The University of Hull Fathering in the City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Extra Day Blackwood, Algernon

The Extra Day Blackwood, Algernon Published: 1915 Categorie(s): Fiction, Fantasy, Horror Source: http://www.gutenberg.org 1 About Blackwood: Although Blackwood wrote a number of horror stories, his most typical work seeks less to frighten than to induce a sense of awe. Good examples are the novels The Centaur, which cli- maxes with a traveller's sight of a herd of the mythical creatures; and Julius LeVallon and its sequel The Bright Mes- senger, which deal with reincarnation and the possibility of a new, mystical evolution in human consciousness. His best stor- ies, such as those collected in the book Incredible Adventures, are masterpieces of atmosphere, construction and suggestion. Born in Shooter's Hill (today part of south-east London, but then part of north-west Kent) and educated at Wellington Col- lege, Algernon Blackwood had a varied career, farming in Canada, operating a hotel, and working as a newspaper report- er in New York City. In his late thirties, Blackwood moved back to England and started to write horror stories. He was very successful, writing 10 books of short stories and appearing on both radio and television to tell them. He also wrote fourteen novels and a number of plays, most of which were produced but not published. He was an avid lover of nature, and many of his stories reflect this. Blackwood wrote an autobiography of his early years, Episodes Before Thirty (1923). There is an ex- tensive critical analysis of Blackwood's work in Jack Sullivan's book Elegant Nightmares: The English Ghost Story From Le Fanu to Blackwood (1978). -

“All Politicians Are Crooks and Liars”

Blur EXCLUSIVE Alex James on Cameron, Damon & the next album 2 MAY 2015 2 MAY Is protest music dead? Noel Gallagher Enter Shikari Savages “All politicians are Matt Bellamy crooks and liars” The Horrors HAVE THEIR SAY The GEORGE W BUSH W GEORGE Prodigy + Speedy Ortiz STILL STARTING FIRES A$AP Rocky Django Django “They misunderestimated me” David Byrne THE PAST, PRESENT & FUTURE OF MUSIC Palma Violets 2 MAY 2015 | £2.50 US$8.50 | ES€3.90 | CN$6.99 # "% # %$ % & "" " "$ % %"&# " # " %% " "& ### " "& "$# " " % & " " &# ! " % & "% % BAND LIST NEW MUSICAL EXPRESS | 2 MAY 2015 Anna B Savage 23 Matthew E White 51 A$AP Rocky 10 Mogwai 35 Best Coast 43 Muse 33 REGULARS The Big Moon 22 Naked 23 FEATURES Black Rebel Motorcycle Nicky Blitz 24 Club 17 Noel Gallagher 33 4 Blanck Mass 44 Oasis 13 SOUNDING OFF Blur 36 Paddy Hanna 25 6 26 Breeze 25 Palma Violets 34, 42 ON REPEAT The Prodigy Brian Wilson 43 Patrick Watson 43 Braintree’s baddest give us both The Britanys 24 Passion Pit 43 16 IN THE STUDIO Broadbay 23 Pink Teens 24 Radkey barrels on politics, heritage acts and Caribou 33 The Prodigy 26 the terrible state of modern dance Carl Barât & The Jackals 48 Radkey 16 17 ANATOMY music. Oh, and eco light bulbs… Chastity Belt 45 Refused 6, 13 Coneheads 23 Remi Kabaka 15 David Byrne 12 Ride 21 OF AN ALBUM De La Soul 7 Rihanna 6 Black Rebel Motorcycle Club 32 Protest music Django Django 15, 44 Rolo Tomassi 6 – ‘BRMC’ Drenge 33 Rozi Plain 24 On the eve of the general election, we Du Blonde 35 Run The Jewels 6 -

