John SC Abbott and Self-Interested Motherhood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Becoming a Mother Is Nothing Like You See on TV!”: a Reflexive Autoethnography Exploring Dominant Cultural Ideologies of Motherhood

MORAN, EMILY JEAN, Ph.D. “Becoming a Mother is Nothing Like You See on TV!”: A Reflexive Autoethnography Exploring Dominant Cultural Ideologies of Motherhood. (2014) Directed by Dr. Leila E. Villaverde. 348 pp. Mothers in contemporary American society are bombarded with images and stereotypes about motherhood. Dominant cultural discourses of motherhood draw from essentialist and socially constructed ideologies that are oppressive to women. This study uses autoethnographic research methods to explore the author’s experiences becoming a mother. Feminist theory is utilized to analyze the themes, the silences, and the absences in the autoethnographic stories. Using a feminist theoretical lens allows the author to deconstruct the hegemonic ideologies that shape the experience becoming a mother. I examine the role of dominant ideologies of motherhood in my own life. I explore the practices of maternal gatekeeping paying particular attention to the role of attachment theory in shaping the ideology of intensive mothering. I argue that autoethnography as a research method allows writers and readers to cross borders so long as they practice deep reflexivity and allow themselves to be vulnerable. This research is similar to Van Maanen’s (1988) confessional tale, where the researcher writes about the process that takes place behind the scenes of the research project. In this project, I write an autoethnography and then I describe the process of analysis, vulnerability, and reflexivity while examining the themes and silences within the data. “BECOMING A MOTHER IS NOTHING LIKE YOU SEE ON TV!”: A REFLEXIVE AUTOETHNOGRAPHY EXPLORING DOMINANT CULTURAL IDEOLOGIES OF MOTHERHOOD by Emily Jean Moran A Dissertation Submitted to the the Faculty of The Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Greensboro 2014 Approved by Leila E. -

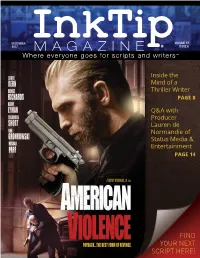

MAGAZINE ® ISSUE 6 Where Everyone Goes for Scripts and Writers™

DECEMBER VOLUME 17 2017 MAGAZINE ® ISSUE 6 Where everyone goes for scripts and writers™ Inside the Mind of a Thriller Writer PAGE 8 Q&A with Producer Lauren de Normandie of Status Media & Entertainment PAGE 14 FIND YOUR NEXT SCRIPT HERE! CONTENTS Contest/Festival Winners 4 Feature Scripts – FIND YOUR Grouped by Genre SCRIPTS FAST 5 ON INKTIP! Inside the Mind of a Thriller Writer 8 INKTIP OFFERS: Q&A with Producer Lauren • Listings of Scripts and Writers Updated Daily de Normandie of Status Media • Mandates Catered to Your Needs & Entertainment • Newsletters of the Latest Scripts and Writers 14 • Personalized Customer Service • Comprehensive Film Commissions Directory Scripts Represented by Agents/Managers 40 Teleplays 43 You will find what you need on InkTip Sign up at InkTip.com! Or call 818-951-8811. Note: For your protection, writers are required to sign a comprehensive release form before they place their scripts on our site. 3 WHAT PEOPLE SAY ABOUT INKTIP WRITERS “[InkTip] was the resource that connected “Without InkTip, I wouldn’t be a produced a director/producer with my screenplay screenwriter. I’d like to think I’d have – and quite quickly. I HAVE BEEN gotten there eventually, but INKTIP ABSOLUTELY DELIGHTED CERTAINLY MADE IT HAPPEN WITH THE SUPPORT AND FASTER … InkTip puts screenwriters into OPPORTUNITIES I’ve gotten through contact with working producers.” being associated with InkTip.” – ANN KIMBROUGH, GOOD KID/BAD KID – DENNIS BUSH, LOVE OR WHATEVER “InkTip gave me the access that I needed “There is nobody out there doing more to directors that I BELIEVE ARE for writers than InkTip – nobody. -

