2006. Making Fire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fire Bow Drill

Making Fire With The Bow Drill When you are first learning bow-drill fire-making, you must make conditions and your bow drill set such that the chance of getting a coal is the greatest. If you do not know the feeling of a coal beginning to be born then you will never be able to master the more difficult scenarios. For this it is best to choose the “easiest woods” and practice using the set in a sheltered location such as a garage or basement, etc. Even if you have never gotten a coal before, it is best to get the wood from the forest yourself. Getting it from a lumber yard is easy but you learn very little. Also, getting wood from natural sources ensures you do not accidentally get pressure-treated wood which, when caused to smoulder, is highly toxic. Here are some good woods for learning with (and good for actual survival use too): ► Eastern White Cedar ► Staghorn Sumac ► Most Willows ► Balsam Fir ► Aspens and Poplars ► Basswood ► Spruces There are many more. These are centered more on the northeastern forest communities of North America. A good tree identification book will help you determine potential fire-making woods. Also, make it a common practice to feel and carve different woods when you are in the bush. A good way to get good wood for learning on is to find a recently fallen branch or trunk that is relatively straight and of about wrist thickness or bigger. Cut it with a saw. It is best if the wood has recently fallen off the tree. -

Foil Rubbings

OUTDOOR ACTIVITIES Fire Lighting, at Home Fire provokes great memories, wistfully Environmental watching the flames dance around. A Awareness guide to safe methods to light a fire, Understand the impact of human activities on the environment. whether it is on tarmac or in the garden. Time: Combine with our food cooking sheets. 40 min plus Remember there should be a purpose to lighting fires to cook Space: or keep warm. Please be careful of where you light fires, Any Outdoor Space, that keep it in control. Never leave a fire unattended and belongs to you supervise children to prevent burns. Make sure you have a Equipment: bucket of water close by to put out any unwanted fires and to Twigs & Sticks, Matches. extinguish at the end. Maybe vaseline / fire lighter, tin or BBQ tray Location: If you’re restricted on space then disposable BBQ trays, traditional metal BBQ’s or even a ‘fray bentos’ tin (wide and shallow)work well to contain the fire. If you have grass in your garden dig up 30cmx30cm square of turf for a small fire. The turf can be replaced later unburnt. Sand, stones or soaking with water around the pit edge can prevent the fire spreading on dry grass. Fuel: To start the fire, easy to light iems would include dry leaves, bark and household items like lint from washing machines, newspaper and cotton wool. Collect a range of twigs and sticks. This may have to be done on a seperate scavenging walk in the local area. Make sure there is a range of thicknesses from little finger, thumb to wrist thickness. -

In the Autumn 2011 Edition of the Quiver I Wrote an Article Touching on the Topic of Survival As It Applies to the Bowhunter

In the Autumn 2011 edition of The Quiver I wrote an article touching on the topic of survival as it applies to the bowhunter. In this article I want to talk about fire specifically and the different types of firestarters and techniques available. Fire is an important element in a survival situation as it provides heat for warmth, drying clothes or cooking as well as a psychological boost and if you’re hunting in a spot where you are one of the prey species it can keep predators away as well. There are many ways to start a fire; some ways relatively easy and some that would only be used as a last resort. There are pros and cons to most of these techniques. The most obvious tool for starting a fire is a match. While this is a great way to start a fire in your fireplace or fire pit I personally don’t like to carry matches in my pack or on my person. They are hard to keep dry and you are limited to one fire per match IF you can light a one match fire every time. It would be easy to run out of matches in a hurry as you are limited in how many you could reasonably carry. A Bic lighter or one of the more expensive windproof lighters is a slightly better choice for the bowhunter to carry. They are easy to use, easy to carry, fairly compact, and last for a reasonable amount of “lights”. They don’t work well when wet but can be dried out fairly easily. -

F I R I N G O P E R a T I O

Summer 2012 ▲ Vol. 2 Issue 2 ▲ Produced and distributed quarterly by the Wildland Fire Lessons Learned Center F I R I N G O P E R A T I O N S What does a good firing show look like? And, what could go wrong ? Once you By Paul Keller t’s an age-old truth. put fire down— Once you put fire down—you can’t take it back. I We all know how this act of lighting the match— you can’t when everything goes as planned—can help you accomplish your objectives. But, unfortunately, once you’ve put that fire on take it back. the ground, you-know-what can also happen. Last season, on seven firing operations—including prescribed fires and wildfires (let’s face it, your drip torch doesn’t know the difference)—things did not go as planned. Firefighters scrambled for safety zones. Firefighters were entrapped. Firefighters got burned. It might serve us well to listen to the firing operation lessons that our fellow firefighters learned in 2011. As we already know, these firing show mishaps—plans gone awry—aren’t choosey about fuel type or geographic area. Last year, these incidents occurred from Arizona to Georgia to South Dakota—basically, all over the map. In Arkansas, on the mid-September Rock Creek Prescribed Fire, that universal theme about your drip torch never distinguishing between a wildfire or prescribed fire is truly hammered home. Here’s what happened: A change in wind speed dramatically increases fire activity. Jackpots of fuel exhibit extreme fire behavior and torching of individual trees. -

