Contemporary Ma¯Ori and Pacific Artists Exploring Place

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art's Histories in Aotearoa New Zealand Jonathan Mane Wheoki

Art’s Histories in Aotearoa New Zealand Jonathan Mane Wheoki This is the text of an illustrated paper presented at ‘Art History's History in Australia and New Zealand’, a joint symposium organised by the Australian Institute of Art History in the University of Melbourne and the Australian and New Zealand Association of Art Historians (AAANZ), held on 28 – 29 August 2010. Responding to a set of questions framed around the ‘state of art history in New Zealand’, this paper reviews the ‘invention’ of a nationalist art history and argues that there can be no coherent, integrated history of art in New Zealand that does not encompass the timeframe of the cultural production of New Zealand’s indigenous Māori, or that of the Pacific nations for which the country is a regional hub, or the burgeoning cultural diversity of an emerging Asia-Pacific nation. On 10 July 2010 I participated in a panel discussion ‘on the state of New Zealand art history.’ This timely event had been initiated by Tina Barton, director of the Adam Art Gallery in the University of Victoria, Wellington, who chaired the discussion among the twelve invited panellists. The host university’s department of art history and art gallery and the University of Canterbury’s art history programme were represented, as were the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, the City Gallery, Wellington, the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth, the Dunedin Public Art Gallery and the University of Auckland’s National Institute of Creative Arts and Industries. The University of Auckland’s department of art history1 and the University of Otago’s art history programme were unrepresented, unfortunately, but it is likely that key scholars had been targeted and were unable to attend. -

A Visual Arts and Art History Education Resource for Secondary Teachers, Inspired by Bill Culbert's 2013 Venice Biennale Exhi

ART IN CONTEXT A VISUAL ARTS AND ART HISTORY EDUCATION RESOURCE FOR SECONDARY TEACHERS, INSPIRED BY BILL CULBERT’S 2013 VENICE BIENNALE EXHIBITION, FRONT DOOR OUT BACK Helen Lloyd, Senior Educator Art, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa and Education Programme Manager for Creative New Zealand (2013) © Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa and Creative New Zealand, 2013 CONTENTS BaCKGROUND About this resource ............................................................................................. 3 The Venice Biennale ............................................................................................ 4 Venice – the city ................................................................................................... 4 Bill Culbert ............................................................................................................ 5 Front Door Out Back ........................................................................................... 5 Studying art in context ....................................................................................... 6 Curriculum links ................................................................................................... 7 Useful books ........................................................................................................ 7 Useful websites ................................................................................................... 7 RESOURCES Part 1: Front Door Out Back analysis cards Drop ...................................................................................................................... -

Fatu Feu'u School of Fine Arts, University of Auck1;Md Selected Biography Specifically Pacific

Fatu Feu'u School of Fine Arts, University of Auck1;md Selected Biography Specifically Pacific. group exhibition, Massey I-Iomestead 1946 Born POlltllsi Falealili, Western Samoa Pacific Riwal M{/.~h, solo exhibition, Lopdel1 House. 1966 Emigrated to New Zealand Auckland 1983 Mtll1akal/ Series I ,solo exhibition, Massey Homestead SOllgs ofthe Earlh, group exhibition. Hastings Arts 1984 Spill/ling Fromier, solo exhibition, Gallery Pacific, Centre Auckland Coroll/andei Callill/:, group exhibition. OUlreach Mal/aka/{ Series 1/, solo exhibition, MllSsey Gllilery, Auckland Homestead Book cover design. A Simplified Dictionary of Modem SOIl/Olll/, Polynesian Press, Auckland 1986 Lilhograp!ls, solo exhibition, Samoa House, Auckland Assistant painlcr, Auckland University Martie Solo ofe LI/pe. solo exhibition. Muk<l Studio, Auckland 1987 Book cover design, Tala () Ie \llilall: Ihe M)'Ih.~. Legel/ds alld Clls/oms o!Old Samoa. Polynesian Press. Auckland Oil PailllillgslTapa Motif,f. solo exhibition. Samoa House. Auckland SI3cey,G.. 'The Art of Fatu Feu'u'. AI'! Nell' Zealand, no.45. pp 48-51 1988 Artist in Residence. Elam School of Fine Arts. University of Auckland New Oil Paill/il/gs, solo exhibition, TaUlai Gallery, Auckland Lilhograpl1,f, Dowse Art Museum, Lower HUll Director, Talllai Gallery. Auckland Art tlllor, Manakllu Polytechnic Mililllillli, 1990 Woodcllt.~. solo exhibition, Massey Homestead Commission for paintings, Papakura Church New Zealand £.\1'0 '88. Brisbane, Australia FalU Feu'u's images arc derived from the mythologies and Group exhibition, Frans Maserell Centrum, Belgium ancient legends of S;Jllloa and the Pacific. Using traditional Book cover design, Cagna Sall1o(/, A Samoan motifs and forms from the visual resources of Polynesia, the La/lgllt/ge COllrselJook, Polynesian Press, arts ofsiapo painting on wpa cloth, Ill/au (tattooing), carving, Auckland ceremonial mllsk making, and Lapila poHery from early Pacific Masks, Massey Homeste;ld Samoa,Feu'u employs a vocabulary charged wilh symbolic Paciric Masks Workshop. -

