Arkansauce Issue 3, 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cooking with Friends!

Cooking With Friends! Tasty treats from the Milestone kitchen. Vol. 1 MilestonePA.org INTRODUCTION Last year, I thought “Wouldn’t it be cool if we kept all the recipes we make throughout the year? Maybe we could make a cook book or something…” Well, 12 months and 12 recipes later, Milestone Centers’ Lawrenceville Support Center, Area 6 is proud to present our VERY FIRST volume of Cooking with Friends! Some of these recipes were tricky. Some were a lot of work. But, they were all a fun learning experience. As a group, we worked on important skills like hygiene, cleaning, measuring, counting, reading, ADLs (activities of daily living), fine and gross motor skills and kitchen safety just to name a few. We tried to only include recipes that we made from scratch or with very few premade or boxed ingredients. For instance, a boxed cake might be an ingredient but just making a cake by following the directions on the box didn’t make the cut. Most importantly, we got to taste test every one of the recipes in this book. We hope you enjoy cooking and eating these tasty treats as much as we did! ~Lacy Brooks, Milestone Program Instructor, and Area 6 staff 2 Angel Lush Cake INGREDIENTS • 1 can (20 oz) crushed pineapple • 1 package JELL-O vanilla pudding mix • 1 cup thawed COOL WHIP • 1 package (10 oz) round angel food cake, cut into 3 layers • 10 fresh strawberries 3 DIRECTIONS • Mix dry pudding mix and pineapple. • Gently fold in COOL WHIP • Stack cake layers on a plate, spreading the pudding mixture between each layer and on top of the cake. -

Appetizing Traditions of Arkansas

Pokeweed (Phytolacca americana L.) by M. }. Harvey, illustrator. APPETIZING TRADITIONS OF ARKANSAS Pioneer Arkansas Wedding Stack Cake by Ruth Moore Malone, Editor: A favorite wedding cake in early days when sugar was not plentiful was the stack cake. Folks going to a wedding Holiday Inn International Cook and Travel Book each took along a thin layer of sorghum cake to add to (sixth edition) the stack making the bride's cake. A bride took great Where to Eat in the Ozarks-How it's Cooked pride in the height of her cake for it meant she had many Swiss Holiday Recipes (Ozark Wine Recipes) friends if her wedding cake was high. Some say the footed cake stand became popular because it would make Dogpatch Cook Book (Dogpatch USA) a bride's cake appear to be tall even if she did not have enough friends to bring stack layers for a high cake. The bride's mother furnished applesauce to go between each layer. Sometimes frosting was used to cover the top. Stack Cake This recipe for stack cake layers is similar to a rich cookie dough 11/2 cups sifted flour 1h teaspoon salt A mess of "salit," dipper gourd hoecake, ham 3/4 cup sugar (1/2 sorghum, 1/2 sugar) 112 cup shortening and sweet 'taters, catfish and hushpuppies, wild 2 heaping teaspoons milk duck with rice dressing, chicken and dumplings, 1/2 teaspoon baking powder buttermilk biscuits, sorghum gingerbread, hill coun 1h teaspoon soda try wedding cake and dozens of other recipes reflect 1 egg the heritage of Arkansas. -

2000 Annual Recipe Index

Annual Recipe Index Y our guide to every recipe title in our year-2000 issues ® APPETIZERS Dried Plum-and-Port Bread, Nov 140 Lemon-Honey Drop Cookies, Dec 140 English Muffins, Sept 111 Mocha Double-Fudge Brownies, June 202 Antipasto Bowl, Dec 100 Festive Fruit Soda Bread, Nov 142 Molasses Crackle Cookies, May 210 Artichokes With Roasted-Pepper Dip, Dec 178 Fig-Swirl Coffeecake, Nov 186 Oatmeal Cookies With A-Peel, June 192 Asian-Spiced Pecans, Nov 179 Flaxseed Bread, J/F 168 Ooey-Gooey Peanut Butter-Chocolate Brownies, Cajun Tortilla Chips, J/F 159 Fresh Cranberry Muffins, Dec 128 Sept 156 Celestial Chicken, Mint, and Cucumber Skewers Fresh Fig Focaccia, Aug 152 Peanut Butter-Chocolate Chip Brownies, June 198 With Spring Onion Sauce, July 106 Fruit-and-Nut Bread, J/F 103 Peanut Butter-Crispy Rice Bars, Sept 156 Cosmic Crab Salad With Corn Chips, July 106 Herbed Focaccia, Mar 138 Power Biscotti, Nov 198 Country Chicken Pâté, July 140 Honey Twists, June 197 Raspberry-Cream Cheese Brownies, June 200 Creamy Feta-Spinach Dip, J/F 158 Jalapeño Corn Bread, Nov 122 Raspberry Strippers, Dec 134 Cumin-Spiked Popcorn, July 96 Jamaican Banana Bread, Apr 212 Sesame-Orange Biscotti, Nov 214 Forest-Mushroom Dip, J/F 156 Kim’s Best Pumpkin Bread, Oct 157 Snickerdoodle Biscotti, Nov 202 Hot Bean-and-Cheese Dip, J/F 155 Lavender-Apricot Swirls, June 180 Spicy Oatmeal Crisps, Dec 130 Indian Egg-Roll Strips, J/F 159 Lavender-Honey Loaf, June 182 Toffee Biscotti, Nov 200 Italian Baguette Chips, J/F 156 Lemon-Glazed Zucchini Quick Bread, June 176 Truffle-Iced -

