Influence in an Age of Terror: a Framework of Response to Islamis Influence in an Age of Terror 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kult-Duo Geht Ins Finale

9.1. - 15.1.2020 ABSCHIEDSPROGRAMM VON SPITZ & STUMPF KAISERSLAUTERN Mark Forster ZWEIBRÜCKEN Kult-Duo Patric Heizmann LUDWIGSHAFEN i e r f / k c u r d s Hochzeitsmesse e r d n e A : geht ins Finale o t o F SONNTAGS-BRUNCH am 26. Januar Große AuswahlanKöstlichkeiten –und für nur18,50 Euro ist für alleGeschmäcker etwas dabei. Schlemmen Sie bei unsvon 10:00 bis14:30Uhr.Vorbestellung erforderlich! Altstadtplatz15•67071 Ludwigshafen-Oggersheim Tel. 0621 67180582 •[email protected] www.zur-alten-turnhalle.de HUNGER? 10359244_10_1 MAIKAMMER SEITE 13 ! KULTUbR.2020 Trio l Adam Marce 10361827_20_12 13. RHEIN-NECKAR HANDMADE- & KREATIVMARKT 11./12.1. Sa./So.11-18 Uhr, Heddesheim, Nordbadenhalle, Eintritt: 4,-/3,50 € www.kreativ.events 10381411_10_1 Seit Kältetechnik DasGasthausGöres sagt Dankezuallen 70 Jahren Gästen,die unsamWannerschdach 2019 WEGERICH Tel. 06232-33431 besuchthaben sowieein großes oder 06344-9442332 Freitag,17. Januar 2020, 20 Uhr (Einlass: 19.30 Uhr) Dankeschön an dieHelfer undwünscht www.kaeltetechnik-wegerich.de BürgerhausMaikammer allenein gutesneues Jahr. Beratung -Meisterbetrieb Klimaanlagen für jeden Bedarf 67487Maikammer,Marktstraße 8 Kühlhäuser/-zellen • Gastronomiekühlungen Eintritt: 18,00 € BärbelGöres – GasthausGöres Kartenvorverkauf über www.ticket-regional.de und allen angeschlossenen Vorverkaufsstellen, u.a. bei: Büro für Tourismus Maikammer,Johannes-Damm-Straße 11,67487 Maikammer Jetzt in Harthausen Schreibwaren Pfeiffer,Weinstraße Nord37, 67487Maikammer, Media Markt Neustadt, Chemnitzer Straße 33, 67433 Neustadt an der Weinstraße, 10375628_20_3 Tabak-Weiss, Hauptstraße 61,67433 Neustadt an der Weinstraße, Büro für Tourismus, Marktstraße 50, 76829 Landau, Lutz Tickets und Event Service, Wormser Straße 22a, 67346 Speyer 10364740_10_1 10378088_20_1 L E O 9 . 1 . 2 0 D I E S E W O C H E SE IT E 3 A Zwei Klappstühle, .. -

Inside the 'Hermit Kingdom'

GULF TIMES time out MONDAY, AUGUST 10, 2009 Inside the ‘Hermit Kingdom’ A special report on North Korea. P2-3 time out • Monday, August 10, 2009 • Page 3 widespread human rights abuses, to the South Korean news agency Traffi c lights are in place, but rarely is a luxury. although many of their accounts Yonhap, he has described himself as used. North Korea has a long history of inside date back to the 1990s. an Internet expert. Pyongyang’s eight cinemas are tense relations with other regional According to a report from the He is thought to have fi nally said to be frequently closed due powers and the West — particularly UN High Commission for Human annointed the youngest of his three to lack of power; when open, they since it began its nuclear Rights this year: “The UN General sons Kim Jong-un as his heir and screen domestic propaganda movies programme. China is regarded Assembly has recognised and “Brilliant Comrade”, following with inspiring titles such as The Fate as almost its sole ally; even so, condemned severe Democratic his reported stroke last year. Even of a Self-Defence Corps Man. relations are fraught, based as much People’s Republic of Korea human less is known about this leader- The state news agency KCNA as anything on China’s fear that rights violations including the in-waiting. Educated in Bern, runs a curious combination of brief the collapse of the current regime use of torture, public executions, Switzerland, the 25-year-old is said news items such as its coverage of could lead to a fl ood of refugees and extrajudicial and arbitrary to be a basketball fan. -

