Storja 2001.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction – Grand Harbour Marina

introduction – grand harbour marina Grand Harbour Marina offers a stunning base in historic Vittoriosa, Today, the harbour is just as sought-after by some of the finest yachts Malta, at the very heart of the Mediterranean. The marina lies on in the world. Superbly serviced, well sheltered and with spectacular the east coast of Malta within one of the largest natural harbours in views of the historic three cities and the capital, Grand Harbour is the world. It is favourably sheltered with deep water and immediate a perfect location in the middle of the Mediterranean. access to the waterfront, restaurants, bars and casino. With berths for yachts up to 100m (325ft) in length, the marina offers The site of the marina has an illustrious past. It was originally used all the world-class facilities you would expect from a company with by the Knights of St John, who arrived in Malta in 1530 after being the maritime heritage of Camper & Nicholsons. exiled by the Ottomans from their home in Rhodes. The Galley’s The waters around the island are perfect for a wide range of activities, Creek, as it was then known, was used by the Knights as a safe including yacht cruising and racing, water-skiing, scuba diving and haven for their fleet of galleons. sports-fishing. Ashore, amid an environment of outstanding natural In the 1800s this same harbour was re-named Dockyard Creek by the beauty, Malta offers a cosmopolitan selection of first-class hotels, British Colonial Government and was subsequently used as the home restaurants, bars and spas, as well as sports pursuits such as port of the British Mediterranean Fleet. -

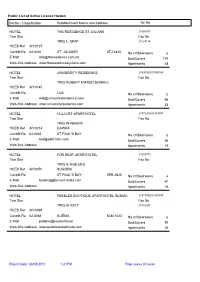

Public List of Active Licence Holders Tel No Sector / Classification

Public List of Active Licence Holders Sector / Classification Establishment Name and Address Tel No HOTEL THE RESIDENCE ST JULIANS 21360031 Two Star Fax No TRIQ L. APAP 21374114 HCEB Ref AH/0137 Contrib Ref 02-0044 ST. JULIAN'S STJ 3325 No Of Bedrooms 0 E Mail [email protected] Bed/Covers 124 Web-Site Address www.theresidencestjulians.com Apartments 48 HOTEL UNIVERSITY RESIDENCE 21430360/21436168 Two Star Fax No TRIQ ROBERT MIFSUD BONNICI HCEB Ref AH/0145 Contrib Ref LIJA No Of Bedrooms 0 E Mail [email protected] Bed/Covers 66 Web-Site Address www.universityresidence.com Apartments 33 HOTEL HULI CRT APARTHOTEL 21572200/21583741 Two Star Fax No TRIQ IN-NAKKRI HCEB Ref AH/0214 QAWRA Contrib Ref 02-0069 ST.PAUL'S BAY No Of Bedrooms 0 E Mail [email protected] Bed/Covers 56 Web-Site Address Apartments 19 HOTEL FOR REST APARTHOTEL 21575773 Two Star Fax No TRIQ IL-HGEJJEG HCEB Ref AH/0370 BUGIBBA Contrib Ref ST.PAUL'S BAY SPB 2825 No Of Bedrooms 4 E Mail [email protected] Bed/Covers 40 Web-Site Address Apartments 16 HOTEL PEBBLES BOUTIQUE APARTHOTEL SLIEMA 21311889/21335975 Two Star Fax No TRIQ IX-XATT 21316907 HCEB Ref AH/0395 Contrib Ref 02-0068 SLIEMA SLM 1022 No Of Bedrooms 0 E Mail [email protected] Bed/Covers 92 Web-Site Address www.pebbleshotelmalta.com Apartments 26 Report Date: 30/08/2019 1-21PM Page xxxxx of xxxxx Public List of Active Licence Holders Sector / Classification Establishment Name and Address Tel No HOTEL ALBORADA APARTHOTEL (BED & BREAKFAST) 21334619/21334563 Two Star 28 Fax No TRIQ IL-KBIRA -