Friends, Stories, Cooking Give Sense of Comfort

A special supplement to ChristmasHerald-Citizen Friends, Kicko stories, cookingff Wednesday, Nov. 27, 2019 give sense of comfort h, I love the the smells comingcoming you,you, our readers. I’m sure yyouou fromfrom the kitchekitchenn this timetime of the DRUCILLA’S will fi ndnd that somesome of ourour favor-favor- yearyear — like the smell of freshfresh LITTLE ites will become youryour favorites.favorites. Obreadbread bakingbaking or thethe aroma ofof HELPERS I am hopinghoping thethe picturespictures we cinnamon and spices.spices. There’s somethingsomething made for this will be okayokay with aboutabout gettinggetting totogethergether withwith ffriendsriends or all thethe readers.readers. I hhaveave tthehe pipic-c- family,family, ssharingharing storstoriesies andand shar-shar- ture ofof me andand mymy granddaugh-granddaugh- inging recipesrecipes that givesgives us a sense ter,ter, Sierra,Sierra, the H-C made for ofof comfort,comfort, especiallyespecially duringduring tthehe thisthis ChristmasChristmas reciperecipe sectionsection holidays.holidays. in 20012001 whenwhen sshehe wwasas aaboutbout 1 One ooff tthehe greatestgreatest neeneedsds pepeo-o- andand a half.half. We were on our wayway pleple havehave isis forfor someone to havehave to KnoxvilleKnoxville lastlast weekweek whenwhen compassioncompassion on them and some-some- DRUCILLA I was thinkingthinking and makingmaking oneone to off erer cocomfortmfort oorr ffriend-riend- RAY notes aboutabout allall thethe recipesrecipes forfor ship.ship. Food links us together,together, this section. We were meetingmeeting especiallyespecially if we needneed comfort.comfort. Sierra,Sierra who is i a culinary arts student at OurOur readersreaders hahaveve ssentent in rreci-eci- PellissippiPellissippi and UT at Knoxville, for lunch at pespes that are their favorites. So Cracker Barrel. -