Everything Everything - a Fever Dream

Everything Everything - A Fever Dream Across three albums, immense acclaim and intense adoration, the sound of Everything Everything has remained a volatile beast; a musical bucking bronco, their albums maximalist, frenetic, art-pop juxtapositions of R’n’B and melancholia and Afrobeat, of synths, guitars, falsetto. Critics have written of the frenzy of it, of the sheer sublime sweet sensory overload of it all. Their fourth album, A Fever Dream, is a quite different prospect: a calibration of chaos and control, the result of a curious desire for consistency. As guitarist Alex Robertshaw puts it: “Our records have been many styles rubbing up against each other, and for the first time I wanted to make a record that was cohesive sonically.” Midway through touring 2015’s Get To Heaven, Robertshaw found himself listening increasingly to the kind of electronic music he had loved as a teenager — early Warp Records releases, Aphex Twin, Autechre, Boards of Canada, relishing “the atmosphere and the attitude” of them. “I wanted to go back to that thing that first made me excited about music,” he says. “We’ve spent a lot of time going into that R’n’B and hip hop world — for an indie band it was a bit of an untouchable thing, and it was really fun to do and I think we captured it at its best with Kemosabe and Arc. But once you start doing that you kind of separate yourself.” Contemplating a fourth album, and after an extensive run of touring, Robertshaw felt a need to reconnect with the sounds that had first thrilled him and inspired him to begin making music. -

Triple J Hottest 100 of the Decade Voting List: AZ Artists

triple j Hottest 100 of the Decade voting list: A-Z artists ARTIST SONG 360 Just Got Started {Ft. Pez} 360 Boys Like You {Ft. Gossling} 360 Killer 360 Throw It Away {Ft. Josh Pyke} 360 Child 360 Run Alone 360 Live It Up {Ft. Pez} 360 Price Of Fame {Ft. Gossling} #1 Dads So Soldier {Ft. Ainslie Wills} #1 Dads Two Weeks {triple j Like A Version 2015} 6LACK That Far A Day To Remember Right Back At It Again A Day To Remember Paranoia A Day To Remember Degenerates A$AP Ferg Shabba {Ft. A$AP Rocky} (2013) A$AP Rocky F**kin' Problems {Ft. Drake, 2 Chainz & Kendrick Lamar} A$AP Rocky L$D A$AP Rocky Everyday {Ft. Rod Stewart, Miguel & Mark Ronson} A$AP Rocky A$AP Forever {Ft. Moby/T.I./Kid Cudi} A$AP Rocky Babushka Boi A.B. Original January 26 {Ft. Dan Sultan} Dumb Things {Ft. Paul Kelly & Dan Sultan} {triple j Like A Version A.B. Original 2016} A.B. Original 2 Black 2 Strong Abbe May Karmageddon Abbe May Pony {triple j Like A Version 2013} Action Bronson Baby Blue {Ft. Chance The Rapper} Action Bronson, Mark Ronson & Dan Auerbach Standing In The Rain Active Child Hanging On Adele Rolling In The Deep (2010) Adrian Eagle A.O.K. Adrian Lux Teenage Crime Afrojack & Steve Aoki No Beef {Ft. Miss Palmer} Airling Wasted Pilots Alabama Shakes Hold On Alabama Shakes Hang Loose Alabama Shakes Don't Wanna Fight Alex Lahey You Don't Think You Like People Like Me Alex Lahey I Haven't Been Taking Care Of Myself Alex Lahey Every Day's The Weekend Alex Lahey Welcome To The Black Parade {triple j Like A Version 2019} Alex Lahey Don't Be So Hard On Yourself Alex The Astronaut Not Worth Hiding Alex The Astronaut Rockstar City triple j Hottest 100 of the Decade voting list: A-Z artists Alex the Astronaut Waste Of Time Alex the Astronaut Happy Song (Shed Mix) Alex Turner Feels Like We Only Go Backwards {triple j Like A Version 2014} Alexander Ebert Truth Ali Barter Girlie Bits Ali Barter Cigarette Alice Ivy Chasing Stars {Ft. -

