The Culture of Post-Narcissism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

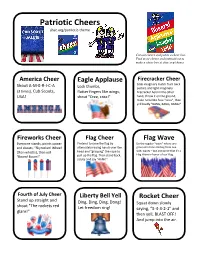

Patriotic Cheers Shac.Org/Patriotic-Theme

Patriotic Cheers shac.org/patriotic-theme Cut out cheers and put in a cheer box. Find more cheers and instructions to make a cheer box at shac.org/cheers. America Cheer Eagle Applause Firecracker Cheer Shout A-M-E-R-I-C-A Grab imaginary match from back Lock thumbs, pocket, and light imaginary (3 times), Cub Scouts, flutter fingers like wings, firecracker held in the other USA! shout "Cree, cree!" hand, throw it on the ground, make noise like fuse "sssss", then yell loudly "BANG, BANG, BANG!" Fireworks Cheer Flag Cheer Flag Wave Everyone stands, points upward Pretend to raise the flag by Do the regular “wave” where one and shouts, “Skyrocket! Whee!” alternately raising hands over the group at a time starting from one (then whistle), then yell head and “grasping” the rope to side, waves – but announce that it’s a Flag Wave in honor of our Flag. “Boom! Boom!” pull up the flag. Then stand back, salute and say “Ahhh!” Fourth of July Cheer Liberty Bell Yell Rocket Cheer Stand up straight and Ding, Ding, Ding, Dong! Squat down slowly shout "The rockets red Let freedom ring! saying, “5-4-3-2-1” and glare!" then yell, BLAST OFF! And jump into the air. Patriotic Cheer Mount New Citizen Cheer To recognize the hard work of Shout “U.S.A!” and thrust hand learning in order to pass the test with doubled up fist skyward Rushmore Cheer to become a new citizen, have while shouting “Hooray for the Washington, Jefferson, everyone stand, make a salute, Red, White and Blue!” Lincoln, Roosevelt! and say “We salute you!” Soldier Cheer Statue of Liberty USA-BSA Cheer Stand at attention and Cheer One group yells, “USA!” The salute. -

Junior Friends Groton Public Library

JUNIOR FRIENDS GROTON PUBLIC LIBRARY 52 Newtown Road Groton, CT 06340 860.441.6750 [email protected] grotonpl.org Who We Are How to be a Friend Join Today The Junior Friends of the Groton Becoming a member of the Junior Public Library is a group of young to the Library Friends is easy! Complete the form people who organize service projects Show Respect — take good care of below, detach and return it to the and fundraisers that benefit the the books, computers and toys in Groton Public Library. Library and the community. the Library Once you become a Junior Friend, Becoming a Junior Friend is a great Keep It Down — use a quiet voice in you will receive a membership card way to show your appreciation for the the Library and regular emails listing Junior Library and give something back to Say Thanks — show your Friends’ meetings and events. the community. appreciation for the Library staff and volunteers Name What We Do Spread the Word — tell your friends that the Groton Public Address The Junior Friends actively support Library is a great place to visit the Library through volunteering, fundraising and sponsoring events that involve and inspire young people. The Junior Friends: City / State / Zip Code Help clean and decorate the Library and outside play area Sponsor fundraisers that support Phone the purchase of supplies and special events Host movie and craft programs Email Take on projects that benefit charitable groups within the I give the Groton Public Library, its community r e p resentatives and employees permission to take photographs or videos of me at Junior Friends Events. -

About to Launch Its Iinal Season, but Kristin Davis Isnt About to Retire Anytirne Sooll

5*: -lirrJ ;n* {lri.,r is abouT To launch its iinal season, but KrisTin Davis isnt about to retire anytirne sooll. By Bill Cloviil ?hotograph by clill ?eters ../ I I I ristin Davis is standing in the rniddle of a sma11, Upper\\Iest I t Si,Je caf6 looking for her lunch date. Ir isr't until we make *e | \_. contact that I realize that this is indeed the 38-year-oJ.1 actress of Sir rmd th Ctt1, fame. In jeans with her hair pulled back, she looks more like rlv daughter's cheedea.ling coach than Charlotte, the charactcr she plays on the HBO show; recent In Styb rnagazine cover gidi or olre of E Channel's Most Eligible Hollywood Bachelorettes. Later. I'11 rhink back to what Davis's Mason Gross theater buddy Paula Goldberg (GMGSAB9) told me on the prhone from L.A.: "There ;'rre a lot of beautiful and talented rvollen out there, but what separated Kristin was her incr:edible drive ;rnd inner confidence. She wasnt going to let anyone or anvthing cleter her fi'orn her dream. I wish I could say the samc for mysclf." Davis (MCISABT), u'lrc rents an apartnrent u'ithrn walking distance oi the cafl, suggests thar w'e retreat to a table in the rear since her success has made it neatly impossible fbr her to live t INSET PI-lOTOGRAPHS BY ANDREw MAcPt-.rERsoN/coRBls #'\ 'lii s-l .** rffi: # g ':ry,- S .{ ili' .: ;Si', ,a .l# fact$ Sensing my surprise, she confesses, "Food is one of life's great pleasures; the chocolate cake here is a rare treat." Since she's already mentioned Flockhart (MGSA'88), I bring up her classmate's well-publicized thinness. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

