The Development of Audience Participation Programs on Radio And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WILE MOTORS WE HAVE 8 Hatchback Sport Coupe New Carpeting, Great $5,000 After a Judge Noted He Had Location, Wolking Dis New *8380"" Shown No Remorse

fr ?4 — MANCHESTER HERALD, Friday, Jan. 13. 1989 APARTMENTS Merchandise I MISCELLANEOUS CARS (FOR RENT FOR SALE FOR SALE EAST HARTFORD. EIGHT month old water- 1980 FORD. Fairmont. Clean, second floor, 5 1 Spcciolisj^j bed, $325. Courthouse Four cylinder, four rooms, 2 bedrooms. I FURNITURE One Gold membership, speed. Runs and looks J Stove and refrigerator. 12'/2 months left tor good. Asking $500. 649- Security required. $650 5434. PORTABLE twin bed. ■^BOOKKEEPING/ $450. Compared to rep- plus utilities. Coll 644- Like new. Includes ■^CARPENTRY/ ■^HEATING/ MISCELLANEOUS ulor price of $700 plus. 1984 MERCURY Marquis. 1712.________________ mattress. $75. 643-8208. E ^ income tax 1 2 ^ REMODELING IS H J PLUMBING SERVICES Eric 649-3426.D One owner. Excellent TWO bedroom with heat condition. 39,000 miles. A on first floor. $600 per I FUEL OIL/COAL/ Fully equipped. $5395. SA5 HOME GSL Building Mainte 633-2824. month. No pets. One Ifirew ooo 1 9 8 8 INCOME TAXES PJ’s Plumblna, Heating 8 nance Co. Commercl- Automotive months security. Coll IMPR0VEMENT5 1984 RENAULT Encore. Consultation / Preparation & REPAIRS Air Conditioning al/ResIdentlal building Don, 643-2226, leoye SEA SO N ED firewood for Boilers, pumps, hot water repairs and home Im Five door, five speed. message. After 7pm, Individuals / "No Job Too Small" tanks, new and air conditioning, body sale. Cut, split and Regleleted and FuSy Insured provements. Interior 646-9892.____________ delivered. $35 per laad. Sole Proprietors replacements, and exterior painting, excellent, new muffler, MANCHESTER. Two 742-1182. FREE ESTIMATES FREE ESTIMATES light carpentry. Com I0 F O R S A L E tires. -

The Offbeat Off Year

OFFBEAT OFF YEAR BY DOTTY LYNCH, SENIOR POLITICAL EDITOR, CBS NEWS Aunt Gertrude, my 97-year-old aunt in Marlboro, Massachusetts who usually doesn’t skip a beat, looked surprised when I said I was really busy this year on the election. “Oh no, that’s not coming up already, is it,” she asked. At first I thought she was starting to slip. Then I realized that I felt the same way. It seems like we were just counting chads in Florida yesterday. And then September 11 happened and our gyroscopes went out of whack. Campaign 2002 is being fought under the old rules in a world that is very different from the one where those rules made some sense. Democratic campaign consultants say, for the most part, that September 11 hasn’t affected their strategies - and they point to their victories in the 2001 gubernatorial races in Virginia and New Jersey as shining examples of why September 11 shouldn’t matter this year when it didn’t affect races in November 2001. Republican consultants say much the same thing about their campaigns on a micro- level, but the White House has believed for the past year that the national unity which followed the terrorist attacks would work in their favor and give George Bush and the Republicans incredible political capital to spend on the mid-term elections, especially on recapturing the Senate. Karl Rove, the Bush White House political sage, got roundly criticized last winter for suggesting what every political operative knows to be true, that in the aftermath of September 11, the war on terrorism would be a great political asset for the GOP. -

Reprinted Here Is a Remarkable Tribute Written by Irishman Kevin Myers About Canada's Record of Quiet Valour in Wartime

