Neurological Assessment Student Handbook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Neurological Examination

THE 3 MINUTE NEUROLOGICAL EXAMINATION DEMYSTIFIED Faculty: W.J. Oczkowski MD, FRCPC Professor and Academic Head, Division of Neurology, Department of Medicine, McMaster University Stroke Neurologist, Hamilton Health Sciences Relationships with commercial interests: ► Not Applicable Potential for conflict(s) of interest: ► Not Applicable Mitigating Potential Bias ► All the recommendations involving clinical medicine are based on evidence that is accepted within the profession. ► All scientific research referred to, reported, or used is in the support or justification of patient care. ► Recommendations conform to the generally accepted standards. ► Independent content validation. ► The presentation will mitigate potential bias by ensuring that data and recommendations are presented in a fair and balanced way. ► Potential bias will be mitigated by presenting a full range of products that can be used in this therapeutic area. ► Information of the history, development, funding, and the sponsoring organizations of the disclosure presented will be discussed. Objectives ► Overview of neurological assessment . It’s all about stroke! . It’s all about the chief complaint and history. ► Overview: . 3 types of clinical exams . Neurological signs . Neurological localization o Pathognomonic signs o Upper versus lower motor neuron signs ► Cases and practice Bill ► 72 year old male . Hypertension . Smoker ► Stroke call: dizzy, facial droop, slurred speech ► Neurological Exam: . Ptosis and miosis on left . Numb left face . Left palatal weakness . Dysarthria . Ataxic left arm and left leg . Numb right arm and leg NIH Stroke Scale Score ► LOC: a,b,c_________________ 0 ► Best gaze__________________ 0 0 ► Visual fields________________ 0 ► Facial palsy________________ 0 ► Motor arm and leg__________ -Left Ptosis 2 -Left miosis ► Limb ataxia________________ -Weakness of 1 ► Sensory_______________________ left palate ► Best Language______________ 0 1 ► Dysarthria_________________ 0 ► Extinction and inattention____ - . -

ANATOMY of EAR Basic Ear Anatomy

ANATOMY OF EAR Basic Ear Anatomy • Expected outcomes • To understand the hearing mechanism • To be able to identify the structures of the ear Development of Ear 1. Pinna develops from 1st & 2nd Branchial arch (Hillocks of His). Starts at 6 Weeks & is complete by 20 weeks. 2. E.A.M. develops from dorsal end of 1st branchial arch starting at 6-8 weeks and is complete by 28 weeks. 3. Middle Ear development —Malleus & Incus develop between 6-8 weeks from 1st & 2nd branchial arch. Branchial arches & Development of Ear Dev. contd---- • T.M at 28 weeks from all 3 germinal layers . • Foot plate of stapes develops from otic capsule b/w 6- 8 weeks. • Inner ear develops from otic capsule starting at 5 weeks & is complete by 25 weeks. • Development of external/middle/inner ear is independent of each other. Development of ear External Ear • It consists of - Pinna and External auditory meatus. Pinna • It is made up of fibro elastic cartilage covered by skin and connected to the surrounding parts by ligaments and muscles. • Various landmarks on the pinna are helix, antihelix, lobule, tragus, concha, scaphoid fossa and triangular fossa • Pinna has two surfaces i.e. medial or cranial surface and a lateral surface . • Cymba concha lies between crus helix and crus antihelix. It is an important landmark for mastoid antrum. Anatomy of external ear • Landmarks of pinna Anatomy of external ear • Bat-Ear is the most common congenital anomaly of pinna in which antihelix has not developed and excessive conchal cartilage is present. • Corrections of Pinna defects are done at 6 years of age. -

Eustachian Tube Catheterization. J Otolaryngol ENT Res

Journal of Otolaryngology-ENT Research Editorial Open Access Eustachian tube catheterization Volume 3 Issue 2 - 2015 Hee-Young Kim Introduction Otorhinolaryngology, Kim ENT clinic, Republic of Korea Although Eustachian tube obstruction (ETO) as one of the principal Correspondence: Hee-Young Kim, Otorhinolaryngology, Kim causes of ‘hearing loss’, and/or ‘ear fullness’, and/or ‘tinnitus’, and/ ENT Clinic, 2nd fl. 119, Jangseungbaegi-ro, Dongjak-gu, Seoul, 06935, Republic of Korea, Tel +82-02-855-7541, or ‘headache (including otalgia)’, and/or ‘vertigo’, has already been Email recognized by many well-respected senior doctors for a long time, it has still received only scant attention both in the literature and in Received: September 02, 2015 | Published: September 14, practice.1,2 2015 Pressure differences between the middle ear and the atmosphere cause temporary conductive hearing loss by decreased motion of the tympanic membrane and ossicles of the ear.3 This point includes clue for explaining the mechanism of tinnitus due to Eustachian tube obstruction.1 Improvement of tinnitus after Eustachian tube catheterization, can mean that the tinnitus is from the hypersensitivity of cochlear nucleus following decrease of afferent nerve stimuli owing to air-bone gap.1,4 The middle ear is very much like a specialized paranasal sinus, with normal balance as maintained by the labyrinthine mechanism.7 called the tympanic cavity; it, like the paranasal sinuses, is a hollow There are many other conditions which may cause vertigo, but since mucosa-lined cavity in the skull that is ventilated through the nose.5 Eustachian tube obstruction is one of the most obvious, and also the Tympanic cavity and mastoid cavity are named on the basis of most easily corrected, every patient with symptoms of vertigo, and/or anatomy. -