The One with the Feminist Critique: Revisiting Millennial Postfeminism With

The One with the Feminist Critique: Revisiting Millennial Postfeminism with Friends In the years that followed the completion of its initial broadcast run, which came to an end on 6th (S10 E17 and 18), iconicMay millennial with USthe sitcom airing ofFriends the tenth (NBC season 1994-2004) finale The generated Last One only a moderate amount of scholarly writing. Most of it tended to deal with the series st- principally-- appointment in terms of its viewing institutional of the kindcontext, that and was to prevalent discuss it in as 1990s an example television of mu culture.see TV This, of course, was prior to the widespread normalization of time-shifted viewing practices to which the online era has since given rise (Lotz 2007, 261-274; Curtin and Shattuc 2009, 49; Gillan 2011, 181). Friends was also the subject of a small number of pieces of scholarship that entriesinterrogated that emerged the shows in thenegotiation mid-2000s of theincluded cultural politics of gender. Some noteworthy discussion of its liberal feminist individualism, and, for what example, she argued Naomi toRocklers be the postfeminist depoliticization of the hollow feminist rhetoric that intermittently rose to der, and in its treatment of prominence in the shows hierarchy of discourses of gen thatwomens interrogated issues . issues Theand sameproblems year arising also saw from the some publication of the limitationsof work by inherentKelly Kessler to ies (2006). The same year also sawthe shows acknowledgement depiction and in treatmenta piece by offeminist queer femininittelevision scholars Janet McCabe and Kim Akass of the significance of Friends as a key text of postfeminist television culture (2006). -

The Importance of Being Earnest SEETHU BABY MANGALAM 2020-2021 the Importance of Being Earnest Comedy of Manners

SUBJECT: BRITISH LITERATURE 19TH CENTURY TOPIC: The Importance of being Earnest SEETHU BABY MANGALAM 2020-2021 The Importance of being Earnest Comedy of Manners A Comedy of Manners is a play concerned with satirising society’s manners A manner is the method in which everyday duties are performed, conditions of society, or a way of speaking. It implies a polite and well-bred behaviour. Comedy of Manners is known as high comedy because it involves a sophisticated wit and talent in the writing of the script. In this sense it is both intellectual and very much the opposite of slapstick. Comedy of Manners In a Comedy of Manners however, there is often minimal physical action and the play may involve heavy use of dialogue. A Comedy of Manners usually employs an equal amount of both satire and farce resulting in a hilarious send-up of a particular social group. This was usually the middle to upper classes in society. The satire tended to focus on their materialistic nature, never-ending desire to gossip and hypocritical existence. Comedy of Manners The plot of such a comedy, usually concerned with an illicit love affair or similarly scandalous matter, is subordinate to the play’s brittle atmosphere, witty dialogue, and pungent commentary on human foibles. This genre is characterized by realism (art), social analysis and satire. These comedies held a mirror to the finer society of their age. These comedies are thus true pictures of the noble society of the age. This genre held a mirror to the high society of the Restoration Age. -

Cheers, Friends! the Story of Our Beer Zlatý Bažant 12° Tank

The story of our beer Zlatý Bažant 12° tank beer artfully brewed Superior ingredients are not enough when it comes to beer brewing. The thing that really counts is the craftsmanship of beer masters who keep an eye on the whole brewing process. They are experts who love their job and whose passion for beer and experience can’t be replaced by any modern machine. They brew Zlatý Bažant 12 artfully for you. Stored with care Zlatý Bažant is delivered to Klubovňa in a temperature stable tank right from the brewery. Afterwards it is pumped into smaller beer bags in our beautiful and modern stainless steel tanks. These beer bags are changed after each such filling in order to keep the beer in the best conditions. We keep beer chilled to ideal temperature of 7-10°C all the way. When your Bažant is draught from the tank, it is being pushed up by a compressor which pushes the air on the beer bag inside the tank. Doing it this way ensures that our artfully brewed Zlatý Bažant 12° tank beer will never get in touch with air, which guarantees the best beer quality on its way from brewery right into your glass. Artfully draught, served and enjoyed Brewing beer is a science. And drawing beer correctly is an art. Enjoy this premium lager beer of Pilsner type produced by traditional technology. It has a prominent well-balanced full taste, strong hops aroma and a pleasant bitter aftertaste. The malt from own malt plant provides it with the deep yellow color. -

