Documentary Reality Television's Privacy Problem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT This Copy of the Thesis Has Been

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk 04 University of Plymouth Research Theses 01 Research Theses Main Collection 2012 Life Expansion: Toward an Artistic, Design-Based Theory of the Transhuman / Posthuman Vita-More, Natasha http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/1182 University of Plymouth All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. COPYRIGHT STATEMENT This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognize that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author’s prior consent. 1 Life Expansion: Toward an Artistic, Design-Based Theory of the Transhuman / Posthuman by NATASHA VITA-MORE A thesis submitted to the University of Plymouth in partial fulfillment for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Art & Media Faculty of Arts April 2012 2 Natasha Vita-More Life Expansion: Toward an Artistic, Design-Based Theory of the Transhuman / Posthuman The thesis’ study of life expansion proposes a framework for artistic, design-based approaches concerned with prolonging human life and sustaining personal identity. To delineate the topic: life expansion means increasing the length of time a person is alive and diversifying the matter in which a person exists. -

KANG-THESIS.Pdf (614.4Kb)

Copyright by Jennifer Minsoo Kang 2012 The Thesis Committee for Jennifer Minsoo Kang Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: From Illegal Copying to Licensed Formats: An Overview of Imported Format Flows into Korea 1999-2011 APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Joseph D. Straubhaar Karin G. Wilkins From Illegal Copying to Licensed Formats: An Overview of Imported Format Flows into Korea 1999-2011 by Jennifer Minsoo Kang, B.A.; M.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 Dedication To my family; my parents, sister and brother Abstract From Illegal Copying to Licensed Formats: An Overview of Imported Format Flows into Korea 1999-2011 Jennifer Minsoo Kang, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2012 Supervisor: Joseph D. Straubhaar The format program trade has grown rapidly in the past decade and has become an important part of the global television market. This study aimed to give an understanding of this phenomenon by examining how global formats enter and become incorporated into the national media market through a case study analysis on the Korean format market. Analyses were done to see how the historical background influenced the imported format flows, how the format flows changed after the media liberalization period, and how the format uses changed from illegal copying to partial formats to whole licensed formats. Overall, the results of this study suggest that the global format program flows are different from the whole ‘canned’ program flows because of the adaptation processes, which is a form of hybridity, the formats go through. -

Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Film, Media & Theatre Dissertations School of Film, Media & Theatre Spring 5-6-2019 Dynamics of a Periphery TV Industry: Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats Soo keung Jung [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/fmt_dissertations Recommended Citation Jung, Soo keung, "Dynamics of a Periphery TV Industry: Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2019. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/fmt_dissertations/7 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Film, Media & Theatre at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Film, Media & Theatre Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DYNAMICS OF A PERIPHERY TV INDUSTRY: BIRTH AND EVOLUTION OF KOREAN REALITY SHOW FORMATS by SOOKEUNG JUNG Under the Direction of Ethan Tussey and Sharon Shahaf, PhD ABSTRACT Television format, a tradable program package, has allowed Korean television the new opportunity to be recognized globally. The booming transnational production of Korean reality formats have transformed the production culture, aesthetics and structure of the local television. This study, using a historical and practical approach to the evolution of the Korean reality formats, examines the dynamic relations between producer, industry and text in the -