On the Evolution of Human Fire Use

ON THE EVOLUTION OF HUMAN FIRE USE by Christopher Hugh Parker A dissertation submitted to the faculty of The University of Utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology The University of Utah May 2015 Copyright © Christopher Hugh Parker 2015 All Rights Reserved The University of Utah Graduate School STATEMENT OF DISSERTATION APPROVAL The dissertation of Christopher Hugh Parker has been approved by the following supervisory committee members: Kristen Hawkes , Chair 04/22/2014 Date Approved James F. O’Connell , Member 04/23/2014 Date Approved Henry Harpending , Member 04/23/2014 Date Approved Andrea Brunelle , Member 04/23/2014 Date Approved Rebecca Bliege Bird , Member Date Approved and by Leslie A. Knapp , Chair/Dean of the Department/College/School of Anthropology and by David B. Kieda, Dean of The Graduate School. ABSTRACT Humans are unique in their capacity to create, control, and maintain fire. The evolutionary importance of this behavioral characteristic is widely recognized, but the steps by which members of our genus came to use fire and the timing of this behavioral adaptation remain largely unknown. These issues are, in part, addressed in the following pages, which are organized as three separate but interrelated papers. The first paper, entitled “Beyond Firestick Farming: The Effects of Aboriginal Burning on Economically Important Plant Foods in Australia’s Western Desert,” examines the effect of landscape burning techniques employed by Martu Aboriginal Australians on traditionally important plant foods in the arid Western Desert ecosystem. The questions of how and why the relationship between landscape burning and plant food exploitation evolved are also addressed and contextualized within prehistoric demographic changes indicated by regional archaeological data. -

ANTHROPOLOGICAL RECORDS Volume 25

ANTHROPOLOGICAL RECORDS Volume 25 ETHNOGRAPHIC NOTES ON THE SOUTHWESTERN POMO BY E. W. GIFFORD UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY AND LOS ANGELES 1967 ETHNOGRAPHIC NOTES ON THE SOUTHWESTERN POMO ETHNOGRAPHIC NOTES ON THE SOUTHWESTERN POMO BY E. W. GIFFORD ANTHROPOLOGICAL RECORDS Volume 25 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PUBLICATIONS ANTHROPOLOGICAL RECORDS Advisory Editors: M. A. Baumhoff, D. J. Crowley, C. J. Erasmus, T. D. McCown, C. W. Meighan, H. P. Phillips, M. G. Smith Volume 25 Approved for publication May 20, 1966 Issued May 29, 1967 Price, $1.50 University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles C alifornia Cambridge University Press London, England Manufactured in the United States of America CONTENTS Introduction ............................................ 1 The Southwestern Pomo in Russian Times: An Account by Kostromitonow ..1 Data Obtained from Herman James ..5 Neighboring Indian Groups .. 5 Informants ..5 Orthography ..6 Habitat .. 7 Village Sites ..7 Ethnobotany ..10 Ethnozoology. .16 Mammals .16 Birds. 17 Reptiles and batrachians .19 Fishes . 19 Insects and other terrestrial invertebrates. 20 Marine invertebrates .20 Culture Element List .21 Notes on culture element list .38 Appendix: Comparative Notes on Two Historic Village Sites by Clement W. Meighan. 46 Works Cited .............................................. 48 [ v ] ETHNOGRAPHIC NOTES ON THE SOUTHWESTERN POMO BY E. W. GIFFORD INTRODUCTION* The Southwestern Pomo were among the most primitive Charles Haupt married a woman from Chibadono of the California aborigines, a fact to be correlated with [ci'?bad6no] (near Plantation and on the same ridge). She their mountainous terrain on a rugged, inhospitable coast. was called Pashikokoya [pasilk6?koya? ], "cocoon woman" Their low culture may be contrasted with the richer cul- (pashikoyoyu [pa'si-oyo-yu], cocoon used on shaman' s ture of the Pomo of the Russian River Valley and Clear rattle; ya?, personal suffix), but her English name was Lake, environments which offered opportunities for Molly. -