Be Sure to MW-Lv/Ilci

Page 12 The Canadian Statesman. Bowmanville. April 29, 1998 Section Two From page 1 bolic vehicle taking its riders into other promised view from tire window." existences. Fit/.patriek points to a tiny figure peer In the Attic ing out of an upstairs window on an old photograph. He echoes that image in a Gwen MacGregor’s installation in the new photograph, one he took looking out attic uses pink insulation, heavy plastic of the same window with reflection in the and a very slow-motion video of wind glass. "I was playing with the idea of mills along with audio of a distant train. absence and presence and putting shifting The effect is to link the physical elements images into the piece." of the mill with the artist’s own memories growing up on the prairies. Train of Thought In her role as curator for the VAC, Toronto area artists Millie Chen and Rodgers attempts to balance the expecta Evelyn Michalofski collaborated on the tions of serious artists in the community Millery, millery, dustipoll installation with the demands of the general popula which takes its title from an old popular tion. rhyme. “There has to be a cultural and intel TeddyBear Club Holds Workshop It is a five-minute video projected onto lectual feeding," she says, and at the same Embroidered noses, button eyes, fuzzy cars, and adorable faces arc the beginnings of a beautiful teddy bear. three walls in a space where the Soper time, we have to continue to offer the So say the members of the Bowmanville Teddy Bear Club. -

Blacks Reveal TV Loyalty

Page 1 1 of 1 DOCUMENT Advertising Age November 18, 1991 Blacks reveal TV loyalty SECTION: MEDIA; Media Works; Tracking Shares; Pg. 28 LENGTH: 537 words While overall ratings for the Big 3 networks continue to decline, a BBDO Worldwide analysis of data from Nielsen Media Research shows that blacks in the U.S. are watching network TV in record numbers. "Television Viewing Among Blacks" shows that TV viewing within black households is 48% higher than all other households. In 1990, black households viewed an average 69.8 hours of TV a week. Non-black households watched an average 47.1 hours. The three highest-rated prime-time series among black audiences are "A Different World," "The Cosby Show" and "Fresh Prince of Bel Air," Nielsen said. All are on NBC and all feature blacks. "Advertisers and marketers are mainly concerned with age and income, and not race," said Doug Alligood, VP-special markets at BBDO, New York. "Advertisers and marketers target shows that have a broader appeal and can generate a large viewing audience." Mr. Alligood said this can have significant implications for general-market advertisers that also need to reach blacks. "If you are running a general ad campaign, you will underdeliver black consumers," he said. "If you can offset that delivery with those shows that they watch heavily, you will get a small composition vs. the overall audience." Hit shows -- such as ABC's "Roseanne" and CBS' "Murphy Brown" and "Designing Women" -- had lower ratings with black audiences than with the general population because "there is very little recognition that blacks exist" in those shows. -

73Rd-Nominations-Facts-V2.Pdf

FACTS & FIGURES FOR 2021 NOMINATIONS as of July 13 does not includes producer nominations 73rd EMMY AWARDS updated 07.13.2021 version 1 Page 1 of 20 SUMMARY OF MULTIPLE EMMY WINS IN 2020 Watchman - 11 Schitt’s Creek - 9 Succession - 7 The Mandalorian - 7 RuPaul’s Drag Race - 6 Saturday Night Live - 6 Last Week Tonight With John Oliver - 4 The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel - 4 Apollo 11 - 3 Cheer - 3 Dave Chappelle: Sticks & Stones - 3 Euphoria - 3 Genndy Tartakovsky’s Primal - 3 #FreeRayshawn - 2 Hollywood - 2 Live In Front Of A Studio Audience: “All In The Family” And “Good Times” - 2 The Cave - 2 The Crown - 2 The Oscars - 2 PARTIAL LIST OF 2020 WINNERS PROGRAMS: Comedy Series: Schitt’s Creek Drama Series: Succession Limited Series: Watchman Television Movie: Bad Education Reality-Competition Program: RuPaul’s Drag Race Variety Series (Talk): Last Week Tonight With John Oliver Variety Series (Sketch): Saturday Night Live PERFORMERS: Comedy Series: Lead Actress: Catherine O’Hara (Schitt’s Creek) Lead Actor: Eugene Levy (Schitt’s Creek) Supporting Actress: Annie Murphy (Schitt’s Creek) Supporting Actor: Daniel Levy (Schitt’s Creek) Drama Series: Lead Actress: Zendaya (Euphoria) Lead Actor: Jeremy Strong (Succession) Supporting Actress: Julia Garner (Ozark) Supporting Actor: Billy Crudup (The Morning Show) Limited Series/Movie: Lead Actress: Regina King (Watchman) Lead Actor: Mark Ruffalo (I Know This Much Is True) Supporting Actress: Uzo Aduba (Mrs. America) Supporting Actor: Yahya Abdul-Mateen II (Watchmen) updated 07.13.2021 version 1 Page -