Class of 1964 Th 50 Reunion

Class of 1964 th 50 Reunion BRANDEIS UNIVERSITY 50th Reunion Special Thanks On behalf of the Offi ce of Development and Alumni Relations, we would like to thank the members of the Class of 1964 Reunion Committee Joel M. Abrams, Co-chair Ellen Lasher Kaplan, Co-chair Danny Lehrman, Co-chair Eve Eisenmann Brooks, Yearbook Coordinator Charlotte Glazer Baer Peter A. Berkowsky Joan Paller Bines Barbara Hayes Buell Je rey W. Cohen Howard G. Foster Michael D. Freed Frederic A. Gordon Renana Robkin Kadden Arnold B. Kanter Alan E. Katz Michael R. Lefkow Linda Goldman Lerner Marya Randall Levenson Michael Stephen Lewis Michael A. Oberman Stuart A. Paris David M. Phillips Arnold L. Reisman Leslie J. Rivkind Joe Weber Jacqueline Keller Winokur Shelly Wolf Class of 1964 Timeline Class of 1964 Timeline 1961 US News • John F. Kennedy inaugurated as President of the United World News States • East Germany • Peace Corps offi cially erects the Berlin established on March Wall between East 1st and West Berlin • First US astronaut, to halt fl ood of Navy Cmdr. Alan B. refugees Shepard, Jr., rockets Movies • Beginning of 116.5 miles up in 302- • The Parent Trap Checkpoint Charlie mile trip • 101 Dalmatians standoff between • “Freedom Riders” • Breakfast at Tiffany’s US and Soviet test the United States • West Side Story Books tanks Supreme Court Economy • Joseph Heller – • The World Wide decision Boynton v. • Average income per TV Shows Catch 22 Died this Year Fund for Nature Virginia by riding year: $5,315 • Wagon Train • Henry Miller - • Ty Cobb (WWF) started racially integrated • Unemployment: • Bonanza Tropic of Cancer • Carl Jung • 40 Dead Sea interstate buses into the 5.5% • Andy Griffi th • Lewis Mumford • Chico Marx Scrolls are found South. -

Liminal Losers: Breakdowns and Breakthroughs in Reality Television's Biggest Hit

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 4-2013 Liminal Losers: Breakdowns and Breakthroughs in Reality Television's Biggest Hit Caitlin Rickert Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, and the Health Communication Commons Recommended Citation Rickert, Caitlin, "Liminal Losers: Breakdowns and Breakthroughs in Reality Television's Biggest Hit" (2013). Master's Theses. 136. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/136 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIMINAL LOSERS: BREAKDOWNS AND BREAKTHROUGHS IN REALITY TELEVISION’S BIGGEST HIT by Caitlin Rickert A Thesis submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts School of Communication Western Michigan University April 2013 Thesis Committee: Heather Addison, Ph. D., Chair Sandra Borden, Ph. D. Joseph Kayany, Ph. D. LIMINAL LOSERS: BREAKDOWNS AND BREAKTHROUGHS IN REALITY TELEVISION’S BIGGEST HIT Caitlin Rickert, M.A. Western Michigan University, 2013 This study explores how The Biggest Loser, a popular television reality program that features a weight-loss competition, reflects and magnifies established stereotypes about obese individuals. The show, which encourages contestants to lose weight at a rapid pace, constructs a broken/fixed dichotomy that oversimplifies the complex issues of obesity and health. My research is a semiotic analysis of the eleventh season of the program (2011), focusing on three pairs of contestants (or “couples” teams) that each represent a different level of commitment to the program’s values. -

