Creative Reflections of Pasifika Ethnic Mixedness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT This Copy of the Thesis Has Been

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk 04 University of Plymouth Research Theses 01 Research Theses Main Collection 2012 Life Expansion: Toward an Artistic, Design-Based Theory of the Transhuman / Posthuman Vita-More, Natasha http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/1182 University of Plymouth All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. COPYRIGHT STATEMENT This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognize that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author’s prior consent. 1 Life Expansion: Toward an Artistic, Design-Based Theory of the Transhuman / Posthuman by NATASHA VITA-MORE A thesis submitted to the University of Plymouth in partial fulfillment for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Art & Media Faculty of Arts April 2012 2 Natasha Vita-More Life Expansion: Toward an Artistic, Design-Based Theory of the Transhuman / Posthuman The thesis’ study of life expansion proposes a framework for artistic, design-based approaches concerned with prolonging human life and sustaining personal identity. To delineate the topic: life expansion means increasing the length of time a person is alive and diversifying the matter in which a person exists. -

Art's Histories in Aotearoa New Zealand Jonathan Mane Wheoki

Art’s Histories in Aotearoa New Zealand Jonathan Mane Wheoki This is the text of an illustrated paper presented at ‘Art History's History in Australia and New Zealand’, a joint symposium organised by the Australian Institute of Art History in the University of Melbourne and the Australian and New Zealand Association of Art Historians (AAANZ), held on 28 – 29 August 2010. Responding to a set of questions framed around the ‘state of art history in New Zealand’, this paper reviews the ‘invention’ of a nationalist art history and argues that there can be no coherent, integrated history of art in New Zealand that does not encompass the timeframe of the cultural production of New Zealand’s indigenous Māori, or that of the Pacific nations for which the country is a regional hub, or the burgeoning cultural diversity of an emerging Asia-Pacific nation. On 10 July 2010 I participated in a panel discussion ‘on the state of New Zealand art history.’ This timely event had been initiated by Tina Barton, director of the Adam Art Gallery in the University of Victoria, Wellington, who chaired the discussion among the twelve invited panellists. The host university’s department of art history and art gallery and the University of Canterbury’s art history programme were represented, as were the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, the City Gallery, Wellington, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth, the Dunedin Public Art Gallery and the University of Auckland’s National Institute of Creative Arts and Industries. The University of Auckland’s department of art history1 and the University of Otago’s art history programme were unrepresented, unfortunately, but it is likely that key scholars had been targeted and were unable to attend. -

KANG-THESIS.Pdf (614.4Kb)

Copyright by Jennifer Minsoo Kang 2012 The Thesis Committee for Jennifer Minsoo Kang Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: From Illegal Copying to Licensed Formats: An Overview of Imported Format Flows into Korea 1999-2011 APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Joseph D. Straubhaar Karin G. Wilkins From Illegal Copying to Licensed Formats: An Overview of Imported Format Flows into Korea 1999-2011 by Jennifer Minsoo Kang, B.A.; M.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 Dedication To my family; my parents, sister and brother Abstract From Illegal Copying to Licensed Formats: An Overview of Imported Format Flows into Korea 1999-2011 Jennifer Minsoo Kang, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2012 Supervisor: Joseph D. Straubhaar The format program trade has grown rapidly in the past decade and has become an important part of the global television market. This study aimed to give an understanding of this phenomenon by examining how global formats enter and become incorporated into the national media market through a case study analysis on the Korean format market. Analyses were done to see how the historical background influenced the imported format flows, how the format flows changed after the media liberalization period, and how the format uses changed from illegal copying to partial formats to whole licensed formats. Overall, the results of this study suggest that the global format program flows are different from the whole ‘canned’ program flows because of the adaptation processes, which is a form of hybridity, the formats go through. -