Artist Song Title Disk

Artist Song Title Disk # A Perfect Circle Thanks for All the Fish Adele Skyfall Allman, Sheldon Crawl Out Through the Fallout Bird, Andrew Manifest Black Sabbath Electric Funeral War Pigs Boney M We Kill the World (don’t kill the world) Bowie, David Five Years Cave, Nick I’ll Love You Till the End of the World Cash, Johnny Five Feet High and Rising Clash, The London Calling Cohen, Leonard The Future Coldplay Spies Cranberries, The Zombie Credence Clearwater Revival Bad Moon Rising Crosby, Stills & Nash Wooden Ships Dan, Steely King of the World Dead Man’s Bones Lose Your Soul Depeche Mode Two Minute Warning Doors, The The End Draconian On Sunday They Will Kill the World Drake, Nick Pink Moon Dylan, Bob A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall Eilish, Billie All the Good Girls Go to Hell Everything Everything Radiant Foals I'm Done with the World Genesis Land of Confusion Grandmaster Flash The Message Guns and Roses Welcome to the Jungle Artist Song Title Disk # Imagine Dragons Radioactive Iron Maiden 2 Minutes to Midnight Lennon, John Imagine Louvin Brothers Great Atomic Power Marley, Bob Redemption Song McGuire, Barry Eve of Destruction Mingus, Charles Oh Lord Don’t Let Them Drop that Atomic Bomb on Me Minnelli, Liza Cabaret Mitchell, Joni Big Yellow Taxi Modern English I Melt With You Monae, Janelle Screwed Morrissey Everyday Is Like Sunday Mr. Lif Earthcrusher My Chemical Romance Na Na Na Neck Deep Happy Judgement Day Nena 99 Luftballons Newman, Randy Political Science Nine Inch Nails Survivalism Nirvana The Man Who Sold the World Pearl Jam Do the Evolution Police, The Invisible Sun Postal Service, The We Will Become Silhouettes Prince 1999 Sign o the Times Queens of the Stone Age The Sky is Fallin’ Radiohead Idioteque REM It’s the End of the World as We Know It Ritter, Josh Temptation of Adam Artist Song Title Disk # Rolling Stones, The Gimme Shelter Sleater Kinney Banned from the End of the World Smiths, The Ask Son Volt Down to the Wire Soundgarden Black Hole Sun St. -

Jon Hopkins, Alexis Taylor, Tom Misch & Everything Everything To

————————————————————————————————————— Jon Hopkins, Alexis Taylor, Tom Misch & Everything Everything to headline War Child’s ‘Safe & Sound’ gigs Three Shows on 25/26/27 November 2018 at O2 Shepherd’s Bush Empire Finale of the ‘Learn to Live’ Campaign Tickets go on general sale October 5 Tickets priced at £35 with VIP packages also available ———————————————————————————— WATCH THE #LEARNTOLIVE VIDEO HERE War Child UK is proud to announce that Everything Everything, Jon Hopkins and Tom Misch will be headlining three nights at O2 Shepherd’s Bush Empire on the 25th, 26th and 27th November. All proceeds will be going towards War Child UK as part of their Learn to Live Campaign and Ticketmaster will be donating a portion of the booking fee. The critically acclaimed acts will be in esteemed company, joining the likes of Take That, Wolf Alice, Coldplay, Jessie Ware, Muse, Tinie Tempah, Florence + the Machine, Craig David, Ed Sheeran, Blur, Rag ‘n’ Bone Man, The Killers, Calvin Harris and Mark Ronson as artists to have played War Child’s heralded shows. The three nights will be raising funds to ensure that children affected by conflict in areas including Iraq, Jordan and the Central African Republic, are given the support they need in schools to ensure they can recover from the psychological trauma of growing up in an area blighted by war and learn to live again. Jon Hopkins is an Ivor Novello Award nominee and two-time Mercury Prize shortlisted producer, who has collaborated with the likes of Massive Attack, Brian Eno, Coldplay and Herbie Hancock over a 20 year career. -