Cloud of Kiwi in Cartoons and Graphic Novels, Words in Speech Or Thought Bubbles Hang Above the Character’S Head Like a Cloud

Cloud of Kiwi In cartoons and graphic novels, words in speech or thought bubbles hang above the character’s head like a cloud. This artwork is one great big cloud of thousands of words. The work by artist John Reynolds soil, corner dairy, puku, no-hoper. is called Cloud. It’s made of 7081 They’re all part of the English that individual canvas panels, each of them people in New Zealand speak. John Reynolds is painted with a word or phrase that ‘John Reynolds has always widely considered to be comes from the Oxford Dictionary of worked with language in his art,’ says one of fi nest artists New Zealand English – for example, curator Charlotte Huddleston. ‘He in New Zealand, with work held in all of this tin-arse, tough bickies, waka, pumice likes to play with words and he’s had a country’s major private and public collections. 8 English long fascination with the Dictionary ‘It took a team of five or six of New Zealand English.’ people six days altogether to install Reynolds created the work to Cloud at Te Papa,’ says Charlotte. reflect Aotearoa’s connection to ‘John was here, of course, leading the community of English-speaking the charge. We designed a special nations. At the same time he wanted storage system for it as well, with to highlight what is local and regional twelve canvases in a tray, five trays about the English that people in this in a box and a total of 125 boxes in a country speak. crate. All the parts are numbered and He arranged the words to create catalogued so we know where every the feeling of a billowing, condensing single word or phrase is.’ It’s made of 7081 individual canvas panels, each of them painted with a word or phrase. -

Download Download

eTropic: electronic journal of studies in the tropics Repurposing, Recycling, Revisioning: Pacific Arts and the (Post)colonial Jean Anderson https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3280-3225 Te Herenga Waka - Victoria University of Wellington, Aotearoa/New Zealand Abstract Taking a broad approach to the concept of recycling, I refer to a range of works, from sculpture to film, street art and poetry, which depict issues of importance to Indigenous peoples faced with the (after) effects of colonisation. Does the use of repurposed materials and/or the knowledge that these objects are the work of Indigenous creators change the way we respond to these works, and if so, how? Keywords: Pacific artists, food colonisation, reappropriation, speaking back, culture eTropic: electronic journal of studies in the tropics publishes new research from arts, humanities, social sciences and allied fields on the variety and interrelatedness of nature, culture, and society in the tropics. Published by James Cook University, a leading research institution on critical issues facing the worlds’ Tropics. Free open access, Scopus, Google Scholar, DOAJ, Crossref, Ulrich's, SHERPA/RoMEO, Pandora, ISSN 1448-2940. Creative Commons CC BY 4.0. Articles are free to download, save and reproduce. Citation: to cite this article include Author(s), title, eTropic, volume, issue, year, pages and DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.25120/etropic.19.1.2020.3733 eTropic 19.1 (2020) Special Issue: ‘Environmental Artistic Practices and Indigeneity’ 186 Introduction his study takes a broad view of recycling, looking at examples from a range of forms of artistic expression, to explore ways in which Indigenous artists in the T Pacific make use of repurposed materials to criticise some of the profoundly unsettling – and enduring – effects of colonisation. -