Low-Impact Living Initiative

firecraft what is it? It's starting and managing fire, which requires fuel, oxygen and ignition. The more natural methods usually progress from a spark to an ember to a flame in fine, dry material (tinder), to small, thin pieces of wood (kindling) and then to firewood. Early humans collected embers from forest fires, lightning strikes and even volcanic activity. Archaeological evidence puts the first use of fire between 200-400,000 years ago – a time that corresponds to a change in human physique consistent with food being cooked - e.g. smaller stomachs and jaws. The first evidence of people starting fires is from around 10,000 years ago. Here are some ways to start a fire. Friction: rubbing things together to create friction Sitting around a fire has been a relaxing, that generates heat and produces embers. An comforting and community-building activity for example is a bow-drill, but any kind of friction will many millennia. work – e.g. a fire-plough, involving a hardwood stick moving in a groove in a piece of softwood. what are the benefits? Percussion: striking things together to make From an environmental perspective, the more sparks – e.g. flint and steel. The sharpness of the natural the method the better. For example, flint creates sparks - tiny shards of hot steel. strikers, fire pistons or lenses don’t need fossil Compression: fire pistons are little cylinders fuels or phosphorus, which require the highly- containing a small amount of tinder, with a piston destructive oil and chemical industries, and that is pushed hard into the cylinder to compress friction methods don’t require the mining, factories the air in it, which raises pressure and and roads required to manufacture anything at all. -

Fire Before Matches

Fire before matches by David Mead 2020 Sulang Language Data and Working Papers: Topics in Lexicography, no. 34 Sulawesi Language Alliance http://sulang.org/ SulangLexTopics034-v2 LANGUAGES Language of materials : English ABSTRACT In this paper I describe seven methods for making fire employed in Indonesia prior to the introduction of friction matches and lighters. Additional sections address materials used for tinder, the hearth and its construction, some types of torches and lamps that predate the introduction of electricity, and myths about fire making. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction; 2 Traditional fire-making methods; 2.1 Flint and steel strike- a-light; 2.2 Bamboo strike-a-light; 2.3 Fire drill; 2.4 Fire saw; 2.5 Fire thong; 2.6 Fire plow; 2.7 Fire piston; 2.8 Transporting fire; 3 Tinder; 4 The hearth; 5 Torches and lamps; 5.1 Palm frond torch; 5.2 Resin torch; 5.3 Candlenut torch; 5.4 Bamboo torch; 5.5 Open-saucer oil lamp; 5.6 Footed bronze oil lamp; 5.7 Multi-spout bronze oil lamp; 5.8 Hurricane lantern; 5.9 Pressurized kerosene lamp; 5.10 Simple kerosene lamp; 5.11 Candle; 5.12 Miscellaneous devices; 6 Legends about fire making; 7 Additional areas for investigation; Appendix: Fire making in Central Sulawesi; References. VERSION HISTORY Version 2 [13 June 2020] Minor edits; ‘candle’ elevated to separate subsection. Version 1 [12 May 2019] © 2019–2020 by David Mead All Rights Reserved Fire before matches by David Mead Down to the time of our grandfathers, and in some country homes of our fathers, lights were started with these crude elements—flint, steel, tinder—and transferred by the sulphur splint; for fifty years ago matches were neither cheap nor common. -

Geochemical Evidence for the Control of Fire by Middle Palaeolithic Hominins Alex Brittingham 1*, Michael T

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Geochemical Evidence for the Control of Fire by Middle Palaeolithic Hominins Alex Brittingham 1*, Michael T. Hren 2,3, Gideon Hartman1,4, Keith N. Wilkinson5, Carolina Mallol6,7,8, Boris Gasparyan9 & Daniel S. Adler1 The use of fre played an important role in the social and technological development of the genus Homo. Most archaeologists agree that this was a multi-stage process, beginning with the exploitation of natural fres and ending with the ability to create fre from scratch. Some have argued that in the Middle Palaeolithic (MP) hominin fre use was limited by the availability of fre in the landscape. Here, we present a record of the abundance of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), organic compounds that are produced during the combustion of organic material, from Lusakert Cave, a MP site in Armenia. We fnd no correlation between the abundance of light PAHs (3–4 rings), which are a major component of wildfre PAH emissions and are shown to disperse widely during fre events, and heavy PAHs (5–6 rings), which are a major component of particulate emissions of burned wood. Instead, we fnd heavy PAHs correlate with MP artifact density at the site. Given that hPAH abundance correlates with occupation intensity rather than lPAH abundance, we argue that MP hominins were able to control fre and utilize it regardless of the variability of fres in the environment. Together with other studies on MP fre use, these results suggest that the ability of hominins to manipulate fre independent of exploitation of wildfres was spatially variable in the MP and may have developed multiple times in the genus Homo. -