BIMM Manchester City and Accommodation Guide 2021/22

Manchester City and Accommodation Guide 2021/22 bimm.ac.uk Contents Welcome Welcome 3 As the College Principal for BIMM Institute Manchester, I Manchester is an incredible, multifaceted city with many know how important it is to choose the right place to study subtleties and scenes and our college reflects this in About Manchester 4 and start your education and career off on the right path. the student cohort and the great range of talent and My Manchester 10 experience represented in our teaching team. The music About BIMM Institute Manchester 14 Like many of you, I knew I wanted to my life to be in music scene here is one of the most renowned in the world and but it was only when my Mum suggested I think about for many of our staff – those of us who moved here from BIMM Institute Manchester Lecturers 16 studying it formally that this dream started to become a other parts of the UK or the world, or those that have been BIMM Institute Manchester Courses 18 reality. As I look back on this time, all of my friends were settled here for years – the city continues to enthral and Your City 22 going to college and university and I had my mind set on captivate us. doing English – because I was good at it. What I realised Music Resources 24 was that when choosing what you wanted to do for the rest Just like all the lecturers here at BIMM Institute Accommodation Guide 28 of your life, choosing something because you were good Manchester, I am industry active and continue to write, at it wasn’t necessarily the best option. -

Daily Iowan (Iowa City, Iowa), 1940-07-03

-,1940 . , :8 Baer Wins Fair, Wormer Play hoy Challenger Batten Ga IOWA: }'alr today and tomor leuio In Reavywelrbt Bout. Re., I row; BUChUy warmer g story on Page 4. &omonow. -, e ill JO~ L Iy 10 III 0 ,C i t y , • Morning Ne""paJJer n.a_........... fte .......... P_ FIVE CENTS IOWA CITY, IOWA WEDNESDAY, JULY 3,1940 VOLUME XL NUMBER 234 IIlk J, only at iunday I~ this h with. Strub .. ciating :r, Carl be in " ~~for 10 Was * * * * * * * * * * * * I *. * * . * *' *. * * *' * * * a City periO<\ Ion his ,97, he th the !. then Hungary .Seeks to Regain ·Province Strub, !:llh. +------- ---------------.----------.------~----~------------------~~--------------.--~-- Iowa 'e pre. Officials Exchange Bitter Tall{ Criticizes Hints RUSSIA AND TURKEY FOR JOINT CONTROL OF THIS :s ago, • Jews Shot Down and Beaten , Carl el· · C· At 'Subversive' " MTlI, Whil e M0 bI Izatlon ontInues; Acts in Schools In Bloody Waves of Disorder: I City; , vo sis. I Mrs. Germany Tries to Keep Peace MILWAUKEE, July 2 (AP)- King Carol Appeals to Hitler made William G. Carr, secretary of the I ------. ------ ler. educational policies commiSSion, e Elks Hilll'" Wall tR ScUlf>mcnt Between Two Counl1,je.'! Capital Blacked out ,First Tim. it, Amhn'an('es Washington, D. C., today criti I ber o{ To A~~u,'(' Protection of Oil Ficlfls cized "ill-Informed people" who Speed to Scenes of Rioting; - Which He Neelts hint at subversive activities and Soldiers at Frontiers agenci£3 in the public schools. -r BUDAPEST, July 2 (AP)-Hungarian and Rumanian In an address belore the Na- BUCHAREST, July 3 (Wednesday) (AP)--Anti-semitic officials exehangcd bittel' words over Transylvania tonight, ti onal Education association con rioting, with Jews shot down and beaten, swept in a bloody 'ch and Hungal'Y gave every s ign of determination to )'egain vention, Carr declared: wave overnight throughout old Rumania--harassed fl'Om that old province in one way or another. -