General Cheers

NWA Kickball Cheers General Cheers Alamo: Kick it high. Kick it low. Kick it to the Alamo. Alamo, here we come. __________ is number one! Hot Dog: __________ wants a hot dog. __________ wants a coke. __________ wants a Home Run, and that's no joke! __________ wants a an orange. __________ wants a shake. __________ wants a to make it to Home Plate! Rock You [ Stomp, stomp, clap. Stomp, stomp, clap. ] We will, we will … Rock you down. Shake you up. Like a volcano ready to erupt. Watch out world. Here we come. __________ is number one! Froggy There was a little froggy -- sitting on a log He rooted for the other team -- it made no sense at all. We pushed him the water, and bonked his little head. And when he came back up again, this is what he said, he said: Go! Go, go! Go, mighty __________ . Fight! Fight, fight! Fight, mighty __________ . Win! Win, win! Win, mighty __________ . Go! Fight! WIn! Beat 'em till the end. Wooo! Big We’re BIG - B. I. G. And we’re BAD - B. A. D. And we’re BOSS - B. O. S. S. - B. O. S. S. - BOSS ! (REPEAT) We Are We are the __________ . Couldn't be prouder. If you can't hear us, we'll yell a little louder. (REPEAT - Louder each time) Stand Up Two bits! Four bits! Six bits! A dollar! All for the __________ stand up and holler! Call & Answer Cheers Dynamite: Our team is WHAT? DYNAMITE! Our team is WHAT? DYNAMITE! Our team is -- Hold on. -

Cheers, Friends!

CHEERS, FRIENDS! 7042 E. INDIAN SCHOOL RD. • SCOTTSDALE, AZ BLUECLOVERDISTILLERY.COM /BLUECLOVERDISTILLERY ENTRÉES ALWAYS HUNGRY SANDWICHES & BURGERS ALL SANDWICHES COME WITH YOUR CHOICE OF: SOUP • REGULAR FRIES • SWEET POTATO TOTS TACOS* $17 Served with 3 flour tortillas, creamed corn and black beans WE TAKE DIY LITERALLY. FISH — Grilled fish, cabbage, pineapple pico, From in-house distilled spirits to locally-sourced food salsa verde, green chili crema and cotija cheese, in our scratch kitchen, we are 100% hands-on. FARM EGG AND BACON GREEN CHILE GRILLED CHEESE* $14 CHEESEBURGER* $15 STEAK — Grilled steak, cabbage, tomato pico, salsa (V) 2 fried farm eggs with strips of bacon served 7-ounce chuck and brisket blend served on a verde, cilantro and queso blanco HOUSE VEGETARIAN on sourdough with melted pepper jack cheese, potato bun with green chile, pepper jack cheese, SPECIALTY ITEM arugula and truffle aioli mayonnaise, lettuce, onions and tomatoes CHICKEN — Grilled chicken, cabbage, cilantro, + BACON* $2 salsa verde and queso blanco BC PASTRAMI $14 STARTERS SOUPS Carnegie deli New York pastrami served on CLASSIC BURGER* $14 CLASSIC CHICKEN STRIPS* $14 sourdough with Havarti cheese, sauerkraut and 7-ounce chuck and brisket blend served on a 4 country-fried chicken strips, accompanied with a house Russian dressing potato bun with cheddar cheese, lettuce, onions, fries; with chorizo gravy and BBQ dipping sauce tomatoes and mayo HOUSE CHIPS AND SALSA $7 CHICKEN TORTILLA $5 BLUE CLOVER KICKER $15 + BACON* $2 SMOKED SALMON* $18 House-made