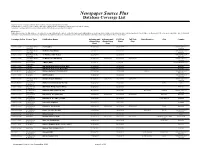

Newspaper Source Plus Database Coverage List

Newspaper Source Plus Database Coverage List "Cover-to-Cover" coverage refers to sources where content is provided in its entirety "All Staff Articles" refers to sources where only articles written by the newspaper’s staff are provided in their entirety "Selective" coverage refers to sources where certain staff articles are selected for inclusion Please Note: Publications included on this database are subject to change without notice due to contractual agreements with publishers. Coverage dates shown are the intended dates only and may not yet match those on the product. All coverage is cumulative. Due to third party ownership of full text, EBSCO Information Services is dependent on publisher publication schedules (and in some cases embargo periods) in order to produce full text on its products. Coverage Policy Source Type Publication Name Indexing and Indexing and Full Text Full Text State/Province City Country Abstracting Abstracting Start Stop Start Stop Cover-to-Cover TV & Radio News 20/20 (ABC) 01/01/2006 01/01/2006 United States of Transcript America Cover-to-Cover TV & Radio News 48 Hours (CBS News) 12/01/2000 12/01/2000 United States of Transcript America Cover-to-Cover TV & Radio News 60 Minutes (CBS News) 11/26/2000 11/26/2000 United States of Transcript America Cover-to-Cover TV & Radio News 60 Minutes II (CBS News) 11/28/2000 06/29/2005 11/28/2000 06/29/2005 United States of Transcript America Cover-to-Cover International 7 Days (UAE) 11/15/2010 11/15/2010 United Arab Emirates Newspaper Cover-to-Cover Newswire AAP Australian National News Wire 09/13/2003 09/13/2003 Australia Cover-to-Cover Newswire AAP Australian Sports News Wire 10/25/2000 10/25/2000 Australia All Staff Articles U.S. -

30 Jahre Mauerfall

FERNSEHEN 14 Tage TV-Programm 31.10. bis 13.11. Diverse Sendungen zum runden Jubiläum 30 Jahre Mauerfall Berliner Blau Im hohen Gras / Rhea M... Feature im Kulturradio über eine Farbe, die Zwei Stephen King-Verilmungen, auf Uniformen und Tassen Karriere machte eine bei Netlix, eine als Mediabook tv-heft Heft_001 1 17.10.19 16:39 Fernsehen 31.10. – 13.11. Gesangseinlage KOMMENTAR VOM TELEVISOR Selber singen fördert die Gesund- heit, da sind sich Experten einig. Wenig erforscht sind bislang die Folgen des Konsums von Gesangsshows, die derzeit eine Art Renaissance feiern. Im Sommer sorgte „The Masked Singer“ für schräge Auftritte von zunächst anonymen Stars in Ganzkörperkostümen von Astronaut bis Schmetterling. Eine zweite Staffel ist bereits geordert. Jetzt geht die neunte Staffel von „The Noch nicht ganz weg – aber so gut wie: Die Mauer 1989 Voice of Germany“ auf die Zielgerade, Finale ist mit dem 10. November der Tag nach dem Mauerfall. Der ja eigentlich ein Anlass sein könnte, mal wieder aus Wem die Wende schlägt dem Stehgreif zusammen zu singen wie Schaue TV-Sendungen zum 30. Jubiläum des Mauerfalls einst die Bundestagsabgeordneten, die am 9. November 1989 spontan die Na- Am 9. November 1989 verzettelte sich Freude und Eierkuchen protestieren, gilt tionalhymne anstimmten. Die muss es Günter Schabowski als Sekretär für (Des) der friedliche, doch freudlose Protest im vielleicht nicht sein angesichts aller Ost- Informationswesen der DDR, als er um Osten den Eierköpfen aus dem Politbüro West- und Genderdebatten der letzten 18.53 Uhr das Inkrafttreten zur Neurege- - Wahlbetrug bei den Kommunalwahlen Jahre um das Haydn-Fallersleben-Tradi- lung von Westreisen „unverzüglich“ nann- heißt der Vorwurf. -

2011 State of the News Media Report

Overview By Tom Rosenstiel and Amy Mitchell of the Project for Excellence in Journalism By several measures, the state of the American news media improved in 2010. After two dreadful years, most sectors of the industry saw revenue begin to recover. With some notable exceptions, cutbacks in newsrooms eased. And while still more talk than action, some experiments with new revenue models began to show signs of blossoming. Among the major sectors, only newspapers suffered continued revenue declines last year—an unmistakable sign that the structural economic problems facing newspapers are more severe than those of other media. When the final tallies are in, we estimate 1,000 to 1,500 more newsroom jobs will have been lost—meaning newspaper newsrooms are 30% smaller than in 2000. Beneath all this, however, a more fundamental challenge to journalism became clearer in the last year. The biggest issue ahead may not be lack of audience or even lack of new revenue experiments. It may be that in the digital realm the news industry is no longer in control of its own future. News organizations — old and new — still produce most of the content audiences consume. But each technological advance has added a new layer of complexity—and a new set of players—in connecting that content to consumers and advertisers. In the digital space, the organizations that produce the news increasingly rely on independent networks to sell their ads. They depend on aggregators (such as Google) and social networks (such as Facebook) to bring them a substantial portion of their audience. And now, as news consumption becomes more mobile, news companies must follow the rules of device makers (such as Apple) and software developers (Google again) to deliver their content. -