Module 1 Gozo Today

Unit 1 - Gozo Today Josianne Vella Preamble: This first unit brings a brief overview of the Island’s physical and human geography, including a brief historic overview of the economic activities in Gozo. Various means of access to, and across the island as well as some of the major places of interest have been interspersed with information on the Island’s customs and unique language. ‘For over 5,000 years people have lived here, and have changed and shaped the land, the wild plants and animals, the crops and the constructions and buildings on it. All that speaks of the past and the traditions of the Islands, of the natural world too, is heritage.’ Haslam, S. M. & Borg, J., 2002. ‘Let’s Go and Look After our Nature, our Heritage!’. Ministry of Agriculture & Fisheries - Socjeta Agraria, Malta. The Island of Gozo Location: Gozo (Għawdex) is the second largest island of the Maltese Archipelago. The archipelago consists of the Islands of Malta, Gozo and Comino as well as a few other uninhabited islets. It is roughly situated in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, about 93km south of Sicily, 350 kilometres due north of Tripoli and about 290 km from the nearest point on the North African mainland. Size: The total surface area of the Islands amounts to 315.6 square kilometres and are among the smallest inhabited islands in the Mediterranean. With a coastline of 47 km, Gozo occupies an area of 66 square kilometres and is 14 km at its longest and 7 km at its widest. IRMCo, Malta e-Module Gozo Unit 1 Page 1/8 Climate: The prevailing climate in the Maltese Islands is typically Mediterranean, with a mild, wet winter and a long, dry summer. -

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 189 October 2017 1

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 189 October 2017 1 MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 189 October 2017 By POLITICO The Malta and European Union flags around the Auberge de Castille in Valletta | EPA/Domenic Aquilina For Malta, the EU’s smallest country with a population of around 420,000, its first shot at the rotating presidency of the Council of the EU was pitched as the island’s coming-out ceremony. For smaller member countries, the presidency is as an extended advertising campaign, giving airtime to a country normally barely on the radar of the world’s media. But with potential calamity never far from the door in the form of Brexit, the migration crisis and other problems, the presidency also has a vital diplomatic role — brokering agreement among 28 nations with often wildly differing agendas. At times, cat-herding looks like a vastly simpler profession. Tasked with leading discussions between EU governments as well as negotiating draft laws with the European Parliament, the role is at the centre of what Brussels does best: legislating. (Or at least attempting to.) And Malta turned out to be rather good at it — negotiating deals to push through legislation in dozens of policy areas. Prime Minister Joseph Muscat, who once led opposition to EU membership in the island’s 2003 referendum, described the opportunity as “fantastic” when POLITICO interviewed him earlier this year. He and his ministers took full advantage of the many press conferences that placed them alongside EU’s political elite, who were gushing in their praise of Muscat at the closing Council summit last week. -

Malta & Gozo Directions

DIRECTIONS Malta & Gozo Up-to-date DIRECTIONS Inspired IDEAS User-friendly MAPS A ROUGH GUIDES SERIES Malta & Gozo DIRECTIONS WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY Victor Paul Borg NEW YORK • LONDON • DELHI www.roughguides.com 2 Tips for reading this e-book Your e-book Reader has many options for viewing and navigating through an e-book. Explore the dropdown menus and toolbar at the top and the status bar at the bottom of the display window to familiarize yourself with these. The following guidelines are provided to assist users who are not familiar with PDF files. For a complete user guide, see the Help menu of your Reader. • You can read the pages in this e-book one at a time, or as two pages facing each other, as in a regular book. To select how you’d like to view the pages, click on the View menu on the top panel and choose the Single Page, Continuous, Facing or Continuous – Facing option. • You can scroll through the pages or use the arrows at the top or bottom of the display window to turn pages. You can also type a page number into the status bar at the bottom and be taken directly there. Or else use the arrows or the PageUp and PageDown keys on your keyboard. • You can view thumbnail images of all the pages by clicking on the Thumbnail tab on the left. Clicking on the thumbnail of a particular page will take you there. • You can use the Zoom In and Zoom Out tools (magnifying glass) to magnify or reduce the print size: click on the tool, then enclose what you want to magnify or reduce in a rectangle. -