Contemporary Ma¯Ori and Pacific Artists Exploring Place

NZPS 5 (2) pp. 131–143 Intellect Limited 2017 Journal of New Zealand & Pacific Studies Volume 5 Number 2 © 2017 Intellect Ltd Article. English language. doi: 10.1386/nzps.5.2.131_1 Caroline Vercoe University of Auckland Contemporary Ma¯ori and Pacific artists exploring place Abstract Keywords This article explores the notion of ‘place’, extending its scope to include the ocean, Ma-ori art history and diaspora, in relation to six contemporary Ma-ori and Pacific artists who Pacific art were involved in the Pacifique(S) Contemporain exhibitions in Normandy, France contemporary art in 2015. Structured into three sections, it addresses the three curatorial thematics Oceanic identity that provided the overarching frame for the exhibitions. ‘The ocean is a place’ focuses diaspora on Angela Tiatia and Rachael Rakena, and acknowledges the importance of Epeli indigenous Hau’ofa’s writing in relation to the ocean and Oceania as a crucial marker of iden- epistemologies tity both within its geographic location and beyond. ‘History is a place’ considers digital art moving image installations by Michel Tuffery and Greg Semu, in particular referenc- contemporary ing how they rework and reimagine colonial and art historical representations and photography conventions. ‘Diaspora is a place’ compares the photographic practices of Ane Tonga and Edith Amituanai, whose work reflects on and captures the dynamics that emerge as Pacific communities draw on and adapt cultural traditions, and negotiate rela- tionships mediated by their migration and diaspora experiences. Unlike the term ‘site’, the notion of ‘place’ is fluid and multi-layered in its reso- nance. It can define something as particular as a specific location, or could be as broad as a vast area in space. -

Newsletter Principal Mr S V Gargiulo QSO, Bsc, Dip

Manurewa High School Newsletter Principal Mr S V Gargiulo QSO, BSc, Dip. Tchg February 2014 IMPORTANT DATES Dear Parents / Guardians Welcome to new families in our community. The school newsletter, published twice a term, acts as a Saturday 1 March means of connection with Manurewa High School and is one way of remaining informed of events Waka Ama Auckland Champs and student achievement. We are very proud of our achievements in and out of the classroom as you Monday 3 March will read in this newsletter. We do know that having families and community connected to the school Counties/Manukau Swimming is essential to these achievements. Another resource for accessing information is the school website, Champs www.manurewa.school.nz which includes a parent portal – further information on this overleaf. Wednesday 5 March It was great to see so many students make use of the opportunity to return to school early to confirm Mentor and Parents Catch Up, their courses. These students are giving themselves every chance to be able to take courses that will fit MHS Staffroom 6.30pm—8pm their career pathways. Thursday 6 March—Saturday 8 March Volleyball Auckland Champs Manurewa High School commences 2014 on a very positive note with outstanding 2013 NCEA results Saturday 8 March—Sunday 9 March as detailed in the graph below: Ohu and Ohana Yes Groups 2013—Pasifika Festival Auckland Monday 10 March Young Enterprise Eday Tuesday 11 March .Student ID Photos .Fie Fia Night (Tongan) Wednesday 12—Saturday 15 March Polyfest Thursday 13 March Fie Fia Night (Samoan) Friday 14 March STAFF ONLY DAY—Polyfest Friday Monday 17 March STAFF ONLY DAY Sunday 23—Saturday 29 March Summer Tournament Week Wednesday 26 March Production Camp, Willow Park Thursday 27 March While the NCEA results are very encouraging at all levels, I am especially pleased with the Experience Fonterra Day performance of the 2013 Year 11 students who made the most significant improvement and moved the school to above the national average. -