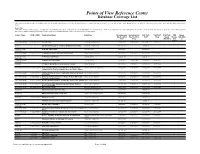

Points of View Reference Center Database Coverage List

Points of View Reference Center Database Coverage List *Titles with 'Coming Soon' in the Availability column indicate that this publication was recently added to the database and therefore few or no articles are currently available. If the ‡ symbol is present, it indicates that 10% or more of the articles from this publication may not contain full text because the publisher is not the rights holder. Please Note: Publications included on this database are subject to change without notice due to contractual agreements with publishers. Coverage dates shown are the intended dates only and may not yet match those on the product. All coverage is cumulative. Due to third party ownership of full text, EBSCO Information Services is dependent on publisher publication schedules (and in some cases embargo periods) in order to produce full text on its products. Source Type ISSN / ISBN Publication Name Publisher Indexing and Indexing and Full Text Full Text Full Text PDF Image Abstracting Abstracting Start Stop Delay Images QuickVie Start Stop (Months) (full w page) Book / Monograph 9780761324065 2000 Election Lerner Publishing Group 01/01/2003 01/31/2003 01/01/2003 01/31/2003 Speech 3rd Annual Message to Congress (Franklin Roosevelt) Great Neck Publishing 01/01/2009 01/01/2009 TV & Radio News 48 Hours (CBS News) CQ Roll Call Inc. 12/01/2000 12/01/2000 Transcript Book / Monograph 9780761316121 50 American Heroes Every Kid Should Meet Lerner Publishing Group 01/01/2002 01/31/2002 01/01/2002 01/31/2002 TV & Radio News 60 Minutes (CBS News) CQ Roll Call Inc. -

Mad for the Mobile Living Multiple Lives with Cambodia’S Latest Phone Fad

NOT FOR SALE your essential lifestyle liftout with seven days Tv Guide THE PHNOM PENH POST - SEPTEMBER 4 -10, 2009. ISSUE 6 SEVENdays MARKET FORCES What happens when men and markets mingle Mad for the Mobile Living multiple lives with Cambodia’s latest phone fad Fashion • Food & drink • Travel • healTh • sTyle • WhaT’s on • sTuFF 2 INSIDE THE PHNOM PENH POST 7DAYS SEPteMbeR 4 -10, 2009 03 WHAT'S ON Your guide to the seven days ahead 14 8 05 HEALTH & BEAUTY What’s good for you 06 FASHION Bag it up – and stay in style 08 OFF THE GRAPEVINE Reporting from the swaying frontline of the wine industry 11 SIEM REAP SCENE 16 Explore the mysteries of the tamarind 14 FEATURE Dial into local mobile phone culture 16 COVER StoRY Hunting the weird and wonderful in Phnom Penh’s markets 19 TRAVEL Post Media Ltd CEO: Michel Dauguet Post Media Ltd. Learn to be budget-conscious on the road Publisher: Ross Dunkley Level 8, No 888 Building F, Editor: Joel Quenby The Phnom Penh Centre, Cnr Sothearos St and Sihanouk Blvd, Deputy Editor: Mark Roy Phnom Penh Cambodia. Subeditor: Dene Mullen 20 TV GUIDE Designer: Andy Ball Be an informed channel-hopper Fashion Editor: Maya Ballard-Downs Telephone 855 23 214 311 Reporters: Mom Ou, Roth Meas Facsimile 855 23 214 318 Layout: Tun Min Soe Email [email protected] 31 ON THE SCENE If you see one of our resident snappers, say © Copyright Post Media Limited The title 7Days , in either English or Khmer languages, its associated logos or devices and the contents of this publication may not be reproduced camembert! in whole or in part without the written consent of Post Media Limited. -