PDF Compressor Pro PDF Compressor Pro

PDF Compressor Pro PDF Compressor Pro Joseph Bezzina Ten singular stories from the village of Santa Luċija • Gozo with input by Ricky Bugeja – Kelly Cassar – Gordon Formosa – Graziella Grech – Rodienne Grech – Joe Mizzi – Mario Mizzi – Lucienne Sultana – Marilyn Sultana Cover picture: Aimee Grech Designs (monochrome): Luke Azzopardi Designs (colour): Aimee Grech Photos: Joseph Bezzina – Paul Camilleri – Joe Mizzi Santa Luċija–Gozo FONDAZZJONI FOLKLORISTIA TA’ KLULA 2011 PDF Compressor Pro First published in 2011 by the FONDAZZJONI FOLKLORISTIA TA’ KLULA 23 Triq Ta’ Klula, Santa Luċija, Gozo. kcm 3060. Malta. and eco-gozo © Joseph Bezzina • 2011 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmited in any form or by any means, known or yet to be invented, for any purpose whatsoever, without the writen permission of the author and that of the Fondazzjoni Folkloristika Ta’ Klula which permission must be obtained beforehand. Cataloguing in Publication Data Bezzina, Joseph, 1950- Ten singular stories from Santa Luċija, Gozo / Joseph Bezzina with input by Ricky Bugeja – Kelly Cassar – Gordon Formosa – Graziella Grech – Rodienne Grech – Joe Mizzi – Mario Mizzi – Lucienne Sultana – Marilyn Sultana. – Santa Luċija, Gozo : Fondazzjoni Folkloristika Ta’ Klula – Eco Gozo, 2011 40 p. : col. ill. ; 18 cm. 1. Santa Luċija (Gozo) – History 2. Santa Luċija (Gozo) – Churches 3. Churches – Gozo, Malta I. Title DDC: 945.8573 LC: DG999.N336C358B4 Melitensia Classiication: MZ8 SLC Computer seting in font Arno Pro Production Joseph Bezzina Printed and bound in Malta Gozo Press, Għajnsielem-Gozo. GSM 9016 PDF Compressor Pro contents 1 he spring at Għajn Għabdun . -

Malta Libraries Annual Report 2015 / Malta Libraries

Annual Report 2015 One of the 800 engraved plates from the Hortus Romanus of which eight volumes were published in between 1772 and 1793. National Library of Malta ii | Annual Report 2015 ANNUAL REPORT 2015 iii | Annual Report 2015 Cataloguing-in-Publication Data______________________________________ Malta Libraries Annual report 2015 / Malta Libraries. – Valletta : Malta Libraries, 2016. vi, 46 p. : col. ill., charts ; 30 cm. 1. Malta Libraries 2. Libraries – Malta – Statistics 3. National libraries – Malta – Statistics 4. Public libraries – Malta – Statistics I. Title ISBN 9789995789701 (e-book) ISBN 9789995781491 (print) DDC 23: 027.04585 Copyright © 2016 Malta Libraries. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the copyright holders. iv | Annual Report 2015 Contents Foreword 1 Functions 3 The National Library of Malta 5 Mission Statement 5 Reader Services 5 Collections Management 12 Digitisation Unit 12 Preservation and Conservation 13 Restoration Unit and Bindery 13 National Bibliographic Office 15 Legal Deposit 16 Acquisitions 16 Outreach Programmes 17 Exhibitions 17 Publications and Book Launches 21 Public Lectures 22 Participation in other Exhibitions 24 Educational and Cultural Events 25 The Public Library Network 31 Mission Statement 31 Outreach Services for Public Libraries 31 Internships and Voluntary Work 36 Reader Services 37 Audiovisual Library 40 Reference Services 41 Talking Books Section 41 Other Public Libraries’ Developments 42 v | Annual Report 2015 Acquisitions 42 Cataloguing and Classification Section 42 Collections Development 43 Information and Communication Technology Support Unit (ICTSU) 43 Financial Statements 46 vi | Annual Report 2015 Foreword It was a remarkable year for Malta Libraries. -