Creative Reflections of Pasifika Ethnic Mixedness

‘The Bitter Sweetness of the Space Between’: Creative Reflections of Pasifika Ethnic Mixedness By Emily Fatu A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Pacific Studies Pacific Studies, Va‘aomanū Pasifika Victoria University 2016 Abstract This Master of Arts thesis investigates and draws conclusions regarding how creative arts present accommodating spaces for articulating and understanding cultural mixedness amongst Pacific populations in New Zealand. New Zealand is home to an expanding Pacific population; statistics identify a growing number of these Pacific people who are multi-ethnic, and who are claiming their mixedness in official census data. As Pacific populations have grown, Pacific artists have risen to national prominence in visual, literary and performing arts. Many of these artists have themselves been of mixed ancestry. This thesis examines the work of three female New Zealand artists of mixed Samoan-English or Samoan- Indian descent, asking, “How do these artists and their work express their cultural mixedness?” Discussion centres on mixed media visual artist Niki Hastings-McFall, who is of English and Samoan descent; spoken word poet Grace Taylor, also of English and Samoan descent; and musical performer Aaradhna Patel, who is of Indian and Samoan descent. Placing both the creative work and public commentary of these three artists at its centre, this thesis explores how these artists publicly identify with their Samoan heritage as well as their other heritage(s); how they use their art as a platform for identity articulation; and how creative arts provide flexible and important spaces for self-expression. -

Michel Tuffery

M ICHEL TUFFERY S IAMANI SAMOA J EM 1809 PARRAMATTA SHEEP KNIFE—TASI (2008) Kauri wood, Svord steel blade, bronze 6 x 4 x 35 cm $3,300 J EM 1809 PARRAMATTA SHEEP KNIFE—LUA (2008) Rimu wood, Svord steel blade, bronze 6 x 4 x 35 cm $3,300 S IAMANI KOKOSNÜSSE PLANTATION AT MULINU' U (2011) Rimu wood, black acrylic or pink acrylic (Edition 50) 41 x 13 cm $275 L UA MANUMEA AT SIAMANI KOKOSNÜSSE PLANTATION (2011) Rimu wood, black acrylic or pink acrylic (Edition 50) 30 x 25 cm $275 N UI SIAMANI SAMOA (2011) Rimu wood, black acrylic or pink acrylic (Edition 50) 28 x 23 cm $275 M ULINU' U TO BERLIN 1900 (2011) Rimu wood, black acrylic or pink acrylic (Edition 50) 30 x 18 cm $275 TAVA' E MA LE LUA SOLOFANUA AT BRANDENBURG GATE BERLIN (2011) Rimu wood, black acrylic or pink acrylic (Edition 50) 29 x 28 cm $275 VAILELE SIAMANI KOKOSNÜSSE PLANTATION (2011) Rimu wood, black acrylic or pink acrylic (Edition 50) 41 x 9 cm $275 C ATHOLIC CATHEDRAL, MULIVAI, APIA, SAMOA (2011) Rimu wood, black acrylic or pink acrylic (Edition 50) 35 x 11 cm $275 M ANUMEA—TOOTHBILL PIGEON (2011) Rimu wood, black acrylic or pink acrylic (Edition 50) 30 x 22 cm $275 T HE COURT HAUS, APIA SAMOA (2011) Rimu wood, black acrylic or pink acrylic (Edition 50) 37 x 15 cm $275 C OCO WITH KOKO SAMOA AT THE ORIGINAL GERMAN TRADING BUILDING ON BEACH ROAD, A PIA, 2010 (2011) Rimu wood, black acrylic or pink acrylic (Edition 50) 30 x 31 cm $275 M ULINU' U TO BERLIN, TAMASESE AND DR WILHELM SOLF OFF TO VISIT THE KAISER (2011) Acrylic on canvas 66 x 91 cm $12,500 S IAMANI SAMOA HOSPITAL, -