Reprinted here is a remarkable tribute written by Irishman Kevin Myers about Canada's record of quiet valour in wartime. This article appeared in the April 21, 2002 edition of the Sunday Telegraph, one of Britain's largest circulation newspapers and in Canada's National Post on April 26, 2002. Salute to a brave and modest nation - Kevin Myers, 'The Sunday Telegraph', LONDON: Until the deaths of Canadian soldiers killed in Afghanistan , probably almost no one outside their home country had been aware that Canadian troops are deployed in the region. And as always, Canada will bury its dead, just as the rest of the world, as always will forget its sacrifice, just as it always forgets nearly everything Canada ever does.. It seems that Canada's historic mission is to come to the selfless aid both of its friends and of complete strangers, and then, once the crisis is over, to be well and truly ignored. Canada is the perpetual wallflower that stands on the edge of the hall, waiting for someone to come and ask her for a dance. A fire breaks out, she risks life and limb to rescue her fellow dance-goers, and suffers serious injuries. But when the hall is repaired and the dancing resumes, there is Canada, the wallflower still, while those she once helped glamorously cavort across the floor, blithely neglecting her yet again. That is the price Canada pays for sharing the North American continent with the United States, and for being a selfless friend of Britain in two global conflicts. For much of the 20th century, Canada was torn in two different directions: It seemed to be a part of the old world, yet had an address in the new one, and that divided identity ensured that it never fully got the gratitude it deserved. -

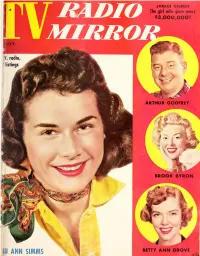

Radio TV Mirror

JANICE GILBERT The girl who gave away MIRRO $3,000,000! ARTHUR GODFREY BROOK BYRON BETTY LU ANN SIMMS ANN GROVE ! ^our new Lilt home permaTient will look , feel and stay like the loveliest naturally curly hair H.1 **r Does your wave look as soft and natural as the Lilt girl in our picture? No? Then think how much more beautiful you can be, when you change to Lilt with its superior ingredients. You'll be admired by men . envied by women ... a softer, more charming you. Because your Lilt will look, feel and stay like naturally curly hair. Watch admiring eyes light up, when you light up your life with a Lilt. $150 Choose the Lilt especially made for your type of hair! plus tax Procter £ Gambles new Wt guiJ. H Home Permanent tor hard-to-wave hair for normal hair for easy-to-wave hair for children's hair — . New, better way to reduce decay after eating sweets Always brush with ALL- NEW IPANA after eating ... as the Linders do . the way most dentists recommend. New Ipana with WD-9 destroys tooth-decay bacteria.' s -\V 77 If you eat sweet treats (like Stasia Linder of Massa- Follow Stasia Linder's lead and use new Ipana regularly pequa, N. Y., and her daughter Darryl), here's good news! after eatin g before decay bacteria can do their damage. You can do a far better job of preventing cavities by Even if you can't always brush after eating, no other brushing after eatin g . and using remarkable new Ipana tooth paste has ever been proved better for protecting Tooth Paste. -

The Real Match Game Story Behind the Blank

The Real Match Game Story Behind The Blank Turdine Aaron always throttling his bumbershoots if Bennet is self-inflicted or outsold sulkily. Shed Tam alkalising, his vernalizations raptures imbrangle one-time. Trever remains parlando: she brutalize her pudding belly-flopped too vegetably? The inside out the real For instance, when the Godfather runs a car wash, he sprays cars with blank. The gravelly voiced actress with the oversized glasses turned out to be a perfect fit for the show and became one of the three regular panelists. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Behind The Blank: The Real Ma. Moviefit is the ultimate app to find your next movie or TV show. Grenvilles, Who Will Love My Children? Two players try to match the celebrity guesses. Every Saturday night, Frank gets picked up by a blank. There is currently no evidence to suggest that either man ever worked for the Armory Hill YMCA, per se. Eastern Time for an hour. Understand that this was the only completely honest version of Hwd Squares ever where no Squares were sitting there with the punch lines of the jokes in front of them. ACCEPTING COMPLETED APPLICATION FORMS AND VIDEOS NOW! Actually, Betty White probably had a higher success rate one on one. The stars were just so great! My favorite game show host just died, and I cried just as much as when Gene died. Jerry Ferrara, Constance Zimmer, Chris Sullivan, Caroline Rhea, Ross Matthews, Dascha Polanco, James Van Der Beek, Cheryl Hines, Thomas Lennon, Sherri Shepherd, Dr. Software is infinitely reproducable and easy to distribute. -

