerg Wunderlich, 69493 Hirschberg, Germany. BEITRAEGE ZUR ARANEOLOGIE (BEITR. ARANEOL.), 13. ISBN 978-3-931473-19-8 The papers of this volume are available on my website. Print: Baier Digitaldruck GmbH, Heidelberg. 1 BEITR. ARANEOL., 13 (2020) Photo on the book cover: Dorsal-lateral aspect of the male tetrablemmid spider Elec- troblemma pinnae n. sp. in Burmit, body length 1.5 mm. See the photo no. 17 p. 160. Fossil spider of the year 2020. Acknowledgements: For corrections of parts of the present manuscripts I thank very much my dear wife Ruthild Schöneich. For the professional preparation of the layout I am grateful to Angelika and Walter Steffan in Heidelberg. CONTENTS. Papers by J. WUNDERLICH, with the exception of the paper p. 22 page Introduction and personal note………………………………………………………… 3 Description of four new and few rare spider species from the Western Palaearctic (Araneae: Dysderidae, Linyphiidae and Theridiidae) …………………. 4 Resurrection of the extant spider family Sinopimoidae LI & WUNDERLICH 2008 (Araneae: Araneoidea) ……………………………………………………………...… 19 Note on fossil Atypidae (Araneae) in Eocene European ambers ………………… 21 New and already described fossil spiders (Araneae) of 20 families in Mid Cretaceous Burmese amber with notes on spider phylogeny, evolution and classification; by J. -

Wood MPE 2018.Pdf

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 127 (2018) 907–918 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Next-generation museum genomics: Phylogenetic relationships among palpimanoid spiders using sequence capture techniques (Araneae: T Palpimanoidea) ⁎ Hannah M. Wooda, , Vanessa L. Gonzáleza, Michael Lloyda, Jonathan Coddingtona, Nikolaj Scharffb a Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History, 10th and Constitution Ave. NW, Washington, D.C. 20560-0105, U.S.A. b Biodiversity Section, Center for Macroecology, Evolution and Climate, Natural History Museum of Denmark, University of Copenhagen, Universitetsparken 15, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Historical museum specimens are invaluable for morphological and taxonomic research, but typically the DNA is Ultra conserved elements degraded making traditional sequencing techniques difficult to impossible for many specimens. Recent advances Exon in Next-Generation Sequencing, specifically target capture, makes use of short fragment sizes typical of degraded Ethanol DNA, opening up the possibilities for gathering genomic data from museum specimens. This study uses museum Araneomorphae specimens and recent target capture sequencing techniques to sequence both Ultra-Conserved Elements (UCE) and exonic regions for lineages that span the modern spiders, Araneomorphae, with a focus on Palpimanoidea. While many previous studies have used target capture techniques on dried museum specimens (for example, skins, pinned insects), this study includes specimens that were collected over the last two decades and stored in 70% ethanol at room temperature. Our findings support the utility of target capture methods for examining deep relationships within Araneomorphae: sequences from both UCE and exonic loci were important for resolving relationships; a monophyletic Palpimanoidea was recovered in many analyses and there was strong support for family and generic-level palpimanoid relationships. -

Araneae (Spider) Photos

Araneae (Spider) Photos Araneae (Spiders) About Information on: Spider Photos of Links to WWW Spiders Spiders of North America Relationships Spider Groups Spider Resources -- An Identification Manual About Spiders As in the other arachnid orders, appendage specialization is very important in the evolution of spiders. In spiders the five pairs of appendages of the prosoma (one of the two main body sections) that follow the chelicerae are the pedipalps followed by four pairs of walking legs. The pedipalps are modified to serve as mating organs by mature male spiders. These modifications are often very complicated and differences in their structure are important characteristics used by araneologists in the classification of spiders. Pedipalps in female spiders are structurally much simpler and are used for sensing, manipulating food and sometimes in locomotion. It is relatively easy to tell mature or nearly mature males from female spiders (at least in most groups) by looking at the pedipalps -- in females they look like functional but small legs while in males the ends tend to be enlarged, often greatly so. In young spiders these differences are not evident. There are also appendages on the opisthosoma (the rear body section, the one with no walking legs) the best known being the spinnerets. In the first spiders there were four pairs of spinnerets. Living spiders may have four e.g., (liphistiomorph spiders) or three pairs (e.g., mygalomorph and ecribellate araneomorphs) or three paris of spinnerets and a silk spinning plate called a cribellum (the earliest and many extant araneomorph spiders). Spinnerets' history as appendages is suggested in part by their being projections away from the opisthosoma and the fact that they may retain muscles for movement Much of the success of spiders traces directly to their extensive use of silk and poison. -

