When Being No. 1 Is Not Enough

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Notice

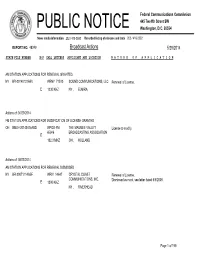

PUBLIC NOTICE Federal Communications Commission News Media Information 202 / 418-0500 445 12th St., S.W. Internet: http://www.fcc.gov Washington, D.C. 20554 TTY: 1-888-835-5322 Report Number: 15804 Date of Report: 04/07/2021 Wireless Telecommunications Bureau Site-By-Site Action Below is a listing of applications that have been acted upon by the Commission. AA - Aviation Auxiliary Group File Number Action Date Call Sign Applicant Name Purpose Action 0009476044 04/02/2021 WQNX569 District of Columbia, Government of RO G AF - Aeronautical and Fixed File Number Action Date Call Sign Applicant Name Purpose Action 0009474089 03/30/2021 KWV2 Chevron USA Inc. CA G 0009474092 03/30/2021 WKC8 Chevron USA Inc. CA G 0009474093 03/30/2021 WPA4 Chevron USA Inc. CA G 0009474094 03/30/2021 WRA6 Chevron USA Inc. CA G 0009474095 03/30/2021 WZO6 Chevron USA Inc. CA G 0009474096 03/30/2021 WPTJ670 Chevron USA Inc. CA G 0009474116 03/30/2021 KRG4 Chevron USA Inc. CA G 0009474117 03/30/2021 WRB7 Chevron USA Inc. CA G 0009474120 03/30/2021 KXJ9 Chevron USA Inc. CA G 0009474123 03/30/2021 WRD8 Chevron USA Inc. CA G 0009474124 03/30/2021 WRE2 Chevron USA Inc. CA G 0009474127 03/30/2021 WXK6 Chevron USA Inc. CA G Page 1 AF - Aeronautical and Fixed File Number Action Date Call Sign Applicant Name Purpose Action 0009438626 04/02/2021 WQNK617 TRINITY COUNTY AIRPORTS RO G AR - Aviation Radionavigation File Number Action Date Call Sign Applicant Name Purpose Action 0009423100 03/31/2021 WRMF509 State of MN MnDOT Aeronautics NE G AS - Aural Studio Transmitter Link File Number Action Date Call Sign Applicant Name Purpose Action 0009477270 04/01/2021 WLP823 BROOKE COMMUNICATIONS, INC. -

A Strategic Guide for the City-Wide Response to and Recovery from Major Emergencies and Disasters

OFFICE of EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT - BASIC PLAN Albuquerque, New Mexico A STRATEGIC GUIDE FOR THE CITY-WIDE RESPONSE TO AND RECOVERY FROM MAJOR EMERGENCIES AND DISASTERS Martin J. Chávez, Mayor CITY OF ALBUQUERQUE ALL HAZARDS EMERGENCY OPERATIONS PLAN VOLUME 2 - ANNEXES DECEMBER 2005 PREPARED BY: THE CITY OF ALBUQUERQUE OFFICE OF EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT OFFICE of EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT - BASIC PLAN ALBUQUERQUE EMERGENCY OPERATIONS PLAN VOLUME 2 - ANNEXES Table of Contents Annex # Page Annex 1 Direction and Control A-1-1 thru A-1-12 Annex 2 Communications, Warning & Emergency Alert A-2-1 thru A-2-15 Annex 3 Alert & Notification A-3-1 thru A-3-6 Annex 4 Law Enforcement A-4-1 thru A-4-24 Annex 5 Fire and Rescue A-5-1 thru A-5-22 Annex 6 Health and Medical A-6-1 thru A-6-55 Annex 7 Critical Infrastructure A-7-1 thru A-7-11 Annex 8 Damage Assessment and Reporting A-8-1 thru A-8-13 Annex 9 Transportation A-9-1 thru A-9-6 Annex 10 Evacuation A-10-1 thru A-10-20 Annex 11 Logistics and Resources A-11-1 thru A-11-3 Annex 12 Education, Training, Testing and Exercises A-12-1 thru A-12-11 ALBUQUERQUE EMERGENCY OPERATIONS PLAN ANNEX 1 DIRECTION & CONTROL Primary Responsibility: Mayor of the City of Albuquerque/President of the City Council Chief Administrative Officer Chief Public Safety Officer Secondary Responsibility: All City Departments and Divisions Lead Agencies Emergency Management Fire Police Environmental Health Secondary Agencies Water Authority Municipal Development Legal Finance & Administrative Services Solid Waste Management Transit Senior Affairs Family & Community Services I. -