Motherhood in Science – How Children Change Our Academic Careers

October 2020 Motherhood in Science – How children change our academic careers Experiences shared by the GYA Women in Science Working Group Nova Ahmed, Amal Amin, Shalini S. Arya, Mary Donnabelle Balela, Ghada Bassioni, Flavia Ferreira Pires, Ana M. González Ramos, Mimi Haryani Hassim, Roula Inglesi-Lotz, Mari-Vaughn V. Johnson, Sandeep Kaur-Ghumaan, Rym Kefi-Ben Atig, Seda Keskin, Sandra López-Vergès, Vanny Narita, Camila Ortolan Cervone, Milica Pešic, Anina Rich, Özge Yaka, Karin Carmit Yefet, Meron Zeleke Eresso Motherhood in Science Motherhood in Science Table of Contents Preface The modern scientist’s journey towards excellence is multidimensional and requires skills in balancing all the responsibilities consistently and in a timely Preface 3 manner. Even though progress has been achieved in recent times, when the Chapter 1: Introductory thoughts 5 academic is a “mother”, the roles toggle with different priorities involving ca- Section 1: Setting the scene of motherhood in science nowadays 8 reer, family and more. A professional mother working towards a deadline may Chapter 2: Why do we translate family and employment as competitive spheres? 8 change her role to a full-time mother once her child needs exclusive attention. Chapter 3: The “Problem that Has No Name”: giving voice to invisible Mothers-to-Be The experience of motherhood is challenging yet humbling as shared by eight- in academia 16 Chapter 4: Motherhood and science – who knew? 24 een women from the Women in Science Working Group of the Global Young Academy in this publication. Section 2: Balancing science and motherhood 29 Chapter 5: Motherhood: a journey of surprises 29 The decision of a woman to become a mother is rooted in a range of reasons Chapter 6: Following a schedule 32 Chapter 7: Motivation, persistence and harmony 35 – genetic, cultural, harmonic, societal, and others. -

The Implicit Costs of Motherhood Over the Lifecycle: Cross-Cohort Evidence from Administrative Longitudinal Data

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 10558 The Implicit Costs of Motherhood over the Lifecycle: Cross-Cohort Evidence from Administrative Longitudinal Data Christian Neumeier Todd Sørensen Douglas Webber FEBRUARY 2017 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 10558 The Implicit Costs of Motherhood over the Lifecycle: Cross-Cohort Evidence from Administrative Longitudinal Data Christian Neumeier University of Konstanz Todd Sørensen University of Nevada, Reno and IZA Douglas Webber Temple University and IZA FEBRUARY 2017 Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but IZA takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The IZA Institute of Labor Economics is an independent economic research institute that conducts research in labor economics and offers evidence-based policy advice on labor market issues. Supported by the Deutsche Post Foundation, IZA runs the world’s largest network of economists, whose research aims to provide answers to the global labor market challenges of our time. Our key objective is to build bridges between academic research, policymakers and society. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Schaumburg-Lippe-Straße 5–9 Phone: +49-228-3894-0 53113 Bonn, Germany Email: [email protected] www.iza.org IZA DP No. 10558 FEBRUARY 2017 ABSTRACT The Implicit Costs of Motherhood over the Lifecycle: Cross-Cohort Evidence from Administrative Longitudinal Data* The explicit costs of raising a child have grown over the past several decades. -

The Real Story Behind Millennials and the New Localism

LOCALISM IN AMERICA Why We Should Tackle Our Big Challenges at the Local Level Localism in America WHY WE SHOULD TACKLE OUR BIG CHALLENGES AT THE LOCAL LEVEL FEBRUARY 2018 SAMUEL J. ABRAMS FREDERICK M. HESS JAY AIYER HOWARD HUSOCK KARLYN BOWMAN ANDREW P. JOHNSON WENDELL COX LEO LINBECK III ROBERT DOAR THOMAS P. MILLER RICHARD FLORIDA ELEANOR O’NEIL TORY GATTIS DOUG ROSS NATALIE GOCHNOUR ANDY SMARICK MICHAEL D. HAIS ANNE SNYDER JOHN HATFIELD MORLEY WINOGRAD EDITED BY JOEL KOTKIN AND RYAN STREETER © 2018 by the American Enterprise Institute. All rights reserved. The American Enterprise Institute (AEI) is a nonpartisan, nonprofit, 501(c)(3) educational organization and does not take institutional positions on any issues. The views expressed here are those of the author(s). Millocalists? The Real Story Behind Millennials and the New Localism Anne Snyder ocalism is more than a political movement. For But what you sense in these farmers markets is L many, particularly millennials, it also expresses an expression of a generation that, contrary to car- deep-seated cultural values that appeal to their aspi- icature, longs for a sense of empowered contribu- rations and hungers. But, insofar as politics reflects tion, meaningful community, and yes, sacrifice, too. deeper forces twitching in the social fabric—this last The upper tier of millennials—those between ages 26 election was no less emblematic, as it sent shock and 34—graduated to the tune of “Save the World!” waves through the elite power centers—more and only to find themselves starved for a sense of tangible more young people are choosing to live at a scale they impact in the spheres they can more immediately see can see and touch, grounded in a place and committed and touch. -