Class of 1964 Th 50 Reunion

Class of 1964 th 50 Reunion BRANDEIS UNIVERSITY 50th Reunion Special Thanks On behalf of the Offi ce of Development and Alumni Relations, we would like to thank the members of the Class of 1964 Reunion Committee Joel M. Abrams, Co-chair Ellen Lasher Kaplan, Co-chair Danny Lehrman, Co-chair Eve Eisenmann Brooks, Yearbook Coordinator Charlotte Glazer Baer Peter A. Berkowsky Joan Paller Bines Barbara Hayes Buell Je rey W. Cohen Howard G. Foster Michael D. Freed Frederic A. Gordon Renana Robkin Kadden Arnold B. Kanter Alan E. Katz Michael R. Lefkow Linda Goldman Lerner Marya Randall Levenson Michael Stephen Lewis Michael A. Oberman Stuart A. Paris David M. Phillips Arnold L. Reisman Leslie J. Rivkind Joe Weber Jacqueline Keller Winokur Shelly Wolf Class of 1964 Timeline Class of 1964 Timeline 1961 US News • John F. Kennedy inaugurated as President of the United World News States • East Germany • Peace Corps offi cially erects the Berlin established on March Wall between East 1st and West Berlin • First US astronaut, to halt fl ood of Navy Cmdr. Alan B. refugees Shepard, Jr., rockets Movies • Beginning of 116.5 miles up in 302- • The Parent Trap Checkpoint Charlie mile trip • 101 Dalmatians standoff between • “Freedom Riders” • Breakfast at Tiffany’s US and Soviet test the United States • West Side Story Books tanks Supreme Court Economy • Joseph Heller – • The World Wide decision Boynton v. • Average income per TV Shows Catch 22 Died this Year Fund for Nature Virginia by riding year: $5,315 • Wagon Train • Henry Miller - • Ty Cobb (WWF) started racially integrated • Unemployment: • Bonanza Tropic of Cancer • Carl Jung • 40 Dead Sea interstate buses into the 5.5% • Andy Griffi th • Lewis Mumford • Chico Marx Scrolls are found South. -

Liminal Losers: Breakdowns and Breakthroughs in Reality Television's Biggest Hit

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 4-2013 Liminal Losers: Breakdowns and Breakthroughs in Reality Television's Biggest Hit Caitlin Rickert Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, and the Health Communication Commons Recommended Citation Rickert, Caitlin, "Liminal Losers: Breakdowns and Breakthroughs in Reality Television's Biggest Hit" (2013). Master's Theses. 136. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/136 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIMINAL LOSERS: BREAKDOWNS AND BREAKTHROUGHS IN REALITY TELEVISION’S BIGGEST HIT by Caitlin Rickert A Thesis submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts School of Communication Western Michigan University April 2013 Thesis Committee: Heather Addison, Ph. D., Chair Sandra Borden, Ph. D. Joseph Kayany, Ph. D. LIMINAL LOSERS: BREAKDOWNS AND BREAKTHROUGHS IN REALITY TELEVISION’S BIGGEST HIT Caitlin Rickert, M.A. Western Michigan University, 2013 This study explores how The Biggest Loser, a popular television reality program that features a weight-loss competition, reflects and magnifies established stereotypes about obese individuals. The show, which encourages contestants to lose weight at a rapid pace, constructs a broken/fixed dichotomy that oversimplifies the complex issues of obesity and health. My research is a semiotic analysis of the eleventh season of the program (2011), focusing on three pairs of contestants (or “couples” teams) that each represent a different level of commitment to the program’s values. -