Agenda Regular Meeting City of Fairfield Planning Commission

AGENDA REGULAR MEETING CITY OF FAIRFIELD PLANNING COMMISSION VIA TELECONFERENCE FEBRUARY 10, 2021 JOIN MEETING VIA ZOOM LINK: 6:00 P.M. https://fairfieldca.zoom.us/j/97065607498?pwd=a1dnaVY2UzFINU4xaU5sS0FET09qZz09 PASSWORD: 66781819 Consistent with the Governor's Executive Order N-29-20 regarding public meetings during the COVID-19 emergency, Planning Commissioners may attend the meeting telephonically. Members of the public can observe the meeting on Comcast Cable Channel 26, ATT U-Verse 99, and web-streamed live http://www.fairfield.ca.gov/live, or at www.youtube.com/user/FFCATV/live. Members of the public may join the meeting via Zoom with the following link: https://fairfieldca.zoom.us/j/97065607498?pwd=a1dnaVY2UzFINU4xaU5sS0FET09qZz09 Password: 66781819 I. ROLL CALL II. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE III. INFORMATION ON PROVIDING PUBLIC COMMENTS Persons wishing to address the Planning Commission on subjects not on the agenda but within the jurisdiction of the Planning Commission provided that NO action may be taken on off-agenda items except as authorized by law. Off-agenda items from the public will be taken under consideration without discussion by the Commission and may be referred to staff. Comments will be accepted via Zoom or by email at [email protected]. Identify your name, the item you wish to comment on, and the date of the meeting. All comments received by email prior to the start of an item will be read aloud for up to three minutes. For adjudicative public hearing items, e-mailed comments will be accepted and read aloud for up to three/four minutes if received prior to the close of the public hearing PUBLIC COMMENT INSTRUCTIONS: When joining via Zoom, please use the “raise your hand” feature or press *9 on your phone to request to speak. -

Insideradio.Com

800.275.2840 MORE NEWS» insideradio.com THE MOST TRUSTED NEWS IN RADIO FRIDAY, OCTOBER 30, 2015 Elvis Duran: Hosts ‘More Important Than Ever.’ Streaming music services may have stiffened competition for radio’s share of ear but they’ve done nothing to diminish the role of on-air personalities. In fact, the opposite is true, according to Elvis Duran, radio’s most listened-to top 40 morning man, in an exclusive interview with Inside Radio. “It makes us radio hosts more important than ever,” says the “Z100” WHTZ, New York-based Duran of the syndicated “Elvis Duran and the Morning Show.” “Even though we have a whole world of music at our fingertips, having a human connect you to the music is still very important. We are the people who add the human connectivity to music and musicians.” Duran also extols digital platforms in the discussion, praising them for giving personalities more ways to connect with the audience. Snapchat is a favorite among his show’s cast members. “It really is as close to the radio experience as you can get with any social media right now,” he says. “It is personable and it is of the moment; it is on and then 24 hours later it is gone. There is a sense of urgency to it.” Duran, who will be inducted into the National Radio Hall of Fame Nov. 5, explains how he and his cohosts work product mentions into the show so seamlessly. “A lot of times, we go to the sales department and say, ‘I have found myself using this product more and more. -

Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 48249 Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL GRANTED NY BR-20140131ABV WENY 71510 SOUND COMMUNICATIONS, LLC Renewal of License. E 1230 KHZ NY ,ELMIRA Actions of: 04/29/2014 FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR MODIFICATION OF LICENSE GRANTED OH BMLH-20140415ABD WPOS-FM THE MAUMEE VALLEY License to modify. 65946 BROADCASTING ASSOCIATION E 102.3 MHZ OH , HOLLAND Actions of: 05/23/2014 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL DISMISSED NY BR-20071114ABF WRIV 14647 CRYSTAL COAST Renewal of License. COMMUNICATIONS, INC. Dismissed as moot, see letter dated 5/5/2008. E 1390 KHZ NY , RIVERHEAD Page 1 of 199 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 48249 Broadcast Actions 5/29/2014 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 05/23/2014 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE GRANTED NY BAL-20140212AEC WGGO 9409 PEMBROOK PINES, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License From: PEMBROOK PINES, INC. E 1590 KHZ NY , SALAMANCA To: SOUND COMMUNICATIONS, LLC Form 314 NY BAL-20140212AEE WOEN 19708 PEMBROOK PINES, INC. -

He KMBC-ÍM Radio TEAM

l\NUARY 3, 1955 35c PER COPY stu. esen 3o.loe -qv TTaMxg4i431 BItOADi S SSaeb: iiSZ£ (009'I0) 01 Ff : t?t /?I 9b£S IIJUY.a¡:, SUUl.; l: Ii-i od 301 :1 uoTloas steTaa Rae.zgtZ IS-SN AlTs.aantur: aTe AVSí1 T E IdEC. 211111 111111ip. he KMBC-ÍM Radio TEAM IN THIS ISSUE: St `7i ,ytLICOTNE OSE YN in the 'Mont Network Plans AICNISON ` MAISHAIS N CITY ive -Film Innovation .TOrEKA KANSAS Heart of Americ ENE. SEDALIA. Page 27 S CLINEON WARSAW EMROEIA RUTILE KMBC of Kansas City serves 83 coun- 'eer -Wine Air Time ties in western Missouri and eastern. Kansas. Four counties (Jackson and surveyed by NARTB Clay In Missouri, Johnson and Wyan- dotte in Kansas) comprise the greater Kansas City metropolitan trading Page 28 Half- millivolt area, ranked 15th nationally in retail sales. A bonus to KMBC, KFRM, serv- daytime ing the state of Kansas, puts your selling message into the high -income contours homes of Kansas, sixth richest agri- Jdio's Impact Cited cultural state. New Presentation Whether you judge radio effectiveness by coverage pattern, Page 30 audience rating or actual cash register results, you'll find that FREE & the Team leads the parade in every category. PETERS, ñtvC. Two Major Probes \Exclusive National It pays to go first -class when you go into the great Heart of Face New Senate Representatives America market. Get with the KMBC -KFRM Radio Team Page 44 and get real pulling power! See your Free & Peters Colonel for choice availabilities. st SATURE SECTION The KMBC - KFRM Radio TEAM -1 in the ;Begins on Page 35 of KANSAS fir the STATE CITY of KANSAS Heart of America Basic CBS Radio DON DAVIS Vice President JOHN SCHILLING Vice President and General Manager GEORGE HIGGINS Year Vice President and Sally Manager EWSWEEKLY Ir and for tels s )F RADIO AND TV KMBC -TV, the BIG TOP TV JIj,i, Station in the Heart of America sú,\.rw. -