On the Margins of Motherhood: Choosing to Be Child-Free in Lucie Joubert’S L’Envers Du Landau (2010)

Women: A Cultural Review ISSN: 0957-4042 (Print) 1470-1367 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rwcr20 On the Margins of Motherhood: Choosing to Be Child-Free in Lucie Joubert’s L’Envers du landau (2010) Julie Rodgers To cite this article: Julie Rodgers (2018) On the Margins of Motherhood: Choosing to Be Child- Free in Lucie Joubert’s L’Enversdulandau (2010), Women: A Cultural Review, 29:1, 75-96, DOI: 10.1080/09574042.2018.1425537 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/09574042.2018.1425537 Published online: 29 Mar 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 149 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 1 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rwcr20 w .................JULIE.............. RODGERS..................................................... On the Margins of Motherhood: Choosing to Be Child-Free in Lucie Joubert’ s L ’ Envers du landau (2010) Abstract: Voluntarily choosing not to have children is increasingly becoming a preferred life option in contemporary society. Yet there remains an inherent suspicion and pitying of women who do not follow what is still perceived, despite several waves of feminism, as their biological destiny. Such choices are considered ‘unspeakable’ by the dominant pro- natalist discourse that currently presides in western advanced-capitalist society. This article attempts to challenge and reverse prescribed beliefs about motherhood and create a textual space for those who have been denigrated for choosing not to become mothers. Keywords: French Canadian literature, Lucie Joubert, motherhood, pro-natalism, voluntary childlessness Despite the many gains of second-wave feminism over the course of the twentieth century and its endeavour to decentre motherhood from the core of the female existence, it would appear that voluntarily choosing not to become a mother is a decision with which society is uncomfortable and, moreover, refuses outright to accept as valid. -

Postpartum Depression and the Xnedlcallcatlon of Motherhood: a Comparison of Lay and Professional Views

Order Number 010B195 Postpartum depression and the xnedlcallcatlon of motherhood: A comparison of lay and professional views Ransdell, Lisa Lynn, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1990 Copyright ©1990 by RansdeU, IdeeLynn. All rights reserved. U-M-I 300 N. Zceb Rd. A nn A ibor, M I 48106 NOTE TO USERS THE ORIGINAL DOCUMENT RECEIVED BY U.M.I. CONTAINED PAGES WITH POOR PRINT. PAGES WERE FILMED AS RECEIVED. THIS REPRODUCTION IS THE BEST AVAILABLE COPY. POSTPARTUM DEPRESSION AND THE MEDI CALI 2ATI ON OF MOTHERHOOD* A COMPARISON OF LAY AND PROFESSIONAL VIEWS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Lisa L. Ransdell, B.A., M.A. ***** The Ohio S tate U n iv e rsity 1990 Dissertation Committee: Approved By Verta Taylor Katherine Meyer Joan Huber Adv i ser Department of Sociology Le i 1 a Rupp Virginia Richardson Copyright by Lis* L. R*n*d*l1 1990 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost I owe a debt of gratitude to my adviser, Dr. Varta Taylor. Her patiant criticisms and partinant insights guidad ma through tha dissartation procass and inspirad ma throughout my graduate school caraar. Additionally I am grataful to har for inviting ma in 1984 to work on tha rasaarch projact which lad to tha dissartat ion. It was a parfact blending of my interests in sociology and my cammitments as a feminist, and tha mix will keep ma interested in this topic for a long time to coma. Second, I am grateful to tha members of my d issa rtatio n committee, Katharine Mayer, Joan Huber, L eila Rupp, and Virginia Richardson. -