Fire Making? No Problem, My "Fireman" and Buddy "Bow" Beauchamp Will Be Happy to Try to Help Ya Out

FREE TIPS, TRICKS & IDEAS Fire Making Out of all the survival skills you need to master, I firmly believe fire making" is the most important. Why? A fire will give you warmth when it's cold, chilly, and downright freezing outside. A fire will provide you light during darkness so you can see to do other things. A fire will allow you to cook your meals and boil water so you can consume them safely. A fire will dry out your clothes when they've become wet so you won't get sick. A fire will provide a way to signal for help, both, during darkness and daylight hours. A fire will protect you from wild critters and help keep the "boggy man" away at night too. So the bottom line is by NOT knowing how to make a fire, it could mean the difference between "life" and "death" especially in a cold weather environment. And so allow me to cover briefly what other survival sites say about fire making... TO CREATE FIRE: You need 3 x elements - heat, fuel, & oxygen, and in sufficient quantities and correct ratios too. Because if you use too much of one and not enough of the other(s) you'll produce either (a) no fire, (b) too much fire, or (c) a smoking fire. WHEN SELECTING A FIRE SITE: Choose a location where there's plenty of wood so you don't have to wander far to gather it. And if it's windy or raining, either select a place that'll provide protection against these elements or make a windbreaker out of rocks and/or logs. -

AL Kroeber and Catharine Holt Source

Masks and Moieties as a Culture Complex. Author(s): A. L. Kroeber and Catharine Holt Source: The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 50 (Jul. - Dec., 1920), pp. 452-460 Published by: Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2843493 Accessed: 01-02-2016 04:49 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wiley and Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 204.235.148.92 on Mon, 01 Feb 2016 04:49:06 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 452 MASKS AND MOIETIES AS A CULTURE COMPLEX. By A. L. KROEBERAND CATHARINEHOLT. IN 1905, Graebnerand Ankermannpublished synchronous articlesL in which they distinguisheda nlumberof successivelayers of culturein Oceania and Africa. This scheme Graebnersubsequently developed in an essay which traced at least some of these culturestrata as far as America.2 Graebner'stheory has been accepted, with or without reservations,by a number of authorities,including Foy,3 W. -

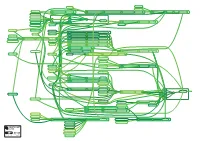

A1128 Able to Light a Fire Map of Influence

11591: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF A LIMPET SHELL 12278: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF A SAW 12113: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF A MUSSEL SHELL 09112: A HUMAN BEING CUSTOMER 09475: A HUMAN BEING IN 12729: A HUMAN BEING IN 12281: A HUMAN BEING IN OF WH SMITH OR OR AND OR OR POSSESSION OF A ELASTIC BAND POSSESSION OF A WOOD WASHER AND OR POSSESSION OF A FIRE BOW DRILL FIRE LIGHTER 10630: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF CHERRY TREE OUTER BARK 12394: A HUMAN BEING IN OR POSSESSION OF A RIBWORT PLANTAIN PLANT LEAF 11946: A HUMAN BEING IN OR AND OR POSSESSION OF STINGING NETTLE PLANT BARK 09477: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF CORDAGE 11550: A HUMAN BEING IN AND OR 10437: A HUMAN BEING IN OR AND POSSESSION OF A BOW POSSESSION OF WHITE WILLOW TREE INNER BARK 13740: A HUMAN BEING IN 00924: A HUMAN BEING USER 10197: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF SKIN BUYER OF TRADE-IT POSSESSION OF SWEET CHESNUT TREE INNER BARK 10607: A HUMAN BEING IN 10086: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF RASPBERRY PLANT BARK POSSESSION OF ASH TREE WOOD 09148: A HUMAN BEING IN POSSESSION OF AN OPTICAL LENS 09472: A HUMAN BEING IN AND OR POSSESSION OF A SUNLIGHT FIRE LIGHTER 09149: A HUMAN BEING LOCATED 01552: A HUMAN BEING IN IN DIRECT SUNLIGHT POSSESSION OF A KNIFE 09471: A HUMAN BEING IN 09720: A HUMAN BEING IN AND OR POSSESSION OF A FIRE DRILL FIRE POSSESSION OF LIME TREE WOOD LIGHTER 09479: A HUMAN BEING IN 10314: A HUMAN BEING IN 09965: A HUMAN BEING IN OR OR AND OR POSSESSION OF A FIRE PLOUGH FIRE POSSESSION OF HAWTHORN TREE WOOD POSSESSION OF A WOOD ROD LIGHTER 10182: