Belarus Country Report BTI 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Belarus Country Report BTI 2014

BTI 2014 | Belarus Country Report Status Index 1-10 4.31 # 101 of 129 Political Transformation 1-10 3.93 # 99 of 129 Economic Transformation 1-10 4.68 # 90 of 129 Management Index 1-10 2.80 # 119 of 129 scale score rank trend This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2014. It covers the period from 31 January 2011 to 31 January 2013. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2014 — Belarus Country Report. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2014. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. BTI 2014 | Belarus 2 Key Indicators Population M 9.5 HDI 0.793 GDP p.c. $ 15592.3 Pop. growth1 % p.a. -0.1 HDI rank of 187 50 Gini Index 26.5 Life expectancy years 70.7 UN Education Index 0.866 Poverty3 % 0.1 Urban population % 75.4 Gender inequality2 - Aid per capita $ 8.8 Sources: The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2013 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2013. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $2 a day. Executive Summary Belarus faced one the greatest challenges of the Lukashenka presidency with the economic shocks that swept the country in 2011. The government’s own policies of politically motivated increases in state salaries and directed lending resulted in a balance of payments crisis, a massive decrease in central bank reserves, a currency crisis as queues formed at banks to change Belarusian rubles into dollars or euros, rampant hyperinflation, a devaluation of the national currency, and a significant drop in real incomes for Belarusian households. -

The EU and Belarus – a Relationship with Reservations Dr

BELARUS AND THE EU: FROM ISOLATION TOWARDS COOPERATION EDITED BY DR. HANS-GEORG WIECK AND STEPHAN MALERIUS VILNIUS 2011 UDK 327(476+4) Be-131 BELARUS AND THE EU: FROM ISOLATION TOWARDS COOPERATION Authors: Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck, Dr. Vitali Silitski, Dr. Kai-Olaf Lang, Dr. Martin Koopmann, Andrei Yahorau, Dr. Svetlana Matskevich, Valeri Fadeev, Dr. Andrei Kazakevich, Dr. Mikhail Pastukhou, Leonid Kalitenya, Alexander Chubrik Editors: Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck, Stephan Malerius This is a joint publication of the Centre for European Studies and the Konrad- Adenauer-Stiftung. This publication has received funding from the European Parliament. Sole responsibility for facts or opinions expressed in this publication rests with the authors. The Centre for European Studies, the Konrad-Adenauer- Stiftung and the European Parliament assume no responsibility either for the information contained in the publication or its subsequent use. ISBN 978-609-95320-1-1 © 2011, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V., Sankt Augustin / Berlin © Front cover photo: Jan Brykczynski CONTENTS 5 | Consultancy PROJECT: BELARUS AND THE EU Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck 13 | BELARUS IN AN INTERnational CONTEXT Dr. Vitali Silitski 22 | THE EU and BELARUS – A Relationship WITH RESERvations Dr. Kai-Olaf Lang, Dr. Martin Koopmann 34 | CIVIL SOCIETY: AN analysis OF THE situation AND diRECTIONS FOR REFORM Andrei Yahorau 53 | Education IN BELARUS: REFORM AND COOPERation WITH THE EU Dr. Svetlana Matskevich 70 | State bodies, CONSTITUTIONAL REALITY AND FORMS OF RULE Valeri Fadeev 79 | JudiciaRY AND law -

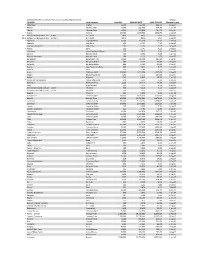

Maximum Monthly Stipend Rates For

MAXIMUM MONTHLY STIPEND RATES FOR FELLOWS AND SCHOLARS Jul 2020 COUNTRY Local Currency Local DSA MAX RES RATE MAX TRV RATE Effective % date * Afghanistan Afghani 12,600 132,300 198,450 1-Aug-07 * Albania Albania Lek(e) 14,000 220,500 330,750 1-Jan-05 Algeria Algerian Dinar 31,600 331,800 497,700 1-Aug-07 * Angola Kwanza 133,000 1,396,500 2,094,750 1-Aug-07 #N/A Antigua and Barbuda (1 Apr. - 30 Nov.) E.C. Dollar #N/A #N/A #N/A 1-Aug-07 #N/A Antigua and Barbuda (1 Dec. - 31 Mar.) E.C. Dollar #N/A #N/A #N/A 1-Aug-07 * Argentina Argentine Peso 18,600 153,450 230,175 1-Jan-05 Australia AUL Dollar 453 4,757 7,135 1-Aug-07 Australia - Academic AUL Dollar 453 1,200 7,135 1-Aug-07 * Austria Euro 261 2,741 4,111 1-Aug-07 * Azerbaijan (new)Azerbaijan Manat 239 1,613 2,420 1-Jan-05 Bahrain Bahraini Dinar 106 2,226 3,180 1-Jan-05 Bahrain - Academic Bahraini Dinar 106 1,113 1,670 1-Aug-07 Bangladesh Bangladesh Taka 12,400 130,200 195,300 1-Aug-07 Barbados Barbados Dollar 880 9,240 13,860 1-Aug-07 Barbados Barbados Dollar 880 9,240 13,860 1-Aug-07 * Belarus New Belarusian Ruble 600 5,850 8,775 1-Jan-06 Belgium Euro 338 3,549 5,324 1-Aug-07 Benin CFA Franc(XOF) 123,000 1,291,500 1,937,250 1-Aug-07 Bhutan Bhutan Ngultrum 7,290 76,545 114,818 1-Aug-07 * Bolivia Boliviano 1,200 10,800 16,200 1-Jan-07 * Bosnia and Herzegovina Convertible Mark 279 3,557 5,336 1-Jan-05 Botswana Botswana Pula 2,220 23,310 34,965 1-Aug-07 Brazil Brazilian Real 530 4,373 6,559 1-Jan-05 British Virgin Islands (16 Apr. -

The Monetary Legacy of the Soviet Union / Patrick Conway

ESSAYS IN INTERNATIONAL FINANCE ESSAYS IN INTERNATIONAL FINANCE are published by the International Finance Section of the Department of Economics of Princeton University. The Section sponsors this series of publications, but the opinions expressed are those of the authors. The Section welcomes the submission of manuscripts for publication in this and its other series. Please see the Notice to Contributors at the back of this Essay. The author of this Essay, Patrick Conway, is Professor of Economics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He has written extensively on the subject of structural adjustment in developing and transitional economies, beginning with Economic Shocks and Structural Adjustment: Turkey after 1973 (1987) and continuing, most recently, with “An Atheoretic Evaluation of Success in Structural Adjustment” (1994a). Professor Conway has considerable experience with the economies of the former Soviet Union and has made research visits to each of the republics discussed in this Essay. PETER B. KENEN, Director International Finance Section INTERNATIONAL FINANCE SECTION EDITORIAL STAFF Peter B. Kenen, Director Margaret B. Riccardi, Editor Lillian Spais, Editorial Aide Lalitha H. Chandra, Subscriptions and Orders Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Conway, Patrick J. Currency proliferation: the monetary legacy of the Soviet Union / Patrick Conway. p. cm. — (Essays in international finance, ISSN 0071-142X ; no. 197) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-88165-104-4 (pbk.) : $8.00 1. Currency question—Former Soviet republics. 2. Monetary policy—Former Soviet republics. 3. Finance—Former Soviet republics. I. Title. II. Series. HG136.P7 no. 197 [HG1075] 332′.042 s—dc20 [332.4′947] 95-18713 CIP Copyright © 1995 by International Finance Section, Department of Economics, Princeton University. -

Holocaust Memorial Days an Overview of Remembrance and Education in the OSCE Region

Holocaust Memorial Days An overview of remembrance and education in the OSCE region 27 January 2015 Updated October 2015 Table of Contents Foreword .................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 2 Albania ................................................................................................................................. 13 Andorra ................................................................................................................................. 14 Armenia ................................................................................................................................ 16 Austria .................................................................................................................................. 17 Azerbaijan ............................................................................................................................ 19 Belarus .................................................................................................................................. 21 Belgium ................................................................................................................................ 23 Bosnia and Herzegovina ....................................................................................................... 25 Bulgaria ............................................................................................................................... -

Countries Codes and Currencies 2020.Xlsx

World Bank Country Code Country Name WHO Region Currency Name Currency Code Income Group (2018) AFG Afghanistan EMR Low Afghanistan Afghani AFN ALB Albania EUR Upper‐middle Albanian Lek ALL DZA Algeria AFR Upper‐middle Algerian Dinar DZD AND Andorra EUR High Euro EUR AGO Angola AFR Lower‐middle Angolan Kwanza AON ATG Antigua and Barbuda AMR High Eastern Caribbean Dollar XCD ARG Argentina AMR Upper‐middle Argentine Peso ARS ARM Armenia EUR Upper‐middle Dram AMD AUS Australia WPR High Australian Dollar AUD AUT Austria EUR High Euro EUR AZE Azerbaijan EUR Upper‐middle Manat AZN BHS Bahamas AMR High Bahamian Dollar BSD BHR Bahrain EMR High Baharaini Dinar BHD BGD Bangladesh SEAR Lower‐middle Taka BDT BRB Barbados AMR High Barbados Dollar BBD BLR Belarus EUR Upper‐middle Belarusian Ruble BYN BEL Belgium EUR High Euro EUR BLZ Belize AMR Upper‐middle Belize Dollar BZD BEN Benin AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BTN Bhutan SEAR Lower‐middle Ngultrum BTN BOL Bolivia Plurinational States of AMR Lower‐middle Boliviano BOB BIH Bosnia and Herzegovina EUR Upper‐middle Convertible Mark BAM BWA Botswana AFR Upper‐middle Botswana Pula BWP BRA Brazil AMR Upper‐middle Brazilian Real BRL BRN Brunei Darussalam WPR High Brunei Dollar BND BGR Bulgaria EUR Upper‐middle Bulgarian Lev BGL BFA Burkina Faso AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BDI Burundi AFR Low Burundi Franc BIF CPV Cabo Verde Republic of AFR Lower‐middle Cape Verde Escudo CVE KHM Cambodia WPR Lower‐middle Riel KHR CMR Cameroon AFR Lower‐middle CFA Franc XAF CAN Canada AMR High Canadian Dollar CAD CAF Central African Republic -

Maximum Monthly Stipend Rates for Fellows And

MAXIMUM MONTHLY STIPEND RATES FOR FELLOWS AND SCHOLARS Sep 2020 COUNTRY Local Currency Local DSA MAX RES RATE MAX TRV RATE Effective % date Afghanistan Afghani 12,500 131,250 196,875 1-Aug-07 * Albania Albania Lek(e) 13,100 206,325 309,488 1-Jan-05 Algeria Algerian Dinar 31,600 331,800 497,700 1-Aug-07 * Angola Kwanza 134,000 1,407,000 2,110,500 1-Aug-07 #N/A Antigua and Barbuda (1 Apr. - 30 Nov.) E.C. Dollar #N/A #N/A #N/A 1-Aug-07 #N/A Antigua and Barbuda (1 Dec. - 31 Mar.) E.C. Dollar #N/A #N/A #N/A 1-Aug-07 * Argentina Argentine Peso 19,700 162,525 243,788 1-Jan-05 Australia AUL Dollar 453 4,757 7,135 1-Aug-07 Australia - Academic AUL Dollar 453 1,200 7,135 1-Aug-07 Austria Euro 261 2,741 4,111 1-Aug-07 Azerbaijan (new)Azerbaijan Manat 239 1,613 2,420 1-Jan-05 Bahrain Bahraini Dinar 106 2,226 3,180 1-Jan-05 Bahrain - Academic Bahraini Dinar 106 1,113 1,670 1-Aug-07 Bangladesh Bangladesh Taka 12,400 130,200 195,300 1-Aug-07 Barbados Barbados Dollar 880 9,240 13,860 1-Aug-07 Barbados Barbados Dollar 880 9,240 13,860 1-Aug-07 * Belarus New Belarusian Ruble 680 6,630 9,945 1-Jan-06 Belgium Euro 338 3,549 5,324 1-Aug-07 Benin CFA Franc(XOF) 123,000 1,291,500 1,937,250 1-Aug-07 Bhutan Bhutan Ngultrum 7,290 76,545 114,818 1-Aug-07 Bolivia Boliviano 1,180 10,620 15,930 1-Jan-07 * Bosnia and Herzegovina Convertible Mark 264 3,366 5,049 1-Jan-05 Botswana Botswana Pula 2,220 23,310 34,965 1-Aug-07 Brazil Brazilian Real 530 4,373 6,559 1-Jan-05 British Virgin Islands (16 Apr. -

Belarusian Opposition Presidential Candidate Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya

Thank you, Mr. Chairman, Today my country, Belarus, is in turmoil. Peaceful protesters are being illegally detained, beaten, and imprisoned. The protests themselves started after a cynical and blatant attempt by Mr. Lukashenko to steal the votes of the people. The demands of the nation are simple: immediate termination of violence and threats by the regime, immediate release of all political prisoners, and free and fair election. There is only one obstacle to these demands being met. This obstacle is Mr. Lukashenko, a man desperately clinging onto power and refusing to listen to his people and his own state officials. A nation can not and should not be a hostage to one man's thirst for power. And it won't. Belarusians have woken up. The point of no return has passed. This is manifested by now daily demonstrations of hundreds of thousands all across Belarus, despite police brutality and blatant disregard for Belarusian laws and international norms. This is manifested by the strikes across the largest factories and state-owned companies in Belarus, despite intimidation and in some cases unlawful layoffs. This is manifested by all the strata of our society and all the political spectrum demanding the one and the same thing. The regime of Alexander Lukashenko is morally bankrupt, legally questionable and simply untenable in the eyes of our nation. The United Nations was created as a formal body of the whole international community in order to promote and encourage respect for human rights and for fundamental freedoms for all. In 1945 Belarus was one of the founding members of the United Nations. -

BELARUS Restrictions on the Political and Civil Rights of Citizens Following the 2010 Presidential Election

BELARUS Restrictions on the Political and Civil Rights of Citizens Following the 2010 Presidential Election of person. Article 4: No one shall be held in slavery Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms. Article 5: No one shall be subjected to in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. Article 6: Everyone has the right to recognition spirit of brotherhood. Article 2: Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, everywhere as a person before the law. Article 7: All are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimi- without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, nation to equal protection of the law. All are entitled to equal protection against any discrimination in violation of this national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the Declaration and against any incitement to such discrimination. Article 8: Everyone has the right to an effective rem- basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person edy by the competent national tribunals for acts violating the fundamental rights granted him by the constitution or belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty. by law. Article 9: No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest, Article 3: Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security June 2011 564a Uladz Hrydzin © This report has been produced with the support of the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA). -