Michel Tuffery Te Moana Nui a Kiwa 4Th February – 7Th March 2021

Old Library Building Phone 03 366 3318 The Arts Centre Email [email protected] 2 Worcester Boulevard www.thecentral.co.nz Christchurch Michel Tuffery Te Moana Nui a Kiwa 4th February – 7th March 2021 Star Compass for Matariki, 2021 Te Moana Nui a Kiwa, 2021 In 2020, Michel Tuffery collaborated with Dr Karlo Mila to create the narrated and animated video Mana Moana 2020 Meditation playing on our east wall. This exhibition emerges from this co-creation, and from origins as ancient as the great sea of Kiwa. Seven new works share stories of unfurling life and ongoing whakapapa, the unbreakable connections of past-present-future and ocean-land-sky. Prompted by stills from the meditation, each work has been hand-drawn, extended and reinvigorated at extraordinary resolution. Compulsory Covid-19 lockdowns gave time and pause for Tuffery to harness new creative and printing technologies. Details emerge from the blackest of black inks as though luminescent. The distinction between 2-d and 3-d cannot hold; these works pulsate, twinkle and spin. Reaching out from the fertile darkness of the realm of potential being, here is our ever-turning world. Michel Tuffery warmly acknowledgements Dr Karlo Mila and the Mana Moana Cutarorial Aiga; Rachel Rakena, Michael Bridgman, Storybox, Manase Lua, Laughton Kura, Dr Billie Lythberg and CNZ. www.manamoana.co.nz/artwork/mana-moana-meditation/ Old Library Building Phone 03 366 3318 The Arts Centre Email [email protected] 2 Worcester Boulevard www.thecentral.co.nz Christchurch All works are drawing, pigment inks on Hahnemühle Photorag 308 Cotton Paper. -

Art of Samoa

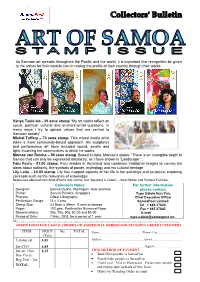

As Samoan art spreads throughout the Pacific and the world, it is important that recognition be given to the artists for their contribution in raising the profile of their country through their works. Vanya Taule'alo - 25 sene stamp “My art works reflect on social, political, cultural and environmental questions. In many ways I try to uphold values that are central to Samoan society” Michel Tuffery – 70 sene stamp. This mixed media artist takes a more community-based approach. His sculptures and performance art have included sound, smells and light, involving the communities in which he works. Momoe von Reiche – 90 sene stamp. Based in Apia, Momoe‟s states: “There is an intangible depth to Samoa that can only be expressed abstractly, as I have shown in 'Landscape' “. Fatu Feu'u - $1.00 stamp. Fatu resides in Auckland and combines traditional images to convey his ideas about authority, the symbols of power, mythology and his cultural heritage Lily Laita - $4.00 stamp. Lily has mapped aspects of her life in her paintings and sculpture, exploring concepts such as the relevance of knowledge. References obtained from Artok (Pacific Arts Online) and „Speaking in Colour” – Sean Mallon and Pandora Fulimalo . Collectors Notes: For further information Designer: Denise Durkin, Wellington, New Zealand please contact: Printer: Secura Printers, Singapore Tupe Ualolo Nun Yan, Process: Offset Lithography Chief Executive Officer Perforation Gauge: 13 x 2 cms. SamoaPost Limited Stamp Size: 24.5mm x 39mm, 5 vertical stamps Tel. + 685 27640, Paper: 102 gsm, Postmaster Gummed Paper Fax + 685 27643 Denominations: 25s, 70s, 90s, $1.00 and $4.00 E mail Period of Sale: 7 May, 2003, for a period of 1 year. -

TUPAIA: PALINGENESIS of a POLYNESIAN EPIC HERO Elena Traina Independent Researcher

TUPAIA: PALINGENESIS OF A POLYNESIAN EPIC HERO Elena Traina Independent Researcher RIASSUNTO: Nel 1769, il navigatore polinesiano Tupaia salì a bordo della Endeavour, capitanata da James Cook, assumendo il ruolo di intermediario culturale e interprete nei primi incontri tra europei e Māori su Aotearoa (Nuova Zelanda). Ciò che sappiamo di Tupaia si deduce dai diversi resoconti stilati dai membri britannici della spedizione, mentre non sono sopravvissute fonti Māori o polinesiane dalla sua morte nel 1770. In occasione delle celebrazioni “Tuia 250” nel 2019, la storia di Tupaia fu ripresa dalla poetessa Courtney Sina Meredith e dall’illustratore Mat Tait in The Adventures of Tupaia, una graphic novel che accosta dati storici e aneddoti con interpretazioni narrative di alcuni aspetti della sua vita. Nello stesso anno, la regista Lala Rolls terminava di produrre un’altra opera artistica volta a reinterpretare la vita di Tupaia, il documentario Tupaia’s Endeavour (2020). Questa ricerca si propone di interpretare queste due opere come segni di un processo di palingenesi di Tupaia come eroe epico, e di ricostruire la sua identità eroica tramite temi e aspetti in comune tra la graphic novel e il film. PAROLE CHIAVE: Tupaia, Polinesia, heroo-poiesis, palingenesi, epica mancante ABSTRACT: Polynesian navigator Tupaia boarded Captain Cook’s Endeavour in Tahiti in 1769, becoming a cultural intermediary and interpreter during the first encounters with the Māori people in Aotearoa. What we know of Tupaia is gathered by several accounts by members of the British expedition, but no Māori or other Polynesian sources have survived after Tupaia’s death in 1770. As part of New Zealand’s “Tuia 250” commemoration in 2019, Tupaia’s story was retold by poet Courtney Sina Meredith and illustrator Mat Tait in The Adventures of Tupaia, a graphic novel which combines historical facts and anecdotes with fictional interpretations of some aspects of Tupaia’s life. -