The Demon Haunted World

THE DEMON- HAUNTED WORLD Science as a Candle in the Dark CARL SAGAN BALLANTINE BOOKS • NEW YORK Preface MY TEACHERS It was a blustery fall day in 1939. In the streets outside the apartment building, fallen leaves were swirling in little whirlwinds, each with a life of its own. It was good to be inside and warm and safe, with my mother preparing dinner in the next room. In our apartment there were no older kids who picked on you for no reason. Just the week be- fore, I had been in a fight—I can't remember, after all these years, who it was with; maybe it was Snoony Agata from the third floor— and, after a wild swing, I found I had put my fist through the plate glass window of Schechter's drug store. Mr. Schechter was solicitous: "It's all right, I'm insured," he said as he put some unbelievably painful antiseptic on my wrist. My mother took me to the doctor whose office was on the ground floor of our building. With a pair of tweezers, he pulled out a fragment of glass. Using needle and thread, he sewed two stitches. "Two stitches!" my father had repeated later that night. He knew about stitches, because he was a cutter in the garment industry; his job was to use a very scary power saw to cut out patterns—backs, say, or sleeves for ladies' coats and suits—from an enormous stack of cloth. Then the patterns were conveyed to endless rows of women sitting at sewing machines. -

Sleep, Sickness, and Spirituality: Altered States and Victorian Visions of Femininity in British and American Art, 1850-1915

Sleep, Sickness, and Spirituality: Altered States and Victorian Visions of Femininity in British and American Art, 1850-1915 Kimberly E. Hereford A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: Susan Casteras, Chair Paul Berger Stuart Lingo Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art History ©Copyright 2015 Kimberly E. Hereford ii University of Washington Abstract Sleep, Sickness, and Spirituality: Altered States and Victorian Visions of Femininity in British and American Art, 1850-1915 Kimberly E. Hereford Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Susan Casteras Art History This dissertation examines representations in art of the Victorian woman in “altered states.” Though characterized in Victorian art in a number of ways, women are most commonly stereotyped as physically listless and mentally vacuous. The images examined show the Victorian female in a languid and at times reclining or supine pose in these representations. In addition, her demeanor implies both emotional and physical depletion, and there is both a pronounced abandonment of the physical and a collapsing effect, as if all mental faculties are withdrawing inward. Each chapter is dedicated to examining one of these distinct but interrelated types of femininity that flourished throughout British and American art from c. 1850 to c. 1910. The chapters for this dissertation are organized sequentially to demonstrate a selected progression of various states of consciousness, from the most obvious (the sleeping woman) to iii the more nuanced (the female Aesthete and the female medium). In each chapter, there is the visual perception of the Victorian woman as having access to otherworldly conditions of one form or another. -

The Art of the Final Judgment Artists Have Struggled to Portray the Final Judgment in a Spiritu- Ally Discerning Manner

The Art of the Final Judgment Artists have struggled to portray the Final Judgment in a spiritu- ally discerning manner. How can their work avoid sinking into a kind of morbid voyeurism and superficial speculation about future calamities? Christian Reflection Prayer A Series in Faith and Ethics Scripture Reading: 1 Thessalonians 4:13-18; 1 Corinthians 15:50-57; Matthew 24:29-31; Revelation 1:4-8 Responsive Reading† Come, you sinners poor and needy, Focus Articles: weak and wounded, sick and sore: Jesus ready stands to save us, Left Behind and Getting full of pity, love and power. Ahead Come, you thirsty, come and welcome, (Heaven and Hell, pp. 70- God’s free bounty glorify; 78) True belief and true repentance, Confronted every grace that brings us nigh. (Heaven and Hell, pp. 46- Come you weary, heavy-laden, 49) lost and ruined by the fall; Falling If we tarry, ‘til we better, (Heaven and Hell, pp. 50- we will never come at all. 52) Let not conscience make you linger, nor of fitness fondly dream; All the fitness God requires is to feel our own great need. Reflection Vivid scriptural images have inspired “high,” “folk,” and popular artists to represent God’s final judgment—not merely to illus- trate the biblical words, but through their artwork to teach, preach, and prophetically lead the church. As Christians we are to “discern the spirits,” or to weigh their work for the body of What do you think? Christ, as Paul teaches (1 Corinthians 12:10; 14:29). We might ask: Was this study guide useful Does the art express biblical ideas in a faithful and theologically for your personal or group sensitive way? How does it integrate non-biblical materials? study? Please send your What message does the art convey in the contexts in which it suggestions to: typically is used? [email protected] In Michelangelo’s Last Judgment, the action flows in an arching movement: dead persons are led from their graves, taken up- wards to Christ’s judgment, and (when judged unrighteous) sent down to hell. -