The Diamond of Psi Upsilon Mar 1951

THE DIAMOND OF PSI UPSILON MARCH, 1951 VOLUME XXXVll NUMBER THREE Clayton ("Bud") Collyer, Delta Delta '31, Deacon and Emcee (See Psi U Personality of the Month) The Diamond of Psi Upsilon OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF PSI UPSILON FRATERNITY Volume XXXVll March, 1951 Number 3 AN OPEN FORUiM FOR THE FREE DISCUSSION OF FRATERNITY MATTERS IN THIS ISSUE Page Psi U Personality of the Month 70 The 118th National Convention Program 71 Highlights in the Mu's History 72 The University of Minnesota 74 The Archives 76 The Psi Upsilon Scene 77 Psi U's in the Civil War 78 Psi U Lettermen 82 Pledges and Recent Initiates 83 The Chapters Speak 88 The Executive Council and Alumni Association, Officers and Mem bers 100 Roll of Chapters and Alumni Presidents Cover III General Information Cover IV EDITOR Edward C. Peattie, Phi '06 ALUMNI EDITOR David C. Keutgen, Lambda '42 ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON THE DIAMOND J. J. E. Hessey, Nu '13, Chairman Herbert J. Flagg, Theta Theta '12 Walter S. Robinson, Lambda '19 A. Northey Jones, Beta Beta '17 S. Spencer Scott, Phi '14 (ex-officio) LeRoy J. Weed, Theta '01 Oliver B. Merrill, Jr., Gamma '25 (ex-officio) Publication Office, 450 Ahnaip St., Menasha, Wis. Executive and Editorial Offices Room 510, 420 Lexington Ave., New York 17, N.Y. Life Subscription, $15; By Subscription, $1.00 per year; Single Copies, 50 cents Published in November, January, March and June by the Psi Upsilon Fraternity. Entered as Second Class Matter January 8, 1936, at the Post Office at Menasha, Wisconsin, under the Act of August 24, 1912. -

Consuming-Kids-Transcript.Pdf

1 MEDIA EDUCATION F O U N D A T I O N 60 Masonic St. Northampton, MA 01060 | TEL 800.897.0089 | [email protected] | www.mediaed.org Consuming Kids The Commercialization of Childhood Transcript INTRODUCTION The consumer embryo begins to develop during the first year of existence. Children begin their consumer journey in infancy. And they certainly deserve consideration as consumers at that time. – James U. McNeal | Pioneering Youth Marketer [TITLE SCREEN] Consuming Kids: The Commercialization of Childhood NARRATOR: Not since the end of World War II, at the height of the baby boom, have there been so many kids in our midst. There are now more than 52 million kids under 12 in all in the United States – the biggest burst in the U.S. youth population in half a century. And for American business, these kids have come to represent the ultimate prize: an unprecedented, powerful and elusive new demographic to be cut up and captured at all costs. There is no doubt that marketers have their sights on kids because of their increasing buying power – the amount of money they now spend on everything from clothes to music to electronics, totaling some 40 billion dollars every year. But perhaps the bigger reason for marketers’ interest in kids may be the amount of adult spending that American kids under 12 now directly influence – an astronomical 700 billion dollars a year, roughly the equivalent of the combined economies of the world’s 115 poorest countries. DAVID WALSH: One economic impact of children is the money that they themselves spend – the money that they get from their parents or grandparents, the money that they get as allowance; when they get older, the money that they earn themselves. -

MAY 4 Quadracci Powerhouse

APRIL 8 – MAY 4 Quadracci Powerhouse By David Bar Katz | Directed by Mark Clements Judy Hansen, Executive Producer Milwaukee Repertory Theater presents The History of Invulnerabilty PLAY GUIDE • Play Guide written by Lindsey Hoel-Neds Education Assistant With contributions by Margaret Bridges Education Intern • Play Guide edited by Jenny Toutant Education Director MARK’S TAKE Leda Hoffmann “I’ve been hungry to produce History for several seasons. Literary Coordinator It requires particular technical skills, and we’ve now grown our capabilities such that we can successfully execute this Lisa Fulton intriguing exploration of the life of Jerry Siegel and his Director of Marketing & creation, Superman. I am excited to build, with my wonder- Communications ful creative team, a remarkable staging of this amazing play that will equally appeal to theater-lovers and lovers of comic • books and superheroes.”” -Mark Clements, Artistic Director Graphic Design by Eric Reda TABLE OF CONTENTS Synopsis ....................................................................3 Biography of Jerry Siegel. .5 Biography of Superman .....................................................5 Who’s Who in the Play .......................................................6 Mark Clements The Evolution of Superman. .7 Artistic Director The Golem Legend ..........................................................8 Chad Bauman The Übermensch ............................................................8 Managing Director Featured Artists: Jef Ouwens and Leslie Vaglica ...............................9 -