Tubeset Muffin Batter

IDEAS FOR TubeSet Muffin BATTER 1 CONTENTS BREAKFAST AND CORNBREAD BRUNCH IDEAS APPLICATIONS Breakfast Breads .......... 5 Corn Muffin TubeSet Ideas .......... 22 Blueberry Apricot Torte .......... 6 Blueberry TubeSet Ideas .......... 7-8 Cakes from TubeSet Muffin Batter .......... 9 Lemon Poppy seed Coffee Cake Ideas .......... 10 FINISHING IDEAS .......... 23 Marbled Loaves .......... 11 French Toast and Bageluffins .......... 12 DESSERTS Sunrise Muffin Carrot Cakes .......... 13 Chocolate-Chocolate Chip Ideas .......... 14-15 Cappuccino Chunk Ideas .......... 16 Orange Cranberry and Blueberry Cakes .......... 17 Mocha Thimble Cakes .......... 18 Thimble Cakes .......... 19 Mini Thimble Cakes .......... 20 2 TUBESET BATTER DOES EVEN MORE THAN MAKE MUFFINS! BAKE IN LOAF PANS, SHEET PANS OR BAKEABLE PAPER MOLDS TO ADD VARIETY TO YOUR OFFERINGS AND MOVE MUFFINS INTO DIFFERENT DAY-PARTS. PILLSBURY® TUBESET® MUFFIN BATTERS • Specially formulated to thaw in 3-4 hours in the refrigerator • Just squeeze, bake and serve. No mess. No waste. • Versatile: Use for large or small bake quantities • 15 different flavor varieties • Will be reformulated with no artificial flavors and no colors from artificial sources* *Reformulation change will begin rolling out by Spring 2018 3 EACH MUFFIN FLAVOR IS THE SAME FORMULA ACROSS PACKAGING PLATFORMS. SO TUBESET BLUEBERRY MUFFIN BATTER IS THE SAME FORMULA AS THE FROZEN BLUEBERRY MUFFIN BATTER IN 9 AND 18 LB PAILS. ® PILLSBURY FROZEN BAKED GOODS Muffins - Frozen Batters UPC CODE PRODUCT PACK YIELD Tubeset® ⓊD 10094562080058 Apple Cinnamon 6/3 lb. 144/2 oz. muffins ⓊD 10094562080218 Banana Nut 6/3 lb. 144/2 oz. muffins ⓊD 10094562080263 Blueberry 6/3 lb. 144/2 oz. muffins ⓊD 10094562080955 Cappuccino Chocolate Chunk 6/3 lb. -

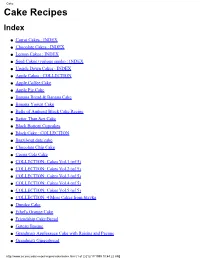

Cake Recipes Index

Cake Cake Recipes Index ● Carrot Cakes : INDEX ● Chocolate Cakes : INDEX ● Lemon Cakes : INDEX ● Seed Cakes (various seeds) : INDEX ● Upside Down Cakes : INDEX ● Apple Cakes : COLLECTION ● Apple Coffee Cake ● Apple Pie Cake ● Banana Bread & Banana Cake ● Banana Yogurt Cake ● Belle of Amherst Black Cake Recipe ● Better Than Sex Cake ● Black Bottom Cupcakes ● Black Cake : COLLECTION ● Brazil-nut date cake ● Chocolate Chip Cake ● Cocoa Cola Cake ● COLLECTION: Cakes Vol.1 (of 5) ● COLLECTION: Cakes Vol.2 (of 5) ● COLLECTION: Cakes Vol.3 (of 5) ● COLLECTION: Cakes Vol.4 (of 5) ● COLLECTION: Cakes Vol.5 (of 5) ● COLLECTION: 4 More Cakes from Stayka ● Dundee Cake ● Ethel's Orange Cake ● Friendship Cake/Bread ● Gateau Basque ● Grandma's Applesauce Cake with Raisins and Pecans ● Grandma's Gingerbread http://www.cs.cmu.edu/~mjw/recipes/cake/index.html (1 of 2) [12/17/1999 10:44:22 AM] Cake ● Helen's Apple Coffee Cake ● Jewish Apple Cake ● Lady Baltimore Cake ● Lamingtons ● Light Fruit Cake ● Liqueur Cakes : COLLECTION ● Macaroon Cake ● Nut Cakes ● Orange Cake ● Peach-Glazed Savarin ● Pineapple Crumbcake ● Pumpkin Cake w/Orange Glaze ● Rum Cake ● Savannah Cream Cake ● Semolina and Yogourt Cake ● Seventh Heaven Cake ● Spice Cake ● Spider Cake ● Yoghurt-Glazed Gingerbread amyl http://www.cs.cmu.edu/~mjw/recipes/cake/index.html (2 of 2) [12/17/1999 10:44:22 AM] Carrot Cakes Carrot Cakes Index ● Carrot Cake (1) ● Carrot Cake (2) ● Carrot Cakes : COLLECTION ● amyl http://www.cs.cmu.edu/~mjw/recipes/cake/carrot-cake/index.html [12/17/1999 10:44:26 AM] Carrot Cake Carrot Cake From: [email protected] (Stephanie da Silva) Date: Wed, 7 Jul 93 9:25:53 CDT Carrot Cake Dry Ingredients (Combine and set aside): 1 1/3 cups flour 1/2 tsp. -