Pocket Product Guide 2006

THENew Digital Platform MIPTV 2012 tm MIPTV POCKET ISSUE & PRODUCT OFFILMGUIDE New One Stop Product Guide Search at the Markets Paperless - Weightless - Green Read the Synopsis - Watch the Trailer BUSINESSC onnect to Seller - Buy Product MIPTVDaily Editions April 1-4, 2012 - Unabridged MIPTV Product Guide + Stills Cher Ami - Magus Entertainment - Booth 12.32 POD 32 (Mountain Road) STEP UP to 21st Century The DIGITAL Platform PUBLISHING Is The FUTURE MIPTV PRODUCT GUIDE 2012 Mountain, Nature, Extreme, Geography, 10 FRANCS Water, Surprising 10 Francs, 28 Rue de l'Equerre, Paris, Delivery Status: Screening France 75019 France, Tel: Year of Production: 2011 Country of +33.1.487.44.377. Fax: +33.1.487.48.265. Origin: Slovakia http://www.10francs.f - email: Only the best of the best are able to abseil [email protected] into depths The Iron Hole, but even that Distributor doesn't guarantee that they will ever man- At MIPTV: Yohann Cornu (Sales age to get back.That's up to nature to Executive), Christelle Quillévéré (Sales) decide. Office: MEDIA Stand N°H4.35, Tel: + GOOD MORNING LENIN ! 33.6.628.04.377. Fax: + 33.1.487.48.265 Documentary (50') BEING KOSHER Language: English, Polish Documentary (52' & 92') Director: Konrad Szolajski Language: German, English Producer: ZK Studio Ltd Director: Ruth Olsman Key Cast: Surprising, Travel, History, Producer: Indi Film Gmbh Human Stories, Daily Life, Humour, Key Cast: Surprising, Judaism, Religion, Politics, Business, Europe, Ethnology Tradition, Culture, Daily life, Education, Delivery Status: Screening Ethnology, Humour, Interviews Year of Production: 2010 Country of Delivery Status: Screening Origin: Poland Year of Production: 2010 Country of Western foreigners come to Poland to expe- Origin: Germany rience life under communism enacted by A tragicomic exploration of Jewish purity former steel mill workers who, in this way, laws ! From kosher food to ritual hygiene, escaped unemployment. -

TV Formats Worldwide Localizing Global Programs

TV Formats Worldwide Localizing Global Programs Edited by Albert Moran intellect Bristol, UK / Chicago, USA Contents PARTI: INTRODUCTION 7 Chapter 1: Introduction: 'Descent and Modification' 9 Albert Moran PARTII: MODELLINGAND THEORY-BUILDING 25 Chapter 2: Rethinking the Local-Global Nexus Through Multiple Modernities: The Case of Arab Reality Television 27 Marwan M. Kraidy Chapter 3: When TV Formats are Translated 39 Albert Moran Chapter 4: Imagining the National: Gatekeepers and the Adaptation of Global Franchises in Argentina 55 Silvio Waisbord and Sonia Jalfin PARTIII: INSTITUTIONALAPPROACHES 75 Chapter 5: Trading in TV Entertainment: An Analysis 77 Katja Lantzsch, Klaus-Dieter Altmeppen and Andreas Will Chapter 6: The Rise of the Business Entertainment Format on British Television 97 Raymond Boyle Chapter 7: Collaborative Reproduction of Attraction and Performance: The Case of the Reality Show Idol 113 Yngver Njus Chapter 8: Auditioning for Idol: The Audience Dimension of Format Franchising 129 Doris Baltruschat TV Formats Worldwide PART IV: COMPARATIVECROSS-BORDERSTUDIES 147 Chapter 9: Adapting Global Television to Regional Realities: Traversing the Middle East Experience 149 Amos Owen Thomas Chapter 10: How National Media Systems Shape the Localization of Formats: A Transnational Case Study of The Block and Nerds Fe in Australia and Denmark 163 Pia Majbrit Jensen Chapter 11: Transcultural Localization Strategies of Global TV Formats: The Office and Stromberg 187 Edward Larkey Chapter 12: Tearing Up Television News Across Borders: -

Television Reform Ir Broadcasting Blues Nem Zealand

Television Reform ir Nem Zealand - l The underlying dilemma is the small j size o f the New Zealand market, which, Broadcasting Blues or Blue Sky? I with a population o f four million, j limits the profitability o f multiple The New Zealand television industry has a charter which requires it to fulfil various | television operators, and means been the subject o f various reforms since cultural objectives. Questions remain about \ funding o f local content and public 1999 dealing with local content, diversity of how the new charter obligations will be funded \ service broadcasting is an ongoing and programming, digital broadcasting, the role over the long term and whether TVNZ will be i difficult issue. of the public broadcaster and funding. Marion successful in balancing a public service role \ Jacka examines these developments, remarking with a commercial imperative. The government broadcasting between two organisations - TVNZ on the distinctive features of the New Zealand has declined to introduce mandatory local and NZ On Air - which would pursue each market and the commitment to social and content quotas and has opted instead for a self- of these objectives independently (Spicer et cultural objectives. regulatory scheme similar to the approach being a I 1996, p. 15). The public funding previously taken to New Zealand music on commercial allocated to BCNZ and collected in the form of Overview radio. a public broadcasting fee was transferred to NZ Many New Zealanders have the While there has been some dissatisfaction with On Air. The role of this agency was to promote broadcasting blues. They want TV and radio the pace of reform from the film and television universal access, 'minority programming', and of a higher calibre (Christchurch Press, 2 production industry and various commentators, programs which reflect New Zealand identity February 2000, p. -