Ancient Anchors from Malta and Gozo Elaine Azzopardi, Timmy Gambin, Renata Zerafa

Elaine Azzopardi, Timmy Gambin, Renata Zerafa Ancient anchors from Malta and Gozo Elaine Azzopardi, Timmy Gambin, Renata Zerafa In 2011, the national archaeological collection managed by Heritage Malta included 24 lead anchor stocks. They are the remains of ancient wooden anchors used on boats that sheltered in the harbours and bays of the Maltese Islands. This paper includes a gazetteer documenting these stocks with the aim of highlighting their value to maritime archaeology and to create a tool that will facilitate further study. Anchors form part of the basic equipment of seagoing and the placing of these in a broader context will help vessels. Although they are used to ‘attach’ a vessel to further our knowledge of the maritime activity within the seabed, an anchored boat is not stationary as it an area. moves with the wind and currents. Anchors can also When undertaking such a study it is important be deployed whilst underway to increase stability and to keep the following in mind: manoeuvrability in bad weather. Furthermore, their 1) There is a correlation between the popularity of use as votive offerings (Frost 2001) and inscriptions of dive sites and the discovery of anchor stocks. names of deities on stocks highlight their importance 2) Although many stocks were given to heritage to ancient seafarers. authorities others were kept or melted down One cannot be sure how many anchors ships to produce diving weights. This distorts the carried. Numbers found differ from site to site. For picture of quantification and distribution. example, the second millennium BC Ulu Burun 3) Sedimentation in many Maltese bays has shipwreck was carrying 24 stone anchors but it is not buried archaeological layers. -

Currency in Malta )

CURRENCY IN MALTA ) Joseph C. Sammut CENTRAL BANK OF MALTA 2001 CONTENTS List of Plates ........................ ......................... ......... ............................................ .... ... XllI List of Illustrated Documents ............ ,...................................................................... XVll Foreword .................................................................................................................. XIX } Preface...................................................................................................................... XXI Author's Introduction............................................................................................... XXllI I THE COINAGE OF MALTA The Earliest Coins found in Malta.................................................................... 1 Maltese Coins of the Roman Period................................................................. 2 Roman Coinage ................................................................................................ 5 Vandalic, Ostrogothic and Byzantine Coins ........... ............ ............ ............ ...... 7 Muslim Coinage ............................................................................................... 8 Medieval Currency ........................................................................................... 9 The Coinage of the Order of St John in Malta (1530-1798) ............................ 34 The Mint of the Order...................................................................................... -

Mill‑PARLAMENT

Nr 12 Marzu 2016 March 2016 PARLAMENT TA’ MALTA mill‑PARLAMENT Perjodiku maħruġ mill‑Uffiċċju tal‑Ispeaker Periodical issued by the Office of the Speaker mill-PARLAMENT - Marzu 2016 Mistiedna jżuru l-wirja fotografika Women‘ Refugees Guests visit the photgraphic exhibition ‘Women and Asylum Seekers’ li ġiet imtella’ fil-foyer tal- Refugees and Asylum Seekers’ which was organised in Parlament fil-bidu ta’ Marzu. the Parliament’s foyer in the beginning of May. Ħarġa Nru 12/Issue No. 12 3Daħla Marzu 2016/March 2016 Foreword Ippubblikat mill‑Uffiċċju tal‑Ispeaker 4 Xi Ġurnali F’Malta Mill-1798 sal-1964 Published by the Office of the Speaker Some Newspapers In Malta From 1798 to 1964 Bord Editorjali Editorial Board 10L-Uffiċċju Nazzjonali Tal-Verifika - L-Għassies Tal-Fondi Pubbliċi Ray Scicluna Josanne Paris National Audit Office – The Guardian Of The Public Purse Ancel Farrugia Migneco Eleanor Scerri 18Attivitajiet tal-Parlament Sarah Gauci Activities in Parliament Eric Frendo Indirizz Postali 34Attivitajiet Internazzjonali Postal Address International Activities House of Representatives Republic Street Valletta VLT 1115 Malta +356 2559 6000 Qoxra: Sessjoni speċjali fil-Kamra li mmarkat Jum il-Commonwealth www.parlament.mt Cover: Special session in the House [email protected] to mark Commonwealth Day. ISSN 2308‑538X ISSN (online) 2308‑6637 Ritratti/Photos: Parlament ta’ Malta/DOI 2 mill-PARLAMENT - Marzu 2016 Daħla Foreword F’din it‑12‑il ħarġa tal‑pubblikazzjoni mill‑Parlament insibu In this 12th issue of the publication mill‑Parlament one diversi artikli interessanti. Artiklu ferm interessanti huwa can find several interesting articles. One of these is the dak ta’ Dr. -