Straddling Russia and Europe

Straddling Russia and Europe A Compendium of Recent Jamestown Analysis on Belarus January 2013 Straddling Russia and Europe A Compendium of Recent Jamestown Analysis on Belarus Washington, D.C. January 2013 THE JAMESTOWN FOUNDATION Published in the United States by The Jamestown Foundation 1111 16th St. N.W. Suite 320 Washington, D.C. 20036 http://www.jamestown.org Copyright © The Jamestown Foundation, January 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this report may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written consent. For copyright permissions information, contact The Jamestown Foundation. The views expressed in this report are those of the contributing authors and not necessarily those of The Jamestown Foundation. For more information on this report or The Jamestown Foundation, email [email protected]. JAMESTOWN’S MISSION The Jamestown Foundation’s mission is to inform and educate policymakers and the broader policy community about events and trends in those societies, which are strategically or tactically important to the United States and which frequently restrict access to such information. Utilizing indigenous and primary sources, Jamestown’s material is delivered without political bias, filter or agenda. It is often the only source of information that should be, but is not always, available through official or intelligence channels, especially with regard to Eurasia and terrorism. Origins Launched in 1984 after Jamestown’s late president and founder William Geimer’s work with Arkady Shevchenko, the highest-ranking Soviet official ever to defect when he left his position as undersecretary general of the United Nations, the Jamestown Foundation rapidly became the leading source of information about the inner workings of closed totalitarian societies. -

Banking Sector and Economy of CEE Countries: Development Features and Correlation

Centre for Research on Settlements and Urbanism Journal of Settlements and Spatial Planning J o u r n a l h o m e p a g e: http://jssp.reviste.ubbcluj.ro Banking Sector and Economy of CEE Countries: Development Features and Correlation Iurii UMANTSIV 1, Olena ISHCHENKO 1 1 Kyiv National University of Trade and Economics, Faculty of Economics, Management and Psychology, Department of Economic Theory and Competition Policy, Kyiv, UKRAINE E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] DOI: 10.24193/JSSP.2017.1.05 https://doi.org/10.24193/JSSP.2017.1.05 K e y w o r d s: economy of CEE country, banking system, financial sector, role of banks, correlation between GDP and bank investments, EU operational programs, CEE countries, banking sector development A B S T R A C T This research focuses on the analysis of current trends in the banking sector of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), and on its role in the development of the economy. This region is represented by countries situated at different levels of development and types of economic system. The following countries are analyzed: Bulgaria, Poland, Romania, the Republic of Belarus and Ukraine. The article starts with a general description of the economy of each of the five countries listed above, followed by a discussion of main trends of their development and a comparison of these states based on the status of their socioeconomic development. The study will also examine the banking systems of each of these countries looking at the types of banks that are present on the market, capital ownership, and market share, as well as the main indicators of soundness of the banking system. -

EU-Belarus Relations: State of Play Human Rights Situation and Ryanair Flight Diversion

BRIEFING EU-Belarus relations: State of play Human rights situation and Ryanair flight diversion SUMMARY The falsified presidential elections of August 2020, and the brutal crackdown against peacefully protesting Belarusians, led to the isolation of the Aliaksandr Lukashenka regime. Despite the possibility of starting dialogue with the democratic opposition and Belarusian society, Aliaksandr Lukashenka chose another path, involving continued brutal repression of the country's citizens. The worsening human rights situation and hijacking of Ryanair flight FR 4978 provoked a response from the EU, including a ban on Belarusian air carriers landing in or overflying the EU, a major extension of the list of people and entities already subject to sanctions, and the introduction of sanctions on key sectors of the Belarusian economy. The EU policy also demonstrates a readiness to support a future democratic Belarus. In this respect, the European Commission presented the outline of a comprehensive plan of economic support for democratic Belarus, worth up to €3 billion. The European Parliament is playing an active part in shaping the EU's response. Parliament does not recognise Lukashenka's presidency and is speaking out on human rights abuses in Belarus. The Belarusian democratic opposition, which was awarded the 2020 Sakharov Prize, is frequently invited to speak for the Belarusian people in the European Parliament. IN THIS BRIEFING Background Current trends in the human rights situation in Belarus Ryanair flight forced to land in Belarus The fourth package of sanctions Outline of the Commission's comprehensive plan of economic support for a future democratic Belarus Russian influence in Belarus International reactions EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service Author: Jakub Przetacznik Members' Research Service PE 696.177 – July 2021 EN EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service Background EU-Belarus relations during Aliaksandr Lukashenka's long presidency, which began in 1994, have fluctuated.