2017 Event Suite Menu

2017 Event suite menu EXECUTIVE CHEF, MONIQUE KING Chef Monique’s suite menu brings a variety of options from timeless STAPLES favorites to menu offerings highlighting LA’s most popular foodie neighborhoods. All carefully prepared to complement your luxury suite experience COOL APPETIZERS CULINARY COLLECTIONS FLATBREAD SAMPLER SO-CAL BARBECUE PACKAGE 49.95 per person, minimum of 12 people • Fresh mozzarella, plum tomato, Kalamata olives Better Be Quick, because this BBQ will be everyone’s favorite! basil leaf finished with a house-made pesto dressing • Genoa salami, mortadella, prosciutto, fresh oregano SEASONED HOUSE-POPPED POPCORN VN shaved Parmigiano-Reggiano, roasted peppers A trio of chili-lime, BBQ and garlic seasonings sun-dried tomato pesto drizzled with light balsamic ST. LOUIS RIBS glaze 12.95 per person Marinated, dry-rubbed and house smoked. Falls right off the bone! MARKET FRESH FRUIT V CHAR GRILLED CHICKEN SALAD Seasonal fruits with Greek yogurt agave orange dip Crunchy romaine and baby kale with hothouse tomato, cucumber, shaved radish 12.95 per person grilled corn, red onions and buttermilk ranch dressing CHEFS GARDEN VEGETABLES V OLD FASHIONED POTATO SALAD Served with buttermilk ranch dressing Sour cream & scallions 12.95 per person SMOKEHOUSE BAKED BEANS ASSORTED SUSHI SAMPLER Six hours in the smoker with brown sugar and spice! Tuna nigiri, salmon nigiri, shrimp nigiri, snapper nigiri SLOW BRAISED BRISKET BARBACOA yellowtail nigiri, spicy tuna, spicy salmon and other Hand rubbed with our house dry rub, smoked and then -

2019 Luxury Suite Menu

2018-2019 LUxURY suite menu COOL APPETIZERS PACKAGES (served for a minimum of six people unless otherwise noted) FAN FAVORITES 49.95 per person, minimum of twelve people ARTISAN MEAT & CHEESE SAMPLER The ultimate day at the event starts with the perfect package of fan favorites and signature dishes Regional cheeses, artisan cured meats with Chef selection of dried fruits, mustards, flat breads, local honeys SNACK TRIO 167.95 per order, serves 10-12 guests DORITOS® COOL RANCH® Flavored Tortilla Chips, house made kettle chips, pretzels FARMSTAND VEGGIES AND DIPS FRESHLY POPPED POPCORN Ranch dipping sauce, red pepper hummus 25.00 per order, serves 10-12 guests MARKET FRESH VEGETABLES Served with buttermilk ranch dressing SANDWICH DUO HAWAIIAN MACARONI SALAD • Fresh mozzarella, plum tomato, Kalamata olive, basil Elbow macaroni, potato, shredded carrots, red onion, hard boiled egg, scallions tossed in cider dressing leaf, drizzled house made pesto dressing FIELD GREEN SALAD • Genoa salami, mortadella, prosciutto, fresh oregano Spring mix lettuce, shredded red cabbage, carrots, cherry tomato, red onion, served with red wine vinaigrette shaved Parmigiano-Reggiano, roasted peppers sun-dried tomato pesto, drizzled balsamic glaze SWEET AND SMOKEY WINGS 13.75 per person STEAKHOUSE BEEF TENDERLOIN MARKET FRESH FRUIT Black peppercorn crusted tenderloin sliced and served chilled with red onion, arugula, tomato, blue cheese Seasonal fruits with Greek yogurt agave orange dip accompanied with house pickled vegetables, horseradish crema, brown mustard, -

Seven Cakes.Pub

Recipes courtesy of www.SouthernPlate.com Seven Cakes Christy Jordan www.SouthernPlate.com © 2008 Christy Jordan, All Rights Reserved Recipes courtesy of www.SouthernPlate.com Life during the depression in rural Alabama wasn’t too different from any other time of year for my people. You see, they were sharecroppers – dirt farmers who didn’t even own their own dirt. They wouldn’t have known if the world had been prosperous, their lives had always been a struggle of hard work and all too often relying on hope for the next meal. This time of year, there wasn’t a whole lot to be thankful for, other than the fact that there wasn’t any cotton to pick. For them, winter was as bleak as the Alabama landscape. In Alabama, we are not often afforded the sight of glistening snow resting atop hills and trees in a winter wonderland. Here, the sky just gets gray and the landscape browns - bare trees, brown grass, and muddy earth where fields lay in wait for spring . as far as the eye can see. My great grandmother had four children and they all lived in a small shack house. Wood was a precious thing and that meant only heating one room. My grandmamma says “it got so cold at night. Mama would heat rocks and wrap ‘em up in old towels and things to put in bed with us but we still got so cold. You didn’t dare get out of that bed unless you just had to”. Families would work all year for the farmer in exchange for monthly rations of staples such as dried beans, flour, and the occasional bit of meat. -