Mo Hausler - Engineer, Mixer, Producer

MO HAUSLER - ENGINEER, MIXER, PRODUCER Young Guns Livin’ On The Edge (forthcoming) Virgin EM Eng/Prod/Mixed Bleeding Heart Pigeons Forthcoming LP Virgin EMI Eng Incognito Amplified Soul (LP) Bluey Eng/Add- Music Prod/Mix Marina and The Diamonds FROOT (LP) Atlantic Eng Lake Malawi Forthcoming EP Lake Co-Prod/Mix Malawi Josh Record Pillars (LP) Virgin EMI Eng Shy Nature Lie Back (single) Kissability Add-Eng/Mix Gabrielle Aplin English Rain (live bonus tracks for LP) Parlophon Eng e Gareth Malone Voices: The Classical (EP) Decca Eng The Brand New Heavies Turn The Music Up (Forward LP) HeavyTone Mix Records Incognito Transatlantic RPM (LP) Bluey Eng/Mix Music Akimbo (BNH and JK Forthcoming LP Eng/Mix members) Robyn Sherwell Forthcoming LP Eng Nick Mulvey Fever To Form EP Fiction Eng Leon Ware Various Eng Rita Ora & K Koke Live session Roc Nation Eng The Irrepressibles New World (OST) Citizens! Recording session for advert Kitsune Eng Everything Everything Arc (LP) Sony Eng Mario Biondi Sun (LP) Sony Eng/Mix Gianna Nannini Inno (LP) Sony Eng Everything Everything Cough Cough (single) Sony Eng Mario Biondi Shine On (single) Sony Eng/Mix Gianna Nannini El Fine Del Mondo Sony Eng Bat For Lashes Horses of the Sun Parlophon Eng e Incognito Surreal (LP) Dome Eng/Mix Morning Parade Morning Parade (LP) Parlophon Eng e Bat For Lashes Strangelove Parlophon Eng e Animal Kingdom The Looking Away (LP) Q Prime Eng Gianna Nannini Io E Te Sony Eng Mika Elle Me Dit Universal Eng Dog Is Dead Hands Down Warner Eng To Kill A King My Crooked Saint (EP) Virgin -

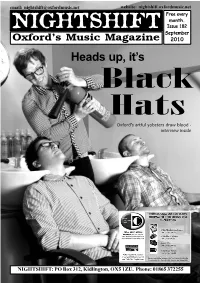

Issue 182.Pmd

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 182 September Oxford’s Music Magazine 2010 Heads up, it’s Black Hats Oxford’s artful yobsters draw blood - interview inside NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net TIM BEARDER HAS STEPPED Eynsham over the weekend of 4th- DOWN AS CO-HOST OF BBC 5th September after being re- RADIO OXFORD arranged from the end of July. The INTRODUCING. The presenter two-day event is headlined by who, along with Dave Gilyeat, was Newport’s rap crew Goldie responsible for establishing the Lookin’ Chain, alongside dedicated local music show on Borderville, Charly Coombes & BBC Oxford and helped pioneer The New Breed, Inflatable Buddha, the BBC’s Introducing programme, The Mighty Redox and more, while encouraging new music across the there are a wide range of dance UK. tents hosted by the likes of Having fronted the show since Bossaphonik, Xpression 2005, Tim celebrated five years on Recordings, Dat Sound, Field air in March with the release of Frequency and ZZBing. This ‘Round The Bends’, a tribute to year’s Arcane is dedicated to Radiohead’s classic ‘The Bends’ by former organiser and local graffiti up and coming Oxford bands. He artist Dan Lewis, aka Halfcut Art, was instrumental in championing who died in an accident in June. All OX4 returns for a second outing on Saturday 9th October. The event, a the likes of Little Fish, A Silent profits from the event will go to celebration of east Oxford’s music heritage, is organised by Truck. -