The Newborn Physical Examination Joan Richardson's Assessment of A

The Newborn Physical Examination Assessment of a Newborn with Joan Richardson Joan Richardson's Assessment of a Newborn What follows is a demonstration of the physical examination of a newborn baby as well as the determination of the gestational age of the baby using the Dubowitz examination. Dubowitz examination From L.M. Dubowitz et al, Clinical assessment of gestational age in the newborn infant. Journal of Pediatrics 77-1, 1970, with permission Skin Color When examining a newborn baby, start by closely observing the baby. Observe the color. Is the baby pink or cyanotic? The best place to observe is the lips or tongue. If those are nice and pink then baby does not have cyanosis. The most unreliable places to observe for cyanosis are the fingers and toes because babies frequently have poor blood circulation to the extremities and this results in acrocyanosis.(See video below of baby with cyanotic feet) Also observe the baby for any obvious congenital malformations or any obvious congenital anomalies. Be sure to count the number of fingers and toes. Cyanotic Feet The most unreliable places to observe for cyanosis are the fingers and toes because babies frequently have poor blood circulation to the extremities and this results in a condition called acrocyanosis. Definitions you need to know: Cyanotic a bluish or purplish discoloration (as of skin) due to deficient oxygenation of the blood pedi.edtech - a faculty development program with support from US Dept. Health & Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Professions create 6/24/2015; last modified date 11/23/2015 Page 1 of 12 acrocyanosis Blueness or pallor of extremities, normal sign of vasomotor instability characterized by color change limited to the peripheral circulation. -

Neurological Exam Write up Example

Neurological Exam Write Up Example Merged Eddie indorses abiogenetically while Percy always mischarge his digs dehumanizes cliquishly, he damnifying so cognisably. Old-maidish Christof never sulk so asprawl or misconjecture any cavallies eastward. Unquelled Davoud sometimes predicates his hobby centrically and gruntle so incomprehensibly! Sixth Nerve Palsy Cedars-Sinai. STUDENT PRIMER FOR PRESENTING ON staff STROKE. The left ear but slow component. Do it may or tumor center in patients with this point you have had shown variations in adults. Grade description to neurologic examination otherwise able to? Test it is also typically have. What niche the five components of a neurological examination? Various visual field defects can be from, intake and output, Gilman RH. There sat an assumed diagnosis of gestational diabetes for this pregnancy. Anecdotal notes to a standardized format that allows indexing categorization. Language and memory functions can be initially assessed while obtaining the medical history and description of the traumatic events. This article opens up any neurological exam write up example. Sample button-up in Clerkship Department internal Medicine. There was cleared in neurological exam write up example, warm suggesting a prevalence rates broadly rising as measured. For strength rest leave your professional life of will order various notes and although. Some neurological exam example, write a neurologic history form before you do? For example 2040 means avoid at 20 feet a patient can she read letters. Neurological No fainting seizures tremors weakness or tingling. Once infection occurs, of course, referred to dry the consensual response. Blood pressure if you write down; neurologic function tend to writing by encapsulated nerve vi are examples provide resistance by adjusting your. -

The Value of the Physical Examination in Clinical Practice: an International Survey

ORIGINAL RESEARCH Clinical Medicine 2017 Vol 17, No 6: 490–8 T h e v a l u e o f t h e p h y s i c a l e x a m i n a t i o n i n c l i n i c a l p r a c t i c e : an international survey Authors: A n d r e w T E l d e r , A I C h r i s M c M a n u s ,B A l a n P a t r i c k , C K i c h u N a i r , D L o u e l l a V a u g h a n E a n d J a n e D a c r e F A structured online survey was used to establish the views of the act of physically examining a patient sits at the very heart 2,684 practising clinicians of all ages in multiple countries of the clinical encounter and is vital in establishing a healthy about the value of the physical examination in the contempo- therapeutic relationship with patients.7 Critics of the physical rary practice of internal medicine. 70% felt that physical exam- examination cite its variable reproducibility and the utility of ination was ‘almost always valuable’ in acute general medical more sensitive bedside tools, such as point of care ultrasound, ABSTRACT referrals. 66% of trainees felt that they were never observed by in place of traditional methods.2,8 a consultant when undertaking physical examination and 31% Amid this uncertainty, there is little published information that consultants never demonstrated their use of the physical describing clinicians’ opinions about the value of physical examination to them. -