The World's First Love

The World's First Love By FULTON J. SHEEN, PH.D., D.D. Agregé in Philosophy from the University of Louvain Auxiliary Bishop of New York National Director, World Mission Society for the Propagation of the Faith McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc. New York - London - Toronto Copyright, 1952, by Fulton J. Sheen. Etext edited by Darrell Wright, 2009, from a text file at archive.org DEDICATED TO THE WOMAN I LOVE The Woman Whom even God dreamed of Before the world was made; The Woman of Whom I was born At cost of pain and labor at a Cross; The Woman Who, though no priest, Could yet on Calvary's Hill breathe: "This is my Body; This is my Blood" For none save her gave Him human life. The Woman Who guides my pen, Which falters so with words In telling of the Word. The Woman Who, in a world of Reds, Shows forth the blue of hope. Accept these dried grapes of thoughts From this poor author, who has no wine; And with Cana's magic and thy Son's Power Work a miracle and save a soul - Forgetting not my own. Contents PART I: THE WOMAN THE WORLD LOVES 1 Love Begins with a Dream 3 2 When Freedom and Love Were One: The Annunciation 14 3 The Song of the Woman: The Visitation 28 4 When Did Belief in the Virgin Birth Begin? 45 5 All Mothers Are Alike Save One 58 6 The Virgin Mother 75 7 The World's Happiest Marriage 86 8 Obedience and Love 96 9 The Marriage Feast at Cana 112 10 Love and Sorrow 121 11 The Assumption and the Modern World 132 PART II: THE WORLD THE WOMAN LOVES 12 Man and Woman 147 13 The Seven Laws of Love 160 14 Virginity and Love 167 15 Equity and Equality 175 16 The Madonna of the World 186 17 Mary and the Moslems 204 18 Roses and Prayers 210 19 The Fifteen Mysteries of the Rosary 221 20 Misery of Soul and the Queen of Mercy 228 21 Mary and the Sword 243 22 The Woman and the Atom 275 PART I The Woman the World Loves CHAPTER 1 Love Begins with a Dream [3] Every person carries within his heart a blueprint of the one he loves. -

View in Pages

news friendsofeps.org spring 2020 issue in this issue... our stories meeting the needs of our clients during uncertain times celebrating motherhood “ALL THAT I AM OR EVER HOPE TO BE, I OWE TO MY ANGEL MOTHER." ABRAHAM LINCOLN others are a true gift from God! With Mother’s Day approaching, this spring Mnewsletter is dedicated to moms - especially the beautiful mothers EPS serves every day, even amidst the pandemic. COVID-19 is presenting new and unique challenges in our service delivery, and we’re finding solutions because vulnerable women who are pregnant and in crisis need us now more than ever! The EPS staff is working tirelessly to adjust and respond to the growing levels of anxiety among our clients. In addition to the threat of the virus, abortion advocates are working to expand chemical abortion access through telemedicine to accommodate stay-at-home orders. It is critical for EPS to address these issues head on and to reach as many women as we can when they first learn they are pregnant. EPS is the life-affirming, compassionate, and loving alternative to abortion. And our Maple Village center – located next door to an abortion provider – is perfectly positioned for this battle for life. As you read this newsletter, please prayerfully consider ways to partner with us this month as we address both the abortion and COVID-19 crises. Your partnership inspires us and makes it possible for staff to keep operating on the front lines. We appreciate your generosity, and hold you close in our prayers. Best, LAURA BUDDENBERG, MS Executive Director at a glance finding solutions during a pandemic MEDICAL SERVICES || Abortions are still happening in EPS BOUTIQUE || While the EPS boutique is temporarily Nebraska despite COVID-19.