For Morale Or Propaganda? the Newspapers of Bonaparte

The Genesis of Napoleonic Propaganda: Chapter 3 4/25/03 10:55 AM Chapter 3: For Morale or Propaganda? The Newspapers of Bonaparte A Need For His Own Press 1 While Napoleon Bonaparte's propaganda strategies to present himself in the image of the revolutionary hero seemed effective for the majority of the French public, not everyone was taken in. As Jeremy Popkin notes in his The Right-Wing Press in France, 1792—1800, many right-wing journalists warned of the Corsican general's unbridled ambition, some as early as October 1795 when Napoleon fired his famous "whiff of grapeshot" in defense of the Directory. 1 In March 1796, even before the Italian campaign had really begun, the editor of the Messager du Soir likewise called attention to Bonaparte's ambitions, and once the Italian army had embarked on its successful campaign, right-wing papers continued to issue caveats about the successful 2 general. By the spring of 1797, these attacks had intensified, leading Bonaparte, through his lieutenant General Augereau, to petition the government for relief from the virulent attacks of "certain journalists" in the form of censorship. 3 Despite the government's public expressions of satisfaction with Bonaparte's military and political actions in Italy, however, the attacks of the right-wing press did not slow. 4 In June, La Censure compared Bonaparte to the Grand Turk and accused him of placing himself above the Directory. 5 In July, the editor of the royalist L'Invariable wrote concerning the Army of Italy and its commanding general: "Does it remain a French army? The conduct of Buonaparte seems to answer in the negative .. -

Maltese Journalism 1838-1992

'i""'::::)~/M' "/~j(: ,;"';"~~'M\':'E"\~FJ~'i'\S"E' "f, ,;::\" "~?~" ",} " '~',"J' ",' "'O"U'R''""", H' ::N~ " AL'IJ'SM"','" ""'" """" , 1, 1838 .. 1992 An Historical Overview Henry Frendo f.~,· [ Press Club Publications (Malta) MALTESE JOURNALISM' 1838-1992 " , An Historical Overview Henry Frendo • • Sponsored by 'elemalta corporation Press Club Publications (Malta) PRESS CLUB (MALTA) PUBLICATIONS No. 1 © Henry Frendo 1994 " .. First published 1994 Published by Press Club (Malta), P.O. Box 412, Valletta, Malta Cover design and layout by Joseph A. Cachia .. Printed by Agius Printing Press, Floriana, Malta • Cataloging in publication data Frendo Henry, 1948- Maltese journalism, 1838-1992: an historical overview / Henry Frendo. - Valletta : Press Club Publications, 1994 xii, 130 p. : ill. ; 22cm. (Press Club (Malta) publications; no. 1) 1. Journalism - Malta - History 2. Newspapers - Malta I. Title n. Series Contents Foreword Author's preface 1 - Shades of the Printed Word ...................................................................... .1 2 - Censorship Abolished ................................................................................. 8 3 - The Making of Public Opinion ................................................................ 17 4 - Deus et Lux ..............................................................................................26 5 - Present and Future .................................................................................. 34 .. Appendices ....................................................................................................43