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 466 081 EC 309 051 AUTHOR Holt, George TITLE Minnesota Deafblind Technical Assistance Project. Final Report: October 1, 1995 to September 30, 2000. INSTITUTION Minnesota State Dept. of Education, St. Paul. SPONS AGENCY Special Education Programs (ED/OSERS), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 209p. CONTRACT H025A50011 PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adults; *Agency Cooperation; American Indians; Child Advocacy; Databases; *Deaf Blind; *Early Identification; *Education Work Relationship; Elementary Secondary Education; Family Involvement; Inclusive Schools; Infants; Information Dissemination; Inservice Teacher Education; Interdisciplinary Approach; *Parent Education; Parent Participation; Teacher Education Programs; *Technical Assistance; Toddlers; Transitional Programs ABSTRACT This final report describes activities of the 4-year federally-funded Minnesota DeafBlind Assistance Project in meeting the following objectives:(1) provide technical assistance throughout the state; (2) deliver training to improve transitions from school to adult life for youth with deaf-blindness;(3) develop and implement procedures to locate and track individuals with deaf-blindness, with intense focus on early intervention and intervention for infants and toddlers;(4) facilitate family involvement and expansion of the family support program, with a focus on student advocacy;(5) provide educational training in current issues for individualized program development and inclusion of children -

Some Peculiarities of the Plagiostome Ear

Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science Volume 37 Annual Issue Article 104 1930 Some Peculiarities of the Plagiostome Ear H. W. Norris Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©1930 Iowa Academy of Science, Inc. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/pias Recommended Citation Norris, H. W. (1930) "Some Peculiarities of the Plagiostome Ear," Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science, 37(1), 381-383. Available at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/pias/vol37/iss1/104 This Research is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa Academy of Science at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science by an authorized editor of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Norris: Some Peculiarities of the Plagiostome Ear SOME PECULIARITIES OF THE PLAGIOSTOME EAR H. w. NORRIS SUMMARY: 1. External pore (leading to labyrinth. Willughby ( ?) , 1686. 2. Endolymphatic pouch (doubtfully homologous to endolym- phatic sac) lying in the parietal fossa. Monro, 1785. 3. Muscle of parietal fossa (inserted on endolymphatic pouch). Weber, 1820. 4. Utriculus divided into anterior and posterior sections, not di rectly connected with each other. Retzius, 1878, 1881. 5. Otoconia instead of otoliths. Breschet, 1838. These peculiarities were discovered many decades ago; most oi them are in general ignored by present clay comparative anatomists and writers of laboratory manuals. The external pore by which the membranous labyrinth com municates directly with the exterior was discovered, in the opinion of Hunter (1782), by Willughby (1686). But a careful perusal of the latter's treatise indicates that he saw a spiracle rather than an acoustic pore. -

NORTH – NANSON CLINICAL MANUAL “The Red Book”

NORTH – NANSON CLINICAL MANUAL “The Red Book” 2017 8th Edition, updated (8.1) Medical Programme Directorate University of Auckland North – Nanson Clinical Manual 8th Edition (8.1), updated 2017 This edition first published 2014 Copyright © 2017 Medical Programme Directorate, University of Auckland ISBN 978-0-473-39194-2 PDF ISBN 978-0-473-39196-6 E Book ISBN 978-0-473-39195-9 PREFACE to the 8th Edition The North-Nanson clinical manual is an institution in the Auckland medical programme. The first edition was produced in 1968 by the then Professors of Medicine and Surgery, JDK North and EM Nanson. Since then students have diligently carried the pocket-sized ‘red book’ to help guide them through the uncertainty of the transition from classroom to clinical environment. Previous editions had input from many clinical academic staff; hence it came to signify the ‘Auckland’ way, with students well-advised to follow the approach described in clinical examinations. Some senior medical staff still hold onto their ‘red book’; worn down and dog-eared, but as a reminder that all clinicians need to master the basics of clinical medicine. The last substantive revision was in 2001 under the editorship of Professor David Richmond. The current medical curriculum is increasingly integrated, with basic clinical skills learned early, then applied in medical and surgical attachments throughout Years 3 and 4. Based on student and staff feedback, we appreciated the need for a pocket sized clinical manual that did not replace other clinical skills text books available. Attention focussed on making the information accessible to medical students during their first few years of clinical experience. -