House Resolution

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES THIRTY-FIRST LEGISLATURE, 2021 STATE OF HAWAII HOUSE RESOLUTION REQUESTING THE HAWAII SISTER-STATE COMMITTEE TO EVALUATE AND DEVELOP RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE INITIATION OF A SISTER- STATE RELATIONSHIP WITH THE CITY OF AUCKLAND, NEW ZEALAND. 1 WHEREAS, due to its multicultural population since the days 2 of the Hawaiian Monarchy, Hawaii maintains a heritage of 3 international participation and cultural sensitivity that is 4 unparalleled in other states; and 5 6 WHEREAS, the State actively seeks to expand its 7 international ties and has an abiding interest in developing 8 goodwill, friendship, and economic relations between the people 9 of Hawaii and the people of many nations; and 10 11 WHEREAS, while Hawaii currently maintains eighteen sister- 12 state relationships, none are with any cities or provinces in 13 New Zealand; and 14 15 WHEREAS, Hawaii and New Zealand are part of the triangle of 16 Polynesia, and the indigenous people of Hawaii and New Zealand 17 share many cultural and language similarities; and 18 19 WHEREAS, collaboration with the many Maori and Polynesian 20 cultural institutes in New Zealand would be culturally 21 beneficial to Hawaii; and 22 23 WHEREAS, Hawaii has participated in the Pasifika Festival, 24 an annual Pacific Islands-themed festival typically held in 25 Western Springs, Auckland, New Zealand, since 2014; and 26 27 WHEREAS, New Zealand is consistently ranked as among the 28 top twenty countries for quality of education by the 29 Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development; and 30 31 WHEREAS, as an island nation in the middle of the Pacific 32 Ocean, New Zealand faces some of the same geographic challenges 2021—1961 HR HMSO ~ Page2 H.R. -

Annual Report 2009-2010 PDF 7.6 MB

Report NZ On Air Annual Report for the year ended 30 June 2010 Report 2010 Table of contents He Rarangi Upoko Part 1 Our year No Tenei Tau 2 Highlights Nga Taumata 2 Who we are Ko Matou Noa Enei 4 Chair’s introduction He Kupu Whakataki na te Rangatira 5 Key achievements Nga Tino Hua 6 Television investments: Te Pouaka Whakaata 6 $81 million Innovation 6 Diversity 6 Value for money 8 Radio investments: Te Reo Irirangi 10 $32.8 million Innovation 10 Diversity 10 Value for money 10 Community broadcasting investments: Mahi Whakapaoho a-Iwi 11 $4.3 million Innovation 11 Diversity 11 Value for money 11 Music investments: Te Reo Waiata o Aotearoa 12 $5.5 million Innovation 13 Diversity 14 Value for money 15 Maori broadcasting investments: Mahi Whakapaoho Maori 16 $6.1 million Diversity 16 Digital and archiving investments: Mahi Ipurangi, Mahi Puranga 17 $3.6 million Innovation 17 Value for money 17 Research and consultation Mahi Rangahau 18 Operations Nga Tikanga Whakahaere 19 Governance 19 Management 19 Organisational health and capability 19 Good employer policies 19 Key financial and non financial measures and standards 21 Part 2: Accountability statements He Tauaki Whakahirahira Statement of responsibility 22 Audit report 23 Statement of comprehensive income 24 Statement of financial position 25 Statement of changes in equity 26 Statement of cash flows 27 Notes to the financial statements 28 Statement of service performance 43 Appendices 50 Directory Hei Taki Noa 60 Printed in New Zealand on sustainable paper from Well Managed Forests 1 NZ On Air Annual Report For the year ended 30 June 2010 Part 1 “Lively debate around broadcasting issues continued this year as television in New Zealand marked its 50th birthday and NZ On Air its 21st. -

Post Malone Announces North American Tour with 21 Savage and Special Guest Sob X Rbe

POST MALONE ANNOUNCES NORTH AMERICAN TOUR WITH 21 SAVAGE AND SPECIAL GUEST SOB X RBE Tickets On Sale to General Public Starting Friday, February 23 at LiveNation.com LOS ANGELES, CA (February 20, 2018) – Today, multi-platinum artist Post Malone announced his upcoming North American tour with multi-platinum rapper 21 Savage and special guest SOB X RBE. Produced by Live Nation and sponsored by blu, the outing will kick off April 26 in Portland, OR and make stops in 28 cities across North America including Seattle, Nashville, Toronto, Atlanta, Austin, and more. The tour will wrap in San Francisco, CA on June 24. Tickets will go on sale to the general public starting Friday, February 23 at 10am local time at LiveNation.com. Citi® is the official presale credit card of the Post Malone tour. As such, Citi® cardmembers will have access to purchase presale tickets beginning today, February 20th at 2pm local time until Thursday, February 22nd at 10pm local time through Citi’s Private Pass® program. For complete presale details visit www.citiprivatepass.com. Every pair of online tickets purchased comes with one physical copy of Post Malone’s forthcoming album, Beerbongs & Bentleys. Ticket purchasers will receive an additional email with instructions on how to redeem their album and will be notified at a later date on when they can expect to receive their CD. (U.S. and Canadian residents only.) The history-making Dallas, Texas artist, Post Malone, will also release his new single “Psycho” [feat. Ty Dolla $ign] on Friday February 23, 2018 via Republic Records. -