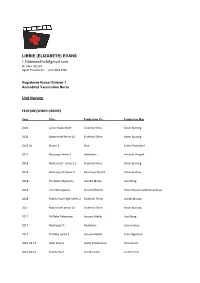

EVANS Libbie CV

LIBBIE (ELIZABETH) EVANS E: [email protected] M: 0409 195 247 Agent: Freelancers +613 9682 2722 Registered Nurse Division 1 Accredited Vaccination Nurse Unit Nursing FEATURE/SERIES CREDITS Year Title Production Co. Production Mgr 2020 Junior Masterchef Endemol Shine Karen Bunting 2020 Masterchef Series 12 Endemol Shine Karen Bunting 2019-20 Bloom 2 Stan Esther Rodewald 2019 Mustangs Series 3 Matchbox Amanda WrayeE 2018 Masterchef Series 11 Endemol Shine Karen Bunting 2018- Mustangs FC Series 2 Mustangs Pty Ltd Amanda Wray 2018- The Blake Mysteries Gambit Media Lisa Wang 2018 The InBestigators Gristmill/Netfix Peter Muston (additional days) 2018- Family Food Fight Series 2 Endemol Shine Lyndal Murray 2017 Masterchef Series 10 Endemol Shine Karen Bunting 2017 Dr Blake Telemovie January Media Lisa Wang 2017 Mustangs FC Matchbox Jane Lindsey 2017 Dr Blake series 5 January Media Elisa Argentisio 2016-04-12 Little Acorns Guilty Productions Tom Davies 2016-04-12 Family Feud Ten Network Caitlin Finch Year Title Production Co. Production Mgr. 2015 Dr Blake Series 4 January Media Ross Allsop 2015 Jack Irish Essential M Jane Sullivan 2015 Winners and Losers Channel 7 Naomi Mulholland 2015- Childhoods’ End Haypop Pty Ltd Wade Savage 2014 Masterchef Shine Australia Megan Brock 2014 The Secret River Ruby Entertainment Lesley Parker 2014 Gallipoli Endemol Australia Deborah Glover 2014 Masterchef Shine Australia Michaela Sampson 2013 Dr Blake Series 2 January Productions Ross Allsop/ Naomi Mulholland 2013 Worst Year of My Life Again Worst Year Productions -

To Teach and to Please: Reality TV As an Agent of Societal Change

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by eScholarship@BC To Teach and to Please: Reality TV as an Agent of Societal Change Author: Robert J. Vogel Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/2653 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2012 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. To Teach and to Please: Reality TV as an Agent of Societal Change Robert Vogel Undergraduate Honors Thesis William E. Stanwood, Thesis Advisor Boston College December 2011 i Acknowledgements Many people have contributed to the completion of this senior thesis. First and foremost, I would like to recognize my family for encouraging me to attempt new things, and to always pursue a challenging course of study. My mother and father have shown nothing but the utmost love and support for me in every venture (and adventure) that I have undertaken, and I am eternally thankful to them. Further, I want to recognize my peers. First, my roommates: Drew Galloway, Jay Farmer, Dan Campbell, Fin O’Neill, and (at one time) Jonah Tomsick. Second, my a capella group, the BC Acoustics. Third, my friends, both from Boston College and from home (you know who you are). And fourth, my wonderful girlfriend, Sarah Tolman. Having no siblings, I embrace my close friends as my family. Each one of you gave me inspiration, determination, love, laughter, and support during the conducting of this research, and I sincerely thank you for this. -