Haber Kanali Olgusu Ve Yayin Politikasi Ilişkisi

TC. İstanbul Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Radyo Televizyon ve Sinema Anabilim Dalı Yüksek Lisans Tezi HABER KANALI OLGUSU VE YAYIN POLİTİKASI İLİŞKİSİ Naime Çetin 2501060604 Tez Danışmanı Prof. Dr. Neşe Kars İSTANBUL 2009 I II Haber Kanalı Olgusu Ve Yayın Politikası İlişkisi Naime ÇETİN ÖZ Televizyon yayıncılığın da tematik haber kanallarının hızla artış göstermesi ‘haber’ kavramı ve ‘televizyon haberciliği’ anlayışlarının faklılaşmasını da beraberinde getirmiştir. Bu araştırma, ‘haber kanalı’ olgusunun ne olması gerektiği ve var olanların bu oluşuma uyup uymadıklarının kaygısından yola çıkmıştır. “Haber kanalı olgusu ve yayın politikası ilişkisi” adlı bu çalışmayla, haber kanalları yöneticilerinin yayın politikaları doğrultusunda ‘haber kavramı’ içerisinde izleyiciye ne sunduğu, yayın akışları içerisinde hangi tür programlara yer verdikleri ve habere ne kadar yer ayırdıkları sorgulanmıştır. Bu amaç doğrultusunda Türkiye’de yayın yapan NTV, CNN TÜRK, SKYTURK, HABER TURK, TRT2, TGRT HABER, HABER 7 (Ülke Tv) yöneticileri ve önde gelen uluslar arası haber kanalları BBC WORLD NEWS ve CNN INTERNATIONAL yöneticileriyle ile yüz yüze veya yazılı iletişim teknikleri kullanılarak derinlemesine mülakat yapılmıştır. Medya yöneticilerinin haber anlayışları çerçevesinde haber kanallarının yayın politikaları ortaya çıkarılmaya çalışılmıştır. Niteliksel görüşme ve niceliksel yayın akışı içerik çözümlemesi yöntemlerinin uygulandığı bu çalışmada, çalışma evreni içerisindeki haber kanallarının yayın akışları karşılaştırılarak haber kanallarında izleyiciye tüm gün boyunca hangi tür programların iletildiği tespit edilmiştir. Anahtar kelimeler: Tematik kanal, yayın politikası, haber kanalı ABSTRACT Understanding of the concept of thematic broadcasting brings a differentiation among understanding of ‘News’ and ‘TV Journalism’. Starting point of this study is analyzing and questioning of the News Channel Format and also interrogating major News broadcasters if they conform with the values. -

Sunday Morning Grid 9/28/08 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/28/08 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 am 8 am 8:30 am 9 am 9:30 am 10 am 10:30 am 11 am 11:30 am Noon 12:30 pm 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face Nation NFL Today Å Paid Program Dog Tales Animal R. Mountain Biking 4 NBC Today in L.A.: Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Matthews News LXTV PGA Tour Golf The Tour Championship Final Round. Å 5CW Paid Believers Paid Joel Osteen Paid Changing Shook Paid Program Ed Young Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week With George News (N) Å NASCAR Countdown NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Camping World RV 400. 9 KCAL In Touch-Dr Conley Paid It Is Written Paid Hour of Power (N) (TVG) Paid Program Think Blue 11 FOX News Fox News Sunday Fox NFL Sunday Å Football Green Bay Packers at Tampa Bay Buccaneers. Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Hr./Hope Christian Faith Phil Blazer Paid Program Iranian TV (In Farsi) Jaam-E-Jaam (In Farsi) 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR WordWorld Cartoon Painting Oil Painting Watercolor Art Work Made-Spain Martin Yan Test Kitch Gourmet New York Primal Grill 28 KCET Sesame Street (N) (TVY) Animalia Raggs Mr Rogers Berenstain Signing Sid Nature Raptor Force. SoCal Place 30 ION Turning Pt Discovery In Touch-Dr Paid Program Inspiration Ministry Campmeeting David Cerullo. 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto Fútbol de la Liga Mexicana Toluca vs. Santos. -