Entomological Collections in the Age of Big Data

[**AU: This is the copyedited version of your manuscript; please address the edits/queries directly in this document. It is essential that you use this version of the document, with the Track Changes function enabled, in order for us to distinguish your edits from ours. Please do not copy and paste the content into a “clean” file, as this may result in the introduction of errors as we prepare the manuscript for typesetting. To add reference(s) without renumbering (e.g., between Refs. 12 and 13), use a lowercase letter (e.g., 12a, 12b, etc.) in both text and bibliography. To delete reference(s), delete reference in text and substitute "Deleted in proof" after the number (e.g., 26. Deleted in proof). Do not renumber the references. The typesetter will do this. Abbreviations that were used fewer than two times have been removed. Contiguous hyphens will be converted to dashes in the final version of your manuscript. Finally, colorful reference numbers within the text will be hyperlinked in the online version, but will appear as normal text in the printed version.**] Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2018. 63:X--X https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-031616-035536 Copyright © 2018 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved SHORT ■ DIKOW ■ MOREAU COLLECTIONS IN THE AGE OF BIG DATA ENTOMOLOGICAL COLLECTIONS IN THE AGE OF BIG DATA Andrew Edward Z. Short,1 Torsten Dikow,2 and Corrie S. Moreau3 1Department of Ecology & and Evolutionary Biology and Division of Entomology, Biodiversity Institute, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas 66045, USA; email: [email protected] 2Department of Entomology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20013, USA; email: [email protected] 3Department of Science & and Education, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, Illinois 60605, USA; email: [email protected] ■ Abstract With a million described species and more than half a billion preserved specimens, the large scale of insect collections is unequaled by those of any other group. -

Download Full Article in PDF Format

First fossil Mecysmaucheniidae (Arachnida, Chelicerata, Araneae), from Lower Cretaceous (uppermost Albian) amber of Charente-Maritime, France Erin E. SAUPE Paul A. SELDEN Paleontological Institute, University of Kansas, Lindley hall, 1475 Jayhawk boulevard, Lawrence, KS 66045 (USA) [email protected] [email protected] Saupe E. E. & Selden P. A. 2009. — First fossil Mecysmaucheniidae (Arachnida, Chelicerata, Araneae), from Lower Cretaceous (uppermost Albian) amber of Charente-Maritime, France. Geodiversitas 31 (1) : 49-60. ABSTRACT Th e fi rst known fossil mecysmaucheniid spider, Archaemecys arcantiensis n. gen., n. sp., is described, from Lower Cretaceous (Upper Albian) amber of Charente- Maritime, France. Th is is the fi rst fossil spider to be formally described from French Cretaceous amber and extends the geological record of Mecysmauche- niidae back into the Cretaceous, the family having previously been known only from the Recent. Th e fossil diff ers from other Mecysmaucheniidae in having four, rather than two spinnerets, so it can be considered plesiomorphic with KEY WORDS respect to modern members of the family in this character. Th e amber of the Arachnida, Archingeay-Les Nouillers area is uniquely considered to have a largely preserved Araneae, Mecysmaucheniidae, litter fauna and our specimen corroborates this hypothesis. Archaeidae, and now amber, their sister group the Mecysmaucheniidae, have been found as fossils solely in Cretaceous, the northern hemisphere, yet their Recent distributions are entirely southern France, new genus, hemisphere (Gondwanan). Th e fi nd suggests a former pancontinental distribu- new species. tion of Mecysmaucheniidae. GEODIVERSITAS • 2009 • 31 (1) © Publications Scientifi ques du Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris. www.geodiversitas.com 49 Saupe E.