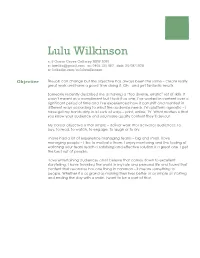

Lulu Wilkinson A: 5 Ocean Grove Collaroy NSW 2097 E: [email protected] M: 0402 120 597 Dob: 25/08/1978 W: Linkedin.Com/In/Luluwilkinson

Lulu Wilkinson a: 5 Ocean Grove Collaroy NSW 2097 e: [email protected] m: 0402 120 597 dob: 25/08/1978 w: linkedin.com/in/luluwilkinson Objective The job can change but the objective has always been the same – create really great work and have a good time doing it. Oh - and get fantastic results. Someone recently described me as having a “too diverse, erratic” set of skills. It wasn’t meant as a compliment but I took it as one. I’ve worked in content over a significant period of time and I’ve experienced how it can shift and manifest in different ways according to what the audience needs. I’m platform agnostic – I have got my hands dirty in all sorts of ways – print, online, TV. What matters is that you know your audience and you make quality content they’ll devour. My career objective is that simple – deliver work that activates audiences: to buy, to read, to watch, to engage, to laugh or to cry. I have had a lot of experience managing teams – big and small. I love managing people – I like to motivate them, I enjoy mentoring and the feeling of watching your team reach a satisfying and effective solution is a great one. I get the best out of people. I love entertaining audiences and I believe that comes down to excellent storytelling. I have travelled the world in my role and personal life and found that content that resonates has one thing in common – it means something to people. Whether it is as grand as making their lives better or as simple as starting and ending the day with a smile. -

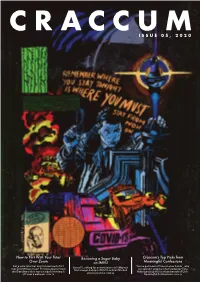

Issue 05, 2020

ISSUE 05, 2020 How to Flirt With Your Tutor Becoming a Sugar Baby Craccum’s Top Picks from Over Zoom on IMVU Meaningful Confessions Got a cute tutor but don’t know how to flirt You’ve got loads of time on your hands - why over Zoom? Never fear! Flirting experts* Cam Bored? Looking for something to do? Why not not spend it judging other students? Tara and Dan share their top ten tips for hitting it find a sugar daddy in IMVU? Lachlan Mitchell Mok rounds up the best (and worst) of UoA: shows you how. PAGE 28 off over a webcam. PAGE 26 Meaningful Confessions. PAGE 30 We can all slow the spread We all need to work together if we want to slow the spread of COVID-19. Unite against the virus now. Be kind. Check-in Washing and Cough or sneeze Stay home on the elderly drying your hands into your elbow if you are sick or vulnerable kills the virus Find out more at Covid19.govt.nz STS_A4_20/03 04 EDITORIAL 06 FROM THE PRESIDENT contents. 06 NEWS 14 Welcome to the End of Days 16 COVID-19 AND OUR UGLY SIDE 18 THE LOCKDOWN CLOWS 21 28 DAYS LATER 26 How to Flirt With Your Tutor Over Zoom 24 REVIEWS 26 IMAGINE NO JOHN LENNON 28 BECOMING A SUGAR BABY ON IMVU 33 How to Tame a Pussy 36 JUST KEEP RUNNING 37 WHO ASKED YOU WANT TO CONTRIBUTE? 38 HOROSCOPES Send your ideas to: NEWS [email protected] FEATURES [email protected] ARTS [email protected] COMMUNITY AND LIFESTYLE [email protected] ILLUSTRATION [email protected] NEED FEEDBACK ON WHAT YOU’RE WORKING ON? [email protected] HOT TIPS ON STORIES [email protected] Your 1 0 0 % s t u d e n t o w n e d u b i q .