European Parliament DANZ Report

European Parliament Delegation for relations with Australia and New Zealand (DANZ) visit Auckland and Wellington 23-26 February 2020 Report on the European Parliament’s Delegation for relations with Australia and New Zealand (DANZ) visit 23-26 February 2020 Background The European Parliament’s Delegation for relations with Australia and New Zealand (DANZ) and the New Zealand Parliament have regular exchange meetings. This year it was the turn of DANZ to visit New Zealand for the 24th Inter-parliamentary meeting. As the visit was on a non-sitting week for the New Zealand Parliament, this meeting was held in Auckland to enable easier attendance for New Zealand parliamentarians. This was followed by meetings in Wellington, including with the Speaker of the House of Representatives, three New Zealand Cabinet Ministers and the New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. DANZ’s visit this year was comprised of a larger delegation than usual. Eight members of the European Parliament (MEPs) came to New Zealand, including a Vice President. The members were from five of the six main political groups in the European Parliament – the European People's Party (Christian Democrats), the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament, Renew Europe, the Greens/European Free Alliance and the European Conservatives and Reformists. 1 The DANZ visit was led by Chairperson, Ulrike Müller MEP, who also led the previous delegation to New Zealand in 2018.2 Inter-parliamentary meeting The 2020 meeting was held on Monday 24th February. The New Zealand Members of Parliament who attended are listed at the end of this report. -

Multimorbidity, Clinical Decision Making and Health Care Delivery In

Stokes et al. BMC Family Practice (2017) 18:51 DOI 10.1186/s12875-017-0622-4 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Multimorbidity, clinical decision making and health care delivery in New Zealand Primary care: a qualitative study Tim Stokes1* , Emma Tumilty1, Fiona Doolan-Noble1 and Robin Gauld2 Abstract Background: Multimorbidity is a major issue for primary care. We aimed to explore primary care professionals’ accounts of managing multimorbidity and its impact on clinical decision making and regional health care delivery. Methods: Qualitative interviews with 12 General Practitioners and 4 Primary Care Nurses in New Zealand’s Otago region. Thematic analysis was conducted using the constant comparative method. Results: Primary care professionals encountered challenges in providing care to patients with multimorbidity with respect to both clinical decision making and health care delivery. Clinical decision making occurred in time-limited consultations where the challenges of complexity and inadequacy of single disease guidelines were managed through the use of “satisficing” (care deemed satisfactory and sufficient for a given patient) and sequential consultations utilising relational continuity of care. The New Zealand primary care co-payment funding model was seen as a barrier to the delivery of care as it discourages sequential consultations, a problem only partially addressed through the use of the additional capitation based funding stream of Care Plus. Fragmentation of care also occurred within general practice and across the primary/secondary care interface. Conclusions: These findings highlight specific New Zealand barriers to the delivery of primary care to patients living with multimorbidity. There is a need to develop, implement and nationally evaluate a revised version of Care Plus that takes account of these barriers. -

Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums

28 February 1993 CHART #848 Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums I Will Always Love You Sweet Thing The Bodyguard OST Duophonic 1 Whitney Houston 21 Mick Jagger 1 Various 21 Charles & Eddie Last week 1 / 9 weeks Platinum / BMG Last week 50 / 2 weeks WARNER Last week 1 / 8 weeks Platinum / BMG Last week - / 1 weeks EMI Love Is In The Air Stairway To Heaven Breathless Use Your Illusion I 2 John Paul Young 22 Rolf Harris 2 Kenny G 22 Guns N' Roses Last week 4 / 8 weeks SONY Last week - / 1 weeks POLYGRAM Last week 3 / 6 weeks Gold / BMG Last week 14 / 52 weeks Platinum / BMG New York City Steam Unplugged 3 Years, 5 Months & 2 Days In The Li... 3 Charles & Eddie 23 Peter Gabriel 3 Eric Clapton 23 Arrested Development Last week 2 / 4 weeks EMI Last week 24 / 6 weeks VIRGIN Last week 2 / 23 weeks Platinum / WARNER Last week 32 / 5 weeks EMI You Don't Treat Me No Good You Ain't Thinking (About Me) Live-The Way We Walk-Volume One... Best Of Huey Lewis & The News 4 Sonia Dada 24 Sonia Dada 4 Genesis 24 Huey Lewis & The News Last week 6 / 11 weeks Gold / FESTIVAL Last week 22 / 3 weeks FESTIVAL Last week 7 / 9 weeks Platinum / VIRGIN Last week 37 / 12 weeks Platinum / EMI Please Don't Go Ray Of Shine Cooleyhighharmony What Hits? 5 Boyz II Men 25 JPS Experience 5 Boyz II Men 25 Red Hot Chili Peppers Last week 3 / 5 weeks POLYGRAM Last week - / 1 weeks FESTIVAL Last week 4 / 16 weeks Platinum / POLYGRAM Last week 25 / 15 weeks Platinum / EMI End Of The Road Be Someone / Underground Wandering Spirit Ten 6 Boyz II Men 26 Dead Flowers 6 Mick Jagger 26 Pearl -

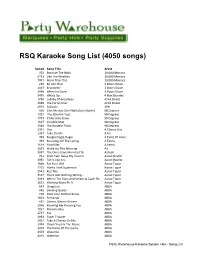

Karaoke 4050 Song List

RSQ Karaoke Song List (4050 songs) Song# Song Title Artist 302 Because The Night 10,000 Maniacs 2133 Like The Weather 10,000 Maniacs 1901 More Than This 10,000 Maniacs 285 Be Like That 3 Doors Down 2047 Kryptonite 3 Doors Down 3446 When Im Gone 3 Doors Down 3435 Whats Up 4 Non Blondes 1798 Lullaby Of Broadway 42nd Street 3089 The Partys Over 42nd Street 2879 Sukiyaki 4PM 866 Give Me Just One Night (Una Noche) 98 Degrees 1201 I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees 1373 If She Only Knew 98 Degrees 1687 Invisible Man 98 Degrees 3046 The Hardest Thing 98 Degrees 2331 One A Chorus Line 2937 Take On Me A Ha 393 Boogie Oogie Oogie A Taste Of Hone 409 Bouncing Off The Ceiling A Teens 1619 Floorfiller A Teens 3563 Woke Up This Morning A3 3087 The One I Gave My Heart To Aaliyah 762 Dont Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville 2951 Tell It Like It Is Aaron Neville 1646 For You I Will Aaron Tippin 1103 Honky Tonk Superman Aaron Tippin 2042 Kiss This Aaron Tippin 3147 There Aint Nothing Wrong... Aaron Tippin 3483 Where The Stars And Stripes & Eagle Fly Aaron Tippin 3572 Working Mans Ph.D. Aaron Tippin 543 Chiquitita ABBA 652 Dancing Queen ABBA 720 Does Your Mother Know ABBA 1603 Fernando ABBA 851 Gimme Gimme Gimme ABBA 2046 Knowing Me Knowing You ABBA 1821 Mamma Mia ABBA 2787 Sos ABBA 2893 Super Trouper ABBA 2921 Take A Chance On Me ABBA 2974 Thank You For The Music ABBA 3078 The Name Of The Game ABBA 3370 Waterloo ABBA 4018 Waterloo ABBA Party Warehouse Karaoke System Hire - Song List Song# Song Title Artist 1660 Four Leaf Clover Abra Moore 2840 Stiff Upper Lip