E2 EP Announce

! FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE UK’S EVERYTHING EVERYTHING TO RELEASE COUGH COUGH EP US DEBUT DUE OUT FEBRUARY 5th VIA JULIAN CASABLANCAS’ CULT RECORDS AND KEMOSABE RECORDS BAND TO HEADLINE SHOWS IN LOS ANGELES AND NEW YORK CITY THIS MARCH HERALDED NEW ALBUM DEBUTS AT NUMBER 5 ON THE UK ALBUM CHART LOS ANGELES, CA – JANUARY 23, 2013 - Everything Everything – Jonathan Higgs (singer/guitarist/keyboardist), Jeremy Pritchard (bass/keyboard), Alex Robertshaw (guitar), Michael Spearman (drums) – will release their long-awaited US debut EP, Cough Cough, on February 5th via Julian Casablancas’ Cult Records and Kemosabe Records. Said Julian Casablancas, "I’m honored to be associated with such a talented, mind bending, modern band." The EP will feature four songs – “Cough Cough”, “Kemosabe”, “Undrowned” and “Torso of the Week” – from their "perfectly concise, moving and visceral" (Pitchfork) new album, Arc, which will be released in the United States later this year; “MY KZ UR BF” from their debut album, Man Alive; and a remix of “Cough Cough.” Arc was recently released in the United Kingdom and debuted at Number 5 on the album chart. “’Cough Cough’ is about the power of money and the desire to get away from it. It's also about waking up and seeing the world as an unfair place and then slipping back under the spell of greed,” said Higgs. “It's about having no money, and wanting more money, and wanting nothing to do with money at all.” The title track “Cough Cough” is an instantly addictive and anthemic song showcasing many of the musical elements the band is known for, from the pounding drums to group vocals and Higgs’ signature falsetto. -

Mein Krautrocksampler

Krautrocksampler Interviews, Artikel und anderes extrahiert aus dem Internet und aufbereitet von Heinrich Unkenfuß Nur zum internen Gebrauch und zu wissenschaftlichen und Unterrichtszwecken. Hamburg, 13. 11. 2010 Inhaltsverzeichnis Ein Augen- und Ohrenflug zum letzten Himmel - Die Deutsche Rockszene um 1969 (von Marco Neumaier) 4 The German Invasion (by Mark Jenkins) 7 Krautrock (by Chris Parkin) 10 Rock In Deutschland - Gerhard Augustin Interview 12 An Interview With Julian Cope 17 Krautrock: The Music That Never Was 22 German Rock (SPIEGEL 1970) 25 Popmusik: Sp¨ates Wirtschaftswunder (SPIEGEL 1974) 27 Neger vom Dienst (SPIEGEL 1975) 29 Trance-Musik: Schamanen am Synthesizer (SPIEGEL 1975) 31 Zirpt lustig (SPIEGEL 1970) 34 Prinzip der Freude (SPIEGEL 1973) 36 The Mythos of Rolf-Ulrich Kaiser (1943-??) 38 Exhibitionisten an die Front (SPIEGEL 1969) 42 Communing With Chaos (by Edwin Pouncey) 44 Amon Du¨ul¨ II - Yeti Talks to Yogi 50 We Can Be Heroes (Amon Du¨ul¨ II) 57 Interview with John Weinzierl 60 Dave Anderson - The Bass-Odyssey Files 69 1 Kraut-Rock (Interview mit Chris Karrer) 74 Interview mit Tangerine Dream (1975) 77 Interview with Klaus Schulze 79 “I try to bring order into the chaos.” Klaus D. Mueller Interview 91 Die wahre Geschichte des Krautrock 96 Faust: Clear 102 The Sound of the Eighties 104 Faust and Foremost: Interview with Uwe Nettelbeck 107 Having a Smashing Time 110 Interview with Jochen Irmler 115 After The Deluge - Interview with Jean-Herv´eP´eron 117 Faust: Kings of the Stone Age 126 Faust - 30 Jahre Musik zwischen Bohrmaschine und Orgel 134 Hans Joachim Irmler: ‘Wir wollten die Hippies mal richtig erschrecken“’ 140 ” Can: They Have Ways of Making You Listen 145 An Interview With Holger Czukay (by Richie Unterberger) 151 An Interview With Holger Czukay (by Jason Gross) 155 D.A.M.O.