Dedication of Te Reo Hotunui O Te Moana Nui a Kiwa PACIFIC ISLANDS MEMORIAL

Dedication of Te Reo Hotunui o Te Moana Nui a Kiwa PACIFIC ISLANDS MEMORIAL Pukeahu National War Memorial Park Saturday 27 March 2021 Contents Message from the Prime Minister of New Zealand 4 New Zealand’s military links with the Pacific 6 Order of Ceremony 12 About the Memorial 16 WHAKAAHUATIA A KONEI KIA MAU TŌ TORONGA MAI I TE NZ COVID TRACER APP SCAN HERE TO SIGN-IN WITH THE NZ COVID TRACER APP PUKEAHU NATIONAL WAR MEMORIAL PARK Message from the Prime Minister of New Zealand setting of the Pukeahu National War Memorial Park. The name of their design, Te Reo Hotunui o Te Moana nui a Kiwa – The deep sigh of the Pacific, perfectly encapsulates the symbolism of this memorial. Pacific peoples served with great courage and spirit, despite facing many additional hardships in their service, particularly during the First World War - including language barriers, and the extreme toll that exposure to foreign disease and illness took. Kia ora koutou. Their sacrifice must be shared, We gather today for the dedication of Te understood and never forgotten. Reo Hotunui o Te Moana Nui a Kiwa, the Pacific Islands Memorial. This historic Our bonds with the Pacific today span event was due to take place in April last culture, history, people, and language. year, making today’s dedication all the The Pacific Islands Memorial recognises more special. those connections, strengthening our relationships into the future. The Pacific Islands Memorial recognises the unique bond between Aotearoa New Zealand and the Pacific Islands, and acknowledges the service and sacrifice of Pacific peoples in the First and Second World Wars, and in Rt Hon Jacinda Ardern subsequent conflicts around the world. -

1St Project Funding Round 2002/2003

Creative New Zealand Funding 1ST PROJECT FUNDING ROUND 2002/2003 This is a complete list of project grants offered in the first funding round for the 2002-2003 year. Grants are listed within artforms under Creative New Zealand funding programmes. In this round, 281 project grants totalling more than $3.72 million were offered to artists and arts organisations. More than $14.35 million was requested from 847 applications. Arts Board: Creative & Sean MacDonald: towards study in New York International Institute of Modern Letters: to $5,000 support the second issue of “Best New Zealand Professional Development Poems” on line Touch Compass Dance Trust: towards research $3,000 CRAFT and development of a site-specific work Australian Centre For Craft & Design: towards $15,176 JAAM: towards the publication of two issues in research for a New Zealand exhibition in 2003 Australia FINE ARTS $3,500 $4,000 Asia Society: towards the curatorial development of an exhibition on New Zealand and Pacific New Zealand Society Of Authors: to support its Steph Lusted: towards tertiary study in Germany Islands art in New York annual programme of activity $5,000 $25,000 $46,000 Northland Craft Trust: towards the 2003 Alison Bramwell: towards a sculpture symposium Peppercorn Press: to support the publication of summer school at the Quarry in Takaka five issues of “New Zealand Books” $10,325 $14,000 $23,000 New Zealand Society of Potters: towards a Emily Cormack: towards a curatorial internship Sport: to support the publication of two issues in programme of touring