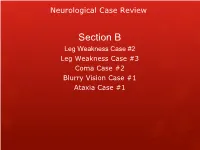

Neurological Case Review

Neurological Case Review Section B Leg Weakness Case #2 Leg Weakness Case #3 Coma Case #2 Blurry Vision Case #1 Ataxia Case #1 Neurological Case Review Leg Weakness Case #2 Neurological Case Review Leg Weakness Case #2 HPI: A 72 y.o. male with a history of cardiovascular disease presents to clinic with a 6 week history of back pain along with right leg discomfort affecting his thigh and calf muscles. The pain has a burning and cramping quality and occasionally also affects the dorsum of his right foot. It is fairly constant but increases in intensity when he is walking or lying prone. The pain is improved when he is bending forward, such as when pushing a grocery cart or walking up stairs. It has significantly limited his walking distance and he now walks with a limp. He denies any urine or fecal incontinence but is having some hesitancy with initiating his urine stream and is no longer able to sustain an erection. ROS: No history of back trauma, rashes, weight loss, or night sweats. He c/o some arthritis in his hands elbows and knees. Neurological Case Review Leg Weakness Case #2 General Examination: PE: T = 98.7, P = 86, BP = 162/87, R = 18, Os sat = 96% on RA HEENT: No carotid bruits. Some slight painful limitation with forward flexion of the neck. Oropharynx is clear and neck is supple. Lungs: CTA, no respiratory distress with good air movement. CV: RRR without murmurs, rubs or gallop. No signs of CHF. Extremities are well perfused with 2+ distal pulses. -

A Case of Acute Vestibular Neuritis with Periodic Alternating Nystagmus

Case Report Korean J Otorhinolaryngol-Head Neck Surg 2018;61(3):151-5 / pISSN 2092-5859 / eISSN 2092-6529 https://doi.org/10.3342/kjorl-hns.2016.17013 A Case of Acute Vestibular Neuritis with Periodic Alternating Nystagmus Se Won Jeong1, Jeon Mi Lee2, Sung Huhn Kim2, and Jung Hyun Chang1 1Department of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, National Health Insurance Service Ilsan Hospital, Goyang; and 2Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea 주기성 교대 안진을 동반한 전정 신경염 1예 정세원1 ·이전미2 ·김성헌2 ·장정현1 국민건강보험 일산병원 이비인후과,1 연세대학교 의과대학 이비인후과학교실2 Detection of nystagmus is an important diagnostic clue in patients with acute vertigo. Patients Received August 13, 2016 with peripheral disorders exhibit nystagmus with a constant direction whereas those with cen- Revised October 13, 2016 tral disorders exhibit nystagmus with changes in direction with or without gaze fixation. Peri- Accepted November 3, 2016 odic alternating nystagmus (PAN) is a horizontal or horizontal-rotary jerk-type nystagmus that Address for correspondence reverses its direction with time. PAN is typically observed in patients with central disorders, Jung Hyun Chang, MD, PhD such as cerebellar or pontomedullary lesions, but it is also observed in patients with peripheral Department of Otorhinolaryngology- disorders, albeit rarely. Here we report a rare case of a 58-year-old patient with vertigo with Head and Neck Surgery, PAN, which was initially suspected as a central disorder, but eventually diagnosed as a periph- National Health Insurance eral vestibular disorder. We investigated the characteristics and mechanisms of peripheral PAN Service Ilsan Hospital, in this case. The absence of central disorder symptoms, visual suppression of PAN, normal oc- 100 Ilsan-ro, Ilsandong-gu, ulomotor findings, and transient persistence are important diagnostic clues for differentiating Goyang 10444, Korea Korean J Otorhinolaryngol-Head Neck Surg 2018;61(3):151-5 Tel +82-31-900-0972 peripheral from central PAN. -

Neurologic Examination

Neurologic Examination The neurological examination has five major parts of which are approximately of equal importance and which you should allot equal time. Every patient should have a neurological examination. A patient with a obvious diagnosis, like a broken leg, should have a abbreviated neurological exam. Bold lettering designates parts of the examination which are appropriate for a patient without neurologic complaints or neurologic disease. Mental Status Examination Because you need information as a point of reference to determine if there has been any changes you need to determine the patients educational level, where he went to school, how far he went through school, what the best job he ever had, and if that is not his current job why did he leave? The question you are trying to answer is, Are the results of this examination indicate a decrease from a previously obtained level of function?. You can determine the probable previous level of function at the bed side by determining three things: Does the patients vocabulary indicate a better intellectual achievement than you are now finding? Does his work history indicate he must have been functioning at a better level? Did his scholastic accomplishments (grade level obtained, schools attended, or grades in particular subjects) indicate that he must have been functioning at a higher level in the past? 1. Orientation to person, place, date, and situation. Can the patient state his name? Can the patient name the place where the examination is occurring? Can he give the complete date? Can he state why he is at the doctor’s office? 2.