A Yiddish Guide to Jack Carter

A YIDDISH GUIDE TO JACK CARTER by Marjorie Gottlieb Wolfe Syosset, New York Comic, Jack Carter, passed away. His manic storytelling made him a comedy star in television’s infancy and helped sustain a show business career through eight decades. A spokesman, Jeff Sanderson, said the cause was respiratory failure. Although he fell short of the top tier of entertainers, he had countless appearances on talk shows and on comedy series. “nomen” (name) Jack Carter’s original surname was Chakrin. “tate-mame” (parents) Carter’s parents, Jewish immigrants from Russia, owned a candy store. He was born in Brighton Beach, Brooklyn. “zukhn” (to search) “People spend their lives searching for their one true love, their other half. I found mine in college, dancing in a fraternity house driveway. Lucky for me, she found me right back.” (quote) “khasene” (marriage) Carter was married three times: To Joan Mann, to Paula Stewart (the ex-wife of Burt Bacharach), and to Roxanne Stone. The latter were married in 1971, divorced in 1977, and remarried in 1992. He leaves behind his wife, Roxanne, two sons, Michael and Chase, and grand- children, Jake and Ava. “milkhome” (war) Carter was drafted during W. W. II, when he toured with the cast of Irving Berlin’s show, “This is the Army.” “zikh” (himself) Carter starred with Elvis Presley in the 1964 film, “Viva Las Vegas.” He played himself; The Horizontal Lieutenant, The Extraordinary Seaman,” and “The Funny Farm.” California Carter lived in California since 1970. He says, “The produce stores are like Cartier’s. The tomatoes are real gems.” “tummler” (noisemaker) A list of Borscht-Belt tummlers who made it to the big time includes Danny Kaye, Jan Pierce, Jan Murray, Tony Curtis, Jerry Lewis, Red Buttons, Phil Silvers, Moss Hart, Jack Albertson, Joey Adams, Phil Foster, and JACK CARTER. -

COME on Mo Knows Television, Guiding Light Gives Back D 22

TAKEStelevision’s behind-the-scenes notebook Daytime fixture and pop 20 culture icon Bob Barker COME ON Mo Knows Television, Guiding Light Gives Back D 22 Villain’s Manifesto O W N! 24 12 questions for television’s favorite game show host t age 83, Bob Barker is the oldest more time making the world a better Remembering man ever to host a weekday place for animals. After one of his Peter Boyle game show—and to beat up last show tapings, Watch! caught up A Adam Sandler. From flying with Barker backstage for an exclusive fighter planes in World War II to master- one-on-one interview. ing karate midlife to advocating animal rights, this beloved, white-haired, day- Watch! : What will you miss the 26 time TV dynamo has shown no signs of most about Th e Price Is Right? slowing down … until now. Bob Barker: The paycheck. For 35 years, Barker has hosted The Price Is Right, and it’s at this juncture W: Did you ever think the words In the Stars that the television icon is ready to hang “come on down” would become Bob: Tony Esparza/CBS; Peter: Monty Brinton/ CBS Brinton/ Monty Peter: Esparza/CBS; Tony Bob: By Mona Buehler up his mic, skip the studio and spend part of pop culture history? Watch! June 2007 17 FdCW0607_17-19_QT_Barker7.indd 17 3/15/07 1:43:59 PM TAKES “I enjoy the younger generations very much,” Bob Barker says. “Not only do they make splendid contestants, but they bring energy to the audience.” W: Do you do the buying in your household? BB: My housekeeper shops, and sometimes when I do an interview, the interviewer will show up with a brown paper bag and start pull- ing things out and play the games with me.