Sweet Treats Around the World This Page Intentionally Left Blank

www.ebook777.com Sweet Treats around the World This page intentionally left blank www.ebook777.com Sweet Treats around the World An Encyclopedia of Food and Culture Timothy G. Roufs and Kathleen Smyth Roufs Copyright 2014 by ABC-CLIO, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The publisher has done its best to make sure the instructions and/or recipes in this book are correct. However, users should apply judgment and experience when preparing recipes, especially parents and teachers working with young people. The publisher accepts no responsibility for the outcome of any recipe included in this volume and assumes no liability for, and is released by readers from, any injury or damage resulting from the strict adherence to, or deviation from, the directions and/or recipes herein. The publisher is not responsible for any readerÊs specific health or allergy needs that may require medical supervision or for any adverse reactions to the recipes contained in this book. All yields are approximations. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Roufs, Timothy G. Sweet treats around the world : an encyclopedia of food and culture / Timothy G. Roufs and Kathleen Smyth Roufs. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61069-220-5 (hard copy : alk. paper) · ISBN 978-1-61069-221-2 (ebook) 1. Food·Encyclopedias. -

MITCHELL COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY Third Quarter 2017

“Our mission is….to collect, preserve, protect and publicly display materials that are historically significant to Mitchell County…and to make its citizens aware of their heritage.” MITCHELL COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY Third Quarter 2017 GREETINGS FROM THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS OF MITCHELL COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY MCHS had six great programs this season, from Daniel Barron’s presentation on the region’s cultural crossroads in April to Chris Hollifield’s history of Harris Schools in September. This year, there will be a Veterans Day program to commemorate the US entry into the First World War 100 years ago. And don’t forget the annual Apple Butter Festival described in this edition of our newsletter! Watch for information on upcoming events, including a Christmas Tour of Historic Mitchell County Homes, and the 2nd annual MCHS History Bee in March. Finally, we’re already putting together a roster for 2018’s programs! Please support Mitchell County Historical Society by attending these events, purchasing our apple butter, ornaments, and books, and also by sending in your tax-deductible membership fees of $20 per individual and $25 family. MCHS 2017 APPLE BUTTER FESTIVAL The Mitchell County Historical Society will hold its 4th annual Apple Butter Festival on Saturday, 10/21/17, from 10:00 to 4:00 at the Bakersville Creek Walk. Members of our Board of Directors and volunteers will be cooking apple butter over an open flame. Watch them stirring the large kettle and enjoy a sample of hot apple butter with fresh biscuit. We will also have jars of apple butter – pints & half pints – for sale. -

Sweet Treats Around the World: an Encyclopedia of Food and Culture

Sweet Treats around the World This page intentionally left blank Sweet Treats around the World An Encyclopedia of Food and Culture Timothy G. Roufs and Kathleen Smyth Roufs Copyright 2014 by ABC-CLIO, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The publisher has done its best to make sure the instructions and/or recipes in this book are correct. However, users should apply judgment and experience when preparing recipes, especially parents and teachers working with young people. The publisher accepts no responsibility for the outcome of any recipe included in this volume and assumes no liability for, and is released by readers from, any injury or damage resulting from the strict adherence to, or deviation from, the directions and/or recipes herein. The publisher is not responsible for any readerÊs specific health or allergy needs that may require medical supervision or for any adverse reactions to the recipes contained in this book. All yields are approximations. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Roufs, Timothy G. Sweet treats around the world : an encyclopedia of food and culture / Timothy G. Roufs and Kathleen Smyth Roufs. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61069-220-5 (hard copy : alk. paper) · ISBN 978-1-61069-221-2 (ebook) 1. Food·Encyclopedias. 2. Food habits·Encyclopedias. 3. International cooking·Encyclopedias.