Who Pays Soundexchange: Q1 - Q3 2017

Payments received through 09/30/2017 Who Pays SoundExchange: Q1 - Q3 2017 Entity Name License Type ACTIVAIRE.COM BES AMBIANCERADIO.COM BES AURA MULTIMEDIA CORPORATION BES CLOUDCOVERMUSIC.COM BES COROHEALTH.COM BES CUSTOMCHANNELS.NET (BES) BES DMX MUSIC BES ELEVATEDMUSICSERVICES.COM BES GRAYV.COM BES INSTOREAUDIONETWORK.COM BES IT'S NEVER 2 LATE BES JUKEBOXY BES MANAGEDMEDIA.COM BES MEDIATRENDS.BIZ BES MIXHITS.COM BES MTI Digital Inc - MTIDIGITAL.BIZ BES MUSIC CHOICE BES MUSIC MAESTRO BES MUZAK.COM BES PRIVATE LABEL RADIO BES RFC MEDIA - BES BES RISE RADIO BES ROCKBOT, INC. BES SIRIUS XM RADIO, INC BES SOUND-MACHINE.COM BES STARTLE INTERNATIONAL INC. BES Stingray Business BES Stingray Music USA BES STORESTREAMS.COM BES STUDIOSTREAM.COM BES TARGET MEDIA CENTRAL INC BES Thales InFlyt Experience BES UMIXMEDIA.COM BES SIRIUS XM RADIO, INC CABSAT Stingray Music USA CABSAT MUSIC CHOICE PES MUZAK.COM PES SIRIUS XM RADIO, INC SDARS 181.FM Webcasting 3ABNRADIO (Christian Music) Webcasting 3ABNRADIO (Religious) Webcasting 8TRACKS.COM Webcasting 903 NETWORK RADIO Webcasting A-1 COMMUNICATIONS Webcasting ABERCROMBIE.COM Webcasting ABUNDANT RADIO Webcasting ACAVILLE.COM Webcasting *SoundExchange accepts and distributes payments without confirming eligibility or compliance under Sections 112 or 114 of the Copyright Act, and it does not waive the rights of artists or copyright owners that receive such payments. Payments received through 09/30/2017 ACCURADIO.COM Webcasting ACRN.COM Webcasting AD ASTRA RADIO Webcasting ADAMS RADIO GROUP Webcasting ADDICTEDTORADIO.COM Webcasting ADORATION Webcasting AGM BAKERSFIELD Webcasting AGM CALIFORNIA - SAN LUIS OBISPO Webcasting AGM NEVADA, LLC Webcasting AGM SANTA MARIA, L.P. -

UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2009 OR o TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File Number 001-09553 CBS CORPORATION (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) DELAWARE 04-2949533 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification Number) 51 W. 52nd Street New York, NY 10019 (212) 975-4321 (Address, including zip code, and telephone number, including area code, of registrant's principal executive offices) Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Name of Each Exchange on Title of Each Class Which Registered Class A Common Stock, $0.001 par value New York Stock Exchange Class B Common Stock, $0.001 par value New York Stock Exchange 7.625% Senior Debentures due 2016 American Stock Exchange 7.25% Senior Notes due 2051 New York Stock Exchange 6.75% Senior Notes due 2056 New York Stock Exchange Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None (Title of Class) Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer (as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act of 1933). Yes ☒ No o Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. -

The Clear Picture on Clear Channel Communications, Inc.: a Corporate Profile

Cornell University ILR School DigitalCommons@ILR Articles and Chapters ILR Collection 1-28-2004 The Clear Picture on Clear Channel Communications, Inc.: A Corporate Profile Maria C. Figueroa Cornell University, [email protected] Damone Richardson Cornell University, [email protected] Pam Whitefield Cornell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/articles Part of the Advertising and Promotion Management Commons, Arts Management Commons, and the Unions Commons Thank you for downloading an article from DigitalCommons@ILR. Support this valuable resource today! This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the ILR Collection at DigitalCommons@ILR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles and Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@ILR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. If you have a disability and are having trouble accessing information on this website or need materials in an alternate format, contact [email protected] for assistance. The Clear Picture on Clear Channel Communications, Inc.: A Corporate Profile Abstract [Excerpt] This research was commissioned by the American Federation of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) with the expressed purpose of assisting the organization and its affiliate unions – which represent some 500,000 media and related workers – in understanding, more fully, the changes taking place in the arts and entertainment industry. Specifically, this report examines the impact that Clear Channel Communications, with its dominant positions in radio, live entertainment and outdoor advertising, has had on the industry in general, and workers in particular. Keywords AFL-CIO, media, worker, arts, entertainment industry, advertising, organization, union, marketplace, deregulation, federal regulators Disciplines Advertising and Promotion Management | Arts Management | Unions Comments Suggested Citation Figueroa, M. -

Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage

Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage Aaron Joseph Johnson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Aaron Joseph Johnson All rights reserved ABSTRACT Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage Aaron Joseph Johnson This dissertation is a study of jazz on American radio. The dissertation's meta-subjects are mediation, classification, and patronage in the presentation of music via distribution channels capable of reaching widespread audiences. The dissertation also addresses questions of race in the representation of jazz on radio. A central claim of the dissertation is that a given direction in jazz radio programming reflects the ideological, aesthetic, and political imperatives of a given broadcasting entity. I further argue that this ideological deployment of jazz can appear as conservative or progressive programming philosophies, and that these tendencies reflect discursive struggles over the identity of jazz. The first chapter, "Jazz on Noncommercial Radio," describes in some detail the current (circa 2013) taxonomy of American jazz radio. The remaining chapters are case studies of different aspects of jazz radio in the United States. Chapter 2, "Jazz is on the Left End of the Dial," presents considerable detail to the way the music is positioned on specific noncommercial stations. Chapter 3, "Duke Ellington and Radio," uses Ellington's multifaceted radio career (1925-1953) as radio bandleader, radio celebrity, and celebrity DJ to examine the medium's shifting relationship with jazz and black American creative ambition. -

The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy

Mount Rushmore: The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy Brian Asher Rosenwald Wynnewood, PA Master of Arts, University of Virginia, 2009 Bachelor of Arts, University of Pennsylvania, 2006 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Virginia August, 2015 !1 © Copyright 2015 by Brian Asher Rosenwald All Rights Reserved August 2015 !2 Acknowledgements I am deeply indebted to the many people without whom this project would not have been possible. First, a huge thank you to the more than two hundred and twenty five people from the radio and political worlds who graciously took time from their busy schedules to answer my questions. Some of them put up with repeated follow ups and nagging emails as I tried to develop an understanding of the business and its political implications. They allowed me to keep most things on the record, and provided me with an understanding that simply would not have been possible without their participation. When I began this project, I never imagined that I would interview anywhere near this many people, but now, almost five years later, I cannot imagine the project without the information gleaned from these invaluable interviews. I have been fortunate enough to receive fellowships from the Fox Leadership Program at the University of Pennsylvania and the Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia, which made it far easier to complete this dissertation. I am grateful to be a part of the Fox family, both because of the great work that the program does, but also because of the terrific people who work at Fox. -

A Critical Ideological Analysis of Mass Mediated Language

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-2006 Democracy, Hegemony, and Consent: A Critical Ideological Analysis of Mass Mediated Language Michael Alan Glassco Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Glassco, Michael Alan, "Democracy, Hegemony, and Consent: A Critical Ideological Analysis of Mass Mediated Language" (2006). Master's Theses. 4187. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/4187 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEMOCRACY, HEGEMONY, AND CONSENT: A CRITICAL IDEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF MASS MEDIA TED LANGUAGE by Michael Alan Glassco A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College in partial fulfillment'of the requirements for the Degreeof Master of Arts School of Communication WesternMichigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 2006 © 2006 Michael Alan Glassco· DEMOCRACY,HEGEMONY, AND CONSENT: A CRITICAL IDEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF MASS MEDIATED LANGUAGE Michael Alan Glassco, M.A. WesternMichigan University, 2006 Accepting and incorporating mediated political discourse into our everyday lives without conscious attention to the language used perpetuates the underlying ideological assumptions of power guiding such discourse. The consequences of such overreaching power are manifestin the public sphere as a hegemonic system in which freemarket capitalism is portrayed as democratic and necessaryto serve the needs of the public. This thesis focusesspecifically on two versions of the Society of ProfessionalJournalist Codes of Ethics 1987 and 1996, thought to influencethe output of news organizations.