Die Bushaltestelle Des Grauens

FERNSEHEN 14 Tage TV-Programm . bis 20.. „Warten auf’n Bus“ in der rbb-Mediathek Die Bushaltestelle des Grauens Karpfen angeln Deutscher Feature über ein Kindheitstrauma durch Was wäre, wenn eine rechte Partei an die modrige Fische im Kulturradio Macht käme? Miniserie bei ZDFneo tipTV_1020_01_Cover.indd 1 30.04.20 22:31 Fernsehen 7. – 20.5. Blaise Pascal und das Fernsehzimmer der Isolation KOMMENTAR VOM TELEVISOR Aha, soso, die Art und Weise, wie der Televisor seit Jahren lebt, nennt man also Kwahrannteene (o.s.ä.)? Interessant! Es war der Kollege vom Theaterressort, der ständig das Zitat von Blaise Pascal im Mund führte „Das ganze Unglück der Ralf (Felix Kramer, li.), Johannes (Ronald Zehrfeld, re.) und der Busstopp des Grauens Menschen rührt allein daher, dass sie nicht ruhig in einem Zimmer zu bleiben vermö- gen.“ Das sprach mich immer an, schließ- In der Warteschleife lich bin ich schon als junger Protojourna- list ungern vor die Türe gegangen. Wenn In der achtteiligen Serie „Warten auf ’n Bus“ reden Ronald Zehrfeld meine Eltern einen Ausflug zum Glienicker und Felix Kramer im Nirgendwo über alles und nichts See machen wollten, habe ich lieber den Onkel Tobias vom RIAS gehört. Und die Zwei Männer, ein Hund, eine Bushalte- gegrübelt wird. Auch für Becketts Godot- Reisen meines Vaters, durch die ich mehr- stelle irgendwo im Umland. Fertig ist das Szenario gibt es eine relativ neue Lesart, fach quer durch Europa geschleift wurde, Szenario für eine Art „Warten auf Godot“ nach der die Landstreicher Vladimir und hätte ich nicht gebraucht. Mir hat die Ge- in Brandenburg. Ralle (Felix Kramer), Han- Estragon vorm Faschismus geflüchtete gend „Westlich von Santa Fe“ gereicht nes (Ronald Zehrfeld) und Hund Maik französische Juden sein könnten, die auf (und dabei wusste ich damals noch nicht (Bozer), der aussieht „wie’n Uffahrunfall” ihren Résistance-Schleuser warten. -

CV Mr Jim Clancy

MR. JIM CLANCY CNN Jim Clancy brings the experience of more than 30 years covering the world to every newscast on CNN International. He didn't just read about the collapse of Communism, the fall of the Berlin Wall, the siege of Beirut, the Rwanda Genocide, or all of the Iraq wars. He was there. His career includes reporting on the events that have shaped history over the last quarter century. His interviews with international personalities reads like a "Who's Who" of our times. Currently, he is co-anchor of "Your World Today" with Zain Verjee, a weekday global news program that is simulcast on the CNN/U.S. network. Within this program, he gives viewers current affairs and the context to through the eyes of the day's top newsmakers and political analysts. While based at CNN's world headquarters in Atlanta, Clancy is also the moderator for "CNN Connects," the network's signature global panel discussion program, showcasing the world's top political and business leaders. "CNN Connects" and Jim Clancy have taken viewers to an unprecedented live session in Beijing examining China's rise on the world stage. In Davos, Switzerland, Arab Heads of State sat alongside an Israeli to hear all sides in the debate over Democracy. While in New Delhi, a vocal audience exchanged strong views with their own politicians and critics of outsourcing jobs from the U.S. to India. Additionally in 2004, Clancy hosted a discussion forum "Countdown to Handover: The Arab Pulse" in which Arab journalists hotly debated the prospects for peace and stability in Iraq. -

State of the News Media 2013” Chapters on Local Television News, Network News and Cable News Digital: As Mobile Grows Rapidly, the Pressures on News Intensify

Overview In 2012, a continued erosion of news reporting resources converged with growing opportunities for those in politics, government agencies, companies and others to take their messages directly to the public. Signs of the shrinking reporting power are documented throughout this year’s report. Estimates for newspaper newsroom cutbacks in 2012 put the industry down 30% since 2000 and below 40,000 full‐time professional employees for the first time since 1978. In local TV, our special content report reveals, sports, weather and traffic now account on average for 40% of the content produced on the newscasts studied while story lengths shrink. On CNN, the cable channel that has branded itself around deep reporting, produced story packages were cut nearly in half from 2007 to 2012. Across the three cable channels, coverage of live events and live reports during the day, which often require a crew and correspondent, fell 30% from 2007 to 2012 while interview segments, which tend to take fewer resources and can be scheduled in advance, were up 31%. Time magazine, the only major print news weekly left standing, cut roughly 5% of its staff in early 2013 as a part of broader company layoffs. And in African‐ American news media, the Chicago Defender has winnowed its editorial staff to just four while The Afro cut back the number of pages in its papers from 28‐32 in 2008 to around 16‐20 in 2012. A growing list of media outlets, such as Forbes magazine, use technology by a company called Narrative Science to produce content by way of algorithm, no human reporting necessary.